The Tragic Fate of Shmuel Dancyger Z. L.

The family at the grave of Shmuel Dancyger; Jewish Museum Berlin, gift of Morris Dancyger

During a visit to my hometown of Calgary Alberta, Canada in the summer of 2014, I had the opportunity to meet with Morris and Ann Dancyger, both child survivors of the Holocaust. Morris Dancyger was one of the very few children to have been liberated by the Russians at Auschwitz on 27 January 1945. In the iconic footage of the children displaying their tattooed arms, four year old Morris is in the center of the picture. Ann Dancyger and her mother had miraculously survived an execution in 1942 near the town of Ratno where she was born, and spent nearly three years thereafter in hiding. After a nearly two year trek to Germany following the end of the war, she was able to come to Calgary where relatives lived. I had not known the Dancygers while growing up in the city, and although I had much later read about the tragic fate of Morris Dancyger’s father Shmuel, I was completely unaware that his wife and children had settled in Calgary. → continue reading

An Early April Fool’s Joke from the Year 1931

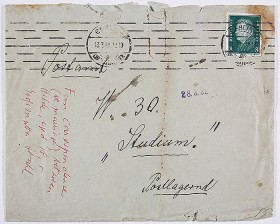

Envelope posted 13 March 1931; Jewish Museum Berlin, Gift of Margaret Littman and Susan Wolkowicz, the daughters of Hilde Gabriel née Salomonis

Sometimes figuring out how to classify a document correctly according to its historical context can depend on just one tiny, even seemingly unrelated detail. I was reminded of this again while working on the inventory of a recent donation to our archive. With more than 3,000 documents, photographs, and objects, the Gabriel-Salomonis family collection includes among other things an extensive correspondence. This consists of letters, postcards, and even telegrams, and as I sorted through these items, I came across an exchange of four letters from the early spring of 1931. Two were handwritten: composed and signed, quite legibly, by the then 72-year-old, Berlin resident Ernestine Stahl (1858–1933). The author of the other two type-written letters was at first uncertain, not least because his signature was missing. Ernestine Stahl addressed him in her replies only as “Sir” and “Dear Sir.”

I was able to solve this little riddle, however, by looking at an envelope that turned up elsewhere of the bundle of papers but appeared to belong to this brief exchange. → continue reading

Film Historian Claudia Dillmann on the Artur Brauner Film Collection in Our Library

The German film producer and Shoah survivor Artur Brauner has kindly donated to our Museum twenty-one films on the subject of the Shoah and the Nazi era—you’ll find the complete list on our website. Today, the Museum acknowledges our great appreciation of this gift with a special event in the presence of Artur Brauner and his family.

Claudia Dillmann

Photo: Deutsches Filminstitut/Uwe Dettmar

Prior to the event we interviewed film historian Claudia Dillmann about Artur Brauner and the appeal of his film productions, in particular for a Jewish Museum. Ms. Dillmann is Director of the German Film Institute in Frankfurt Main and a renowned expert on Artur Brauner, and also initiated the online resource www.filmportal.de. She talked to us about Brauner’s interest in the victims of Nazi crimes, the balancing acts it has called for, his veneration of Romy Schneider, and the German public’s tastes.

Mirjam Bitter, Blog Editor: Ms. Dillman, in your opinion, how representative is our Artur Brauner Film Collection of Mr. Brauner’s entire production list?

Claudia Dillmann: The films that Artur Brauner has donated to the Jewish Museum are indeed representative since they constitute a pivot of his career—one very dear to his heart—namely an abiding commitment to exposing the Holocaust, not least because forty-nine of his own relatives also lost their lives then. He sees these films as his personal “legacy,” one he has been forging since the start of his career. They are dedicated to victims of the Nazi regime and constitute a cycle that in his view is still not complete. In them, he has continually explored new facets of persecution under the Nazi terror and of the traumata he lived through himself. → continue reading