A Mirror with Memory

Daguerreotype of Pauline Stern, Breslau, 1849, gift of Dr. phil. Fortunatus Schnyder-Rubensohn, 2016

Working with original objects is a main tasks of conservators. They analyze the condition of the objects and assess what treatments are necessary. Does the object need to be cleaned or flattened? What is the optimal storage method? The goal is to maintain the condition of the object long term. The collections of the Jewish Museum Berlin contain some daguerreotypes. One special one is that of Pauline Stern, taken in Breslau (today Wrocław, Poland) in 1849. Stephan Lohrengel, a paper conservator, shared with us some of his knowledge about this early photographic method, about Pauline Stern, and about the donation of this daguerreotype in 2016.

Did you restore the daguerreotype by Pauline Stern?

We have not yet carried out any treatment on this daguerreotype since it is in very good condition for being more than 170 years old. In particular regarding daguerreotypes, which are very sensitive, I first determine if any measures are necessary, in order to avoid possible later damage.

Why are daguerreotypes so sensitive?

The silver surface of daguerreotypes is extremely sensitive to touch and must be protected from the air to prevent it from oxidizing and tarnishing. That’s why they are all behind glass. For me that means if I do anything with them, I have to know precisely what. Since I am not a daguerreotype specialist, in such cases I always contact colleagues who are experts in the field.

What is a daguerreotype?

Daguerreotype was the first photographic process that went beyond merely experimental status and became widely used. The process was named after Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre, the Frenchman who developed it to the point that it was of practical use. He patented the process.

The process

- 1. In this process, the daguerreotypist polishes a silver-plated copper sheet to a mirror finish.

- 2. This is then treated with iodine, bromine, and chlorine vapors. The composition can vary. This forms a thin layer of light-sensitive silver iodide or silver bromide.

- 3. The photographer exposes the light-sensitive sheet for several seconds with a camera. The subjects cannot move during this time or else the picture will be blurry. On the exposed areas the silver iodide, or silver bromide, is transformed back to silver.

- 4. The exposed sheet is developed over hot mercury vapors. On the exposed areas the silver binds with the mercury to form a stable, matt mercury amalgam.

- 5. The sheet is then washed to remove all remnants of the unexposed silver iodide or silver bromide. These areas have a silvery shimmer. Various chemicals serve to fix the image.

- 6. Through the interplay of the different matt and reflecting areas and the incident angle of the light, the detailed image becomes visible.

- 7. In order to protect the surface from touch and air, the photographer mounts the finished daguerreotype in a frame behind glass or in a leather-covered case.

How and why did this process gain popularity?

In 1839, the French government acquired the rights to the patent and made it available at no charge throughout the world. Within months the process circulated worldwide. This is why 1839 is considered the birth of photography. Many daguerreotypes were produced up to the late 1850s.

Why did people have portraits of themselves made with this process?

The daguerreotype was the first process that made it possible to create a realistic depiction of people, albeit as a mirror image. It was also affordable for people who could not afford a portrait artist. This “mirror with memory” made it possible for grandchildren to see what their grandparents looked like as newlyweds.

What is special about a daguerreotype?

Each daguerreotype is unique. The process shows an unsurpassed sharpness of detail that is easily on a par with today’s image resolutions. The first paper prints were much grainier. Another feature of daguerreotypes are the reflecting areas. The image changes depending on the angle, shimmering between a mirror reflection and the motif.

Daguerreotype of Pauline Stern, taken in 1849; Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Roman März, accession 2016/287/2, gift of Dr. phil. Fortunatus Schnyder-Rubensohn

Why didn’t the process become widely accepted?

In the late 1850s, the negative-positive process asserted itself more and more. This process made it possible to make any number of prints of the photograph. Paper prints could be developed more quickly, much less expensive, and did not have to be carefully stored and protecting with cases or frames.

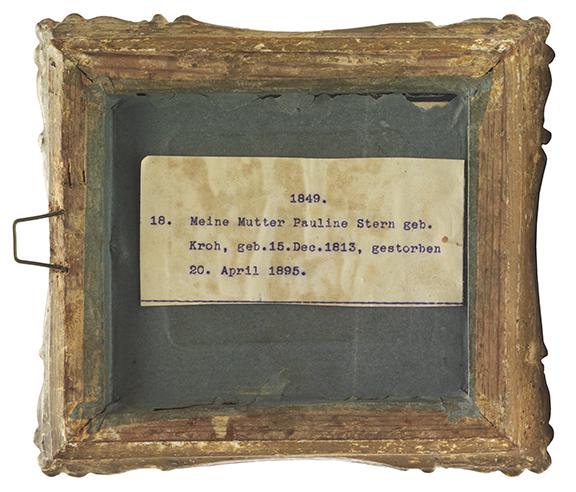

Written in German on the back of this daguerreotype is “1849. 18. My mother Pauline Stern, née Kroh, born 15 Dec. 1813, died 20 April 1895.” What can this inscription tell us?

For one thing, we know who is pictured. This information is not always written on the back of photographs. For the person portrayed, as well as the children and grandchildren, it was clear who this was a picture of. But for us it would be difficult to determine this information. The inscription also revealed to us that the daguerreotype remained in the family of the donor and had been passed down.

What do we know today about Pauline Stern?

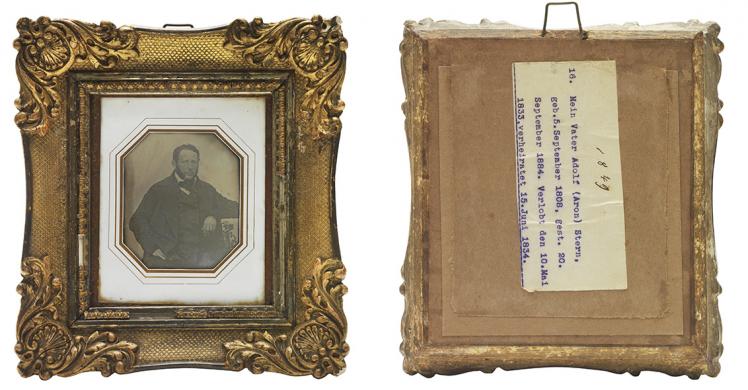

We know relatively little. Mostly what we know are her biographical dates: birth, engagement, wedding, death. Through address books we were able to determine that the Stern family lived in the Breslau city center. We also know that Pauline Stern’s husband, Adolf Stern, worked in the textile trade. Regarding the creation of the daguerreotype we can only speculate. Who took the photograph and when? Did they want their grandchildren to know what they looked like? Was it taken on the occasion of their 15th anniversary? What is special about the daguerreotype of Pauline Stern is that it has a counterpart: there is also a picture of her husband with an identical frame.

X

X

Back of the daguerreotype of Pauline Stern; Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Jens Ziehe, accession 2016/287/2, gift of Dr. phil. Fortunatus Schnyder-Rubensohn

The picture of Adolf Stern (1808–1884), like that of his wife Pauline Stern, was made in 1849, the heyday of daguerreotypes; Jüdisches Museum Berlin, photo: Jens Ziehe, accession 2016/287/1, gift of Dr. phil. Fortunatus Schnyder-Rubensohn

This daguerreotype was not donated to the Jewish Museum Berlin until 2016. Can we reconstruct the provenance over the years?

The two framed daguerreotypes were passed down over four generations from daughter to daughter. Most recently the portraits hung in Basel, Switzerland, in the home of our donor, Fortunatus Schnyder-Rubenssohn, evoking memories of the great-grandparents of his wife, Käte Schnyder-Rubenssohn.

How and why was it donated to us?

In 2006, the museum received the collection of the archaeologist Otto Rubensohn. Our donor Fortunatus Schnyder-Rubenssohn died in 2016 at the age of 101; in his will he stipulated that these objects be added to the Rubenssohn collection. The fact that the portraits were still hanging on the wall before they were donated shows that they were highly esteemed by the descendants. It is all the more moving for us when families decide to part with such objects.

What is the significance of the daguerreotypes for the collection in our museum?

Very few daguerreotypes are extant. This is due to the fact that they are so sensitive, on the one hand, and not everyone could afford one, on the other. Their good condition and the original seals make them very valuable to us, of course. We have only six other daguerreotypes in the collection and they are in much poorer condition. The daguerreotypes of Pauline and Adolf Stern are also among the earliest photographs of Jews in Breslau.

The interview was conducted by Immanuel Ayx, October 2021

Citation recommendation:

Immanuel Ayx (2021), A Mirror with Memory. Daguerreotype of Pauline Stern, Breslau, 1849, gift of Dr. phil. Fortunatus Schnyder-Rubensohn, 2016.

URL: www.jmberlin.de/en/node/8265

X

X