“... or was it the end of the world?”

David Fiks Reports on the Kristallnacht of 1938 in Berlin

Jörg Waßmer

“Now to your request my son. You ask of me an exact description of the November pogroms”

, wrote David Fiks on 13 May 1939 in a letter to his son Max. “There isn’t much to tell. Pogroms against Jews have always been, my son.”

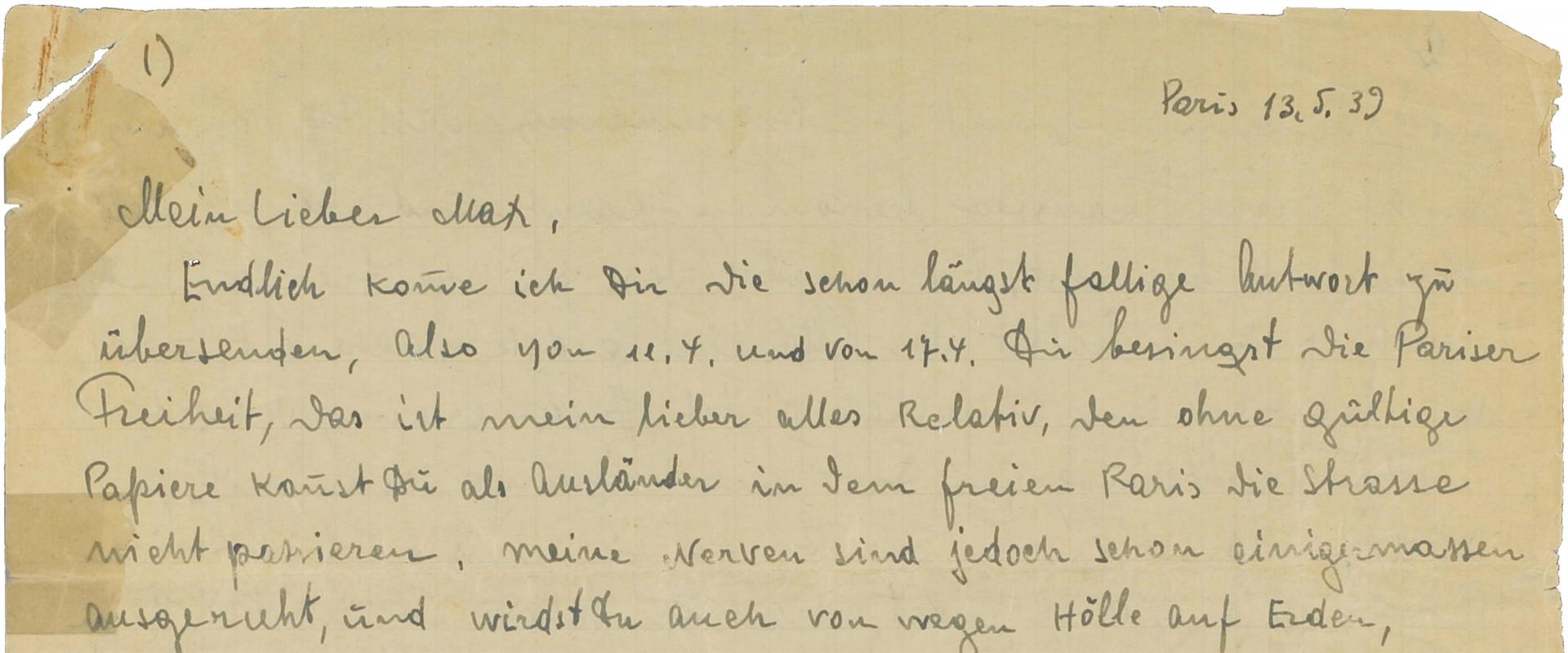

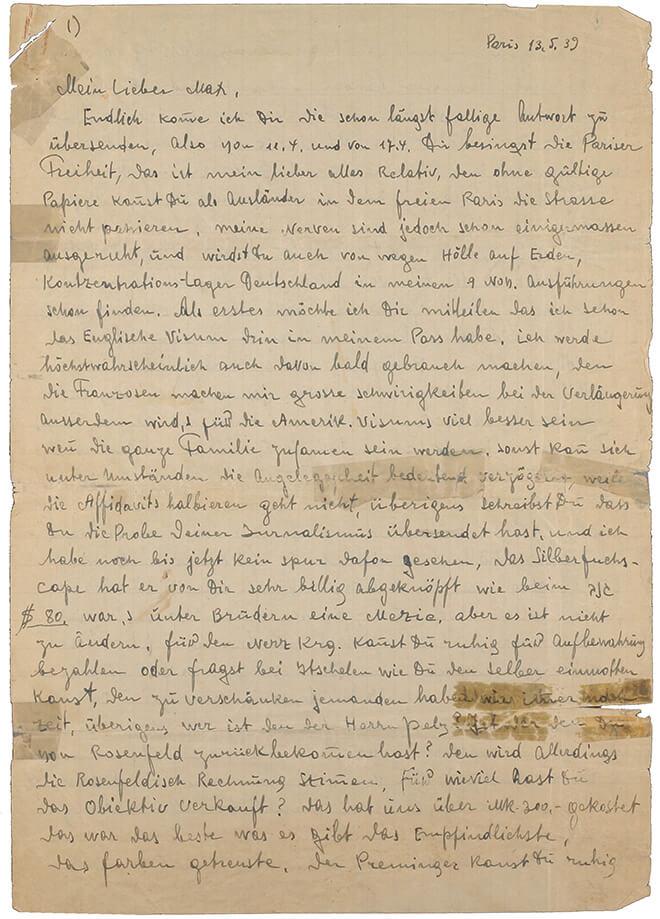

But the 45-year old eventually did agree to his son’s request and launched into the story. And soon the words were gushing out of him. The reader gets the sense that he is writing straight from the soul. By the time Fiks put down his pen, the letter amounted to some 22 densely packed pages describing in vivid detail the events of 9 November 1938, which became known by the euphemism Kristallnacht (The Night of Broken Glass), and the days that followed.

The Letter

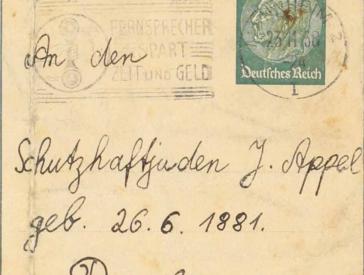

In the original German version, the letter is somewhat difficult to read. From its grammar and spelling, the reader quickly realizes that Fiks’s native language is Yiddish, rather than German. Born in 1893 in Rafałowska, a village that was then Russian territory, Fiks moved to Berlin as a young man and settled here. In 1920, he married Estera Kluger from Warsaw. They started a family and had three sons. The eldest, Max, was born in 1921 and was this letter’s recipient. In 1930, the Fiks family was granted Prussian and by extension German citizenship. Within four years, this citizenship was revoked by the Nazis. Under the Law on De-Nationalization, the Fiks were rendered stateless in December 1934.

X

X

First page of the letter from David Fiks to his son Max, Paris, 13 May 1939; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2004/7/0/1-11, gift of Max Fiks

David and Estera Fiks with their two sons, Max (1st from left) and Alfred (2nd from left); the third son died in childhood; Berlin, about 1937; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession R-2004/6/0, gift of Alfred I. Fiks. Further information about this photo can be found in our online collections (in German)

The letter is engrossing, an extraordinary historical document. Composed only half a year after the events it describes, it relates memories that were still fresh. Because David Fiks wrote it in exile in Paris, where he had taken refuge, and sent it to the United States, where his son Max lived, he wrote it without fear of the German postal censors. The direct and unencumbered language make clear that the report is very forthright.

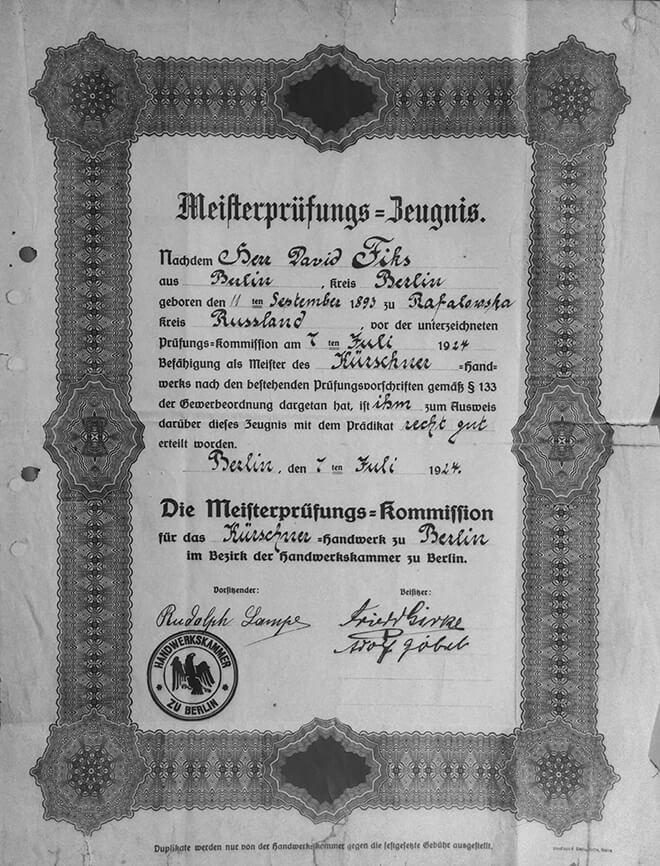

“D. Fiks, Master Furrier”

David Fiks was a furrier by trade. He completed his training in Warsaw from 1907 to 1911. He then worked as a furrier’s apprentice with an interruption for his military service in the First World War. “As 22-year old healthy, full of joy for life, and honest persons, we tried to make Berlin our second home. Our way was not strewn with roses. With effort and step by step we followed our path.”

On 7 July 1924, Fiks took his mastery examination in Berlin, receiving the grade “highly good,” and struck off on his own. He opened his first store at Sebastianstrasse 7 in Berlin’s central district of Mitte.

Two photographs survive of this store. One is the exterior view, which is unfortunately fragmentary, showing only part of the building’s facade. Painted on the wall in large letters is the word for “Fur Fashions” above the inscription, in smaller letters, that translates to “D. Fiks Master Furrier.”

X

X

David Fiks’s trade mastery certificate from the Berlin Chamber of Trades and Crafts, Berlin, 7 July 1924; Berlin State Office for Residents’ and Regulatory Affairs, BEG record registration no. 052653

Exterior View of David Fiks’s Fur Store at Sebastianstrasse 7, Berlin, between 1925 and 1930; Courtesy of Eliot Fiks

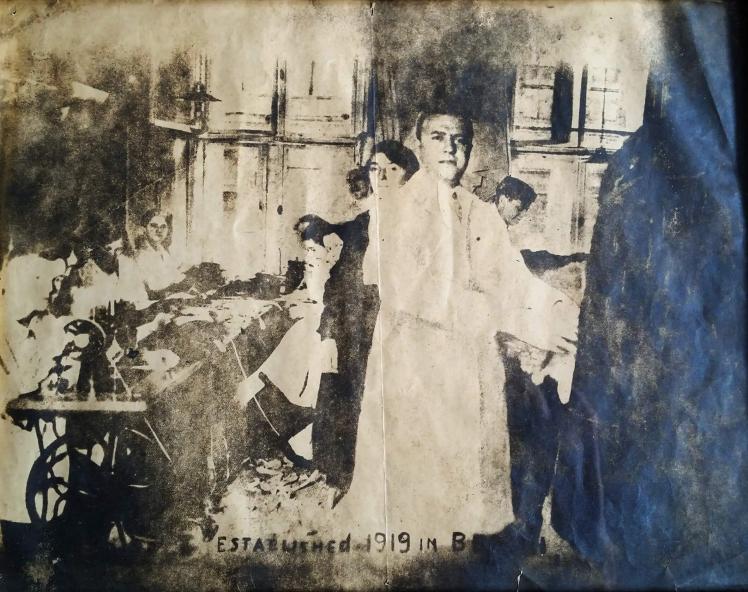

The photograph of the interior is so faded that the details are hazy. Fiks is standing beside a pelt in his workshop. He is wearing a floor-length work coat. Behind him, we can see his wife and several assistants sitting at sewing machines. A handwritten caption in English reads “Established 1919 in Berlin.”

David Fiks with his wife and assistants at his furrier’s workshop, Berlin, about 1925; Courtesy of Alfred I. Fiks and Erik Fiks

Extract from the Berlin Address Directory from 1938 with an Entry for “Fiks D Furrier 15 Uhlandstr 43 T.”

Later, Fiks moved to the stately Western part of town and opened a new store near Ku’damm, the city’s main shopping boulevard. The Berlin address directory indicates where he lived and operated his fur store at the time of the November Pogrom of 1938: Uhlandstrasse 43.

A Place Forgotten by History

As a staff member of the Jewish Museum Berlin’s Archive, I set off to retrace Fiks’s steps and visit the places he mentions in his letter. My first stop is in the Wilmersdorf district. The building currently at that address on Uhlandstrasse was built in the postwar period. The ground floor still holds a retail establishment, but it primarily sells wine, beer, liquor, and newspapers – not furs. This historic place has now been forgotten by history. There are no reminders of the horrors that took place here during the November Pogrom eighty years ago.

Family Memories

Five decades later, in 1987, David Fiks’s grandson Eliot took a walk down Uhlandstrasse. The young man had traveled from the United States to West Berlin in search of traces of his family history. He tried to visualize the events of the November Pogrom in the places where they happened. He captured his impressions in a series of black-and-white photos.

Coincidentally, he discovered a store selling furs in the neighboring building, Uhlandstrasse 45. It could have been his grandfather’s store.

Store selling fur-lined apparel at Uhlandstrasse 45, Berlin, 1987; Courtesy of Eliot Fiks

The door of an apartment building across the street had been left open. The thirty-one-year-old entered the prewar building and climbed its creaky staircase all the way to the attic. His grandfather, fearing for his life, had once hidden in an attic just like it in the neighborhood.

“At the last door, I rang for some seconds, and a 9-year old girl opened the door. I couldn’t form the words anymore, and speechless I thrust myself into the apartment. Her mother, a well-dressed Aryan lady appeared and asked me what I wanted. I answered sobbingly, ‘Save me, dear lady. They’re after me.’ ‘Who are you, then?’, was her question. ‘I am Fiks, no thief, no murderer, no traitor, no wretch. I am only a Jew and a family man. It’s a matter of life or death, hide me. Do with me what you will, I’m not leaving this apartment.’ ‘How dare you talk to me this way. My husband is a member of the Party Steering Committee and a ‘Gauleiter’. He’ll be back soon. He’ll probably shoot you right here, and I’ll get it too for daring to hide a Jew in my apartment.’ Then I had an idea: ‘Please lock me in your attic, and in a few hours, when it gets dark, let me out. You’ll save a father of a family and a human being!’ This, she finally agreed to do. And so, I spent about four hours under a laundry basket in the attic for drying clothes.”

“When, fearful of death, I ran out of the store and into No. 42, the super of that house saw me. He told it to Mother right away because she and Miss Joppek had looked for me on the street and thought they might have taken me away or even killed me [...]. Mother remained standing outside house No. 42, and when the beasts in human bodies realized that I had escaped, they spared no trouble to find me, alive or dead. They soon got word about my fleeing into No. 42, [...]. Though the super assured them that no Jew had run in there, they started searching the whole building, from the boiler room in the cellar up to the fourth floor, but, of course, without success.”

Attic of Uhlandstrasse 156, Berlin, 1987; Courtesy of Eliot Fiks

“Meanwhile, four hours had passed; the darkness of the night had fallen. Now, I thought, was the right time to leave my attic hiding place. The attic door had been unlocked shortly before. I started going down the stairs, and meet an old lady. I asked her if all was calm downstairs. ‘Depends what you mean by calm,’ she said. Running along the walls, I hurried home half frozen. When Mother heard me coming, she shouted as loud as she could, ‘Save yourself, quickly!’ and then broke down in crying fits. Marie stood in the hall with my coat and hat, and said, ‘Quickly, quickly, just now the officials were here looking for you once more’. I ran outside. Trudy stood in front of the building, and told me not to go to the left because the officials took that direction.”

David Fiks escaped Uhlandstrasse and took a taxi to Steglitz. I take the U-Bahn there and walk the final stretch to Bergstrasse. This was the home of Hedwig Schmidt, where Fiks tried to find an emergency hideaway. Her home is no longer standing. It was replaced by an apartment building after the war.

Fiks signed his letter to Max with the words “Your father who loves you”.

Then, as a P.S., he added an official “Note”

: “I assure that everything told here is true according to my memory [...].”

This casts the father’s personal letter to his son in a very different light. Fiks is delivering official testimony here of the German crimes.

Addendum at the end of the letter with an affidavit by David Fiks, Paris, 13 May 1939; Jewish Museum Berlin, gift of Max Fiks

Emigration and a New Beginning

On 29 April 1939, Fiks emigrated to France. His wife and his youngest son Alfred followed him there in August 1939. He had been forced to close the store at the end of 1938 on official orders from the District of Wilmersdorf. It was transferred to a “trustee,” who liquidated it. When the German Wehrmacht occupied France, the Fiks family stayed in the unoccupied zone. By way of Casablanca and Cuba, they eventually managed to immigrate to the United States in 1943. Their son Max, who was serving in the US Army, had secured them the necessary papers. In the New York borough of Brooklyn, David Fiks later opened a new fur shop (“Furrier-Designer, Storage – Repairing – Restyling”

).

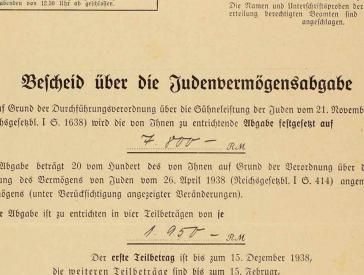

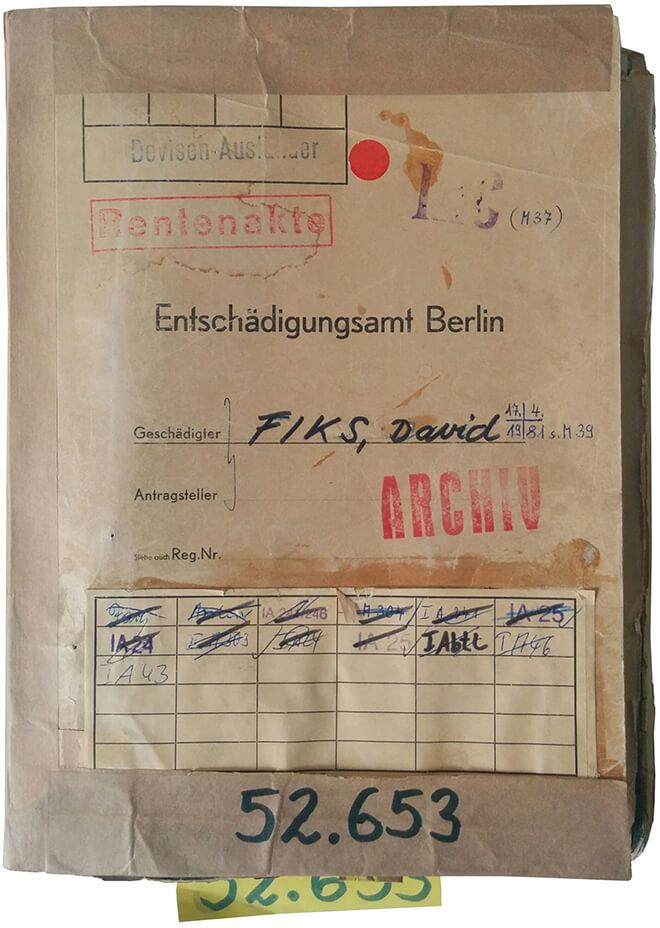

In 1951, he filed an application for reparations for the “harm to his property.”

Item 2 of the application form, which is stored at the Berlin Reparations Agency at Fehrbelliner Platz, bears the heading: “Brief description of the events: (if applicable, with notarized copies of associated documentation).”

The form gave four lines of space for the response. David Fiks kept it brief: “In the night of 9 to 10 Nov 1938, the storefront of my shop was smashed, the furniture inside destroyed, and my stock of fur goods looted. Of course there is no documentation of this episode, and no witnesses at present. (I will send notice of a name and address as soon as I identify one.)”

It took ten years before he was authorized to be paid 12,000 Deutschmarks for the full financial damages (incl. “surrender of Jewish assets,” “Reich Flight Tax,” etc.)

X

X

David Fiks’s Reparations File at the Berlin Reparation Office, 2018; Berlin State Office for Residents’ and Regulatory Affairs, BEG record registration no. 052653

Preservation

Max Fiks, the recipient of the letter, treasured it as a precious keepsake. During the decades after the war, the family gathered every year on the anniversary of the Kristallnacht and Max read out passages of his father’s letter. David Fiks died in 1981.

His youngest son Alfred finally translated the letter into English for the English-speaking descendants. The English version of the letter used here follows his translation.

In 2004, Max Fiks gave the original document to the Jewish Museum Berlin. This piece of testimony has been preserved in our Archive ever since. You can find the letter and a transcription of the full German text in our online collections.

Citation recommendation:

Jörg Waßmer (2018), “... or was it the end of the world?”. David Fiks Reports on the Kristallnacht of 1938 in Berlin.

URL: www.jmberlin.de/en/node/5853

Online Features: The Background and Ramifications of 9 November 1938 (5)

X

X

X

X