The 9th of November was not a day of national commemoration in England, where I grew up. We had to

“Remember, remember the 5th of November, gunpowder, treason and plot…”

The Gunpowder Plot Conspirators, unknown engraver, ca. 1605-1606

This was the date on which Guy Fawkes, a Catholic renegade, dramatically failed to blow up London’s House of Lords. This cultural memory has been faithfully preserved for over 400 years. However, the 9th of November never went unremarked in our household. It was always referred to in German with a shudder: “Kristallnacht,” a name and concept for which no English equivalent exists.

Moving to Germany in 2001, I was surprised to discover that the 9th of November was indeed a day when the organized pogroms against Jews in Germany in 1938 were discussed in the media and commemorative events were held. → continue reading

Photograph from World War II. The sellers priced it at 3000 euros.

The financial crisis of 2007 had an impact both on the countries of Western and Eastern Europe. The złoty may still glitter but it has long since ceased to be the “golden coin” Polish currency was originally named for. Unemployment and stagnant economic growth, rising real estate prices and declining purchasing power have put the brake on Poland’s economic recovery. The Netherlands has likewise been in recession for years. Declining competitiveness, private debts, state-subsidized home ownership, the low retirement age and the expensive health care system have fed uncertainty and repeatedly paved the path to success for the Freedom Party of the populist xenophobe Geert Wilders.

The Polish letter of offer as we received it.

This downward spiral in state treasury and personal funds led a couple of Polish resp. Dutch wheeler-dealers to scrape the barrel for a bilateral business model. Crafty Dariusz Woźniok and his fly-by-night Dutch client somehow managed to get their hands on infantrymen’s photos from the Second World War—whether as thieves or buyers it is impossible to say. Maybe they were embittered by the fact that no share in the tidy profits made from material goods ever came their way, from the export of Polish geese, strawberries, potatoes and beetroot, for example, or of Dutch cheese and tulips. Maybe they hatched their business plan in an Amsterdam coffee shop and had simply smoked one hash pipe too many. Whatever the case, they figured: “It was a sure bet that snapshots of ghettos and so-called ‘Jewish actions’ in early 1940s Poland could be sold off as ‘Holocaust-ware’ to Jewish Museums—so why not make the most of an historic windfall?” → continue reading

Dealing Creatively with Ethnic Classifications

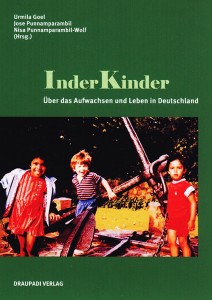

Book cover

© Draupadi Verlag

Tomorrow at the Academy of the Jewish Museum Berlin, Urmila Goel and Nisa Punnamparambil-Wolf will introduce the book they edited, InderKinder – Über das Aufwachsen und Leben in Deutschland (Indian-Children: on Growing Up and Living in Germany, published by Drapaudi Verlag). It’s the third in a series of events on “New German Stories” where, with the aid of individual biographies, we examine Germany’s historical and current status as an immigration society. On this occasion we’ll focus on the children of immigrants from India, who gained public awareness for the first time during the “Green Card” campaign of 2000.

Prior to the reading and discussion tomorrow, we asked the two editors, Nisa Punnamparambil-Wolf and Urmila Goel, three questions:

What made you choose this title?

We’re referring with this title to the marginalizing “Kinder statt Inder” (children instead of Indians) campaign of the year 2000. The wordplay of InderKinder (Indian-children) is meant ironically: it was important to us to find a creative way to deal with these attributions. With the book, we want to show the varied ways that people who grew up and live in Germany handle the classification of being a child of Indian immigrants.

The book consists of two parts, autobiographical stories and essays. How would you explain your concept?

→ continue reading