“Travel Toward a Happy Future!”

The 1938/39 Kindertransporte in our Family Collections

Franziska Bogdanov

Nearly 18,000 children from Germany and the occupied territories (Austria and the Czech Republic) were saved from Nazi tyranny by the Kindertransporte. Over half of the children were taken to Great Britain. For all of these children, however, this meant being separated from their parents – sometimes for months, sometimes years, and often forever. The Jewish Museum archive contains documents from children who were brought to safety in this way. These documents often leave a deep impression of the children’s zest for life and curiosity, as well as their worries about the fate of those left behind and the fears and hardships of their parents; impressions of parting and loss.

An Arduous Separation

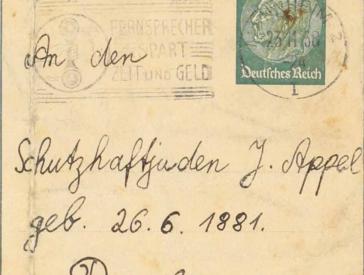

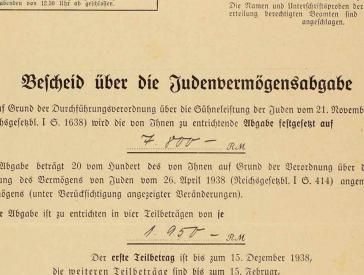

One of these children was Erika Freundlich from Hamburg. She was 16 years old when she traveled with a Kindertransport to England. Her father wrote about their farewell in a letter to his elder daughter:

“I still can’t quite imagine that Erika shouldn’t be here anymore. […] You cannot imagine the way the parents and children said farewell to each other. I saw three small children there, the youngest may have been 5 years old, her little hand holding her sister’s, who was maybe one or two years older. The littlest one refused to leave their mother. The entire scene of the emigrating children was wretched.”

Beate Rose’s number tag from the Kindertransport rescue mission; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2010/217/99, gift of Beatrice Steinberg. Further information on this object can be found in our online collections (in German). You can learn more about Beate Rose in an article written by archive staff member Franziska Bogdanov on the 75th anniversary of the first Kindertransport (read article).

Beate Rose’s number tag from the Kindertransport rescue mission; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2010/217/99, gift of Beatrice Steinberg. Further information on this object can be found in our online collections (in German). You can learn more about Beate Rose in an article written by archive staff member Franziska Bogdanov on the 75th anniversary of the first Kindertransport (read article).

“On Parting”

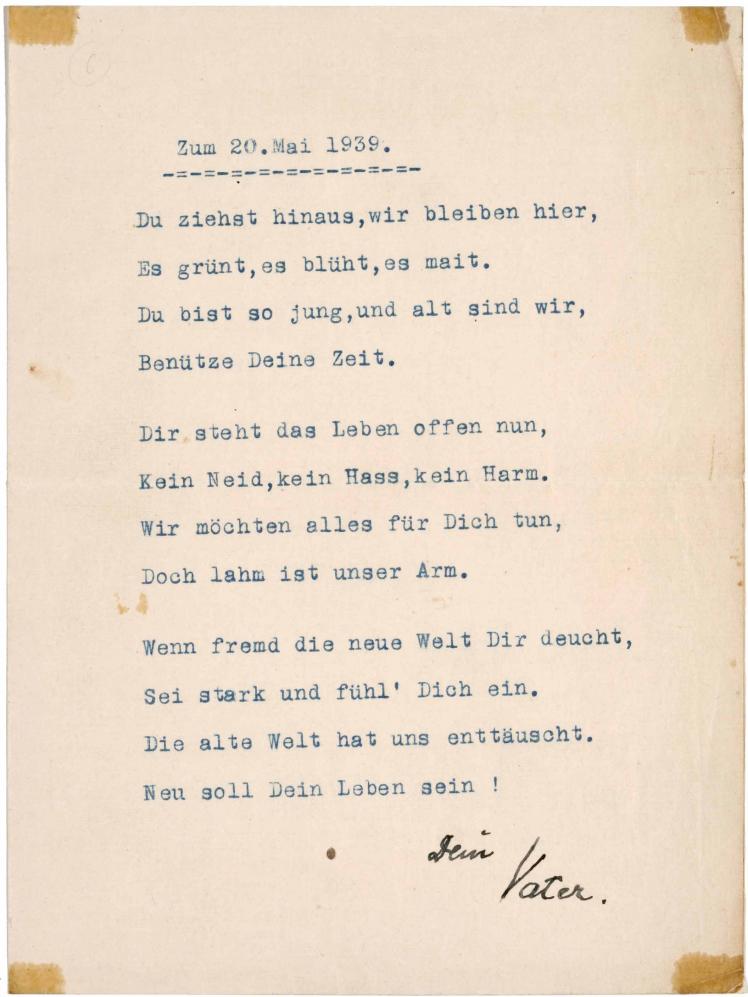

Poem by Max Heymann (1877–1944) for his daughter regarding her upcoming Kindertransport to England on 20 May 1939; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2000/95/6, gift of Frithjof and Eva Haas. Further information on this document can be found in our online collections (in German)

Translated transcript of the poem

For 20 May 1939You’re setting out, we’re staying home,

Seasons turn, flowers climb.

You’re so young, and we are old

Make use of your time.Your life is open and new,

No envy, no hate, no grief.

We want to do everything for you,

But our arms are weak.If the new world seems curious,

Be strong and try to puzzle through.

The old world disappointed us.

Your life will be new!Your father

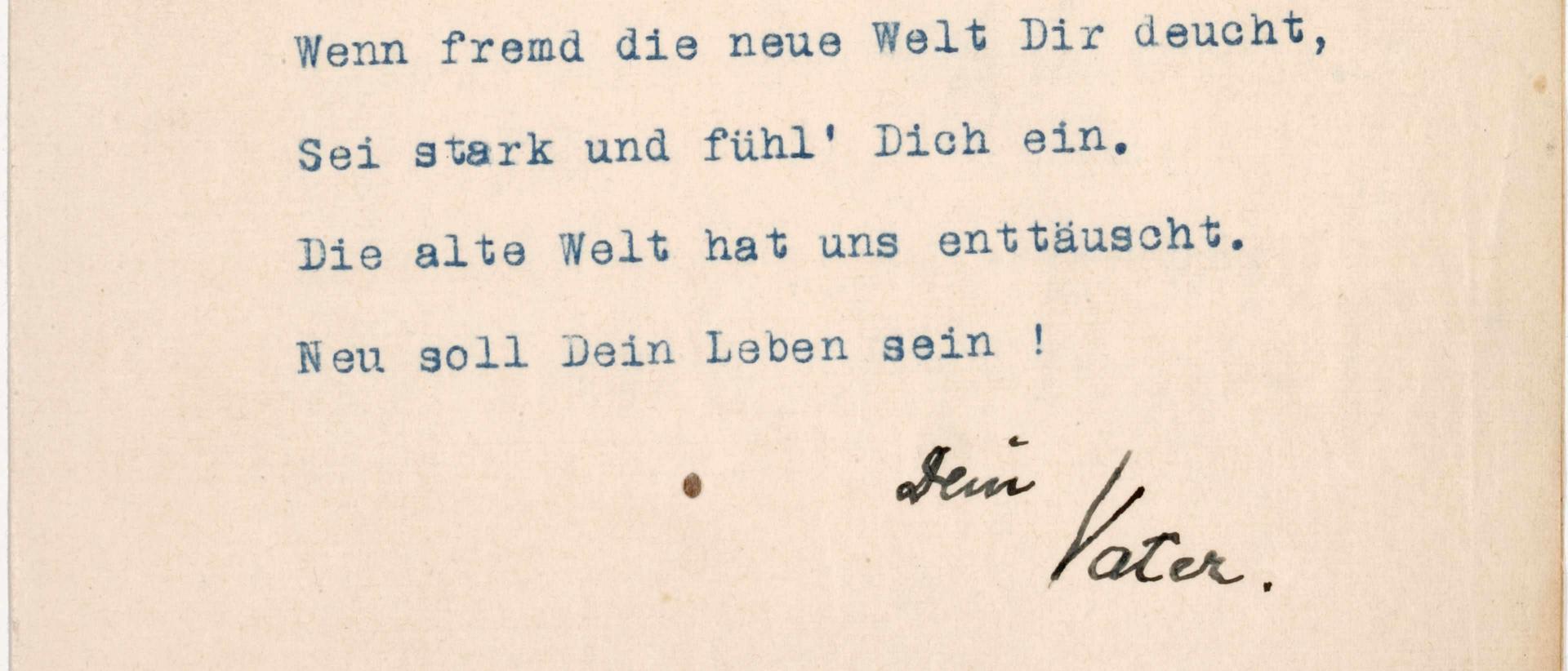

As painful as it was to let the children leave, it was often the only hope that at least they would have a secure future. Max Heymann from Berlin wrote a poem for his 14-year-old daughter Eva on the occasion of her departure on 20 May 1939. It ended with lines of encouragement: “If the new world seems curious, be strong and try to puzzle through. The old world disappointed us. Your life will be new!”

Eva Heyman would start a new life in England, but she would never see her father again. He died in the Theresienstadt ghetto in 1944.

The lucky ones followed

Alfred Dienemann of Berlin also fearfully awaited the separation from his 14 and 9-year-old children, Ursula and Wolfgang. In mid-December—he had just been released from the Sachsenhausen concentration camp—he wrote to his siblings in Palestine:

“We hope that we can send both children to schools in England in the coming weeks. Later they are supposed to go to the USA, to schools or elsewhere. The endless negotiations are still up in the air. Then we have ‘seen children off.’ I can’t bring myself to tell you the meaning that lies behind these words. At the same time, the struggle is for ourselves.”

A few months after their children were saved, Dienemann and his wife were able to follow them to England.

Brothers Kurt und Günter Treitel, aged 16 and 11, left Berlin in March 1939 with a farewell letter from their mother in their bag:

“My thoughts, my wishes, and my affections will forever follow and reach you. Travel toward a happy future, our blessing accompanies you!”

Hanna Lilly Treitel wrote these lines not knowing if she would ever see her sons again. At that point she didn’t know that she, her husband, and her younger daughter would be able to emigrate to England in July 1939. The oldest son, Kurt, who together with his brother had been living with an uncle for some months, had already begun to follow the advice of the refugee organization on how to adapt to British customs as quickly as possible. He wrote a postcard in English to his parents and sister for their arrival in Southampton: “Parents, dear Sis, A hearty welcome in England. Hope to see you soon” and signed with “Yours Kenneth (Kurt).”

…but luck was rare

Letters were generally the only way for parents and children to stay in contact. With the outbreak of war, for censorship reasons it was difficult for the children to continue writing in German. Letters often took weeks or months to arrive, and often they didn’t arrive at all, if the parents had been deported.

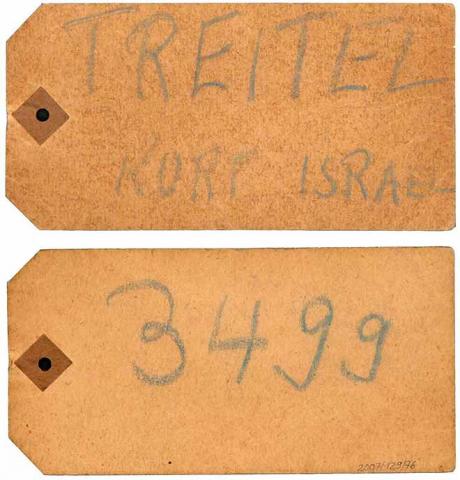

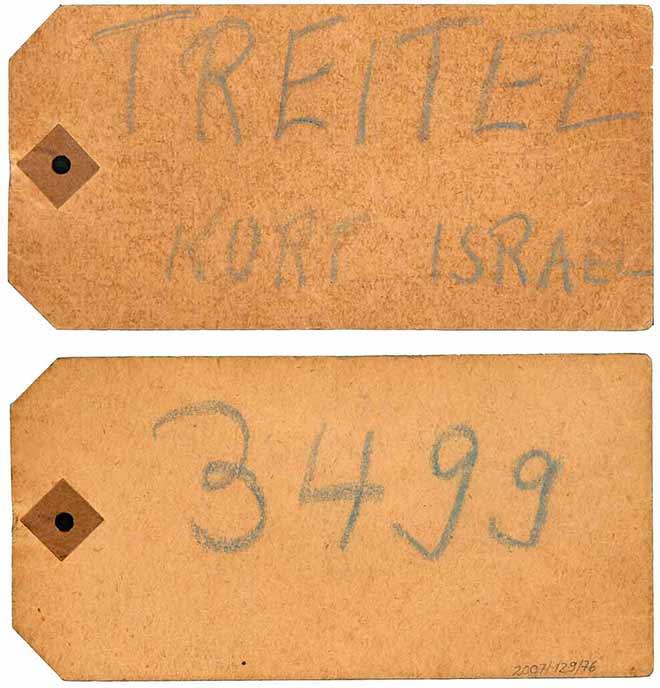

Kurt Treitel’s name tag with the mandatory addition “Israel”; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2007/129/76, gift of Kurt Treitel. Further information on this object can be found in our online collections (in German)

Kurt Treitel’s name tag with the mandatory addition “Israel”; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2007/129/76, gift of Kurt Treitel. Further information on this object can be found in our online collections (in German)

For siblings Stefan und Carola Prager from Berlin, who were 14 and 11 years old when they left Germany, the separation from their parents was permanent. On 26 October 1941, just before their deportation, their parents sent a final letter to Sweden. After their father, Wolfgang Prager, announced that they “would soon go on a big journey,”

he added:

“Never forget your parents, who always only wanted everything good for you. Stay true to each other and support each other in times of crisis.”

Their mother Ruth wrote below:

“I hardly know what I should say to you because my heart is so full, and words are so small and say so little. I have always only hoped for a reunion with you, but likely we are now standing before a twist of fate.”

Joy and crisis

Herta Silzer of Vienna emigrated to England in February 1939. When the 11-year-old reached British soil, the fear of the preceding days and weeks was outweighed by the euphoria of the new. She wrote to her parents:

“Today I arrived at 2pm in London. […] It is fantastic. […] The city makes an overwhelming impression.”

Herta went to relatives in Glasgow and sent her parents letters and postcards from there nearly every day. She was very worried about her parents, and on 23 March 1939, she asked:

“Since your last letter I haven’t gotten any mail for you, hopefully I will get some soon. – How are you? Are you healthy? Isn’t there any news? I would be so interested to know what’s going on.”

Eventually, her parents had the opportunity to emigrate to Cuba on the passenger ship St. Louis, but they weren’t allowed to disembark there and had to return to Europe. Herta’s parents were, however, allowed to enter England. On 21 June 1939 they arrived there and finally saw their daughter again, and in fall they were able to emigrate together to the United States.

This teddy bear accompanied Herta Silzer during the Kindertransport from Vienna to Great Britain; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2013/4/0, gift of Herta Weinstein née Silzer. Further information on this object can be found in our online collections (in German)

This teddy bear accompanied Herta Silzer during the Kindertransport from Vienna to Great Britain; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2013/4/0, gift of Herta Weinstein née Silzer. Further information on this object can be found in our online collections (in German)

A new life

Annemarie Fleck from Danzig went to England with a Kindertransport at age 13. She lived with a foster family and wrote to her parents on 28 October 1939:

“I’m so happy that you’re healthy. Everything here is just as usual, you can’t tell there’s a war. Everyone has enough and I eat a ghastly amount. I help out a lot more at home, and except for cooking I can do almost everything. My foster-mama says she doesn’t know how she’ll get along without me.”

For Annemarie a new life began in England. In her weekly letters to her parents, who were often traveling for months at a time following their emigration to Shanghai in 1941, she wrote extensively of her daily life, experiences with friends, her first love, and school. In Shanghai, her parents were distraught. It seemed to them that their daughter had become estranged to them, to which Annemarie answered in English on 20 July 1940:

“I’m sorry […], that you seem to know me so little as to have any doubt about my feelings.”

And she assured them that she only wrote about these “little, stupid events”

to stay optimistic and to enjoy life, which she also hoped her parents would do, since “Who knows what may happen in the Future?”

Annemarie Fleck (top, 2nd from left) on her arrival in England, 5 May 1939; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2018/125/35, gift of Diane Shavelson

Today, only a few of the now elderly “Kinder” are still alive. That makes it all the more important that we preserve their stories in the archive, so that they are not forgotten.

Citation recommendation:

Franziska Bogdanov (2018), “Travel Toward a Happy Future!”. The 1938/39 Kindertransporte in our Family Collections.

URL: www.jmberlin.de/en/node/5935

Online Features: The Background and Ramifications of 9 November 1938 (5)