Arthur Polack

(1885–1917)

Two men in uniform, two brothers, photographed in a studio in 1916: Arthur and Richard Polack.

It is the third year of the war and it will be the last time the brothers are together.

The older brother, Richard Polack, is standing on the right. In civilian life he worked as a salesman and resided in Heidelberg with his wife and children. The number on the cover of his spiked helmet and collar patches indicates that he was a member of the Twenty-Sixth Landsturm Infantry Battalion in Baden’s XIV Army Corps.

Arthur, his younger brother of five years, lived in their hometown Hamburg and was also married, as revealed by the wedding band on his hand. He is sitting on the left and is wearing a Prussian uniform. On his cap are the black, white, and red cockades of the German Empire and beneath them the Hanseatic cockades. He belonged to the Reserve Infantry Regiment Hamburg 76.

A Boy from Hamburg

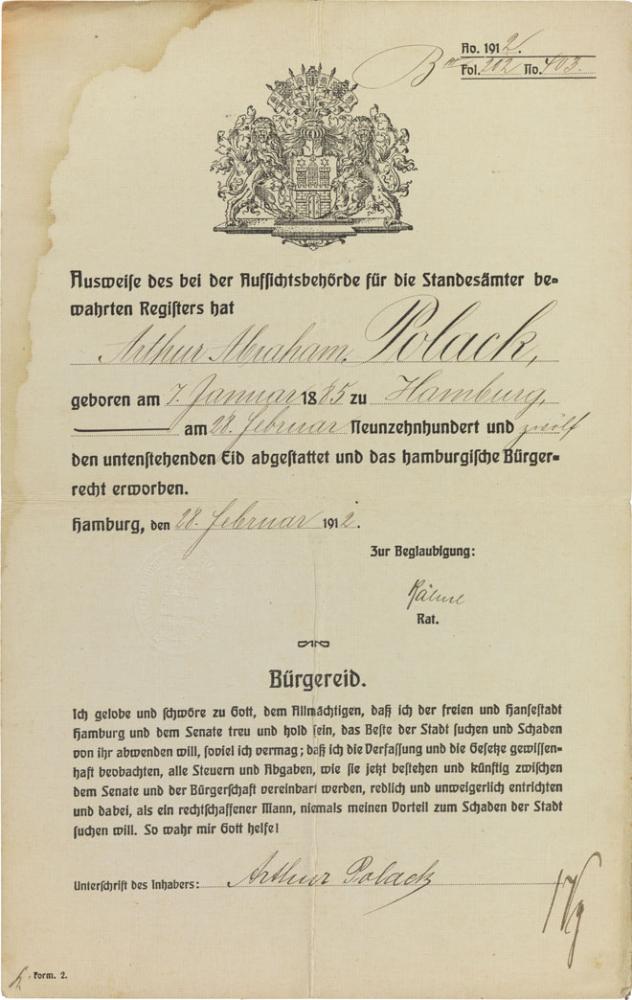

Arthur Polack was twenty-seven years old when he became a citizen of Hamburg in 1912. This made him eligible to vote in local elections.

X

X

Arthur (left) and Richard Polack (right), 1916; Jewish Museum Berlin, gift of Orah Young; photo: Jens Ziehe

He was born in the Hanseatic city, attended school there, and completed his business training there as well. Thereafter, he followed in his father’s footsteps, who was a traveling tobacco salesman. Polack established his own tobacco company that had its headquarters across from Hamburg’s Speicherstadt, or warehouse district.

Military Conscription

Arthur married his long-time fiancée Erna from Altona on 3 August 1914, immediately after the beginning of the war. His military conscription was most likely the reason why they decided to wed at precisely this time.

Details about his military service are not known. A military passport, salary book or other documents that could have told us more have not survived.

Horrors of War

X

X

Arthur Polack’s certificate of citizenship, Hamburg, 28 February 1912; Jewish Museum Berlin, gift of Orah Young; photo: Jens Ziehe

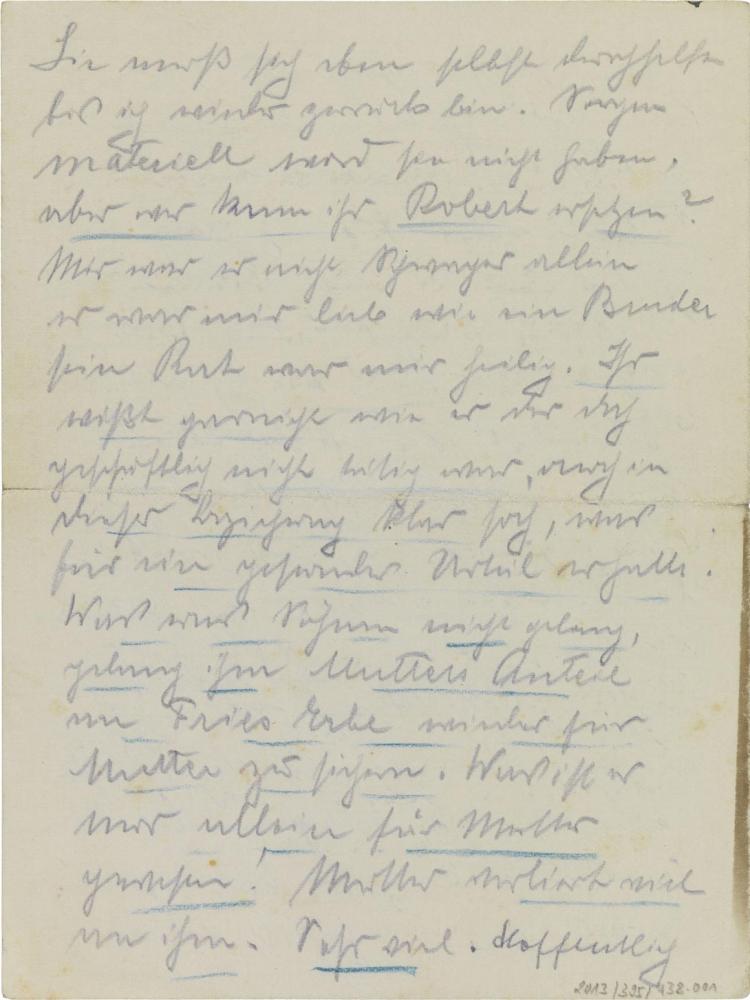

The only extant letter sent by Arthur Polack from the front is dated 29 June 1917, when he was serving near Arras in northern France. It was written to his cousin Anni Bredee and in it, Arthur openly expresses his thoughts and feelings. There is no trace of heroic valor or patriotic pride: he writes about how shocked he was by the death of his brother-in-law, who had fallen shortly before. He felt alone in his sadness, “sitting here, death before my eyes, its victims all around me,” while all his comrades were “desensitized.” He was also worried for his sister, who as a widow would now have to raise her two sons alone. And finally, he was concerned about his wife. He wanted to survive for her, “and yet it is impossible.” In view of the directness of the letter, it is remarkable that it got past the military censors.

Arthur Polack seems to have had a premonition of his own death in the face of the carnage that he was confronted with.

X

X

Arthur Polack as soldier in a gray field uniform, about 1916; Jewish Museum Berlin, gift of Orah Young; photo: Jens Ziehe

“All-time low”

Polack discussed experiences of antisemitism in his letter with extraordinary openness. He did not refer to the “Jewish Census” carried out some six months before the letter was written, which was a reaction to the widespread – and false – notion that Jews were attempting to shirk military service. However, he traced the fact that he remained a subordinate officer back to “a certain animosity towards the Old Testament.” Thinking of the way Jews had been denounced as “shirkers,” he bitterly concluded: “My patriotism will soon have reached its all-time low.”

Two and a half weeks later, Arthur Polack was dead.

Letter to His Parents

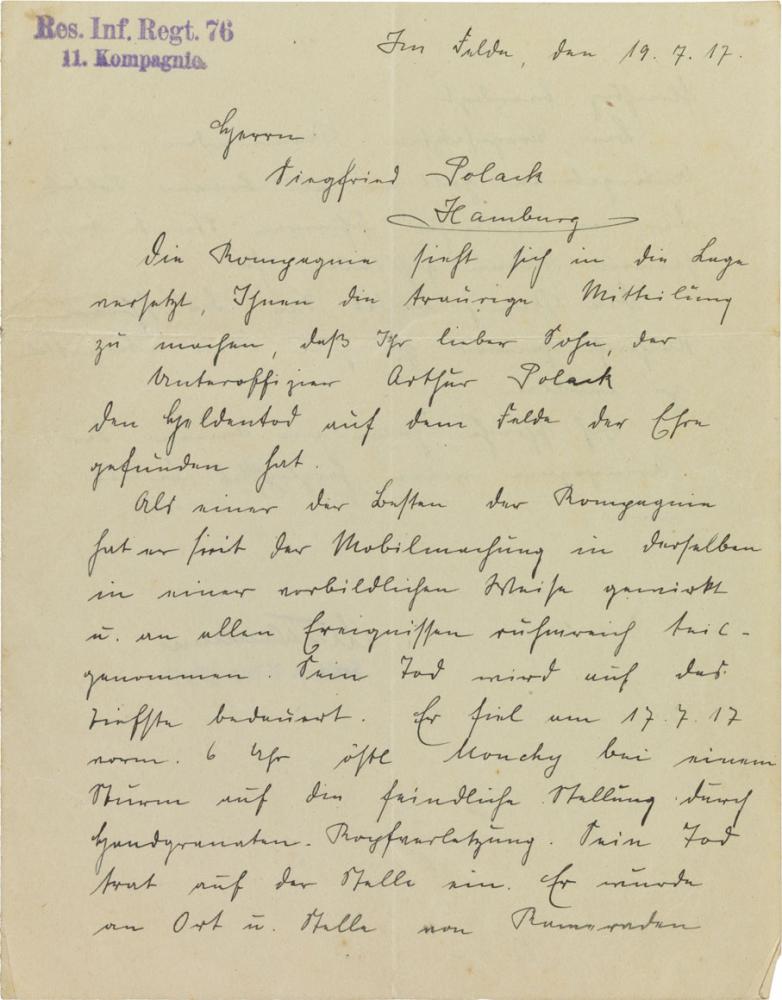

The 32-year-old died on 17 July 1917 at 6 in the morning “during an attack on an enemy position” east of Monchy-le-Preux. A hand grenade ended his life.

Message from the Company Commander with News of Arthur Polack’s Death

Message from the company commander with news of Arthur Polack’s death (page 1); 19 July 1917; Jewish Museum Berlin, gift of Orah Young; photo: Jens Ziehe

The company commander sent Polack’s parents in Hamburg the “sad news” that their son had “died a hero’s death on the field of honor.” He assured them that he “died on the spot” and did not suffer. The company commander asked Polack’s parents to inform his widow.

Final Resting Place

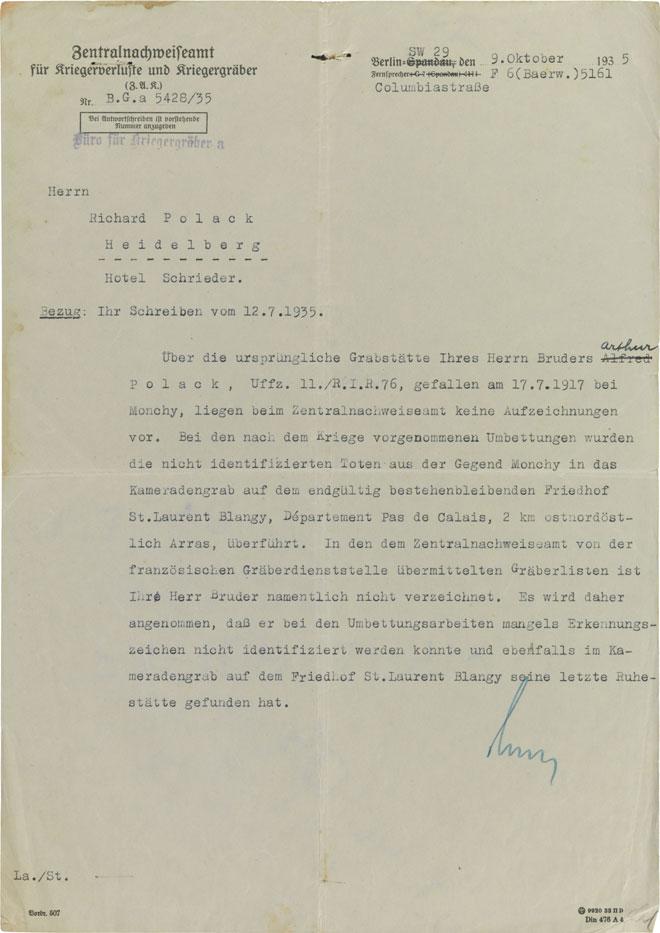

Fellow soldiers had initially “hastily buried” Polack at the site of his death.

It was only in 1935 that his brother Richard Polack – who had since emigrated to France and was only in Germany periodically – learned that Arthur’s remains had been reinterred at the St. Laurent-Blangy military cemetery.

Warrior’s Cult

In 1936, the Hanseatic City erected a memorial for the fallen soldiers of the Hamburg Infantry Regiment 76, to which Arthur Polack had belonged. Still standing today, it consists of a rectangular block made of coquina with a relief depicting marching soldiers. The engraving in the center reads: “Germany must live, even if we must die.”

The dedication ceremony was staged by the Nazis as a glorification of war and as propaganda for the coming conflict.

You can find more documents and photos related to Arthur Polack in our online-collection (in German).

Jörg Waßmer, Archive

X

X

Letter from the Central Office for War Fatalities and War Graves to Richard Polack; Berlin, 9 October 1935; Jewish Museum Berlin, gift of Orah Young; photo: Jens Ziehe

Citation recommendation:

Jörg Waßmer (2016), Arthur Polack

(1885–1917).

URL: www.jmberlin.de/en/node/3849

To the next biography: Ernst Marcus (1893–1917)

12 of 12,000: Fallen German-Jewish Soldiers in the First World War (12)