„Remember, remember ...“ – ein Tag im November

Über parallele Schichten historischer Ereignisse, die einander im Gedächtnis nicht tilgen sollten

Der 9. November war in England, wo ich aufwuchs, kein nationaler Gedenktag. Für uns galt:

„Gedenke, gedenke des 5. November, Pulver, Verschwörung, Verrat …“

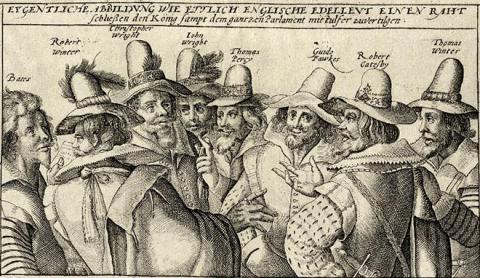

Der 5. November war das Datum, an dem Guy Fawkes, ein katholischer Renegat, spektakulär bei dem Versuch gescheitert war, das Parlament in London mit Schießpulver in die Luft zu sprengen. Seit über 400 Jahren hatte er seinen festen Platz im kulturellen Gedächtnis. Bei uns zu Hause jedoch blieb auch der 9. November nie unerwähnt. Er wurde immer mit Schaudern auf Deutsch kommentiert: „Kristallnacht“. Ein Ausdruck, für den es auf Englisch keine Entsprechung gibt.

Als ich 2001 nach Deutschland zog, stellte ich staunend fest, dass zum 9. November die organisierten Pogrome gegen Jüdinnen*Juden im Jahr 1938 tatsächlich ein Thema in den Medien und Gegenstand von Gedenkveranstaltungen waren. Es gab sogar eine Debatte zur Frage der angemessenen Terminologie: „Kristallnacht“ galt als zu poetisch, es spiele die Brutalität der Ereignisse herunter. „Reichskristallnacht“ erschien besser, weil darin anklang, dass die Verbrechen mit staatlicher Billigung und im ganzen Land begangen wurden. „Reichspogromnacht“ vermittelte einen präziseren Eindruck von der Gewalt und den Morden, um die es sich handelte. Aber sollte man nicht den Begriff „Nacht“ ganz infrage stellen, da sich die Pogrome über zwei volle Tage erstreckten? Solche Diskussionen waren mir fremd.

Am 9. November kommen in Deutschland einige historische Ereignisse zusammen, von der Novemberrevolution 1918 über den Hitler-Putsch 1923 und eben die Reichspogromnacht bis hin zum Fall der Berliner Mauer. Mir fiel auf, dass die Erinnerung an die Reichspogromnacht mit den Jahren in den Hintergrund rückte. Sie wurde überlagert von Erzählungen über den Mauerfall und das Ende der DDR, das nun, da ich diesen Text schreibe, auch schon 25 Jahre zurückliegt. Im Lauf einer Generation wurden Ereignisse von historischer Bedeutung durch jüngere Geschehnisse und Geschichts-Schichten ersetzt und verdeckt.

In der jüdischen Geschichte fallen die meisten nationalen Katastrophen auf ein bestimmtes Datum, den neunten Tag des hebräischen Monats Aw: Sei es die Zerstörung des Ersten und die des Zweiten Tempels in Jerusalem, die darauf folgende Verbannung der Jüdinnen*Juden aus dem Land Israel, oder seien es die Vertreibungen von Jüdinnen*Juden aus etlichen Ländern. Nach jüdischem Verständnis kann in der Erinnerung aber nicht ein jüngeres Ereignis die Stelle eines älteren einnehmen: Auch wenn sie viele Jahrhunderte auseinander liegen, koexistieren die Ereignisse im kulturellen und historischen Gedächtnis.

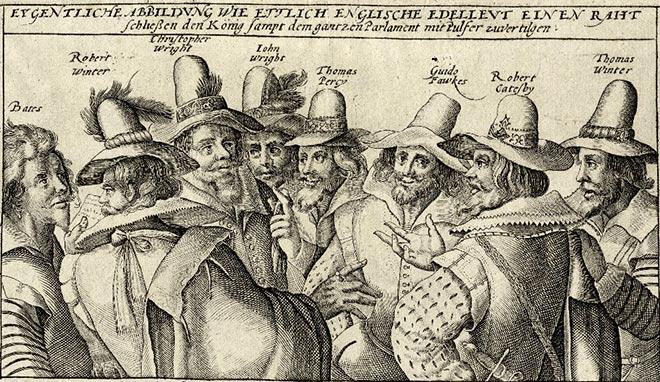

Die Pulververschwörung, Kupferstich ca. 1605-06; Quelle: Folger Shakespeare Library CC BY-SA 4.0

X

X

Die Pulververschwörung, Kupferstich ca. 1605-06; Quelle: Folger Shakespeare Library CC BY-SA 4.0

Welche Geschichtserinnerungen herrschen heute im Berliner Bezirk Lichtenberg vor? Im Jahr 1905 richteten jüdische Bewohner*innen in der Frankfurter Allee eine kleine Hinterhofsynagoge ein. Sie ließen dafür bunte Bleiglasfenster anfertigen. Eines dieser Fenster zeigte einen großen Davidstern und dazu, in hebräischer Inschrift, das Gründungsdatum der Synagoge.

Da die Lichtenberger Gemeinde gewachsen war, wechselte sie 1934 die Räumlichkeiten. Das Gebäude war nun keine Synagoge mehr, doch das Davidsternfenster blieb. In den 1940er Jahren zog die Evangelische Stadtmission dort ein, und zu DDR-Zeiten wurden die Fenster behutsam herausgelöst und auf dem Dachboden gelagert. Dort verstaubten sie jahrzehntelang. Wieder aufgefunden, wurde der komplette Fenstersatz im Jahr 2003 dem Jüdischen Museum Berlin gestiftet.

Es ist geradezu ein Wunder, dass das Fenster mit jüdischer Ikonografie in der Reichspogromnacht unversehrt blieb; soweit wir wissen, handelt es sich um den einzigen vollständig erhaltenen Satz von Bleiglas-Synagogenfenstern aus Berlin. Als stumme Zeuginnen der Geschichte künden sie von den wechselnden Verwendungen des Gebäudes, in dem heute ein belebter Indoor-Kinderspielplatz untergebracht ist.

Es muss möglich sein, dass wir die einzelnen und parallelen Schichten historischer Ereignisse im Gedächtnis bewahren, ohne dabei das länger Zurückliegende zu tilgen.

„Remember, remember the 5th of November, gunpowder, treason and plot; for there is a reason why gunpowder and treason should ne’er be forgot.“

(„Gedenke, gedenke des 5. November, Pulver, Verschwörung, Verrat; denn nicht ohne Grund sollen Pulver und Verrat uns unvergessen bleiben.“)

Michal Friedlander, Kuratorin für Judaica und Angewandte Kunst

X

X

Betsaal-Fenster mit Davidstern der Israelitischen Vereinigung von Lichtenberg u. Umgegend e.V. in der Frankfurter Allee, 1905; Jüdisches Museum Berlin, Schenkung vermittelt durch den Verein für Berliner Stadtmission

Zitierempfehlung:

Michal Friedlander (2014), „Remember, remember ...“ – ein Tag im November. Über parallele Schichten historischer Ereignisse, die einander im Gedächtnis nicht tilgen sollten.

URL: www.jmberlin.de/node/6553