Intense Encounters in “Jerusalem”

How school children react to the tour through the exhibition Welcome to Jerusalem. A conversation with Marc Wrasse.

You’ve worked for the Jewish Museum Berlin for many years, as well as for other museums. What makes this exhibition special?

The Jewish Museum Berlin has a wide variety of visitors—the audience here is nearly as diverse as the modern world itself. If you visit the museum or work here, you can have a lot of different experiences, including in experimental exhibitions such as Obedience. Due to their social and political significance, I always find encounters during tours through Welcome to Jerusalem to be something special. Muslim students in particular—and that label encompasses much variety, ranging from the third-generation Turkish people in Germany to Syrian war refugees with their anti-Israeli background—are highly attentive in this exhibition.

X

X

Campaign for the exhibition Welcome to Jerusalem; Jewish Museum Berlin, designed by: Preuss und Preuss GmbH

View of the central exhibition room “The Holy City” with excerpts of the documentary 24h Jerusalem; Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Yves Sucksdorff

Why is that, in your opinion?

Most exhibitions are about a story or a topic. Welcome to Jerusalem is about a city. The exhibition doesn’t show our audience the country to which this city belongs, not Israel, not Palestine, but rather just Jerusalem—the significance and the fate of this city. However, the strong presence of the film 24h Jerusalem makes it clear from the beginning that it is about the present in this city and not its history. And its present is controversial. Everyone knows that.

What view does the exhibition take of Jerusalem?

If we think of the long history of Jerusalem as a huge mountain, then this exhibition doesn’t tear down the mountain, nor does it present its various kinds of stone, neatly sorted and arranged. Instead, it bores tunnels of various lengths and depths into this enormous mountain of memory. In doing so, it brings various jewels to light, which are displayed but not systematized and also not appraised. They are simply presented. Depending on who views them and how the light falls on them, how we as guides illuminate them and turn them this way and that on our tours, different aspects become apparent. However, it’s always clear: these are stones from the same mountain, the holy city of Jerusalem. All of its stones shimmer ambiguously.

From the beginning, the exhibition also shows Jerusalem as a place of longing in Christian memory. And so throughout, it maintains a kaleidoscopic perspective: from one room to the next, the lenses rotate through Jewish, Christian, and Muslim viewpoints. All conclusive rights to ownership of the city are immediately relativized and questioned through the story of this exhibition. In every visit, it can’t be overlooked: this unique city always also belongs to others. The many differences and the unique plurality of Jerusalem’s history and significance can also be configured productively. It is an opportunity for religious traditions to coexist. But you can try to produce unambiguousness, as people have always tried to do. In the long term, that didn’t work out in the history of Jerusalem. The exhibition shows that too.

X

X

Campaign for the exhibition Welcome to Jerusalem; Jewish Museum Berlin, designed by: Preuss und Preuss GmbH

How does the Jewish Museum Berlin approach this ambiguity, in your opinion?

Ambiguously! The museum presents this history without tying it to an explicit demand—except that you should look at it. In my opinion, this exhibition does not deliver a message, but rather an attitude. You could say that every museum wants attention, an audience, resonance. The Jewish Museum Berlin wants to invite visitors to consider things beyond what they already know about Jerusalem, and then to comment upon this knowledge and to talk about what they see. In a certain sense, this fits with the Jewish tradition and its transmission.

If people don’t talk to each other in this exhibition, everyone simply sees what they want. The exhibition also gives its audience the freedom to do so. That is the price of its unusual, kaleidoscopic perspective. The missing connection to the history of the country, the lack of an overarching theme in general seems strange to visitors at first, but it also goads them on, opens things up, leads to searching, to questions. And so individual visitors always follow our guided tours, listen along, observe us. The exhibition opens people’s views of Jerusalem.

How does the exhibition fit into the context of the Jewish Museum overall?

Just as Libeskind’s architecture at the Jewish Museum Berlin portrays Jewish history in Germany as damaged, the exhibition Welcome to Jerusalem depicts Jerusalem’s Jewish history as a broken one. With the destruction of the temple 70 CE, a forced diaspora began from Jerusalem, which led to something new—rabbinical Judaism—that hasn’t yet ended and that doesn’t only call Jerusalem its home, but rather the temple, the Torah, and the expulsion. That appeals above all to those who have a history of displacement. Since the museum has always been conscious of its neighborhood in Kreuzberg, this exhibition also establishes special ties to the city, to contemporary Berlin.

In this room with the Second Temple, the Roman relief of the spoils taken from the temple depicted on the Arch of Titus, and the Torah roll with breastplate and Talmud, in fifteen minutes, 3,000 years of Jewish history become visible, and it suddenly becomes clear to visitors what diaspora means and why in the year 70 a social and political history began that determines European history to this day; Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Yves Sucksdorff.

What does that mean, concretely?

Because of this exhibition, people now visit the museum who previously never would have dreamed of finding something of themselves reflected in it. Christian majorities may be less surprised, although the origins of their own stories from biblical Judaism are always perplexing, as is the idea of Christian success as a late product of Roman imperial history. The exhibition also reminds us that Islam was a focus for Christianity since its inception, and both have the history of an enduring adjacency in Jerusalem. As with Judaism!

The exhibition is of pre-eminent importance in its effect on young people from Muslim families—most are Berliners or come with school trips to the capital—and on school children who are refugees and who come with schools or other educational institutions. Earlier exhibitions at our museum have also depicted Muslim traditions, for example Cherchez la femme. Wig, Burqa, Wimple. In the Jerusalem exhibition, Islam is visible as an obvious part of antique heritage that has shaped European history from the very beginning. Not only can young Muslim people learn something new—like in school or any lesson—they also discover something of their own, something they’ve known for a long time and that is familiar to them, something they have an intimate, familiar relationship to.

How do these students react to the exhibition?

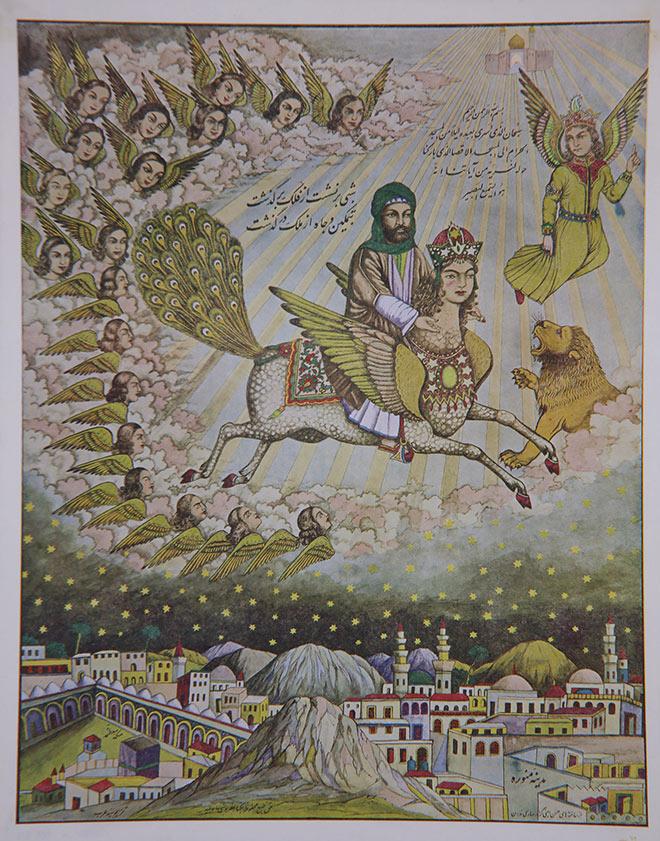

The Arabic script on the titular street sign immediately catches their attention. They visibly examine how this museum portrays history—the history of their religion. The presence of the Muslim tradition in the exhibition always causes confusion in young Muslim people because it becomes clear to them how little they themselves know about this tradition when they’re questioned more closely about the things standing or hanging there. Then they discuss amongst themselves. Some things they shake their head at, for example the image of the Prophet Muhammad from Iran, because the Prophet is not usually depicted. They like it and nod knowingly when they can identify the script or the angel or the lion on this image. When they see how precious the items on display are, they’re surprised, and they start to ask questions and to explain things. They talk in and with this museum—that is, with the people who do educational work in the exhibition for this museum—with real curiosity and with an often surprising urge to tell.

X

X

The street sign “Welcome to Jerusalem” over the museum entrance; Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Jule Roehr

Can you describe more precisely this reaction to you and what you are communicating?

They are attentive, critical, and at first they just listen. Most of what they see is unknown to them. More than three thousand years of history! When you ask, they answer. And they believe our answers: because references to the Prophet Muhammad area also hanging on the wall, and an unusual image of the Sultan Saladin, who was a Kurd, and in the same room is the Temple Mount with its contemporary buildings and many images of Jerusalem showing the golden cupola of the Dome of the Rock. They believe our answers because everything is there, and in context with the Western Wall, and the room on the Second Temple makes history visible as a series of events that haven’t been chosen selectively. For many of the young people, it corresponds to their own experience. They believe what we say because it’s visible in the exhibition, but it doesn’t make a claim to be a dominant, hegemonic story. Instead in every room something different appears, something surprising and presented in a surprisingly different way.

X

X

Ascension of Muhammad, Sayyid Arab, Teheran, ca. 1940–1960, lithography; copyright: Collection Puin

What’s more, on our tours, religion is presented as history, and history as an encounter with religious utopias, received traditions, and claims to representation. If you do educational work in this exhibition, you see people speaking with each other who otherwise wouldn’t speak to each other much. They’re curious, approachable, open. For students from non-Muslim families, the strong reaction of their Muslim fellow students is fascinating. They’re impressed at learning something historical about the Muslim tradition in the context of Jewish and Christian traditions.

How would you summarize your impressions?

For all students, visiting this exhibition is something new, and everyone can sense that they are experiencing this new something together. That certainly has a lasting impact, when the discussion is continued elsewhere. And so it would be interesting to hear from teachers whether this intensity only flares up as a mutual appreciation for a moment, or if it sets something in motion. But the fact that these conversations happen at all is thanks to the unique nature of the story called Welcome to Jerusalem.

Marc Wrasse lived and studied in Jerusalem in 1993/94. He works with museum pedagogy in various contexts and he designed two exhibitions at the Jewish Museum Augsburg as a guest curator.

X

X

Campaign for the exhibition Welcome to Jerusalem; Jewish Museum Berlin, designed by: Preuss und Preuss GmbH

Citation recommendation:

Marc Wrasse (2019), Intense Encounters in “Jerusalem”.

URL: www.jmberlin.de/en/node/6435

Behind the Scenes: Entries on the Exhibition “Welcome to Jerusalem” (9)

Firsthand Stories: A Tour of Tour Experiences (5)