The exclusion of Jewish children from public schools under the NS-dictatorship

What an apparently innocuous postcard from 23 November 1938 reveals

Dominic Strieder

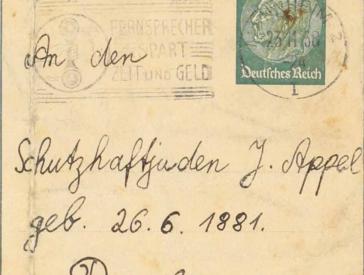

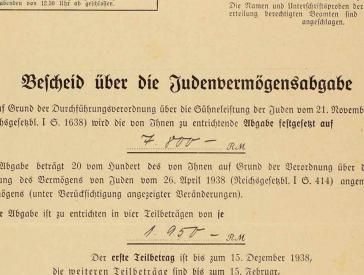

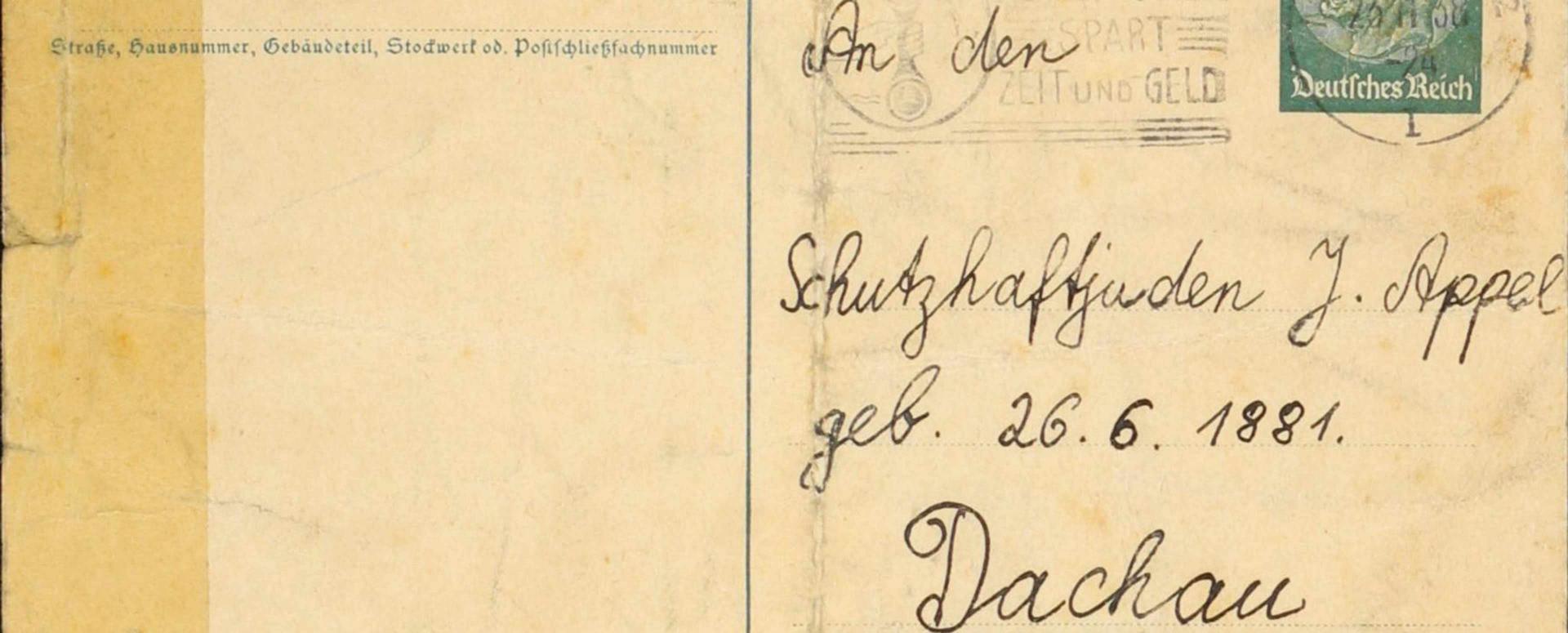

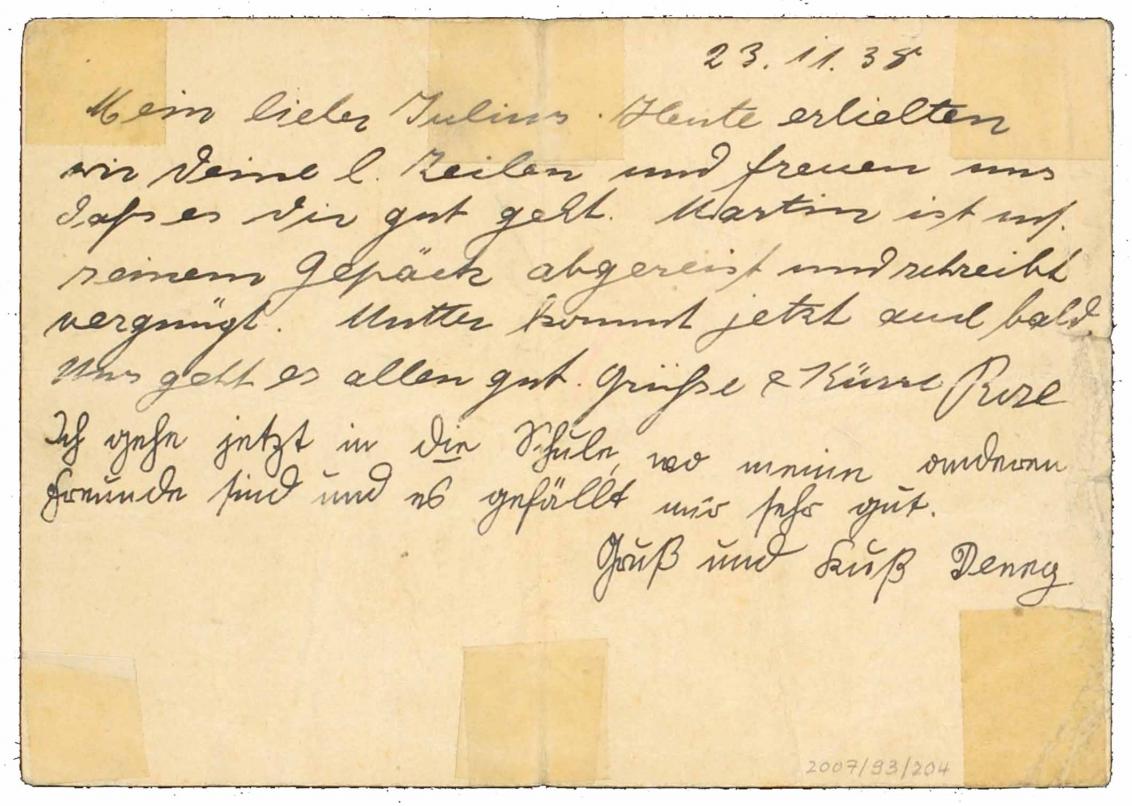

In the regular archive workshops that we conduct with students in grades 8–13 (and sometimes also with university students), a working group will often focus on the situation of Jewish students during the Nazi period. They research the subject using primary documents and photographs taken from our collection. One of the key documents frequently studied in this context is an apparently innocuous postcard from November 23, 1938, bearing a 6-penny-stamp issued by the 3rd Reich which shows an image of the deceased President von Hindenburg. One can distinguish on the postcard the hand of two different writers, an adult and a child.

Back side of a postcard from Rosa und Rudolf (here signing Denny) Appel to Julius Appel, Mannheim, November 23, 1938; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2007/93/204, gift of Rudy Appel

Translated transcript of the text on the postcard

23.11.1938

My dear Julius. Today we received

your l[ovely] lines and are glad

that you are well. Martin has departed

with his suitcase and writes

cheerfully. Mother is coming soon now, too.

We are all well. Greetings and kisses Rose

I am going to school now, where my other

friends all are, and I like it a lot.

A greeting and a kiss Denny

The child’s handwriting belongs to Rudolf Appel, who writes to his father Julius: “I am going to school now, where my other friends all are, and I like it a lot.” The text and picture appear at first sight harmless enough. If we examine the context in which the postcard was written more closely, however, its poignancy becomes apparent. For “Denny” is writing on 23 November 1938 to the “Jew in Protective Custody Julius Appel,” one of 30,000 Jewish men deported and imprisoned in Nazi concentration camps following the November pogroms.

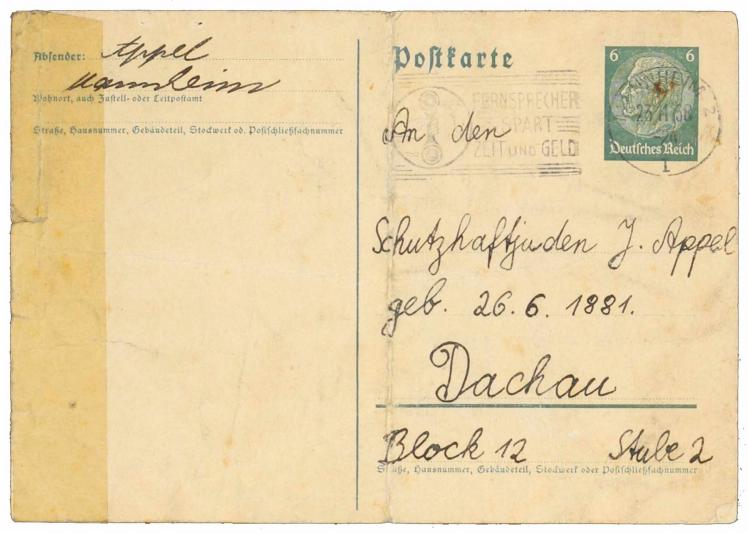

Front side of a postcard to Julius Appel, Mannheim, November 23, 1938; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2007/93/204, gift of Rudy Appel

Translated transcript of the text on the postcard

Sender: Appel

Place of residence and local or principal post office: Mannheim

Street, House Number, Building, Floor or Mailbox Number: -

Postcard

To the

Protective custody Jew J. Appel

born 26.6.1881

Dachau

Street, House Number, Building, Floor or Mailbox Number: Block 12 Room 2

Rudolf was 13 years old at the time. He had started school under the Weimar Republic. Following primary school, he had attended the Karl-Friedrich Gymnasium in Mannheim. Why did he have to leave that school so suddenly in November 1938? And why was it so important for him to mention that all his friends were in the new school?

The restructuring of the school system

Following their seizure of power, the National Socialists drove Jewish students out of the public schools. The measures to affect this were introduced via the “Statute to combat the overcrowding of German Schools and Universities” promulgated on April 25, 1933. Under this law, the number of children of “non-Aryan” descent attending a school was capped at 5 percent. In the case of new enrollments, the percentage allowed was reduced to just 1.5 percent. This new regulation was promulgated at about the same time as the “Statute for the Regeneration of the Civil Service,” which likewise excluded Jewish teachers from the school system. At first, primary schools were excluded from the scope of the law. Moreover, the children of Jewish frontline soldiers from the First World War generally could attend all public schools, even if the quota of “non-Aryan” children in an educational institution was exceeded.

The exclusion of Jewish teachers and students from the public schools increased the demand for Jewish schools dramatically. Soon, the existing Jewish schools were filled to capacity and many new educational institutions had to be founded, both by the Jewish communities and by private educators.

These schools essentially had three tasks: first, they needed to provide children with a space in which they would be protected from anti-Semitic attacks. Secondly, they sought to cultivate a positive Jewish self-image through intensive study of Jewish history and culture. Thirdly – especially starting in 1938, and in particular through foreign language instruction – the children were to be prepared for emigration and a life outside Germany. The Chairman of the Jewish Community of Mannheim Max Grünewald summarized the school’s mission in 1936 as follows: "We hope that the school will provide calm and continuity to many parents, as well. They may now rest assured that their children can experience childhood and youth with unbroken spirits, within their own world and in the steady and festive rhythm of the Jewish year, but also that they will be acquiring at the same time the indispensible tools for their future." (Watzinger, Karl Otto: Geschichte der Juden in Mannheim 1650–1945, p. 64, to the book in our library catalog) In this way, many schools were able to develop into "islands of security" for children and young adults.

"Segregation of the races in the school system"

Following the November Pogroms, it was completely forbidden for Jewish students to attend public schools. On 15 November 1938, the Nazi state Ministry for Science and Education issued an order stating that "[a]fter the nefarious murder of Paris … it is unacceptable to expect that any German teacher provide instruction to Jewish schoolchildren. It should also be self-evident that it is intolerable for German schoolchildren to sit in a classroom shared with Jews." To be sure, the order continued, "the segregation of the races in the school system has already been affected to a large extent over the past several years ... nevertheless, there remains an oddment of Jewish children in German schools, who henceforth can no longer be permitted to attend school together with German boys and girls." (Amtsblatt des Reichsministeriums für Wissenschaft, Erziehung und Volksbildung und der Unterrichtsverwaltungen der Länder, vol. 4 (1938), p. 520, to the book in our library catalog) It was this order that compelled Rudolf Appel to leave the Gymnasium he was attending and switch to the Jewish School in Mannheim.

After November 1938

Rudolf did not stay there long, however. Even prior to the November Pogroms, the Appel family had made efforts towards emigration, since Julius Appel was no longer permitted to work as notary. It was only after 9 November, however, that the first family member was able to leave Germany, when eldest son Martin succeeded in immigrating to the USA via the Netherlands. After being released from the concentration camp, Julius also reached the USA in January 1939. While Rudolf and his mother Rosa managed to get out of Germany in 1939, they got caught in an odyssey of migration involving numerous stations in Belgium, the Netherlands and France. The family was not reunited until 1946, following the Allies’ victory over National Socialist Germany.

The schoolchildren who stayed behind

However, thousands of Jewish schoolchildren, together with their parents, did not have the good fortune, the opportunity, or the requisite pecuniary means to get out of Germany. Instead, they remained at the mercy of the Nazis. The Jewish schools, too, experienced increasing difficulty in operating after the outbreak of war. On the one hand, the body of teachers and students fluctuated wildly as a result of emigration, so that it was hard to maintain any semblance of a regular teaching schedule. On the other hand, the ever more repressive process of dispossession, aryanization, and exclusion from lucrative work, as well as the widespread practice of forced labor affecting those who remained in Germany made it more and more difficult for the Community schools or private schools reachable from urban centers to raise the funds they needed.

After the commencement of deportations to occupied territories in the East and the prohibition on emigration issued in connection therewith in the Fall of 1941, Jewish children were forbidden in June 1942 from attending any school whatsoever, and all Jewish schools were closed. At the same time, the children were forbidden to receive instruction from any “paid or unpaid” teachers. As a result, Jewish children were de facto exempted from the duty to attend school.

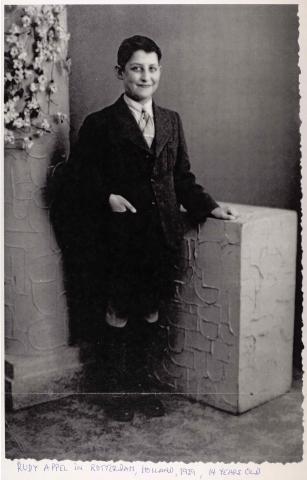

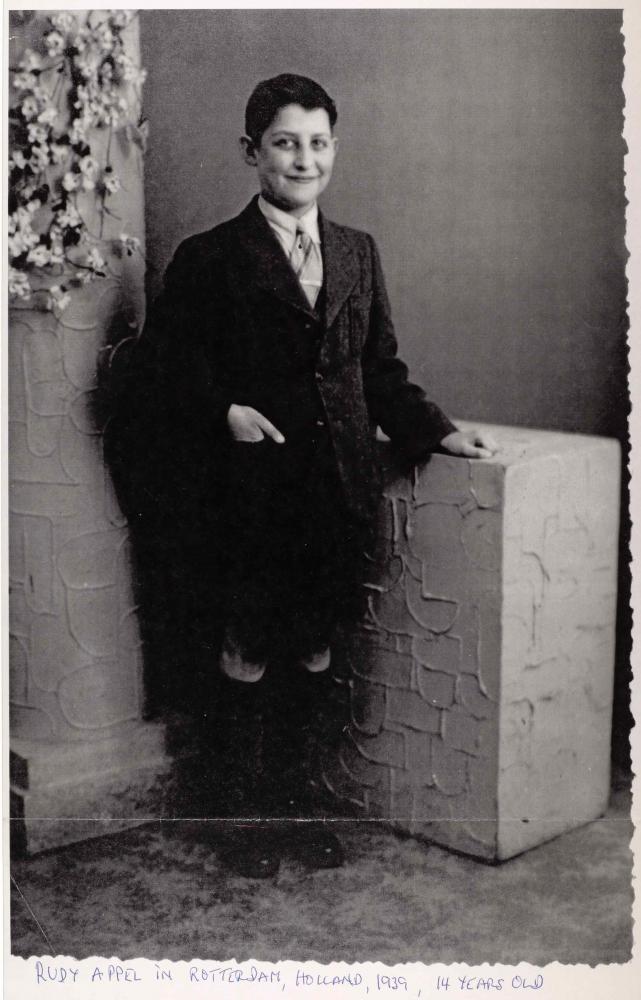

Rudolf Appel at age 14, Rotterdam, 1939; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2008/320/19, gift of Rudy Appel

Citation recommendation:

Dominic Strieder (2018), The exclusion of Jewish children from public schools under the NS-dictatorship. What an apparently innocuous postcard from 23 November 1938 reveals.

URL: www.jmberlin.de/en/node/5913

Online Features: The Background and Ramifications of 9 November 1938 (5)