Media Library

Video and Audio Recordings of Events, Conference Documentation, and More

We record many of our lectures, conferences, and other events for you.

As most of our recordings are talks or lectures, they may also be suitable for people with visual impairments.

Eyewitness Talks

Eyewitness talk with Jack Weil, Video recording from 10 Mar 2025 (in German)

More information on the event

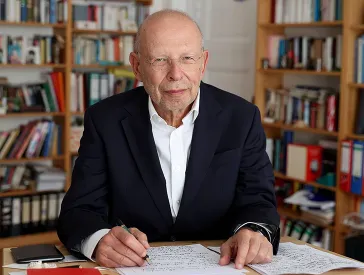

Eyewitness talk with Kurt Salomon Maier, recorded on 28 Oct 2024 (in German)

More information on the event

Herbert Zwartz: Hidden in Enschede, video recording from 16 Apr 2024

More information on the event (in German, with German subtitles)

Eyewitness talk with Ruth Weiss, recorded on 20 Sep 2022 (in German, with English and German subtitles)

More information on the event

Eyewitness talk with Harry Raymon, recorded on 28 Jan 2022 (in German)

More information on the event

Eyewitness talk with Eva Schloss, recorded on 21 Jan 2021 (in German, with English and German subtitles)

More information on the event

Eyewitness talk with Peter Schaul, recorded on 9 Nov 2020 (in German)

More information on the event

Eyewitness talk with Zvi Aviram, recorded on 16 Sep 2019 (in German)

More information on the event

Eyewitness talk with Sally Perel, recorded on 12 Jun 2019 (in German)

More information on the event

Eyewitness talk with Peter Neuhof, recorded on 3 Dec 2019 (in German)

More information on the event

Eyewitness talk with Hanni Levy, recorded on 25 Jun 2018 (in German)

More information on the event

Eyewitness talk with Anita Lasker Wallfisch, recorded on 28 May 2018 (in German)

More information on the event

Eyewitness talk with Margot Friedländer, recorded on 9 Apr 2018 (in German)

More information on the event

Eyewitness talk with Walter Frankenstein, recorded on 31 Jan 2018 (in German)

More information on the event

Eyewitness talk with Horst Selbiger, recorded on 11 Jan 2018 (in German)

More information on the event

Eyewitness talk with Kurt Roberg, recorded on 4 Dec 2017 (in German)

More information on the event

Eyewitness talk with Henry Wuga, recorded on 23 Oct 2017 (in German)

More information on the event

Eyewitness talk with Marko Feingold, recorded on 10 Oct 2016 (in German)

More information on the event

Eyewitness talk with Renate Lasker-Harpprecht and Anita Lasker Wallfisch, recorded on 1 Mar 2016 (in German)

More information on the event

Ukraine in Context: Interviews

Why is remembering Lviv’s Jewish heritage so important?

Interview with Sofia Dyak, historian and the director of the Center for Urban History in Lviv

How has Jewish life in Western Ukraine historically differed from that in Eastern Ukraine?

Historically, Ukraine was part of different states and different empires. If you think about what is now western Ukraine, it was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and then part of interwar Poland. Many people who were Jewish would speak German, would speak Polish, would write in Polish. And central, southern, and eastern Ukraine were part of the Russian Empire and the Pale of Settlement. Those regions had different languages, mostly Russian, but also Yiddish was spoken everywhere. That’s a big missing language in Ukraine.

And the difference was also sharpened by the very fact that Galicia became a part of the General Government when it was occupied by Nazi Germany in 1941. Many people just couldn’t escape. But many people did escape from central and eastern Ukraine as were part of the evacuation. In western Ukraine, there is much less continuity and more of a rupture. Those Jewish inhabitants of Lviv, Rivne, Stanyslaviv (now Ivano-Frankivsk), and towns such as Brody or Zolochiv who survived the horrors of occupation and the Holocaust generally left for Poland and then Israel and the United States.

Was the Jewish heritage of Lviv and the murder of a large part of its Jewish population by Nazi Germany remembered in Soviet Lviv?

At the very first months after the Red Army came to the city in late July 1944, you actually see quite a lot of materials in the local press about Nazi atrocities in the city. And then, as this more official framing or story of the war and occupation solidified in the Soviet Union, there was actually not much space for specificities, [let alone] the exceptionality of the murder of Jews as a genocide. This was wrapped up in the story of Soviet citizens, civilians. And you would not find memorials to Jews [who were] killed or Holocaust memorials. But going through some towns and villages, depending on the community, you might find inscriptions of names of civilians who were killed.

But if you think about private memory, it’s a whole different thing. People do tell stories. For some, for many, it’s a family story, because many Jewish people survived in the evacuation, were able to escape and come back, and this is a story about their relatives.

Has the official narrative changed since then?

The story says that things changed after 1991, but they were already changing with Perestroika in the late 1980s, when lots of topics surfaced. For example, the memorial to the Lviv Ghetto opened in the early 1990s. This discussion and initiative came [about] with the establishment of the Sholem Aleichem Jewish Culture Society. It’s a late Soviet story which became a story of the early independent Ukraine. Also, the story of the city was still largely Ukraine-focused, minus [anything] Soviet. Getting rid of Soviet things in the city, street names, the Lenin Monument. It was gone pretty quickly. And this was of course a challenge [for] the history of the city, which had a huge presence of Jewish Lvivians and Polish Lvivians, of how to incorporate that into the narrative of the history of the place.

It took time to learn about people’s stories. It’s learning about what happened. It’s learning how people lived. About organizations, about ideas, about artists, about the whole wealth of urban life in the city. And in some of the commemorative projects, part of that search is that there’s still so much to discover and find ways of making it visible. There are signs that are not made by us today but are preserved, uncovered, and made visible. These signs are inscriptions on the buildings, where you can read that there was a shop in Polish and Yiddish or some office or advertisement. The city’s layers, its cracks, come through on buildings. They speak if you want to listen and you’re ready to hear.

Why is remembering the city’s Jewish heritage so important from your perspective as a historian?

Why do we need to remember? I think, to be human. And I think that what makes us human is relations, relations to the place we inhabit, relations to people around [us], but also people who were around while we were not there. I think it’s a story of who we are. And I think that the more stories we can bring [forward] from the past, the more sensitive and, in a way, better human beings we can be. It is a matter of honor and of honoring the people who were before me, who lived a life in the city where I’m now living my life. I think that empathy can make Lviv as a city more Jewish in the ways it sees its past and in the way contemporary Lvivians relate to people who had to leave their homes and find refuge and a new home in the city, because right now Lviv is home to 150,000 displaced Ukrainian citizens.

Whose responsibility is it to honor the places and life stories to which these places testify?

I think basically everybody’s. There are big projects, but there is an infinity of small things you can do. If you happen to live in an old house, it helps to think “Who has lived here?” Doing a little internet research and figuring out who lived there. And treating that place with respect. Have sensitivity that there were people before me and there are people after me. And at some point, opening the door if somebody knocks or rings and says that my grandparents or my relatives lived here. These are little things which any of us contemporary inhabitants can do. And that’s not speaking of all the civil society, of museums, artists, municipalities, historians, professionals. These are actors and [stakeholders] who are important. And Jewish organizations, because there are many of them, and in Ukraine there is quite a vibrant Jewish life still there.

Is the memory of Lviv’s Jewish heritage endangered by the current war?

You never know: a bomb can fall onto the building of a museum or cultural center [at any time]. And I think most of all it’s because it brings massive displacement. If you think of cities like Kharkiv, cities like Dnipro and Kyiv and Odesa, they are really so close to the front line, and people were fleeing from these places. This displacement really endangers the existence of Jewish heritage in its most vital form: people.

In an interview in March 2022 you stated that Germany has the opportunity to rethink its relationship to Eastern European history. What did you mean by that?

It’s a fairly long story of the way the Second World War is referred to and the way the Soviet Union is too simplistically described as Russia, which it is not. And if you think about Eastern Europe and how to see it as a part of the Soviet Union... It actually was Belarus and Ukraine that bore the biggest toll of civilians and the occupation and also had a big and significant share in the Red Army. In Belarus, it’s a slightly different story right now. In Ukraine it’s also challenging how to retell the history of the Soviet period and how to acknowledge it or find a way of acknowledging it and being critical of it. In Germany... It’s a generalization but Eastern Europe has been quite overshadowed by Russia, and it’s more complicated, simply. There are more countries, there more societies there. Learning about that or seeing that really helps to revisit the way we are thinking about the last war and also [how we] act on this war.

Has Germany changed its approach in the last year?

I’ve seen that there are many events, publications, and interviews, and I think there [has been] a change toward more complex ways, of seeing not straight from Berlin to Moscow, but there are a couple of places in between. You sometimes think that it’s really a very high price of learning. What we are going through in Ukraine but also in Europe in general and in the world does make us rethink what we thought we knew.

The interview was conducted by Immanuel Ayx, Jewish Museum Berlin, in May 2023.

You can find a recording of the event on Lviv with Philippe Sands, Sofia Dyak and Marina Chernivsky on our website.

What characterizes Jewish Ukrainian’s memory culture?

For now, the Russian war of aggression has frozen debates over how to reconcile various memories within Ukraine. Ukrainian Jews are fighting in the ranks of the army, and President Volodymyr Zelensky is the most prominent symbol of the transformation of Jewish-Ukrainian relations since the start of the twentieth century.

Historically, from the Jewish perspective, the attempt to establish an independent Ukrainian nation-state was accompanied by antisemitic violence. One major conflict in modern history that was remembered differently by Jews and Ukrainians is the uprising led by the Ukrainian Cossack Hetman Bohdan Khmelnytsky against the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (1648–1657). To this day, many Ukrainians celebrate the rebellion as the first major national uprising, although it resulted in massive violence against Jews. Estimates put the number of Jewish deaths at around 18,000 – almost half the Jewish population of Ukraine at the time.

The greatest catastrophe for Jewish-Ukrainian relations was comprised by the events of the first half of the twentieth century. Like almost all European national movements, those in Russia and Ukraine were marked by antisemitism. Ukrainian nationalists cast Jews as the exploiters of the Ukrainian people, and old prejudices with roots in the Middle Ages and early modern times mixed with new stereotypes about Jews as the alleged profiteers of capitalism, but only in the 1920s and 1930s did radical antisemitism become one of the most influential currents in western Ukrainian nationalism. In central and eastern Ukraine, during the ensuing post-imperial civil war after the collapse of the Russian tsardom, Jews became the victims of anti-Jewish violence on a massive scale. In western Ukraine, the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN), established in Vienna in 1929, cooperated with the Nazi occupiers from Germany, starting in 1941. Even after OUN leaders were arrested, including Stepan Bandera, a considerable number of OUN members continued to place themselves at the SS’s disposal as local auxiliary policemen and helped identify Jews and hand them over to their murderers.

In Soviet Ukraine, which now encompassed western Ukraine due to the territorial shifts of the Second World War, the memory of the Holocaust was suppressed, as in all the republics of the Soviet Union. But in the “Thaw” after Stalin’s death in the late 1950s and early 1960s, the suppression of memory reached its limits. This is shown by the history of the site where the largest single massacre of Soviet Jews took place, the Babyn Yar Gorge. To mark the twenty-fifth anniversary of the massacre, a major commemorative ceremony was held in which non-Jewish Ukrainians participated and showed their solidarity with the victims. The memorial at Babyn Yar erected during the Soviet era had made no mention that the vast majority of people murdered there had been Jewish.

It is still very much the case that the Holodomor – the man-made famine planned by Stalin and his followers and extensively directed at the Ukrainian nation – is seen as the country’s “own” trauma, whereas the Holocaust is considered the “other” Jewish tragedy.

Text: Franziska Davies

You can find a comprehensive background article by Franziska Davies about Ukraine’s Jewish history in JMB Journal #24.

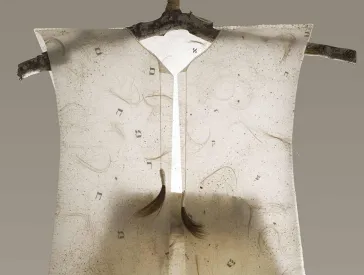

Illustration: The first ever Ukrainian postage stamp commemorates the Cossacks’ national uprising. Ukrainian envelope; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2022/23/0, gift of Leonid Dolgopiat

How has the commemoration of the Holocaust evolved in Ukraine from Soviet times to the present day?

Interview with Anna Medvedovska, historian, Institute for Holocaust Studies in Dnipro

What is your personal connection to Dnipro and its Jewish history and contemporary life?

I’m a historian. I research the Holocaust perception in Ukraine. And as for Dnipro, I consider the city my ancestral home because although I wasn’t born there, a few generations of my family before me lived in this city. And most of my life I spent there studying on the historical faculty.

Is there a specifically Soviet perspective on the Holocaust?

Yes, of course there is. Actually, to put it briefly, if we are talking about the official discourse in the Soviet Union, the Soviet authorities didn’t want to single out the Jews as a separate category of victims. They did not deny the Holocaust, but they gave the Jewish victims a different identity, a euphemistic identity: as Soviet citizens, peaceful Soviet citizens. The Holocaust never existed in the public discourse.

Has there been some kind of counter-narrative?

The scale of this tragedy is so huge that it was not possible to hide it even a few generations later. This memory was preserved in communication between people, both between Jewish people and between Jews and non-Jews. So everybody knew about it. They could even discuss it in private conversations, but not in public, not in books, not in newspapers. Soviet writers and the creative intelligentsia tried to bring the topic of the Holocaust into the public eye. But their pieces could not always reach the audience because of censorship.

Did commemoration change during the post-Soviet period?

These restrictions on commemoration and open public discussion were lifted back in the late 1980s. Of course, in the 1990s, after independence, everybody could research, everybody could talk, and everybody could spread knowledge about the Holocaust in Ukraine. But at the same time, the state did not take any official position on this issue. And all the initiative in commemoration, memorialization, and simply learning about or studying the Holocaust was in the hands of Jewish communities and private interested groups.

Are there other obstacles getting in the way of incorporating the history of the Holocaust in the Ukrainian national narrative?

That’s a very good question because there are many obstacles, frankly. But one of the most general obstacles I can extract directly from your question is a Ukrainian national narrative. What do we mean by this notion of a Ukrainian national narrative? That is something that after the Soviet Union collapsed, we had to invent from scratch. What do we need to include in it? What is it? What do we call the Ukrainian political nation?

And it is also important to note that as a part of the legacy of the Soviet Union, we inherited post-Soviet bureaucracy and post-Soviet historians who were trained and ready to fulfill the state’s orders. The paradigm cannot be changed immediately at once. It can take years, even decades. And schoolchildren and university students needed the textbook immediately. So, to incorporate the Holocaust into the Ukrainian national narrative, we first need to create this narrative and to understand the methodological foundation and approaches when creating this narrative. That is the main obstacle.

Are the discussions about competing memory narratives still ongoing despite the current war?

Right now we have such an agenda … it’s very difficult to compete. That is why I’m afraid not so many people are thinking and talking about the Holocaust now. But especially now, more and more Ukrainians are taking an interest in their own history. Because we can’t expect Ukrainian society to perceive the Holocaust as a part of its own history when there are so many chapters of Ukrainian history that are not perceived objectively, I would say.

There are many ethnicities in the Ukrainian army now and in Ukraine overall. There are Ukrainian people, Jewish people, Romanian people, Crimean Tatars, and many, many other peoples. And I’m convinced that after this war, it won’t be possible to write the history of Ukraine as only the history of ethnic Ukrainians.

The interview was conducted by Mirjam Bitter, Jewish Museum Berlin, in March 2023.

You can find a more comprehensive version of the interview with Anna Medvedovska on our website, as well as a recording of the event with Tetiana Portnova, Anna Medvedovska, and Oleg Rostovtsev.

How does contemporary literature from Chernivtsi engage with the city’s Jewish literary history?

Interview with Oxana Matiychuk, literary scholar and cultural manager in Chernivtsi

What is your relationship to Jewish literature from Chernivtsi?

My name is Oxana Matiychuk. I'm from Chernivtsi and wear several hats: First, I'm a lecturer in literary history at the University of Chernivtsi. I also work at the university's International Office. I also run the cultural association in Chernivtsi officially named the German-Ukrainian Cultural Society, a partner of the Goethe Institute.

In both my profession and my cultural management work, I am inevitably very involved with literature. And I also wrote my dissertation about Jewish German-language literature from Bukovina.

Can you tell us about the contemporary literary scene in Chernivtsi?

The literary scene is truly very lively. A few of the authors are already international names. For example, Chrystja Wenhrynjuk has been translated, and Maxym Dupeschko has also been translated into several languages. And as a lecturer in literature I know a few current students, a few voices who doubtless will be famous in the future, or could become famous. Absolutely enormous talents.

What role does Jewish literary heritage play for the young writers?

I notice that particularly those who personally aspire to careers in literature or the arts, not necessarily literature, are now particularly interested in the literature that was written before 1940. In other words, in the literature of Bukovina that has entered literary history in the West or in some cases the canon.

There are several contributing factors including the Meridian Czernowitz literary festival. The name makes a very clear allusion to Paul Celan, to one of his speeches. And because, thankfully, there are so many translations, foremost thanks to the translator and professor Peter Rychlo, non-German-speakers are also able to receive this work. In order to reflect on it, obviously you need to be able to receive it. And the complete works of Paul Celan are available. There are many translations of Rose Ausländer. There are translations of the work of Selma Meerbaum-Eisinger. It's really quite a lot, thanks to the tireless Peter Rychlo.

And there are allusions to these authors and texts in the writings of young authors. Beyond that, there are very many art projetcs that draw on this rich literary heritage. And because, at least before the big war, we did a lot of cultural management work, we notice the huge potential of Bukovina's multinational, multilingual literature. Our NGO has many projects related to the work of either Rose Ausländer or Paul Celan, or Selma as well. It's truly a limitless source of ideas, stimuli, and inspiration.

Does literature in Yiddish and Hebrew play a role as well?

Unfortunately less so. Because there are virtually no translations from the Yiddish. Yiddish is sadly dying out in Bukovina. Until a few years ago, there was even a broadcast in Yiddish: Dos Yidishe Vort. But by now, the last Yiddish-speakers in Chernivtsi are no longer with us. Which is why Yiddish literature, the truly magnificent literature by Itzik Manger, Eliezer Steinbarg, is waiting for its translators. There is just too little that could be received.

From the Hebrew, Aharon Appelfeld has been translated very well, for example. And his works that are available in Ukrainian and German are well-received.

How has Chernivtsi as a literary topos changed compared to the pre-1940 period?

I've noticed efforts in recent years to examine Chernivtsi's history not just from one perspective, as before. For example, from the Ukrainian, Romanian, or Jewish perspective. But, for example Maxym Dupeshko's novel, with its long title, in Ukrainian, “A Story Worthy of a Whole Apple Orchard,” makes the first attempt in recent history to portray Chernivtsi's history from multiple perspectives. Truly a very exciting attempt.

But I also notice it in poems... Many short forms, lots of poetry is being written. With the youngest generation there are also references, attempts to talk about the past, about the authors, about the art. But that's really the latest development. I think it really required time to approach this history, before it was possible to talk about it.

What do you find notable about current Ukrainian literature?

In light of the war here, there are many different processes underway, also in the art sector. For example, many Russian-language authors feel conflicted about their native language, Russian. And there are also very exciting – setting aside the tragedy for a moment – interesting debates about Russian as a native language. For example, the cases of Volodymyr Rafeienko, Iya Kiva, and Lyubov Yakymchuk. All very well-known authors who are mostly from eastern Ukraine who suddenly find themselves in the situation that their mother tongue has become the language of the murderors.

You can't get around seeing the parallels to how it was for the Jewish population, including Jewish writers, suddenly in 1941. Many Jews, many educated Jews in [then] Czernowitz naturally spoke German. They chose German-language literature and culture as their reference point. Obviously this resulted in linguistic traumas. The coping mechanisms they developed ranged widely, but it's also fascinating, from the perspective of time. I see some connections to the authors of today who are forced to grapple so painfully with this language issue.

It would certainly be an interesting subject for research, for someone outside the situation, not someone personally embroiled in it.

Why is your German-Jewish cultural organization called “Gedankendach”?

The name, the word “Gedankendach” [thought-roof], comes from Rose Ausländer. When we founded the association, we looked for an interesting name. There were a few conventional ones that we were very against adopting. Then our DAAD editor at the time found the word in the poem “Architects.” We were extremely excited and enthusiastic because it captured the essence, our idea for how we wanted to shape our work. It also fit the aspect that, of course, the starting point for our work was the word, the idea, the thought. So we adopted this word, this coinage for ourselves.

The interview was conducted by Mirjam Bitter; Jewish Museum Berlin, Nov 2022

You can find a recording of the event with Oxana Matiychuk, Peter Rychlo, and Mykola Kushnir on our website.

Why did the historical Czernowitz produce so many famous Jewish authors?

In the second half of the nineteenth century, Czernowitz developed at the eastern periphery of the Habsburg Monarchy into a city with all the administrative and cultural attributes of an Austrian Imperial city. Far from Vienna, in multilingual Bukovina, it was a place where large populations of Jews, Germans, Ukrainians, Romanians, and Poles lived. The Jewish population was guaranteed full civil rights, which allowed them to develop both politically and culturally.

There are numerous works in Yiddish, but also Hebrew works written by authors who immigrated to Israel after the Second World War, such as Aharon Appelfeld (1932–2018) and Manfred Winkler (1922–2014). Most of the Jewish literature from Czernowitz, however, was written in German, and the poetry and life of Paul Celan (1920–1970), Rose Ausländer (1901–1988), and Selma Meerbaum-Eisinger (1924–1942) have continued to the present day to attract considerable interest.

Starting in the 1930s, more than fifty authors published works in local newspapers, had their first books published, and—unrelated to Vienna influences—established the first independent, modern Bukovina literature. The often-described insular character of Bukovina and the limited communicative space fostered poetic encounters in the short period before the war that ended tragically with ghettoization and the deportation and death of tens of thousands of Bukovinian Jews in the camps of Transnistria and beyond the Southern Bug in the years from 1941 to 1944.

After 1945, this literary landscape was created anew and expanded through the Czernowitz exiles in Israel, Germany, the United States, Romania, and France, whereby their experiences as survivors, as people in search of a home, and as memory bearers found expression in their literary works.

Since 1991, Czernowitz/Chernivtsi is a Ukrainian city where the historical and literary heritage does not only remember, but also refers to the present and future in transcultural projects.

Text: Markus Winkler

You can find the unabridged version of Markus Winkler’s essay about Czernowitz and Jewish literature in JMB Journal #24.

Illustration: Andree Volkmann, Portrait of Paul Celan (1920–1970), 2020; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession NDA/963/60

Why was Kyiv one of the most important centers of Yiddish literature?

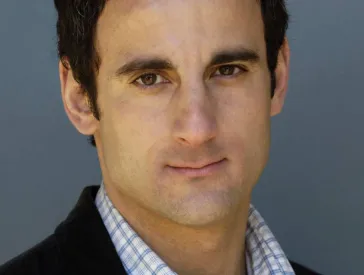

Interview with Gennady Estraikh, Professor of Soviet Yiddish Culture and History at New York University

What were the centers of Yiddish literature in the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union?

In the Russian Empire, the main center for Yiddish culture was of course Warsaw. Warsaw was the center of predominantly commercial Yiddish culture, publishing newspapers with a high circulation, and publishing books: the main publishers were in Warsaw. And there was a parallel development in Vilna [Vilnius] and in Kyiv. They opposed this commercial lowbrow culture and wanted to develop highbrow Yiddish literature. Vilna was good at producing some theoreticians, and Kyiv was good at producing, as it happened, Yiddish writers. So, this was a cooperation between two things. When the revolution took place, followed by the civil war, and the Russian Empire had disintegrated, Warsaw was outside Soviet territory, Vilna was outside Soviet territory, so Kyiv remained the main center. As simple as that. And actually, the Kyiv group – it was even later called the Kyiv group of Yiddish writers – dominated the Yiddish literary scene in the Soviet Union throughout the entire period.

Why Kyiv?

Kyiv was a rich city. It was outside the Pale of Jewish Settlement. And it happened that Kyiv’s Jewish population had a very peculiar structure because it was difficult for a regular Jewish family or individual to settle in Kyiv. Kyiv was a place where a very significant number of wealthy Jews lived – some of them fabulously wealthy. At the same time, there was also a segment of not wealthy Jews, who got such permission because they qualified in various fields, and as a result they were allowed to settle. As you know, Sholem Aleichem used to live in Kyiv for a long period of time apparently. This was important. Also, in many cases we see the following story: a rich family was allowed to invite teachers for their children. And of course, a rich family would find the best and some remarkable – whatever remarkable meant at that time – person would become a teacher. And at the same time, such a person would write in Hebrew, and then Sholem Aleichem encouraged this person to write in Yiddish. So, there was some basis. And Kyiv in general was one of the places where many Jews were highly educated or interested in education and some of them became interested in Yiddish.

How did the Night of the Murdered Poets affect the use of Yiddish language and culture in Ukraine?

First of all, I am not a great fan of the term “the night of the murdered poets.” Because on 12 August 1952, thirteen people were executed, and only four of them were poets. To give that name to this tragic event, “murdered poets,” somehow makes the other people irrelevant. I don’t believe it’s fair, to be honest.

But in any case, what is really significant is that this was the night when the four poets and one prose writer, Dovid Bergelson, were executed, and they were the best writers. They were really the best writers, Yiddish writers, the most influential, some trend-setting writers, effectively literary celebrities. That left a void that was impossible to fill afterwards. As did the [surrounding] events, not only of 12 August 1952 but in general of the persecution of Yiddish writers, because many of them, many more Yiddish writers ended up in the Gulag, in the labor camps.

The bulk of them survived, but still many of them came out really physically broken, psychologically broken. And this whole tragic development brought, I would say, poison into this literature milieu in general, in Ukraine or in general in the Soviet Union. Because people somehow divided into two groups: those who had been in the camps and those who hadn’t been arrested. So as a result, somehow it was divided: were those who survived in the camps more important than those somehow ignored by the secret police? In addition, during the interrogations many Yiddish writers – or some of them, I don’t know the exact number – were forced to support some accusations against their colleagues under pressure. And as a result, Yiddish writers and this whole circle came out of this experience: “He denounced me,” “No, he denounced me.”

In addition, it also of course made them, or at least the bulk of them careful, or maybe too careful. It was fear of course. They came with this experience of being in danger.

Are the events of 12 August 1952 commonly commemorated?

During almost the entire Soviet period, the event of a trial and execution of a group of these figures from the Jewish Antifascist Committee officially didn’t exist. The authorities didn’t recognize it. The day of 12 August 1952 couldn’t be mentioned. Sometimes people would find a way to mention it. For example, in 1984 a dictionary came out, a Russian-Yiddish dictionary. The editor introduced an example in the entry for the number “twelve.” There were no examples under the entries for “eleven” or “thirteen,” but for the entry on “twelve,” he introduced an example: 12 August. And you know it is somehow a hidden memorial.

Officially it became possible to mention the events around 12 August 1952 and to write about them as late as December 1989. [At that point] some of the surviving writers started writing their memoirs. And once again, it was even a competition, a bitter competition between the memoirs. So, during the remaining part of the Soviet period, there was a trace of what had happened in and around 1952.

What role does Yiddish play for Jews from Ukraine today?

I don’t know exactly because I left. I left Ukraine almost fifty years ago and the Soviet Union more than thirty years ago. But from what I know, unfortunately it’s minimal. There is some interest. Some people learn Yiddish, and there are people who translate from Yiddish. Something maybe came with the revival of religious life, because quite often it’s Hasidic, and some elements of Yiddish, but… You know, in America there is this intensively criticized culture of blackface. And one of the American cultural historians introduced the term “Jewface.” I believe it’s an interesting term. You know, it is all dancing, cozy, Jewish. If it’s a Jewish dance, then it’s with sidelocks and doing this body language or whatever. So, this kind of performances, Yiddish songs. Sometimes I find it difficult to listen to because it’s not Yiddish, but it’s a kind of Yiddish.

In any case, it is quite sad and the influences…Maybe we can compare it with Poland. Whereas in Poland they managed somehow (it is known how, but we don’t have time to explain here) to educate quite a significant group of scholars who produce very interesting stuff around Yiddish, history of Yiddish and so on –people seriously dealing with Yiddish. Unfortunately, not only in Ukraine but more or less in the entire Soviet Union, this didn’t happen. There are no schools, academic schools dealing with Yiddish. There are individuals, but it is minimal, marginal.

Is there a Jewish culture of resistance to Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine?

I don’t know. Let’s leave it to scholars to [answer] in a few years’ time, when the dust has more or less settled. The problem is, and I had a chance to see it and to listen to it, that in quite a significant number of cases, Jews react – or at least initially; maybe afterwards it changed, but I know of such a reaction – by applying history.

History is dangerous, dangerous stuff in general. History is important for historians of course, and historians are always thrilled when something related to history is being read and discussed on so on. But if you take something from history and apply it to a contemporary situation, it can be tricky. Some people recall Bohdan Khmelnytsky 1648–49. And to take this 1648–49 as an argument in a discussion about the Ukrainians in 2022 is a bit ridiculous. Or maybe even to use the events of the civil war and even the Holocaust. Still, how many years we are from the end of the Second World War? People forget about the fact that the bulk of the Ukrainian population voted for a Jewish president. Somehow, they find it less important than Bohdan Khmelnytsky. So, the reaction is mixed.

In addition, in the introduction to one of his novels, From the Fair, Sholem Aleichem writes that a Jew is like a carpenter. A carpenter lives and dies and a Jew also lives and dies. In this sense a Soviet Jew, a former Soviet Jew, is first of all, or quite often first of all, a product of the Soviet education, of the Soviet experience, of Soviet social engineering. We don’t know which of the factors played a more important role, the fact that this person is Jewish or the fact that this person is Soviet, or post-Soviet. Quite often the Soviet identity and Soviet background is stronger than the Jewishness. So what share of Ukrainian or Soviet Jews are on the Ukrainian side and what share on the side of Russia, I don’t know. First of all, how to count. I hope that the bulk is on the Ukrainian side, but I also know that there are people who are really quite pro-Putin, and then they have their argument and quite often once again Bohdan Khmelnytsky, [Symon] Petliura and all this can play a role. Especially, as Ukrainian Jews in Ukraine, the majority of them, were culturally more Russified. They would send their children to Russian schools. Russian was predominantly the language of their families, of their education, and many of them looked down at Ukrainian. So it was a kind of a high-language/low-language [situation]. But in any case, let’s leave it to people who research it separately.

The interview was conducted by Immanuel Ayx; Jewish Museum Berlin, Aug 2022

You can find a recording of Gennady Estraikh’s speech about history and legacies of 12 August 1952 on the webpage for the Symposium on the 70th anniversary.

As a writer and eyewitness to the events of the current war, what can you tell us about Jewish life in Kharkiv?

Interview with Serhij Zhadan,

author and the winner of the 2022 Peace Prize of the German Book Trade.

Can you tell us a bit about Jewish life in Kharkiv?

I’d rather talk about how the self-perception of many Kharkivites, many Ukrainians, is changing, how the relationship to our own country is changing regardless of nationality. For example, I’ve seen how many Ukrainian Jews today, in recent years, have been supporting Ukraine. They’re making a real effort to identify with this country, with its future, and oppose the Russian occupation. This is real news, those are really big changes in the life of the country and society.

Because if you remember the ’90s, or even the 2000s, the Jewish community or, for example, the ethnic Russians and other minorities lived their own lives. They didn’t always identify with Ukraine, with the Ukrainian state.

Today it’s entirely different. Today Ukrainian society is in fact very united. Today, ethnic Ukrainians, Jews, ethnic Russians, Crimean Tatars, and other nationalities who are living in Ukraine or are Ukrainian citizens are all striving to defend Ukraine together.

Which is why, when Russian propaganda tries to justify this war, this invasion using the narrative and idea of “de-Nazification” by claiming that Nazis are in power in Kyiv, that Ukrainian society is guided by Nazi ideology it is an enormous lie. This is simply untrue. We Ukrainians are demonstrating today that we are united most of all around the idea of Ukraine as a state regardless of our ethnic identities and that all these people today are a real political nation. We are all Ukrainians defending our country.

It makes me especially angry. It’s uncomfortable to hear. Why? Because I’ve lived in Kharkiv for 30 years. Kharkiv is a truly multinational city, an open city. I talked about that today on the panel. Various different nationalities have always lived together very peacefully. They’ve loved this city and still do.

When the war started, many Kharkivites started really working towards victory, mutually supporting each other. I know a lot of people from the Jewish community in Kharkiv, and they don’t see themselves as separate, they are united with the Ukrainians, they feel part of the country, especially because they understand that this is their country that needs to be defended today.

What can art and culture offer in the current situation?

Well, for one thing, literature can document everything that happens around us. Writers can serve as witnesses to events. I believe that is one of culture’s tasks, its function, and this function is very important.

And at the same time, culture is a space where we always feel somewhat normal and balanced. In any case, we associate culture with normal life, with education, with our background, with our education. And that’s why, even today, it’s important for people – whether on the front lines or deep behind them – to listen to music, to read books, and to know that this aspect of culture exists, that there’s this big field of culture.

Your book Sky Above Kharkiv, now available in German and English, consists of your Facebook posts during the war. Do you think it will influence your future writing?

No, what can I say... I don’t think that this Facebook style will have much impact on my writing. It was not a literary experience for me. It was a social experience: I simply tried to document everything that was happening to me. I didn’t write this journal to make a book out of it. The idea for the book came later. At the time, it was simply important to be able to remember those events later, not to lose it all.

And what will our literature be like in the future? To be honest, I’m not ready to make predictions. It’s too soon to say because we’re now in the midst of a huge, dramatic, and bloody upheaval. Most of all, we should survive ourselves and preserve our country so that we can have a future.

The interview was conducted by Mirjam Bitter; Jewish Museum Berlin, Oct 2022

A recording of the event with Serhij Zhadan on 9 October 2022 will soon be available on our media library.

How has the current war affected life in Kharkiv’s Jewish community?

An interview with Alexander Kaganovsky, chair of the Jewish community in Kharkiv, who has fled Kharkiv for Hamburg

What was Jewish life in Kharkiv like before the Russian war of aggression?

Our community is one of the most vibrant in Ukraine. We have all the necessary Jewish infrastructure. There’s a school, a kindergarten, a synagogue. There are regular services, holidays are celebrated.

Recent history, starting 30 years ago when Chief Rabbi Moshe Moskovitz arrived, has been very eventful. A lot has been accomplished: Jewish life in Kharkiv has risen from the dead.

What have your responsibilities been in the community?

As the chair of the community, I had a wide variety of functions. One of them was communicating with the authorities: I represented the community to all public agencies. Or, for example, I put together invitations for visitors from abroad. All of the community’s activities passed through me in one way or another.

Also, for more than 25 years, I’ve been editor in chief of our newspaper “Geulah.” It’s a very good paper, and a very popular one, not only in Kharkiv. We have readers and subscribers around the globe.

How is the Jewish community of Kharkiv doing now?

Our Chief Rabbi has returned to Kharkiv. Despite very dangerous circumstances, he went back with his whole family.

Rosh Hashanah was celebrated of course, just as it should be. There were many humanitarian packages, which weren’t only distributed to Jews. Truly, hundreds of packages. We help all the residents of the city and the Kharkiv Raion. We distribute food.

Prayer services happen at the synagogue daily skipping a single one. Even when the rabbi wasn’t there, services were held regularly, like in the good days.

The services went on despite bombardments?

Yes, yes, under bombardments. Many people sheltered at the synagogue because moving around was too dangerous. And there are people who know how to lead services.

When it all started, people came to the synagogue simply looking for shelter. A literal refuge from bombs because all the subway stations were full of people hiding from gunfire and bombardments. Everyone who came was taken in.

Overall, it must be said that the community passed the most terrible tests with flying colors. The city center was bombarded and the synagogue is nearby. All the sanctuary windows burst. Still, all the people of Kharkhiv wherever they were tried to help our community – with all the means at their disposal. Particularly worthy of respect are those who remained in Kharkiv and did this tremendous work. Those continuing their work to help the city’s residents.

How did you make it to Hamburg? And how are you doing there?

The journey was complicated, via western Ukraine and then Budapest.

When I arrived in Hamburg I immediately got in touch with the State Rabbi of Hamburg, Rabbi Schlomo Bistritzky. And the Jewish community whose members helped us so much. We couldn’t have done it without them – not knowing the language. And because everything’s so different: different rules, different circumstances.

When did you leave, and why did you choose Hamburg?

Because our rabbi got in touch with Rabbi Shlomo Bistritzky and he recommended it.

We left Kharkiv a while later. On Purim, I was already in Budapest. We spent five days there then arrived in Hamburg in northern Germany. At first we thought about going to Kiel but Rabbi Shlomo Bistritzky invited us to Hamburg.

How do you like Hamburg – the city and the community?

It’s a wonderful city and a wonderful community! We were given a very heartfelt welcome. We got a lot of help and so much warmth. You can feel the people’s warmth.

Hamburg is a very beautiful city! To be honest, I didn’t expect that the city is so green and beautiful.

For now I’m occupied with bureaucracy and paperwork and day-to-day life.

The area around the Alster, the city center, the center of Hamburg is gorgeous.

Is Jewish life in Hamburg different from Jewish life in Kharkiv?

Everything is very different. Of course it’s all quite different here. In Kharkiv, the community was our family. We all built it up together. I’m not yet so familiar with things here. But it’s apparent that the community sticks together and is well organized. There is spiritual leadership, it’s palpable.

Differences? The order of services is a bit different than in Kharkiv. There are a few differences. But overall there are many commonalities.

Do the Jewish communities in German help the refugees from Ukraine?

Yes! The community helped with both organizing paperwork and appointments with the authorities. Without this help, we would have been in serious trouble. As soon as we arrived in Hamburg we were put up at a hotel. This was all possible thanks to the tremendous work of the Jewish community of Hamburg.

Your Chief Rabbi has now returned to Kharkiv. Are you considering going back?

In my mind I’m still in Kharkiv, no matter how well I’ve been doing in Hamburg. I have dedicated 30 years of my life to the community in Kharkiv.

I wish for there finally to be peace again so I can return to my city.

I would like to wish everyone a good and sweet New Year with peace, well-being, and health! Thank you!

The interview was conducted by Sofya Chernykh; Jewish Museum Berlin, Sep 2022

What does it mean to be Jewish in Odesa?

Interview with Nikolay Karabinovych, artist and musician from Odesa

What does it mean to be Jewish in Odesa?

It’s different than being a Jew in other places in Ukraine because of Odesa’s history. It’s not complicated nowadays, although it was in the past. Still there is some kind of complexity to it which has to do with the history and the past. The first officially recorded anti-Jewish pogroms took place in Odesa in the 19th century. But to understand what it means to be Jewish in Odesa means looking not only at the history but also at the privilege of being an outsider and part of a minority. If you look at it from this perspective it helps you perceive the reality in depth.

What is the spirit of Odesa to you?

It’s a very complex question. The literature is very important for the spirit. Yiddish and Hebrew are important. But also the architecture, the many synagogues. A lot of houses were built by Jewish people who shaped the incredible architecture. The spirit is a combination of all these things. It is difficult to define the spirit because it is shaped by people today as well as by what happened in the past: the immigration, the pogroms, the Soviet repression. It all influenced today’s spirit. And it makes it difficult to identify an original spirit.

What got you interested in researching Jewish history and Jewish music from Odesa?

My passion for music comes from my understanding of music as a general and understandable language with which one communicates, expresses oneself and shares. Listening to music evokes emotions. Whether you listen to wedding music you used to celebrate and party to or you listen to an incredibly sad song about old tragedies. Music helps you feel and understand the complexity of a situation. And of course, music from Odesa is incredibly interesting and important for the whole Klezmer-movement. A lot of songs were originally played by people on the streets and backyards of Odesa. And because of the presence of different minorities the music styles in the city were mixed.

How have the different minorities shaped the city?

I don’t like the term multicultural, but it’s a suitable definition of the reality of Odesa because it is a multicultural city. Romanians, Italians, Roma people, Greeks and French used to live there. They built the city. There was a former Ottoman Empire castle called Khadjibey for example. Then a lot of Jews came, a lot of Greeks in a first wave of diasporas. The city was a melting pot in the past. After the Soviet revolution it became less diverse than before. After the Second World War, only traces of the diasporas and the minorities who used to live in Odesa remained.

Do you see yourself as part of an Odesa diaspora?

I perceive myself as part of an Odesa diaspora. I grew up there and my body of work mostly originates from my background in Odesa, from being a Jew in Ukrainian Odesa. It’s the undeniable fundament one can’t escape from.

How does your background influence your work?

Last year I did an exhibition at the Jewish Museum of Belgium in Brussels. The exhibition was called Why do you stand at the door? It focused on Jewish literature and the Jewish diaspora in Belgium. While researching in the collection of the museum, I found a painter called Ossip Siniaver. He was born more than 100 years ago on the same street where I used to live. He had an incredible biography. He migrated to Belgium, studied there and became known for his paintings of industrial landscapes, trains, the industrial culture and infrastructure. In an homage to his work, I placed one of his painting next to my video As Far As Possible, which I shot in Odesa and which tells the history of Odesa’s Salt lake Kuyalnik.

The interview was conducted by Signe Rossbach, Jewish Museum Berlin, in January 2023.

On our website you can find a recording of the event with Mikhail Rashkovetsky, Anna Misyuk and Nikolay Karabinovych.

What made Odesa a central site of Jewish utopian dreams?

Interview with Anna Misyuk, former curator of the Odesa Literary Museum

What is your personal relationship with Odesa?

I was born in Odesa in 1953, just after Stalin’s death. That was my happy beginning, being born after Stalin’s death. I spent my childhood and teenage years in Odesa. In 1979, I started working for the Odesa Literary Museum.

What made Odesa a central site of Jewish-Ukrainian culture and Jewish utopian dreams?

The spirit of Odesa probably emerged together with the city, with Odesa’s harbor. It was the time of new ideas and new kinds of life. And this spirit: a city of free people, a city of people who choose this place for their lives, by their own will, and an open city, open to the sea, a city full of free winds.

Another place, another space, another cultural spirit. And from the mid-nineteenth century, more and more authors, and even officials, began to connect this spirit of Odesa with Jewish people, with the Jewish spirit.

In Odesa, Jews were locals. It was the city of immigrants and resettlers, and Jews, together with others, began to build this city and the life of this city. So it was their city.

How did Odesa become a center of Zionism?

Maybe more than 70% of students at different levels in Odesa were Jewish. In this period, Odesa took the third place for educational level in the Russian empire, after St. Petersburg and Warsaw. Educated people are people who read. And authors came to this place because they wanted to be close to their readers.

And Hayim Nahman Bialik, a young Jewish poet, Hebrew poet, was the first with Zionist ideas who came to Odesa.

In 1881 there was a great pogrom in the Russian Empire. And after this pogrom, Leon Pinsker, Leib Pinsker, Lev Pinsker, he had many names – European name: Leon, Yiddish name: Leib, and Russian name: Lev – so Pinsker, Dr. Pinsker, one of the leaders of Haskalah in Odesa, of this enlightenment movement. At this moment he said: “That’s enough.” He went to Berlin.

He said that in Odesa we laid stones in the foundation of this city with our own hands. He said, but these stones began to cry: “Go away.” These stones that we put into the foundation with our own hands.

But at last he returned to Odesa and organized the first Zionist organization. Of course, they did not know such words “Zionist.” They called themselves Palestine-philes. Those who love Palestine.

Until the 1920s, thousands of people resettled to Eretz Israel thanks to the support of this committee.

In 1922, the new Soviet power closed and forbade all Zionist organizations and their activity. The activists were arrested and then exiled to Kazakhstan or Siberia. And so, the Zionist movement was stopped in the Soviet Union and in Odesa.

Is there anything left of the spirit of Odesa today?

Of course, nowadays Odesa has rather changed, both the Odesa spirit … and Odesa life. Now, especially in the period of the war of this … of these hostile events, it’s impossible. It’s impossible even to believe that this is happening in our time…

But, you know, many of my friends in Odesa – Ukrainians, Russians – feel that if the synagogue is operating, that if rabbis have returned to Odesa in this time period – there’s a chance for stability, stabilization. Because it’s impossible to imagine Odesa without Jews.

The interview was conducted by Mirjam Bitter, Jewish Museum Berlin, in January 2023.

You can find a more comprehensive version of the interview with Anna Misyuk on our website, as well as a recording of the event with Anna Misyuk, Mikhail Rashkovetsky, and Nikolay Karabinovych.

Why do some Hasidic Jews make a pilgrimage to Ukraine?

In the eighteenth century, the regions of Podolia and Volhynia (now mainly in Ukraine) were the cradle of Hasidism, a mystical movement that emerged in the context of the messianic expectations of the day. Hasidism spread over large parts of Eastern Europe. Today Hasidic Jews can be found all over the world, and every year tens of thousands of them make a pilgrimage to the Ukrainian town of Uman, where one of the founders of Hasidism, Rabbi Nachman, is buried.

Hasidism emerged in the context of shtetlekh (singular: shtetl), small and medium-sized towns with predominant or large populations of Yiddish-speaking Jews. These communities originated on the estates of Polish aristocrats, where the Jewish population in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth enjoyed many freedoms. This was one reason local farmers, many of whom were Ukrainian speakers in eastern Poland, saw Jews as representatives of the Polish nobility and thus as their exploiters. Life in the shtetl was often characterized by immense poverty, however. At the same time, it was a place that produced its own cultural traditions and economies. More recent research has also emphasized that the shtetl was not nearly as isolated as has often been portrayed. The nineteenth century saw the emergence of shtetl literature and a flourishing Yiddish press. Today, the shtetl has taken on mythical proportions as a place that embodies the world of East European Jewry that was destroyed by the Germans.

Text: Franziska Davies

You can find a comprehensive background article by Franziska Davies about Ukraine’s Jewish history in JMB Journal #24.

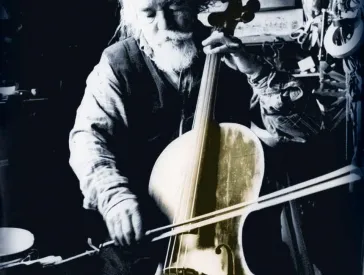

Illustration: Jakob Steinhardt, Dancing Hasidim (Simhat Torah), oil on canvas, 1934; Jewish Museum Berlin, purchased with funds provided by Stiftung DKLB. Further information on this object can be found in our online collections (in German)

What significance does the war have for Ukrainian society?

Interview with Marina Chernivsky, psychologist and behavioral scientist, born in Lviv, raised in Israel and living in Berlin since 2001:

The war has not only etched itself into individual memory, but has traumatized all of society. The postwar period will come and the war will occupy Ukrainian society for a long time. I’m confident that because of the extensive democratization process, the changed political situation, and the strong and growing civil society, Ukrainians will navigate this process well. Even today, I see tremendous resilience and cohesion, which are giving (back) to individuals a sense of their collective capacity to act. The fabric of society damaged and pierced by the war will mend, though not without consequences. Scars will remain.

The interview was conducted by Marie Naumann, Jewish Museum Berlin, in 2022.

You can find a more comprehensive version of the interview with Marina Chernivsky on our website, as well as a recording of the event on Lviv with Philippe Sands, Sofia Dyak and Marina Chernivsky.

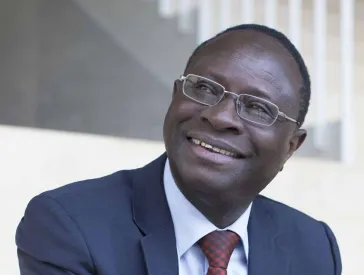

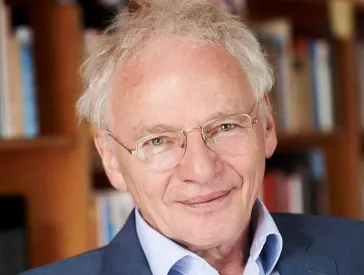

Marina Chernivsky; photo: Benjamin Jenak, Veto Magazin

Ukraine in Context: Discussion Series

Ukraine in Context: Lviv

With Philippe Sands (expert in international law), Sofia Dyak (Center for Urban History in Lviv) und Marina Chernivsky (psychologist ), video recording from May 8, 2023

More about this event

Ukraine in Context: Dnipro

With Tetiana Portnova (historian), Anna Medvedovska (historian) und Oleg Rostovtsev (journalist and leader of the Dniprov Jewish Community), video recording from March 2, 2023 (in German)

More about this event

Ukraine in Context: Odesa

With Mikhail Rashkovetsky (curator and art historian), Anna Misyuk (curator) und Nikolay Karabinovych (artist and musician), video recording from 19 January 19, 2023 (in German)

More about this event

Ukraine in Context: Chernivtsi

With Mykola Kuschnir (Director of the Chernivtsi Museum of the History and Culture of Bukovinian Jews), Oxana Matiychuk (author) und Petro Rychlo (literary scholar), video recording from November 24, 2022 (in German)

More about this event

Glückel in the Bowl

Glückel is confused: "Wasn’t Easter last week?"

Well, yes and no! Orthodox Easter actually takes place one week later. Glückel joins Ukrainian families — including those with deeper German roots, as well as recent refugees — to bake Paska, a sweet bread eaten during Easter. It's not a coincidence that "Paska" sounds like "Passover," a Jewish holiday. The colorfully decorated Paska will receive a blessing from the priest; for this, Glückel accompanies her new friends to the Ukrainian church.

Paska Recipe

Ingredients

- 750ml milk

- 1/2 glass oil

- 2 kg flour

- 3 packets of dry yeast

- 150g raisins or dried cranberries

- 250g butter

- 300 g sugar

- 2 packets vanilla sugar

- 8 eggs

- 400g powdered sugar

- Colorful sprinkles and other decorations

- Paska molds

Directions

- Combine milk, yeast, 3 tbsp. sugar, 5 tbsp. flour, and yeast mixture and let rise for 20 minutes.

- Combine melted butter, eggs, sugar, vanilla sugar, cranberries, raisins, flour, and yeast mixture and let ferment for 30 minutes.

- Knead vigorously and let ferment again for 15 minutes.

- Fill the molds with the finished dough and bake in a preheated oven (180 degrees C) for about 30 minutes.

- Beat egg whites with 400g powdered sugar until foam forms, and spread over the cooled buns. Then decorate as desired.

Happy Easter! — щасливого Великодня!

The Lavarello family of Berlin-Wilmersdorf shows Glückel how to celebrate Easter in Italian — and the little blue goat is amazed at all the connections to the Jewish holiday of Passover. The cake is shaped like a dove, a symbol of peace – something that the world needs now. The Colomba di Pasqua cake represents not only the Holy Spirit, but also reconciliation and happiness!

Colomba di Pasqua recipe

Ingredients for the dough

- Colomba cake mold (750g)

- 6 eggs

- 200 g sugar

- 100g butter

- 1 orange

- 1 lemon

- 60g almonds

- 60g candied oranges

- 350g flour

- 150g milk

- 1 packet baking powder

- 50 g Amaretto di Saronno

Topping

- 100g granulated sugar

- 100g whole peeled almonds

Directions

Beat egg whites and let sit in the refrigerator. In a bowl, combine remaining ingredients and then carefully fold in the beaten egg whites. Then pour the batter into the Colomba cake mold.

Decorate, then bake in a preheated oven at 170°C for 50 minutes. Let cool before serving.

Buon appetito! Buona Pasqua!

This week, Glückel joins the Zuckermann family at Alexanderplatz. Things are lively in the pious family's home, yet everything is in perfect order. Purim is just around the corner, and Rabbi Nathan is showing his children an Esther Scroll. While Glückel and the children dress up and act out the Purim story, Orit, the mom, is already kneading the dough for the hamantaschen. Soon, a sweet aroma permeates the Zuckermann home, and everyone sings cheerful Purim songs.

Hamantaschen recipe

Ingredients for the dough

- 4 cups flour

- 1 cup sugar

- 1/3 cup oil

- 1/2 cups orange juice

- 100 g butter or margarine

- 4 eggs

- 1 packet baking powder

- 1 packet vanilla sugar

Fillings

- Poppy seed paste

- Plum butter

- Jam

- Nougat cream

Directions

Preheat oven to 190°C. In a bowl, combine dough ingredients and knead until smooth. Let dough sit in the fridge for 30 minutes. Then thinly roll the dough and cut out circles. Spoon 1 tsp. of filling onto each of the dough circles. Pinch three sides together to form a triangle. Bake the pastries at 190°C for 15 minutes until golden brown. Enjoy!

In our third episode, little Jewish Glückel visits the home of the Yang family as they’re about to start making jiaozi! These Chinese dumplings have many names, and are the Yang family’s favorite dish. On the Chinese New Year, the Yangs decorate their door with the Chinese character for "luck" — and as luck would have it, Glückel lands on their doorstep! The Yang family quickly warms to the blue goat. While Glückel and the Yang family discuss Chinese food and Jewish food rules, the jiaozi steam in the bamboo baskets. To celebrate the day, the children receive gifts of money. Glückel doesn’t leave empty-handed, either.

Jiaozi recipe

- Ingredients for the dough: 700g flour, 300–350ml water, 3–5 g salt

- Ingredients for the filling: 500g Chinese cabbage, 5 eggs, 5 shiitake mushrooms, 8–10 spring onions, 1 tsp sesame oil, 2 tsp canola oil, 3 tbsp soy sauce, 2 tsp five-spice powder, 1 tsp pepper, pinch of salt

For the filling: fry the eggs in a wok and break them into pieces, then mix them with the chopped shiitake mushrooms, spring onions, cabbage, spices, and oils.

For the dough: knead flour, water, and salt into dough. Using your hands, roll dough into balls. Then roll them flat with a rolling pin. Place filling in center of each dough circle and seal to form jiaozi.

Steam jiaozi in bamboo baskets for 12 minutes. Serve jiaozi with a variety of dips.

Enjoy!

On the longest night of the year, Glückel lands in Berlin-Spandau, where Sulmaz and her guests are celebrating the Persian Yalda night. On this night, according to ancient beliefs, a battle rages between light and darkness. Surrounded by joyous revelers, Glückel bakes pomegranate coins with a deep-red color that is reminiscent of the sun’s glow. With candlelight and symbolic dishes, Glückel is pampered — and also learns about the fortune-telling tradition involving Hafez poems.

In her dish, Glückel flies from Tel Aviv to Berlin and lands in the Eliasson family kitchen. There, daughter Leah and dad Boris are making latkes for Hanukkah. Glückel helps prepare the Jewish potato pancakes, shedding a few tears while chopping onions. While lighting the Hanukkah candles, Glückel is subjected to a hug-attack from little brother Aaron, who only lets go of Glückel once the latkes are served.

Our Stories: Curators Showing Objects from the Core Exhibition

Our Stories: The Damaged Torah Wimpel with Aubrey Pomerance

The Catastrophe epoch room of the Jewish Museum Berlin’s new core exhibition includes an object that wears its tragic history on its sleeve: a Torah wimpel, or cloth binder, which was damaged during the destruction of the Worms Synagogue in the November pogroms of 1930 and exhibits conspicuous signs of fire. Archive director Aubrey Pomerance tells the object’s story and explains how it became part of the museum’s new core exhibition.

Jewish Museum Berlin, 2023

Our Stories: Alfred Benjmain with Ulrike Neuwirth

In 1942, a man’s body was discovered in the French Alps. In his coat pocket: a wallet containing photos and documents. Based on these, the man was the 31-year-old Alfred Benjamin of Germany. He had arrived France in 1934 on assignment for the now-banned German Communist Party and lived in Paris. Together with his wife Dora Schall, whom he had met in the Netherlands, he fought the Nazis as a member of the Resistance. Archivist Ulrike Neuwirth tells the couple’s story and explains how the wallet came to be in the Jewish Museum Berlin’s collection.

Jewish Museum Berlin, 2023

Our Stories: Entebee with Cilly Kugelmann

A postcard-sized work by the artist Boris Lurie: it features a white star on a yellow background, with the words “Judenknax,” “Fasanenstrasse – Synagoge,” and “Entebee”—what events does the work of art refer to? Cilly Kugelmann, head curator of the new core exhibition, tells the story of this small item in the exhibition and explains what makes it so valuable to the JMB collection.

Jewish Museum Berlin, 2020

Our Stories: The Ring with Miriam Goldmann

A tiny pewter ring with a menorah on it—it was found just twenty years ago in Kaiseraugst, Switzerland, but it dates to the 4th century. How did it arrive at its place of discovery and what does it tell us about the interwoven nature of Jewish and Christian culture? Miriam Goldmann, a curator for the core exhibition, tells the story of the oldest item in the new JMB core exhibition and explains why it is so valuable to the museum.

Jewish Museum Berlin, 2020

Our Stories: The Boxing Trophy with Leonore Maier

A small boxer made of bronze standing on a marble pedestal. His left arm is glued on, but its hand is missing—what does this object tell us about its owner and his life story? Leonore Maier, a curator of the new core exhibition, tells the moving story of Günter Loewinski, who survived the war in Berlin and rediscovered his boxing trophy in the ruins of his apartment building.

Jewish Museum Berlin, 2020

Our Stories: The Sweater with Tamar Lewinsky

A green and white knitted sweater and a photo of two sisters taken in a DP camp, in which one of them is wearing the sweater—what does this sweater tell us about the postwar era in Germany? Tamar Lewinsky, curator for contemporary history and for the new core exhibition of the Jewish Museum Berlin, tells a story of escape and persecution, new beginnings and memory.

Jewish Museum Berlin, 2020

Our Stories: Migration Objects with Theresia Ziehe

A compasses case, a child's painting, a kosher pan—what do these exhibition objects tell us about the migration experiences of Jews who came to Germany from the former Soviet Union? Theresia Ziehe, a curator of the new core exhibition at the Jewish Museum Berlin, talks about a daughter's longing gaze backwards and a woman's sense of connection to religious tradition in her family.

Jewish Museum Berlin, 2020

Our Stories: A Family Album with Aubrey Pomerance

Emigrate or wait and endure? In December 1936, to say farewell to his friends Erst and Margot Rosenthal, Bruno Heidenheim gave them an album: “Farewell, farewell, think of us oft, we'll send you our well-wishing thoughts. Happiness awaits across the sea, but saying goodbye to you isn't easy.”

Written and illustrated with an eye for detail, Heidenheim wanted to give his friends an “etiquette guide”

for America. Aubrey Pomerance, archive director and curator of the new core exhibition, talks about this testimony to a close friendship and two diverging life paths.

Jewish Museum Berlin, 2020

Our Stories: Fanny Lewald with Inka Bertz

A glimpse into a 19th-century work and living space : the cozy apartment belongs to the writer Fanny Lewald, who held a successful Berlin salon in her time. What does the image tell us about the inconspicuous-looking woman seated at the desk? Inka Bertz, director of the JMB collections and curator of the new core exhibition, tells the story of a luminary who fought for the emancipation of women and Jewish people.

Jewish Museum Berlin, 2020

Our Stories: The Flamenco Dress with Monika Flores

A white, purple, and pink flamenco dress, decorated with ribbons and heaped with ruffles. At first glance, there's nothing about this dress that one would generally associate with Jewishness. But it belonged to a Jewish person: Sylvin Rubinstein bought it, added certain details, and later wore it himself. Monika Flores, curator for the new core exhibition, tells the story of a distraught man who grieves his twin sister's death in his own way. Flores describes a Jewish object that reveals its identity upon close examination.

Jewish Museum Berlin, 2020

Story Time in Our Library: Read-Aloud Videos for Children Between 6 and 12

Malka reads Why Noah Chose the Dove. Text © 1974 by Isaac Bashevis Singer. Illustrations © 1974 by Eric Carle. Used by permission of Farrar Straus and Giroux Books for Young Readers. All Rights Reserved.

Ulrike Sonnemann and David Studniberg read Chanukkah-Büchlein (Little Book of Hanukkah) by Paul Hannemann and Heinz Wallenberg (in German and Hebrew) Take a closer look on the book! DFG-Viewer. Jewish Museum Berlin, 2020

Ulrike Sonnemann reads Der böse Gutsherr und die guten Tiere (The Story of Mrs Tubbs) by Hugh Lofting (in German) Take a closer look on the book! DFG-Viewer. Jewish Museum Berlin, 2020

Ulrike Sonnemann reads Fridolins Harlekinder (Fridolin's Harlequin Children) by My and illustrated by Walter Trier (in German) Take a closer look on the book! DFG-Viewer. Jewish Museum Berlin, 2020

Ulrike Sonnemann reads Evas Abenteuer (Eva's Adventures) by Hermine Hanel (in German) Take a closer look on the book! DFG-Viewer Jewish Museum Berlin, 2020

Ulrike Sonnemann reads Die Laubhütte im Himmel (The Sukkah in Heaven) by Ilse Herlinger (in German) Take a closer look on the book! DFG-Viewer. Jewish Museum Berlin, 2020

Lecture Series Kosher to Go (2021)

Holy Food and Drink – Why Do Dietary Rules Exist? With Prof. Kikuko Kashiwagi-Wetzel (Kansai University of Osaka) and Prof. David Kraemer (Jewish Theological Seminary of America), video recording from Thu 22 April 2021.

Read more

Kosher and Halal – Animal Slaughter in Judaism and Islam. With Aaron S. Gross (University of San Diego) and Serdar Kurnaz (Humboldt University of Berlin). Video recording from 19 May 2021.

Read more

Between Sanction and Sanctification – Alcohol in Judaism and Christianity. With Jordan D. Rosenblum (University of Wisconsin-Madison) and David Grumett (University of Edinburgh). Video recording from 22 June 2021.

Read more

Do you eat Insects? – Forbidden Animals In Judaism and Hinduism. With Dr. Syed (Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität in Munich) and Dr. Mattern (University of Tübingen). Video recording from 30 September 2021, in German.

Read more

The Kitchen as a Substitute Sanctuary? Modern Debates Around Eating. With Kathrin Burger (science journalist and author) and Jonathan Schorsch (Professor of Jewish Religious and Intellectual History at the University of Potsdam). Video recording available in German.

Read more

FOUR QUESTIONS by Yael Reuveny

FOUR QUESTIONS by Yael Reuveny Who are you?

Read More

FOUR QUESTIONS by Yael Reuveny What does it mean to be Jewish?

Read More

FOUR QUESTIONS by Yael Reuveny What is it like being Jewish in Germany?

Read More

FOUR QUESTIONS by Yael Reuveny Where is your home?

Read More

Hevrutah. Panels Accompanying the Exhibition Frédéric Brenner – ZERHEILT: HEALED TO PIECES

Hevrutah: Zerheilen – Healing to Pieces. Memory/Place

recorded on 6 Oct 2021

The first event in the “Hevrutah” (“Friendship”) series was on the topic of “Memory/Place.” Using works by Barbara Honigmann, Pierre Nora and Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi, Yemima Hadad, Netanel Olhoeft, Dekel Peretz, and Barbara Steiner, together with participants from the audience, discussed what a ‘memory of place’ is, how places are shaped by memory, and how the memory of places captures the imagination of the people living in them. The “Hevrutah” was moderated by Daniel Schönpflug.

Hevrutah: Zerheilen – Healing to Pieces. Otherness

recorded on 9 Dec 2021

The second event in the “Hevrutah” (“Friendship”) series was on the topic of “otherness.” Using poems and other short pieces, Liad Hussein Kantorowicz, Benyamin Reich, Irene Runge, and Adam Joachim Goldmann, together with participants from the audience, discussed how a self-perceived or an externally determined, ascribed otherness shapes a society’s view of that society, and whether this view necessitates a particular kind of responsibility. The “Hevrutah” was moderated by Daniel Schönpflug.

Hevrutah: Zerheilen– Healing to Peaces. Homeland/Diaspora

recorded on 16 Feb 2022

The third event in the series explored the subject of “homeland/Diaspora.” Using short texts and images from the exhibition Frédéric Brenner – ZERHEILT: HEALED TO PIECES, Akiva Weingarten, Sonia Simmenauer, Elad Lapidot, and Aviva Ronnefeld, together with members of the audience, discussed the confluence of “homeland” and “Diaspora” that so often characterizes Jewish lives. What constructive tension emerges from this confluence? What shadows does it cast? The hevrutah was moderated by Ofer Waldmann.

Lecture Series The Others’ Faith (2019/20)

See also our overview of all previous lecture series with video recordings

On the Path to Enlightenment: Judaism, Islam, and Buddhism

Whereas Jews rarely came in contact with the teachings of Buddha before the nineteenth century, the spread of Islam in central and southeast Asia sparked an intensive exchange between Muslims and Buddhists. What shape did these relationships take?

Today, the popularity of Buddhism is growing in the West. Its followers include a group known as JuBus: predominantly American Jews who have adopted Buddhist practices. What explains that interest? And how do Judaism and Islam today approach a tradition of thinking that recognizes deities but not one all-powerful and immortal God?

A discussion with Jerome Gellman (Ben-Gurion University) and Johan Elverskog (Southern Methodist University), video recording of the event on 24 Sep 2020, in English

Read more

Tying the Knot versus Bonds with God: Jews and Muslims in Interfaith Marriages

Does interfaith marital bliss require religious relativism?

Love goes beyond religious and cultural barriers, or at least that is what many believe. The growing number of interfaith marriages in Europe and the United States does seem to confirm this. But in day-to-day life, couples who practice different faiths confront a variety of challenges.

How do Jews and Muslims handle this? How can someone strike a balance between their own religious beliefs and their partner’s – and pass on those beliefs to children? And finally, how do the religious authorities react to interdenominational marriages?

With Madeleine Dreyfus (cultural anthropologist and psychoanalyst) and Imen Gallala-Arndt (Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology), video recording of the event on 18 Jun 2020, in German

Read more

Non-Transcendental Morality: Judaism, Islam, and Atheism.

Can mindsets critical of religion be constructive for a Jewish and Islamic theology that speaks to our times?

Skepticism, non-belief, and doubt have accompanied religions since their beginnings. As a result of advancing secularization, however, atheistic and agnostic convictions have become widespread in the Western world to an unprecedented level. How do Judaism and Islam respond to this?

As monotheistic religions, they both see the negation of God as a rejection of moral values. But do moral principles necessarily require recourse to transcendence? And how do Judaism and Islam meet the claim of rationality and reason formulated by the atheists?

With Jacques Berlinerblau (Georgetown University) and Ufuk Topkara (Johns Hopkins University), video recording of the event on 20 Apr 2020, in German and English

Read more

What do you think about Jesus? Judaism, Islam, and Christianity

Jewish and Muslim perspectives on Christianity – Many Christian beliefs and religious practices are baffling to Jews and Muslims, from the Holy Trinity and the veneration of saints to the role of Jesus as the Son of God. By contrast, the other two traditions applaud Christianity’s shared beliefs in divine creation and the immortality of the soul as well as the observance of moral principles.

Where do Jewish and Muslim perspectives on Christianity overlap? Where do they diverge? And how is the diversity of Christian denominations addressed in theological debates?

With Israel Yuval (Hebrew University in Jerusalem) and Maha El Kaisy-Friemuth (Friedrich Alexander University of Erlangen-Nuremberg), video recording of the event on 18 Feb 2020, in German and English

Read more

Mono or Poly? Judaism, Islam, and Hinduism