“And next Sunday, no one will be thinking of the election anymore”

The 1930 German Federal Election

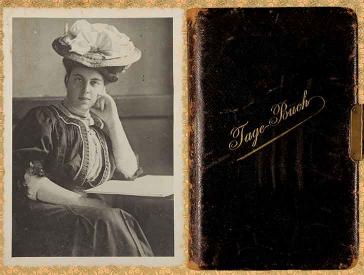

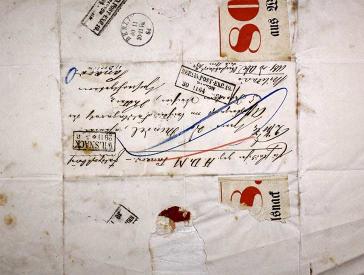

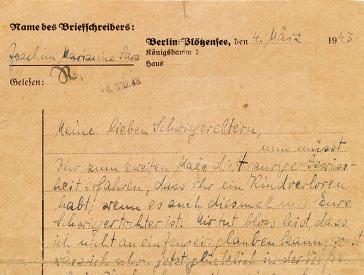

Recently I was leafing through the inventory listing of a family collection that has been in our archives for many years. I wanted to rework the index in order to bring it up to our current standards. The collection included documents, photographs, and objects from the Arzt and Bialostotzky families. In the twenty-three page inventory, a letter was listed for the Berlin liqueur manufacturer Heinz Arzt (1866–1931) in the category “correspondence,” but neither a sender nor recipient was listed, to say nothing of its contents. The extremely brief description went: “Letter: hand-written, 14 Sept. 1930.”

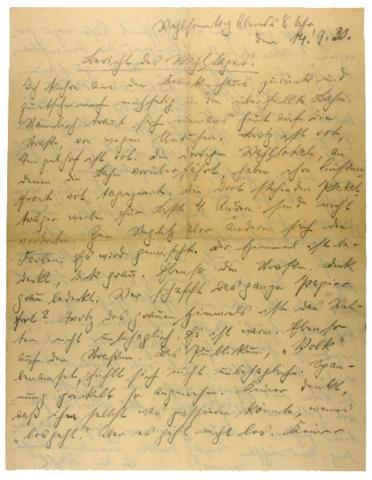

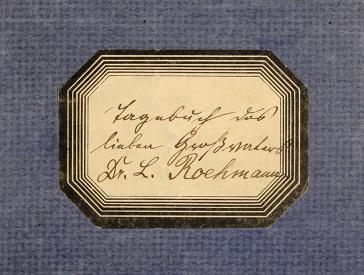

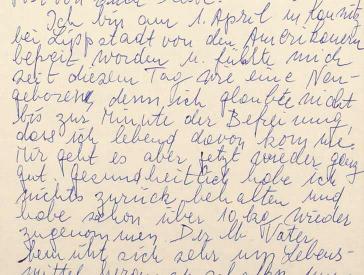

So I went into the archives and pulled the document numbered 2001/219/28 from box 451 to complete the listing. Suddenly, I was holding a fascinating piece of history in my hands: the so-called letter turned out to be a brief report on the 1930 Reichstag election.

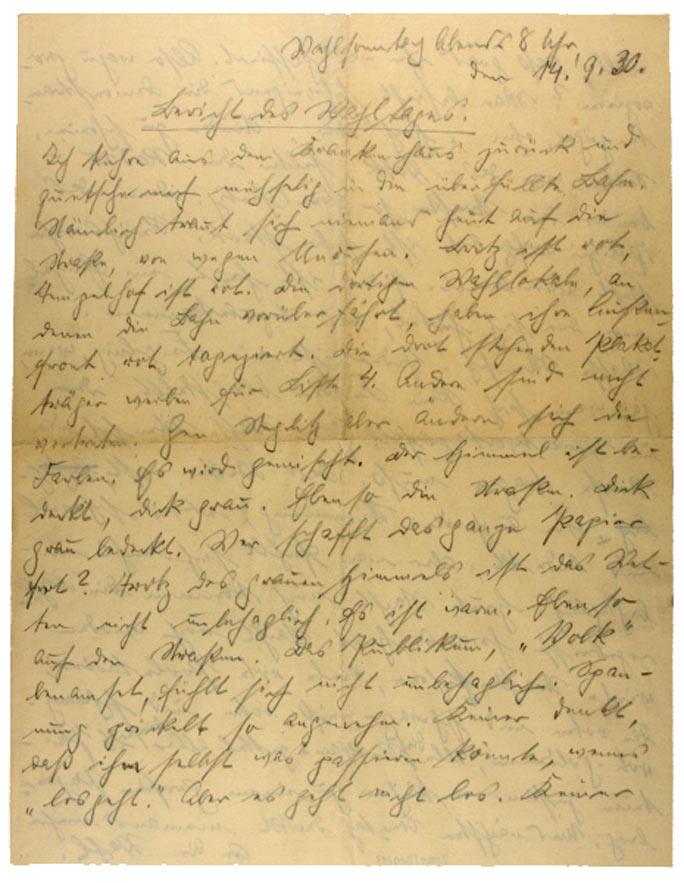

As I try to decipher the handwriting, outside Lindenstraße is plastered with posters for the current parliamentary elections—except for a short stretch directly in front of the museum. In the two-page text, the sixty-four-year-old Heinz Arzt recorded his observations on 14 September 1930 (on “election Sunday at eight in the evening”). He describes his tram ride through Berlin to his home on Steinmetzstraße, describing the prevailing mood.

“[I] struggle to squeeze myself into the overfilled tram. That’s because no one dares to go out on the street today, because of the unrest. Britz is red, Tempelhof is red. The polling places that the tram passes by there have their exteriors wallpapered in red. The people wearing sandwich boards there advertise for ticket 4.”

By which he means the Communist Party of Germany. The tram drives on.

X

X

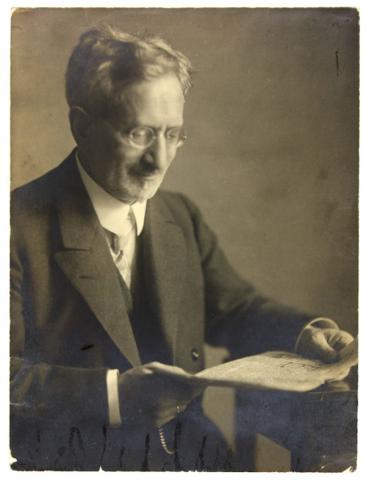

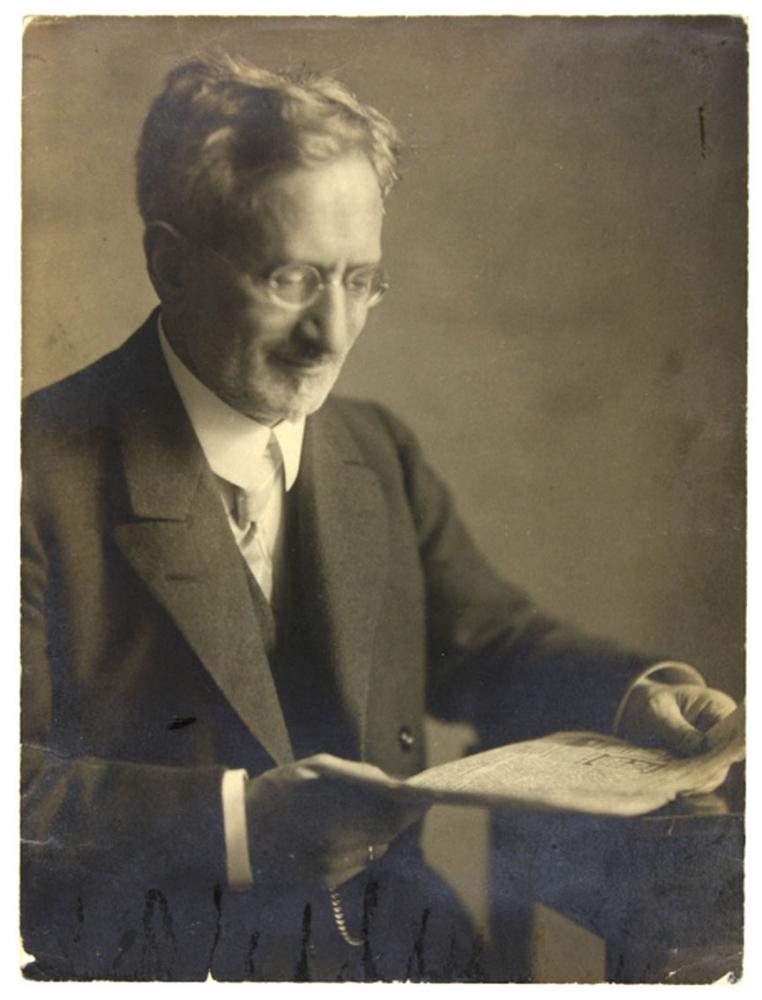

Heinz Arzt reading the newspaper, 1920; Jewish Museum Berlin, gift of Hilde Pearton, née Bialostotzky

“Toward Steglitz, the colors change. Things are mixed. It’s overcast, the sky is a thick gray. And so are the streets. Covered in thick gray. Who gets rid of all of that paper?”

asks Arzt looking at all of the election posters and fliers lying around in the streets.

“Tonight the election results will be announced. Tonight all of the street sweepers, many red proletarians, will heap together leaflets of all twenty-six parties—the red and black-white-red and black-red-gold—into a great mountain of paper.”

Arzt gives no hint as to which party he voted for, if he voted at all. The interesting thing about his enumeration, is that while he lists the colors of the communists (“red”), the anti-republican right who displayed the monarchist colors of the German Reich on their banners (“black-white-red”), and the parties who supported the Weimar Republic and were identified with “black-red-gold,” he doesn’t explicitly mention the National Socialists. Either he counts them in the black-white-red camp, since the swastika flag was also in these colors, or in his eyes the NSDAP was an insignificant splinter party. After all, in the last federal election in 1928, they only got 2.6 percent of the vote. Heinz Arzt concluded his observations with the words: “And next Sunday, no one will be thinking of the election anymore.”

X

X

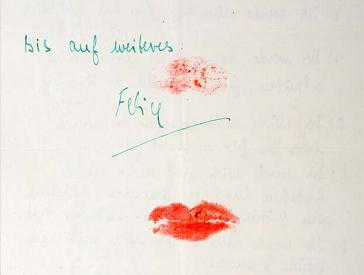

Text: “Report on Election Day,” by Heinz Arzt, Berlin, 14 Sept. 1930; Jewish Museum Berlin, gift of Hilde Pearton, née Bialostotzky, photo: Jörg Waßmer

In fact, the 1930 Reichstag election ended with a catastrophic defeat for democracy. The 1930 vote came about in the first place because the parliament repudiated a decree by Chancellor Heinrich Brüning. Brüning asked President Paul von Hindenburg to dissolve the parliament and call for new elections. This set a dangerous precedent for rule by decree, and the Weimar Republic found itself transitioning into a presidential regime, which would ultimately destroy it from above. Then on top of it all came a landslide victory for the National Socialists. They received 18.3 percent of the vote, their 107 representatives forming the second-largest faction in the newly elected Reichstag. The federal election was certainly not forgotten the next week as Arzt had predicted. It was momentous: at the constitutive session of parliament on 13 October 1930, all NSDAP representatives appeared dressed in the brown party uniform, violating the uniform ban that was in place. On the same day in Berlin, pogrom-type riots broke out. SA members beat and hurled antisemitic insults at passers-by, and the window displays of the Wertheim department store were destroyed.

Heinz Arzt didn’t live to see the National Socialists take power in 1933; he died in March 1931.

Jörg Waßmer, archive

Citation recommendation:

Jörg Waßmer (2017), “And next Sunday, no one will be thinking of the election anymore”. The 1930 German Federal Election.

URL: www.jmberlin.de/en/node/10614

Behind the Scenes: Anecdotes and Exciting Finds while Working with our Collections (22)