What Was Left of Summer

Arno Nadel’s Drawings and Notebooks as Eyewitness Testimony

The Jewish Museum Berlin’s collections preserve around 450 drawings as well as sketchbooks, music manuscripts, and notebooks by the artist Arno Nadel. Born in 1878 in Vilna (now Vilnius, Lithuania), he moved to Berlin around the turn of the century, where he made a name for himself as a composer, writer, musician, and painter. For many years, he conducted the choir at the synagogue on Kottbusser Ufer (now Fraenkelufer), composed and adapted synagogue music, collected and published Yiddish folksongs and love songs, wrote poetry and plays, and began painting in his forties – as a self-taught artist using pastel, chalk, and ink.

Arno Nadel’s Drawings

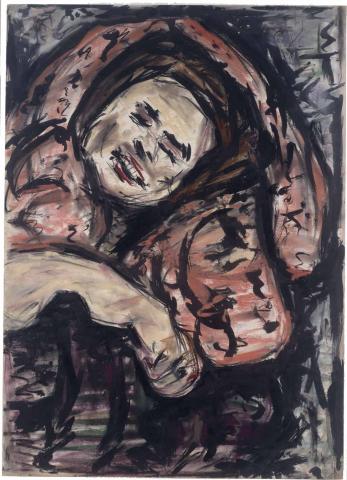

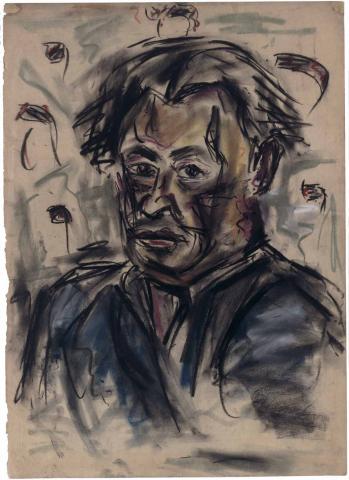

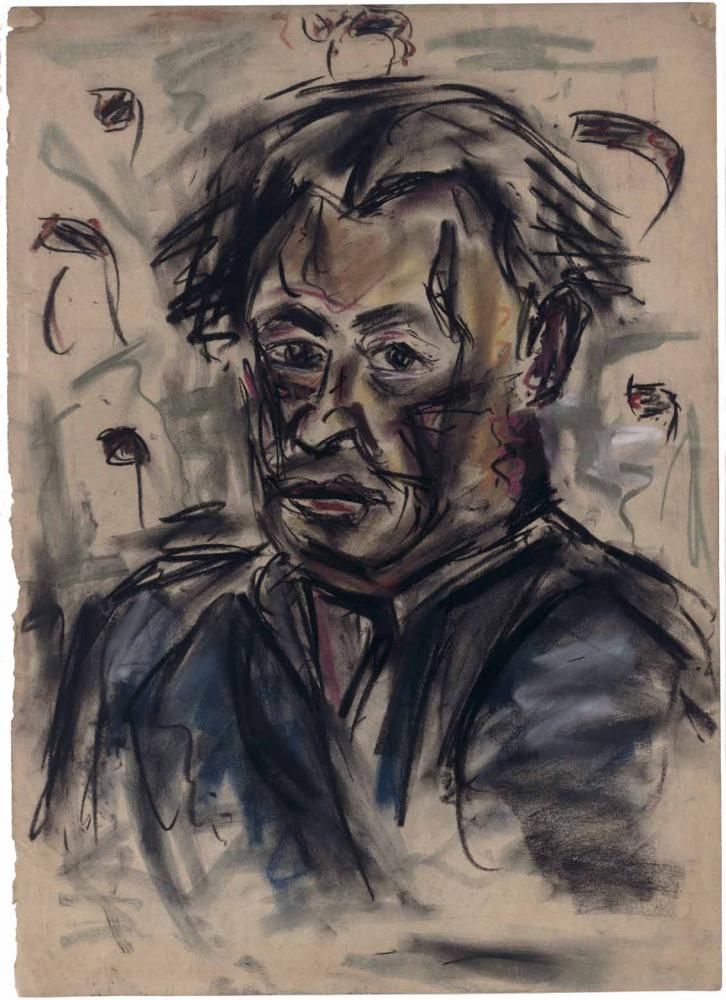

He was especially drawn to portraits. In addition to several self-portraits, he sketched his daughters Ellen and Detta, his wife Anna Guhrauer, and numerous as-yet-unidentified muses and companions. His works are colorful, expressive, and at times even exuberant. A distinctive feature is his tendency to combine text with imagery – he often incorporated names, words, or quotations directly into his drawings. In the 1920s, he created a series inspired by theatrical productions, including performances by Moscow’s Habima Theatre in Berlin and Max Reinhardt’s Artisten (Acrobats). This followed in the 1930s by his series Biblische Gestalten (Biblical Figures), including about 40 portrayals of biblical characters.

Nadel’s drawings are not only striking works of art, but also poignant records of their time: they capture his apartment, which he was forced to vacate in 1941; summer landscapes he could no longer visit by 1942; and close friends who were later deported.

X

X

Arno Nadel, Color pastel drawing of a laughing woman lying on a pink cushion, undated, pastel and ink on cardboard, 53.9 × 75.1 cm; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 1999/96/58, photo: Jens Ziehe

A Diary of Nazi Book Theft

In 1938, Arno Nadel was imprisoned for several weeks at Sachsenhausen concentration camp. A family friend later described him as a broken man after his release. In 1941, he and his wife were forcibly relocated to a one-room apartment. In a letter to his daughter Detta, who had emigrated to New York with her husband, he wrote:

“My golden children – relocation!!! We have one room with very nice people – but you’ll have to picture all of it, every bit, with your own imagination. It’s certainly no home, and my atmosphere is out the window. I’m not painting, not making any music – thank God that at least I can finish dictating my second major work, I mean, my ‘sooth-saying Dionysis.’”

Beginning in February 1942, he was forced to work in the library of the Reich Security Main Office, where he was made to pack, stack, sort, and catalog books looted by the Gestapo. During this time, he began writing a diary that he considered his third major work. In it, he reflected philosophically on the books he handled at the “G.U.” – his abbreviation for the library at Eisenacher Strasse 12–13 in Berlin’s Schöneberg district. The diary not only captures his inner world, but also documents the systematic plunder of books by the Nazi regime. He also used it to record his daily life: the growing number of suicides and “evacuations” among his friends, and his own deepening despair and sense of hopelessness.

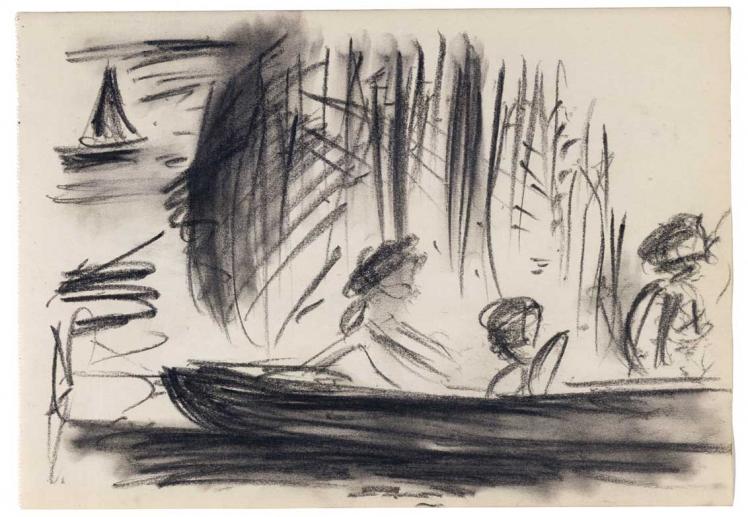

Arno Nadel, Summer scene, August 1939, charcoal on paper, 22.5 × 32.3 cm; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 1999/96/17, photo: Jens Ziehe

The Last Summer

Among the drawings at the JMB are landscape sketches that Nadel made outside Potsdam in the summer of 1939. Three years later, he wrote in his diary:

“Where are my summer drawings – the swimming, the boat rides and steamer trips, the full riverbanks, the naked and half-naked people in and near the water […]. If it has to remain this way, then let that be the last summer – at last I know what freedom means.”

The summer of 1942 did in fact prove to be Arno Nadel’s last. When he returned from forced labor on 10 March 1943, he found the apartment officially sealed: Anna Nadel had been “taken away.” Friends offered him a hiding place, but he decided to follow his wife. On 12 March 1943, Arno and Anna Nadel were deported to Auschwitz, where they were murdered.

X

X

Arno Nadel, Self-portrait, ca. 1920–1938, pastel on paper, 62.5 × 44.8 cm; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 1999/96/106, photo: Jens Ziehe

How did his drawings survive?

Until the bitter end, Arno Nadel maintained contact with his shrinking circle of local friends, including several non-Jewish confidants. Aware that he could no longer save his own life, he entrusted those friends – who were not at risk of persecution – with his most important manuscripts, sheet music, drawings, and his diary. That is how some of his work was preserved and is now housed in public institutions in Jerusalem, New York, and Berlin.

The drawings now in the Jewish Museum Berlin had been given to his friend Walter Heinrich for safekeeping. The two shared a passion for philosophy and Heinreich likewise rejected the Nazi dictatorship. It is unclear why these works remained with Heinrich after the war rather than being passed on to Nadel’s daughters, who lived in the United States and France. After Heinrich’s death, the works entered the art market through various intermediaries and eventually came to the JMB.

We are currently in contact with Arno Nadel’s heirs and are working together to find a just and fair solution regarding his drawings.

Elisabeth Weber, Provenance Researcher at the JMB

Behind the Scenes: Provenance Research at the JMB (4)