“No,

I Want Dr. O.”

I Want Dr. O.”

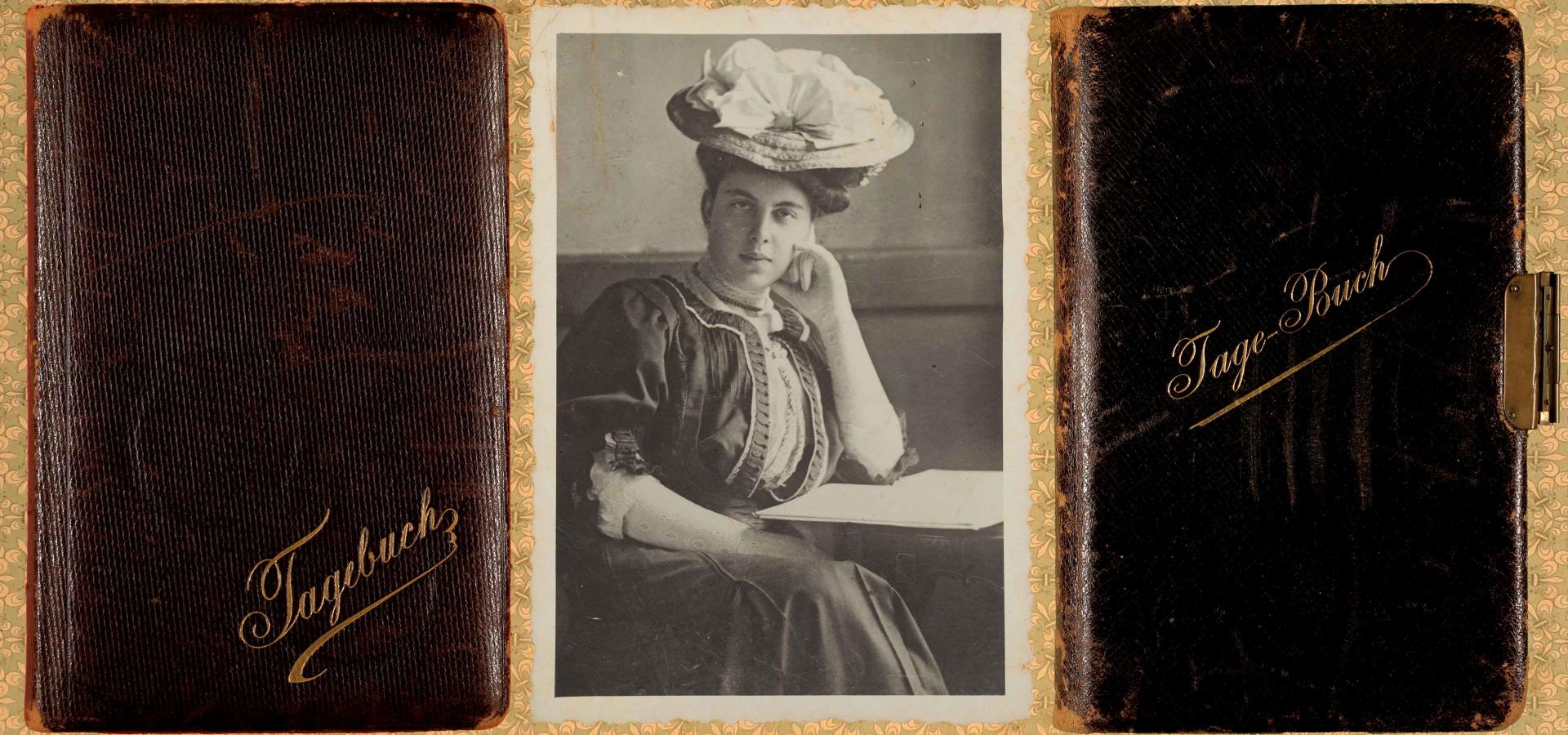

Leonie Meyer’s Diaries from the Years before her Marriage (1910–12)

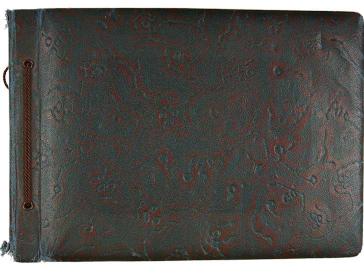

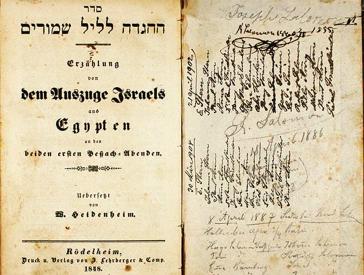

The German word for diary (literally “book of days”) is written on the cover of the slim little book. The gilded letters are just as shiny as ever. Apart from that, the wear and tear of time is unmistakable. Indeed, the diary is more than 100 years old and traveled quite a bit around the world before arriving at our archive in 2016 as part of an extensive family collection, to be preserved here for future generations and made accessible to researchers and the interested public.

The leather cover is battered. The lock, which once guarded the diary from prying eyes, is damaged and has long stopped serving its function. And so we can peruse everything that was confided in the diary during the years from 1910 to 1912, and get some insight into the life of its original owner, Leonie Meyer (1887–1948).

Leonie Meyer kept a diary for many years, not daily but at regular intervals. Only some of the entries are dated. There are a total of seven surviving volumes, which span a period of 27 years and trace her progression from a teenager to a 41-year-old woman.

She did not write the diaries for the purpose of future publication. Their contents are private in nature, but at the same time of general historic interest. Especially in the fifth volume, she reflects with remarkable frankness on herself and her situation, partly in comparison to her female peers. She describes her travels and her diverse hobbies, but also her relationships with various female friends. She uses her diary to contemplate her desires and expectations of a future husband. She struggles over which criteria should guide her in this life decision. It deals with subjects such as (falling in) love and desire; gender roles, including sexuality within and before marriage (and divergent standards for men and women); how to weigh up concepts such as marriages out of love versus prudence and/or arranged marriages.

What did a young, unmarried Jewish woman from an upper-class family think about these questions in the early 20th century? How does she perceive her own role? Does she even come into conflict with the expectations placed on her by her parents or her social circles more generally? What strategies does she use to navigate this territory and perhaps even gain more agency? Our archivist Jörg Waßmer has taken a closer look at the fifth volume and compiled some of the most interesting passages. For the sake of privacy, we have decided to obscure the names of other individuals who are mentioned in the diary, although they are all long deceased.

X

X

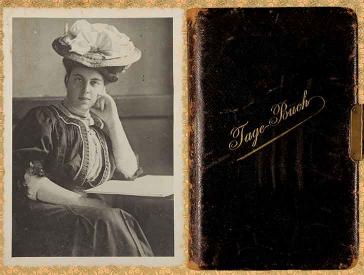

Leonie Meyer at home in Hanover, about 1905–1910; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2016/427/0, gift of the Oliven family

We will illustrate the diary entries with photographs from Leonie Meyer’s photo album that were taken around the same time. Not all the photos have captions, so not all the people in them could be identified; nevertheless, they give us glimpses of the lived reality of the young woman from Hanover. They also present a portrayal of women and men that usually, but not always, matches social expectations.

Born in 1887, Leonie Meyer grew up with her sister Edith (1888–1966), who was a year younger, in an upper-class Jewish family. Her parents were the prosperous private banker and councillor (Kommerzienrat) Emil Louis Meyer (1853–1926) and Helene Meyer, née Levy (1859–1942). The family was not particularly religious. In 1903, a 16-year-old Leonie wrote in her diary that she regretted not having been imparted a “love of religion,”

neither at school nor at home. At her house, the religion was “unfortunately... not kept up.”

The Meyers only attended synagogue on the Jewish High Holy Days. They also celebrated Christmas, including the practice of gift giving. They held patriotic views and venerated the German Kaiser. Accordingly, Leonie’s father showed little love for the Zionist movement, which aspired to a Jewish nation-state. All the same, there was no question for both Leonie and her parents that Leonie’s future husband had to be Jewish.

X

X

Leonie’s parents Emil Louis Meyer and Helene Meyer née Levy, 1907; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2016/427/0, gift of the Oliven family

For nine years, Leonie Meyer attended school in her hometown of Hanover. Shortly before graduating from the lyceum, she confided to her diary:

“I don’t have girlfriends, and I am also very unpopular, partly because I am always so horribly open and make such daft comments, and partly because they think I’m pretentious. All the girls at school are just middle-class, and if I just happen to talk about how this or that is done in our family, they immediately consider it inordinate pretentiousness.”

After graduating from the lyceum, she attended the Miss Hermine Wolff’s finishing school for young ladies in Wiesbaden from 1904 to 1905. There, she got to know (Jewish) girls who came from wealthy families in Germany and abroad; she developed close and lasting friendships with some of them. In January 1905, she moved back home with her parents in Hanover, where she pursued her wide-ranging interests. Meanwhile, she and her friends were expected, above all, to find a “good match” – that is, a husband – as quickly as possible.

X

X

The girls from Hermine Wolff’s finishing school, Wiesbaden, May 1904; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2016/427/0, gift of the Oliven family

On 2 May 1910, Leonie Meyer celebrated her 23rd birthday. Fittingly, a friend gave her a new diary as a gift to replace the previous one, which was full. Her first entry:

Diary Entry Dated 7 July 1910

“I thought I could begin this book with something besides the endless whining about marriage that makes me quite ill. Why are my parents, especially Papa, in such a rush? Certainly, they mean well and think that I would reproach them if they didn’t look out for me in this regard – but that’s silly, because I truly am not in such a rush, as long as they let me pursue my activities undisturbed. Because I am far from feeling ambition to marry before my girlfriends do, or any sense of envy or shame because I have so far been ‘passed over.’ I think that’s something felt by only those girls who have no opportunities, no assets or a very ugly appearance.”

~~~~~

More and more of her friends were getting engaged or married: “My birthday was a gathering of all brides,”

she wrote. Leonie thought her friend Lucie J., who was already a mother by then, had a “truly wonderful marriage.”

Relieved, she observed that her friendship had not suffered despite her friend’s marriage and baby.

In her free time, which she had in abundance, Leonie spent a lot of time riding horses, often in the company of “two officers’ fiancées.”

One day, when she got home from an excursion on horseback, she was notified that she would soon be introduced to a marriage suitor:

Diary Entry Dated 7 July 1910

“One afternoon when I returned home […], I heard that Papa would soon be arriving with a young man who was passing through for a lecture. I knew immediately that this was a certain Mr. M. from Frankfurt. I had once learned some information – his love life probably goes beyond the boundaries that are customary in his circles – about him and was very curious about the man. By all appearances, he is exceptional in terms of position, assets, family. Marie did tell me that he is very ugly, but aside from the nose, it wasn’t as bad as I had expected and he was a very chipper person, as best as I could tell in five minutes. Maybe I was blinded by the other attractive things, but in short, I would not have been averse to having a better look at him. But he disappeared in the dark of night. No one spoke of him anymore. When I finally brought him up, Papa’s response was vague; he felt that the man’s many interests in sports did not constitute any guarantee of a secure future. Perhaps he had not learned of the true reason for the man’s visit to Hanover or did not wish to know – because no one had said a word to him at home about the purpose, it would have been so difficult. I find this very understandable because otherwise I would not have understood how a young man such as he, who surely did not lack for suitable options, would go about looking for a wife in such a way.”

~~~~~

Not long after her meeting with Mr. M. from Frankfurt, Leonie Meyer traveled with her parents to Berlin for a short visit:

Diary Entry Dated 7 July 1910

“Now things get very nasty. Papa had previously asked me whether I wanted to meet a young practicing lawyer who was already bringing in 20–25,000 marks annually. He was said to be very nice and good-looking. At first I said no – these sorts of visits are torture for me. But Papa promised to handle the matter very discreetly, and not a word was exchanged on the subject after that.

[…] So in the evening, as we’re sitting at the table, a gentleman quite naturally shows up at our table, greets Papa like an old acquaintance, is introduced, and soon a very lively conversation is underway. It is true that at first I had the feeling that I didn’t want to marry him, he is so exactly the opposite of the type I like, although very elegant, good-looking, almost too polite with his “most gracious lady” and launching into all kinds of subjects. It seemed as though he could do anything (according to him). If the talk was of riding, he was an equestrian; of collecting ancient relics, he, too was a collector, etc. In any case the conversation was very animated, I was very lively and he appeared to like me surprisingly well. He was really delighted that this presumed marriage of convenience might perhaps provide him with such a sweet, lively wife. But things didn’t go the way he planned. Already by suppertime I knew to skillfully avoid any further dates with him. Upon leaving he kissed my hand so intensely that he got it quite wet, which disgusted me, and I had to furtively wipe it on my dress. That evening I didn’t breathe another word about him. The next morning at coffee, Mama suddenly and discreetly slipped away. At which point Papa said, ‘So, how did you like the gentleman? Would you like to get to know him better?’ He and Mama were almost convinced, since truly there was nothing to object to about him. So my answer came like a bolt from the blue: ‘No.’ ‘But why not?’ ‘He’s not my type.’ ‘Oh, come on, you need a better reason than that!’ ‘I don’t know any, only that I don’t like him!’ And I couldn’t be budged. Papa was beside himself; maybe someone else would have given in because I really didn’t have any good reasons.”

~~~~~

Privately, the 23-year-old had feelings for Fritz Oliven (1874–1956), a lawyer from Berlin 13 years older than her who had largely given up his trained profession and was mostly working as a writer. He had established a reputation as the author of humorous books published under the pseudonym Rideamus (Latin for “Let us laugh!”).

“I, however, was always silently thinking of Dr. Oliven, whose image I can’t get out of my head…”

Leonie had met him a year earlier during her summer vacation in the resort town of Marienbad, in western Bohemia (now Mariánské Lázně, Czechia). Let us return to the earlier volume of her diary, in which Leonie described the circumstances of their original meeting:

X

X

Book cover Berliner Bälle (Berlin Balls) by Rideamus (Fritz Oliven), illustration by Rolf Niczky (1881–1950), Schlesische Verlagsanstalt, Berlin, 1916; Jewish Museum Berlin, gift of Peter-Hannes Lehmann

Diary Entry Dated August 1909

“Mrs. Councillor F., who had also made Rena’s match... introduced us to all sorts of nice people. Especially Dr. Fritz Oliven... In Berlin, I’d already heard of his notorious impertinence, which made him hopeless for younger girls – but also the opposite, and that it very much depended on the younger girls in question – and was now astonished when I found him to be the finest fellow I have ever come across in my life. We had brilliant conversions – I have never seen someone so measured in conversation – the very best manners. – The polar opposite of Kätzchen [a nickname for a friend of hers named Katz] – leaving out anything erotic from conversation, never once an allusion or a slight double entendre. – During the first few days, I didn’t mention his books – he was too humble to do so. He wasn’t like Eugen or Dr. P., either, casually using a coarse word. He was an attorney, but he completely neglected that in favor of his poetizing – and here the anguish came out sometimes – he couldn’t write any verse or none of it succeeded, and because poetizing was his main profession, that was unfortunate! In general, I didn’t consider his talent anything phenomenal. A decent knack for rhyming, a gift of observation, witticisms – but indeed, not worthy of a serious man’s primary profession later in life. – I enjoyed conversing with him and did so often – and he wanted to marry me.”

Although Leonie also had feelings, she ultimately turned Fritz down:

“...on the last day, Edith, he and I went for a walk in the woods – and I realized that once again I had the difficult task of causing someone disappointment – but I’m in favor of keeping the table clean – no matter what, not stringing anyone along. The whole way, I laid the groundwork by talking about how hard it was for a decent thinking girl to turn men down – so that he wouldn’t think I had played fast and loose with him. Finally, he said he wanted to travel: ‘So you are staying until the 15th?’ ‘Yes.’ ‘So if I come on the 12th, I’ll still get to see you.’ – ‘I don’t think so.’ – He lowered his head; he understood. A very brief adieu, and in my dismay I forgot to wish him a pleasant journey and he left. The response was both illogical and stupid – but it said what I wanted.”

~~~~~

Marienbad, 1909

“First Time Meeting Fritz,”

from Leonie Meyer’s photo album, Marienbad, 1909; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2016/427/0, gift of the Oliven family

Leonie Meyer (right) with Alice P. and Fritz Oliven on a walk, Marienbad, 1909; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2016/145/427, gift of the Oliven family

That was the flashback.

Now we can return to the chronological narrative, which brings us back to the year 1910. Again, that year the Meyers spent their summer vacation in Marienbad.

“This time there were no young men in Marienbad, but we spent a delightful time with Alice P. and Bertha G. (engaged to Dr. M.).”

Leonie and her sister Edith passed the time playing tennis with Alice and Bertha. Leonie held both young women in high regard: In her description, Bertha was “a capricious little lady, with artistic tendencies, a bit pretentious, but full of character.”

Even though her fiancé was not particularly faithful, she understood “how to fasten the man to her with a thousand little feminine wiles.”

And Alice was “a splendid creature, for whom I wish the best of all men.”

“But I am afraid that they will exhaust Alice’s defenses with all the suitors they are parading before her. Just as with me, they don’t ‘force’ you, but rather ‘wear you down’ until your own will is quite weakened and you resign yourself.”

Leonie Meyer had more contemptuous words for other “girls”

:

“Rather than those silly geese with their flirting and their preening, I prefer the girls in whom you can already see traces of the future woman; not just creatures of luxury, but those who, even if they have no profession, engage with the ideas of the times, are aware of their personalities, and have a feminine understanding of their surroundings and its weaknesses.”

X

X

Leonie Meyer with a tennis racket, alongside her sister Edith on the right and her vacation acquaintance Bertha G. on the left. In front of them are two ball boys holding tennis balls, Marienbad, 1910; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2016/427/0, gift of the Oliven family

That year in Marienbad, Leonie Meyer met a young man from Düsseldorf, Hubert P., whose mother was a painter. Leonie felt drawn to him, but also worried that he could later grow “smug or become a bon vivant.”

She got a preview during a tête-à-tête one evening:

Diary Entry Dated July 1910

“One evening everyone had gone to the theater and he came over, […] sat in the big armchair, talking all kinds of nonsense about marriage and wives who by nature are predisposed to be faithful! While for a husband that was impossible!!! etc., and then, in between all that, kept calling me ‘dearie.’ And I could have really wanted to kiss him if I hadn’t been afraid of his triumphant expression afterwards.”

~~~~~

A man, presumably Hubert P., sitting casually on a bench, Marienbad, 1910; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2016/427/0, gift of the Oliven family

From Marienbad, the Meyers traveled onward to Hamburg, where they had been invited to her cousin Alice K.’s wedding. Leonie did not think much of her cousin’s new husband:

Diary Entry Dated 20–23 August 1910

“He is a dumb oaf who opens his mouth to eat, but really wide. He really put his foot in it, and is now enjoying the good life with comfortable expanse, lets Alice spoil him, gets the best bits on his plate, and aside from that doesn’t make the slightest effort with her parents and the rest of his new in-laws; he confines his courtesies to the minimum, since Alice sticks with him and he takes it far too much for granted. Aside from that he comes from a fully petit bourgeois background. Alice slobbers all over him.”

Apart from them, Leonie did not have a particularly good time at the wedding:

“At the wedding I was seated with a 50-year-old bachelor, who had already courted my mother and who had the reputation of a bon-vivant; I did not like him much, he was more of a type for married people.”

~~~~~

Back in Hanover, Leonie met up with her two good friends Lucie H. and Erna S. Both of them were soon to be married.

Diary Entry Dated August 1910

“For Erna, things may not be that easy; much will be different from her girlish dreams, and much about marriage still scares her. If it weren’t for cowardice, and if a broken engagement weren’t seen as such a horrible failure in our circles, I don’t know what would have happened.

Some of Ernst’s physicality scares her, she is very sensitive, something with which few men can sympathize. Although they make the first step easier – for certain moods they are often too tough. And for a young woman consciously approaching marriage, some thoughts are quite excruciating, and it is best not to think at all. Maybe if one is very much in love, one does not think so, but if one commits to a marriage of convenience, which may turn into a marriage of love through accommodation or habit, with a man to whom her senses attract her only because she is needy, not because she has a special attraction to him, then there are anxious moments, and where will that lead? But familiarity will come sure enough, and her wishes will drift off, the girlish dreams and ideals be forgotten, and a calm contentedness fill her life. Maybe she will be lonely at first in a big city without family or friends, and she may brood and cry a lot at the beginning.”

~~~~~

In September 1910, Leonie had several visitors. First came her friend Lene H. (“very happy and high-spirited, but with a hint of coquettishness”) and then Kurt and Rena, who were behaving themselves rather scandalously in her opinion:

“Kurt and Rena were here, locking lips to the point of unconsciousness, and Marie says that when they sat at the table, she could barely serve them because they’d be sitting so close together!”

Leonie Meyer riding her horse Lady, 1910; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2016/427/0, gift of the Oliven family

Then, in October 1910, Leonie Meyer traveled to Neustadt, Upper Silesia (now Prudnik, Poland) to visit her friend Alice P., with whom she’d had such a great time on her summer vacation. On Yom Kippur, the two friends went to synagogue together:

“With all the hecticness of the year, one day of contemplation is necessary!”

On the evening before her departure, Alice came to Leonie’s room and opened her heart:

Diary Entry Dated 12 November 1910

“[She] sat on my bed and wanted to say something but did not have the courage. Little Alice suffers from the same affliction as I do – her parents are searching for a groom. ‘We’ve already introduced her to so many this year, I do not know what she always objects to; it’s about time she put an end to it!’ Mrs. P. said to me impatiently […].

Just like my parents, she thinks that this sort of marriage is the only possible kind, the perfectly natural one. They cannot understand that a modern young woman would think any differently. And indeed Alice shares my thinking – we both hope to get someone we love, and no, not by that route. Just as I feared that Papa would intervene when it came Dr. O[liven], she too lives in a state of hopeful anticipation and doesn’t dare speak a word about the man she likes for fear of her parents’ lack of prudence. She paced around the room, agonizing over whether she should confide in me. I switched the light off entirely, she lay down next to me and confessed that it was Carl. I moved closer to her. She’s been fond of him since February, and if her mother had not decided on the sudden departure, there would have been a clarifying conversation. As it is, she has not heard from him for a long time. She questioned me a little in the summer – that was all. Then she showered me with questions. I said, ‘He seems to me like a decent person.’ ‘Tell me a little about his other qualities.’ ‘Well, that’s too subjective. What I think is nice, you won’t like, and vice versa. [...]’ ‘Does he run around a lot?’ ‘Like all of them, but he has the decency not to call attention to it – by the way, the ones who have let off some steam are not the worst.’”

~~~~~

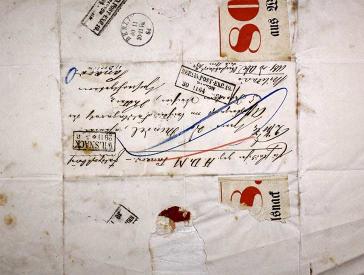

The following pages of the diary later fell victim to Leonie Meyer’s own self-censorship, or at least they were torn out by someone. But from the few fragmentary lines that have survived, it is clear that Leonie still had feelings for Fritz Oliven: “No, I want Dr. O[liven]!”

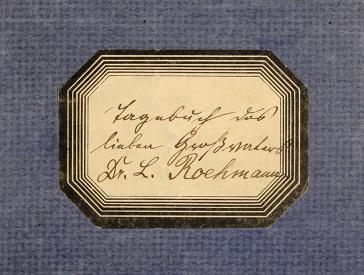

“No, I want Dr. O.!” excerpt from a diary entry from November 1910; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2016/145/636, gift of the Oliven Family

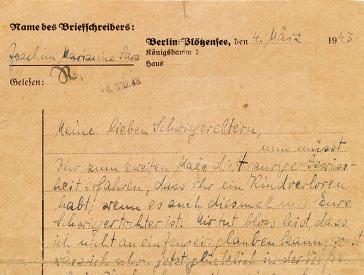

During a stay in Berlin, she takes the initiative herself and contacts his mother, Louise Oliven:

Diary Entry Dated 12 November 1910

“I contacted Frau Dr. [Fritz Oliven’s mother], although doing so felt brazen. She suggested a meeting on Monday at Schilling’s café. We talked about nothing important. I was on pins and needles. She invited me to the theater on Wednesday. I cannot possibly say how unspeakably brazen I felt and how mortified I was by the whole thing.”

~~~~~

There are no further pages on this topic. The next entry, dated three days later on 15 November 1910, explains that Leonie was now confined to her bed after tearing a tendon.

In the new year, Leonie met up again with her married friend Lucie H., who told her how unhappy and in fact violent their mutual friend Erna’s marriage had become:

Diary Entry Dated 2 January 1911

“Lucie told me about Erna’s marriage. Erna has no one to talk to in Hamburg, although her heart is overflowing. I completely understand why she confided in Erna and not me. It is easier to talk about these kinds of things among young women. Erna is expecting – first she felt quite ill and was lonely, and still had to constantly submit to Ernst. She is not angry with him, she says ‘he is a man,’ but she is miserable inside. On the first night of their honeymoon, he took her so fiercely that she cried out in pain, and trembled before every new night. And he was a man through and through, and had no empathy for her emotional suffering. When it was over, he slept soundly and gratified, while she lay awake all night brooding. Dry and joyless, because she had to submit without consideration of her mood, only fulfilling her wifely duty.

And until now she sees it as nothing but an annoying ‘duty,’ which disgusts her, and when she asked Ernst recently: ‘Well, if you had to do it all over again, would you still want to get married?’ He promptly replied ‘No.’ That is how agonizing her married life is.“

~~~~~

Three-part photo series of Lucie H. from Leonie Meyer’s photo album, 1907; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2016/427/0, gift of the Oliven family

Again Leonie traveled to Berlin, this time with her parents and sister. On their very first evening, they had plans to see an operetta, Die schöne Risette, followed by dinner at the Kaiserhof on Wilhelmplatz. But that was not the true reason for the trip.

Diary Entry Dated 11–16 January 1911

“This time I knew it was getting serious. Papa had something up his sleeve, and knew how to get me interested. Actually, he had wanted to make the introduction before Christmas, but I went on strike. On the first night, Die schöne Risette. I thought he would be there at the theater or at dinner afterwards at the Kaiserhof. I trembled, but he did not show up. Only much later, during coffee in the lobby, eventually a gentleman rose from a group of friends, greeted Papa, talked business with him for two minutes, and only dared cast me a brief sideways glance and barely spoke a word with me directly. He was embarrassed by the situation. So was I. Two days later he met us for tea, but again barely talked to me. Only on the last evening, at Hiller’s, where Edith was present as well, did we become more animated. But he seemed to like Edith better. She was less self-conscious, hence livelier and more natural. I can’t say I dislike him, but I don’t think he has much in the way of intellectual interests. I’m dreading the planned meeting in Schierke. Papa is so in love with him, I am tired of saying no, and even Mama has started making speeches whenever someone gets engaged.”

~~~~~

Soon after Leonie’s return to Hanover, her friend Alice P. came for a visit. She was now engaged to Karl, a relative of Leonie’s from Hanover who has just passed his exam as a court assessor. Alice was passing the time in Hanover, waiting to be introduced to his family. Leonie observed the new couple and concluded:

Diary Entry Dated 5 February 1911

“They were a very rational couple – almost too cool. No words of affection, no kissing whatsoever. Maybe she’ll defrost as a wife or already when she is in Neustadt – they are still strangers to each other and Alice is not the type to bare her thoughts and feelings immediately, and also tends to be critical and thinking. She expects life with Karl, who has so many interests, to be lovely. […] He will be good to her, but will she be happy? She is not the type to put up with anything while intoxicated with love. I hope she will not be too lonely here. (...)

[Karl] was a little shy toward her, lost his energy, did all she asked and treated her as a shrinking violet. He might prefer more tenderness, but he considers this the virtue of a pure young girl, whom he respects (he is a decent person). And since he only knows the amorous attentions of the ‘others,’ he believes that such reticent chastity comes naturally to an heiress apparent and tries to convince himself that this is something very honorable about Alice, so (at least during the engagement!) he lets her be. On the contrary, he is looking forward to her ‘awakening’!”

~~~~~

Following the news that Leonie’s friend Alice was engaged too, Leonie’s parents continue looking for a husband for her. In early March 1911, the family went on yet another trip with that in mind, this time to Wiesbaden.

Diary Entry Dated 2 March 1911

“Tomorrow it’s off to Wiesbaden. Dreary weather and it promises to be dismal. If the weather were conducive for a trip, then things would not be so stark and sad, it would be a vacation, and the meeting might feel casual. Instead it is a polite routine, the intention becomes noticeable and the mood is thrown off. But I will try to like him – there is no point in continually resisting and living in dreams – quietly, passively, I go wherever the current takes me – I knew it would come that way. I have removed the terms ‘love,’ ‘meeting of the minds,’ and ‘spiritual companionship’ from my expectations of marriage and decided to be happy without them – I have the will and I believe life will not defeat me. I believe that I will be strong enough to put up with everything, even if my husband does not participate in the life of my soul.”

~~~~~

Five days later, Leonie reported to her diary on their stay in Wiesbaden and her first meeting with a man there.

Diary Entry Dated 7 March 1911

“On Saturday morning, when Mama and I wanted to go out, Mr. M. crossed the hallway and joined us. In the afternoon we went to the Dietenmühle and in the evening we ate at the spa clubhouse. On, Sunday the two of us went for a walk in the forest; I told him about my girlfriends – in the afternoon we were in Biebrich, then at Blum’s café, where he showed his sweet tooth; before supper he came into my room for a moment, but Mama was sitting there writing a letter; then after supper we said ‘farewell’ without anything more – so he has his doubts, just as I do, as to where this will lead. If I had had the opportunity to speak frankly with him, I might have said the following: You have likely found me to be a girl you could live with, and I think the same of you. I like you, but I do not feel any more passionate love for you than you do for me. I am too critical a type to love you. You are a good-natured person, not stingy with money either. But a bit too much of a stockbroker – in your demeanor and way of speaking – and above all very materialistic in your thinking. My soul may starve a little living with you; you may not participate in my intellectual life.

[…] Mr. M. and I conversed as impersonally as I have ever talked to a young man with whom I spent so much time alone. We remain strangers to each other as much as on the first day, although he knows now that I am very intelligent and practical; and I know that he is kindhearted, loves children, and is a bit of a busybody. It should be possible to break him of his bad manners; he’s also a little overweight. Is there anything there? And what is he thinking? I think just as coldly as myself.”

~~~~~

Leonie Meyer playing golf with an unidentified man, about 1911; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2016/427/0, gift of the Oliven family

Two weeks later, Leonie and her family were finally back in Berlin. They attended a ball at the theater and Leonie enjoyed herself – despite expectations:

Diary Entry Dated 20 March 1911

“A very attractive young blond man stood behind me. I looked at him a bit, then away; I don’t like attracting someone with glances. He asked me to dance, and then it came time for the performance for which he brought me a chair. Afterwards we sat upstairs, where it was very fancy, like at a private home, and drank champagne. A friend of his joined us with his girl from Munich, who was also very refined among the ‘Kurfürstendamm’ set. He addressed me formally at first. As he said, he was too Northern German to be casual right away. […] He did not introduce himself, but he was a proper gentleman, cut up my roast beef sandwich and had kind but steely blue eyes. Papa and Mama were downstairs as well, but I acted as though they were not with me.”

Over the course of the evening, Leonie and her suitor got closer. Leonie successfully shook off her father, who had been acting as her chaperone. Her admirer insisted on escorting her home – and Leonie agreed after some initial hesitation.

“In the car, he embraced me. I defended myself because he searched my mouth, his tongue touched my lips and my tongue, and I found that a little unpleasant. (Not repulsive, as he was so appetizing and didn’t smoke.) ‘Like an operation,’ I said as I fended him off. He paused for a moment, then kissed me harder, his hands rushing along my thighs to reach under my dress. ‘You are unkind.’ He let go immediately. ‘I don’t want to be unkind. You are lucky that you wound up with me. But why don’t you want to give yourself? You have a hot temper, you little imp, give yourself. See, tomorrow you won’t have any regrets.’ (But the day after tomorrow, the consequences might rear their heads, I thought to myself.) ‘Why do you want to give yourself only in marriage? Do you think your husband will awaken your passion? See, I would like to whisper something in your ear: You will remember this little car trip even after many years of marriage.’ I was stupid enough to say, ‘Don’t be theatrical,’ which offended him, I think. And he was a decent person, because if a young girl allows herself to be kissed (and enjoys it, as he could tell) then she should not say anything if he loses track of his hands in the steamy heat of passion. It was marvelous that he stopped immediately. ‘Give me one last kiss on the lips.’ I did not want to, so he kissed me farewell. I would have loved to stay with him; I kept thinking of him for hours and thought that I should have let him kiss my neck and breasts. I was annoyed at myself that I had been too foolish again and did not enjoy myself enough. And how I should have let him kiss me! I would have given him everything where it not for the fear of consequences. There was no question of shame or of chaste fear in me at that moment! He must have been annoyed as well to have to stop in the middle. More annoying for a man than for a girl. I would have liked to tell him, by way of conciliation, that it hurt me to stop. For me marriage is not a matter of giving or gifts, only being taken, dutifully on the first day, whether in the mood or not, no celebration of love. But by then we had already arrived at the Kaiserhof, and much was left unsaid and unkissed.”

~~~~~

While the Meyers were still in Berlin, they received a visit from Mr. M., who had been presented to Leonie as a suitor in Wiesbaden.

Diary Entry Dated 6 May 1911

“[He] came over a few times, but just in passing and impersonal. Then to Papa. And told him that his late uncle had invested his entire fortune in a precarious deal. And he did not want to get married before that was sorted out. He hoped that would be soon… Now Papa was sad, because he liked the man. But he saw the matter as finished. Later I asked him. He said ‘One can’t throw one’s whole fortune after that. There is no point in thinking of it anymore.’ That annoyed me. Not because I had attached my heart to him – I was even glad about this solution – but because Papa sees me as trivial. First he introduces me, asks how I like him. ‘I’m not in love, but I could take him!’ Followed by Papa’s indignation that I’m so chilly. And then suddenly, because of this calamity, he considers it obvious that all is over and that the entire matter is swept aside without a word. What if my heart had been truly involved, as he’d wished? His way of treating this matter as over shows that he does not take my heart into account, so why this indignation when I honestly admitted that I would have only gone along with it for practicality’s sake? One cannot deal with love so roughly and then arbitrarily order ‘Stop’!”

~~~~~

In June 1911, Leonie was invited to another “eve-of-wedding party,”

which she found “boring”

even though she got to wear “a pink Liberty dress”

and was complimented that she “looked especially good, which Rudolf, who was a little tipsy, kept telling me.”

From 15 July to 13 August 1911, the Meyers spent their summer vacation in Marienbad, once again. By then, two years had passed since Leonie Meyer first met Fritz Oliven. Thoughts of him were still lingering in her mind.

“Mrs. Councillor F. told me that Dr. O[liven] still thought of me and wondered whether to come visit. I did not say yes, because I had slowly gotten used to the idea that nothing would come of it and I did not want to lose my cool again.”

To distract herself, she spent a lot of time with Mr. L., the business manager of a large bank. She was struck by him. After all, he was “handsome, tall and blond”

and she “had to get married eventually”;

besides, she was tired of all the “matchmaking.”

But Mr. L. had “a thousand worldly ideas”

and left town abruptly.

In September 1911, Leonie Meyer traveled to Berlin with her father. Mrs. Councillor F., who had introduced her to Fritz Oliven in Marienbad two years earlier, invited her to lunch. They went to Weinhaus Rheingold on Potsdamer Platz – and she had an unexpected reunion:

X

X

Fritz Oliven as a young man in a frock coat, studio portrait (J.C. Schaarwächter, photographer by royal appointment), 1900; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2016/147/18, gift of the Oliven family

Diary Entry Dated September 1911

“When I arrived at the Rheingold, Fritz Oliven appeared out of nowhere with the Councillors [F.]. And we were good friends again right away. I teased him with a grapefruit that he had ordered, and saw in him again the same overgrown boy as two years ago. Then he brought me to Becca’s and on the way we discussed life and disagreed on every point. He said that he was idle, just dallying on the sofa – I said I was the opposite. Before Becca’s house he said ‘See you tonight.’ ‘Oh, will you be at the Fürstenhof later as well?’ ‘May I join you beforehand at the theater?’ ‘Yes.’ With that yes, I suspected that I had consented to something more. His married sisters were at the theater. I would have been quite surprised if they had not been curious to finally see me, as I had expected. They joined us at the Fürstenhof and were nice, but I riled Dr. Oliven just to be difficult.”

After an indulgent evening at the Fürstenhof Hotel on Potsdamer Platz, Leonie was surprised:

“And the next morning I woke up and found a bunch of roses at my bedside. And I muttered that it wouldn’t do, it wouldn’t do, as I thought our views on life were too different. And right away he called and asked whether I would like to go for a walk with him at noon. And I agreed. […] Then I went shopping and did not think of anything until noon came around. There he stood, said he had a car waiting, and dragged me along. I chatted a bit about velvet dresses until he interrupted me and said, ‘You are a reasonable person. Do you believe that the two of us could live together?’ And I said, ‘I am afraid that you would grow unhappy because I am so resolute and we are so different.’ ‘Do you like me?’ ‘Yes.’ ‘Well, then, all is well […]. You are a reliable woman. […]’ Then he tried to give me a kiss on the cheek, which wound up in the air. At the zoo, we got out of the car and went for a walk; we sat on a bench and he took my hand and talked of so many things that a suitor does not usually say; and he would have loved to tell me all about his life right there; he does not like to carry burdens alone, he has such a need to talk. We did not mention the two years that had gone by at all. And then we went to the hotel. Papa was touched, Mama startled on the phone. As I had not confided in her when I left, she had no idea what to expect. We also visited Fritz’s mother, with whom he is very close.”

~~~~~

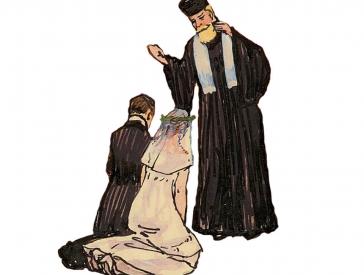

After Yom Kippur, Fritz came to Hanover for his first official visit:

Diary Entry Dated October 1911

“In Hanover, this was kept secret over Yom Kippur, which I found difficult, but after all, I have learned to be quiet. On Tuesday he came, and in the evening several relatives joined us. On Wednesday we went to Barsinghausen to have a chance for a quiet talk. It is strange how comfortable and free and easy we were immediately – intimate like a married couple from the first moment, no false shame, I don’t blush, am not ashamed of some thoughts; I would never have thought that one can speak so naturally with each other. Once I told him that most engaged couples did not converse so naturally with each other, because most grooms did not like their brides to look so informed. They want them to play the silly white goose. I would have adjusted, but he said that would not be necessary, and I find that makes things much simpler.

[…] I should never betray him, I should swear to it. I did not do so as one never knows what might happen. But I reassured him that it would only be caused by him if I did so, if he first overwhelmed me with tenderness and then let me starve. From the first day, when no one was watching, he taught me caresses beyond my imaginings, which bewildered me. I told him that these were agony at the beginning of an engagement, and he left off. I pull myself together and struggle to keep cool, as I tell myself that if I am totally open, then I have no recourse; I am too much in love already and give in, am much too soft.”

~~~~~

Over the following weeks, the two of them saw each other frequently, sometimes in Hanover and sometimes in Berlin. They got to know each other better and fell deeper and deeper in love, as Leonie described in her diary:

Diary Entry Dated 9 November 1911

“But Fritz is very good and every time he’s been here, I keep looking forward to our marriage more joyfully; I don’t have a bit of fear. I feel that in all he says and thinks he loves me dearly; there is a reflection of his joy in gaining me as his wife.

[…] He feels and thinks so decently and is not as conceited as I thought, boyishly happy when treated well; quite soft, but he knows what he needs for his happiness. The only reservation, which I stress to him all the time, is that he wants to give up his office and only write poetry at home. I am too much of a banker’s daughter, and being dependent on public opinion seems eerie to me. He needs a strong woman who remains steady, because if he should be unsuccessful or something bothers him, he gets depressed (he is so sensitive, the poor boy). And then he wants to run to me. And it is good that I am as I am. But still, it is an odd mixture that he demands, rich and strong. Will I remain so rich – as my character is quite solid, a little loud, domineering and managerial. But if he remains so tender and kind, then I am disarmed. In spite of his long bachelorhood, he still has much fresh, young tenderness left for me. I was somewhat saddened at first by his caresses, which seemed impassioned to me. A woman who has had to hide her desires for so long cannot feel comfortable immediately, this ‘pouncing on the man,’ as some do, is not my thing. First I was passive, felt almost ‘acquiescent,’ did not dare show my wishes, and was ashamed of them. But secretly I am grateful to him for his kind, carefully courting caresses, and the care that he shows me.“

~~~~~

But Leonie also experienced her first annoyances when she learned that they would have separate bedrooms in their apartment together in Berlin. Fritz said he couldn’t sleep with someone else in the room.

“And I could not say ‘no’ politely, which would have seemed too needy.”

And in the midst of their wedding preparations, the young couple had their first argument:

“I wanted to remove some guests from the invitation list, which Fritz did not appreciate. He was offended, so sad as though he wanted to cry. […] And now I have become timid, as I have a quick tongue and if my own husband is sensitive, it will be tough for me.”

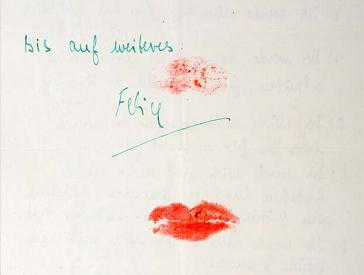

The diary had been Leonie’s trusted companion for a year and a half. On 11 January 1912, five days before the wedding, she wrote the final entry in a tone that drifted between wistfulness, anticipation, and trepidation:

X

X

“The Spouses to Be”

: Leonie Meyer and Fritz Oliven during their engagement, Hanover, October 1911; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2016/428/0, gift of the Oliven family

Diary Entry Dated 11 January 1912

“My engagement is coming to an end. It was a beautifully immaculate time. With each visit, Fritz becomes dearer to me, the good, faithful boy who can be so tender and kind – and cheeky. I still frightened by much and sometimes I am afraid of married life. And it does represent a bigger change for a girl than for a young man. I am leaving the city of my birth, which I am so fond of, my parents’ home, my circle of friends, for new surroundings, to lead a life totally different from the previous one. I am quite capable of adjusting quickly, but my new acquaintances do not yet match what my old friends were to me. And whether I will grow comfortable with my sisters-in-law right away, I don’t know. We are still a bit formal to each other. The same goes for my mother-in-law, and I am afraid that they will always be on Fritz’ side, as they are all so in love with him.”

~~~~~

The final lines read:

“But now I would like to close with the wish that the new life which I am about to begin will bring me as many joyful days, and as few dreary days, as my old one. And that my Fritz will remain just as he was during our engagement and that good fortune will preside over our marriage. May our love remain steady, renewed daily and eternally fresh, so that in time our marriage, having begun with a surfeit of love, shall not end with a dreary, habitual companionship. May illness and misfortune remain far from our doorstep.”

The diary entries were kindly translated by Vita Hollander of the Leo Baeck Institute, New York. They were edited by Jake Schneider, who also translated the remaining text of this feature.

Citation recommendation:

Jörg Waßmer (2021), “No,

I Want Dr. O.”. Leonie Meyer’s Diaries from the Years before her Marriage (1910–12).

URL: www.jmberlin.de/en/node/7741

Behind the Scenes: Anecdotes and Exciting Finds while Working with our Collections (22)