A Guest Entry by Rudij Bergmann

Accompanying our current exhibition, “No Compromises! The Art of Boris Lurie,” Rudij Bergmann’s film about the artist will premiere on 21 March 2016 (additional information available on our event calendar). In this guest entry, the filmmaker tells us how this very personal documentary came about.

The artist’s longing for Europe was palpable from the moment I first saw him in the dim light of an apartment hallway on New York’s 66th Street. Stepping into his home studio, confronted by this breathtaking collage of memory, it was immediately clear to me that Boris Lurie hadn’t fully left the concentration camps he survived with his father – at least mentally.

It was October 1996. A film for the television magazine BERGMANNsART, which I’m for all intents and purposes responsible for, was the reason to rush to see Lurie in New York. (The film, in German and with age restriction, is available on YouTube.)

It was the beginning of a long friendship. → continue reading

Film Historian Claudia Dillmann on the Artur Brauner Film Collection in Our Library

The German film producer and Shoah survivor Artur Brauner has kindly donated to our Museum twenty-one films on the subject of the Shoah and the Nazi era—you’ll find the complete list on our website. Today, the Museum acknowledges our great appreciation of this gift with a special event in the presence of Artur Brauner and his family.

Claudia Dillmann

Photo: Deutsches Filminstitut/Uwe Dettmar

Prior to the event we interviewed film historian Claudia Dillmann about Artur Brauner and the appeal of his film productions, in particular for a Jewish Museum. Ms. Dillmann is Director of the German Film Institute in Frankfurt Main and a renowned expert on Artur Brauner, and also initiated the online resource www.filmportal.de. She talked to us about Brauner’s interest in the victims of Nazi crimes, the balancing acts it has called for, his veneration of Romy Schneider, and the German public’s tastes.

Mirjam Bitter, Blog Editor: Ms. Dillman, in your opinion, how representative is our Artur Brauner Film Collection of Mr. Brauner’s entire production list?

Claudia Dillmann: The films that Artur Brauner has donated to the Jewish Museum are indeed representative since they constitute a pivot of his career—one very dear to his heart—namely an abiding commitment to exposing the Holocaust, not least because forty-nine of his own relatives also lost their lives then. He sees these films as his personal “legacy,” one he has been forging since the start of his career. They are dedicated to victims of the Nazi regime and constitute a cycle that in his view is still not complete. In them, he has continually explored new facets of persecution under the Nazi terror and of the traumata he lived through himself. → continue reading

Program Director Cilly Kugelmann on the Exhibition “NO COMPROMISES! The Art of Boris Lurie”

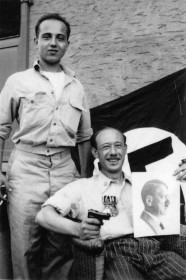

“As this image of Lurie with his brother-in-law Dino Russi from 1946 shows, the NO!art artists, in reclaiming the swastika symbol, robbed it of its symbolic value.” (Cilly Kugelmann)

Boris Lurie Art Foundation, New York

Our major retrospective dedicated to Boris Lurie opens 26 February 2016 (for more information see www.jmberlin.de/lurie/en). Blog editor Mirjam Bitter spoke with Cilly Kugelmann about the artist, his provocative work, and the possible impact today of the taboos that he broke throughout his career.

Mirjam Bitter: What is your view of Boris Lurie? What sort of a guy was he? What distinguished him as an artist?

Cilly Kugelmann: The man and the artist Boris Lurie was shaped by his experience of persecution and concentration camps under the Nazi regime. And yet, unlike other artists who faced similar experiences, I feel he cannot be described as a “Holocaust artist.” With the exception of some early drawings from 1946 and a few paintings from the late 1940s, he neither chronicled these events nor sought to interpret the Holocaust artistically in his work.

Then what role did the Holocaust play in Lurie’s work? → continue reading