In a Foreign Country

Publications from Displaced Persons Camps – The Berlin State Library in the Jewish Museum Berlin

In the immediate post-war years, hundreds of books were published in the camps set up for Jewish displaced persons, mainly in Yiddish and Hebrew. The Berlin State Library resolved some years ago to collect these publications systematically.

In the display cases of this 2015 exhibition, we presented for the first time a portion of this literature, which was published in Germany but not initially intended for German readership. Its readers were involuntarily stranded here and felt itself to be, as the title of one book in the exhibition put it, In a Foreign Country.

Past exhibition

Where

Libeskind Building, lower level

Lindenstraße 9–14, 10969 Berlin

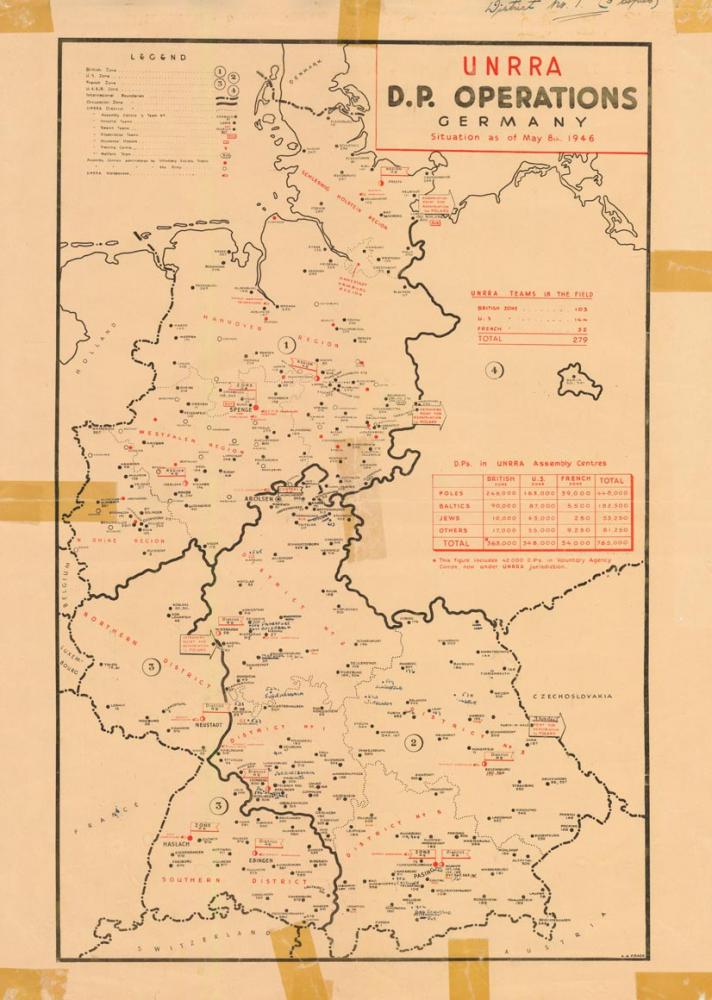

The publications document a largely neglected chapter in the history of the Jewish presence in Germany after the Shoah. As many as a quarter of a million Eastern European Jews reluctantly made the Allied Occupation Zones of Germany their temporary place of residence. The works shown here reflect the everyday existence of a provisional community whose ultimate goal was to migrate to Palestine/Israel, the United States, or other countries.

The exhibits included magazines, newspapers, schoolbooks, Zionist pamphlets, Passover haggadot, and even a tractate of the Talmud from St. Ottilien in southern Germany. There were also volumes of prose and poetry from the Berlin State Library’s collection: impressive testaments to survivors’ need to begin writing about their traumatic pasts as soon as the war was over.

A Small Selection of the Objects

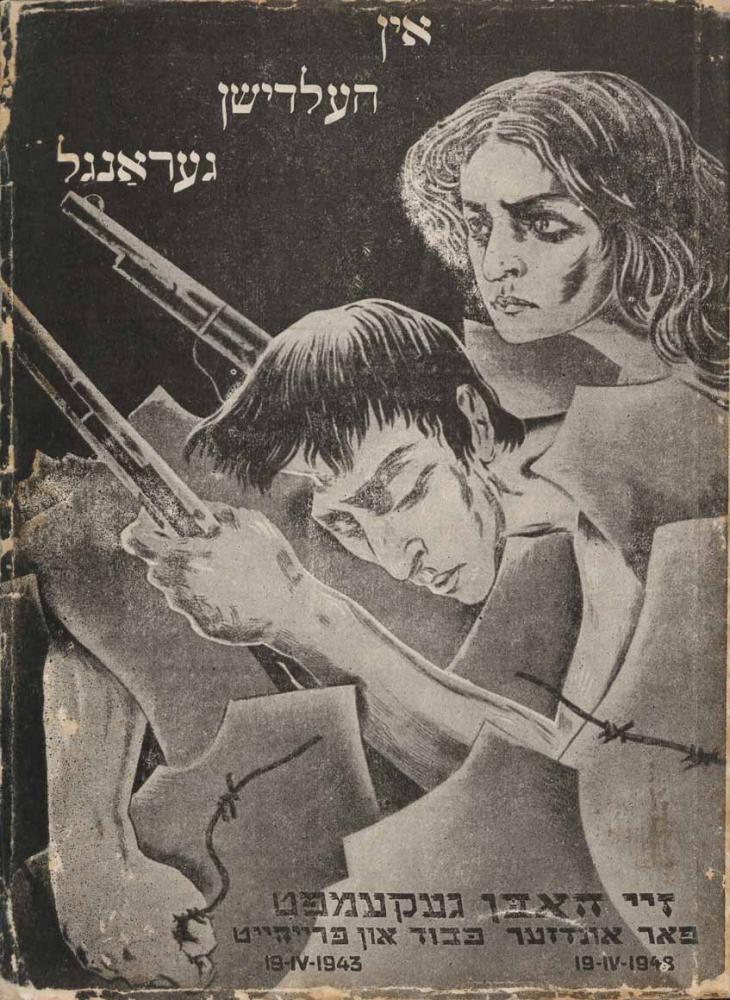

In heldischn Gerangl, anthology on the uprising at the Warsaw Ghetto, New York 1949; Illustrations: Berlin State Library – Prussian Cultural Heritage

Zurik zum Lebn by Malke Kelerich, Munich 1948; Illustrations: Berlin State Library – Prussian Cultural Heritage

The featured publications are neither elaborately nor extravagantly illustrated, with few exceptions. Nonetheless, they are precious because they bear traces of their former owners and their history.

Titles such as Our Courage, Our Path, Our Voice, Our Word, and On the Move indicated the start of a new life and were on equal footing with magazines like Fun leztn Churbn (Yiddish: On the Latest Devastation), which discussed the history of the Jews during the Nazi regime. Autobiographical texts also describe life in Germany including hateful and traumatic encounters with the German civilian population.

The exhibition was divided into four sections:

I. The Surviving Remnant

Drawing on a Biblical expression, the Jewish DPs called themselves “She'erit Hapletah,” the surviving remnant. Physical nourishment and medical care were not all they needed. After years of deprivation, the DP camps were their first postwar experience with civilization and culture, their first opportunity to satisfy their religious and intellectual needs as well.

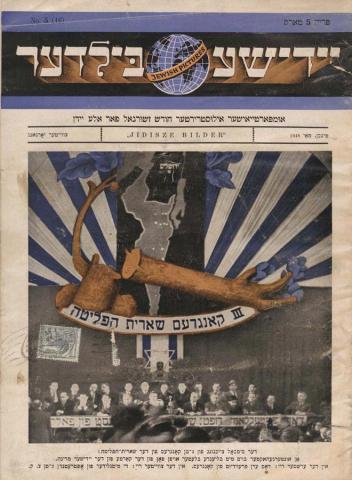

Tkhies Hameysim (Yiddish/Hebrew: The Resurrection of the Dead) was a handwritten newspaper published in the liberated Buchenwald concentration camp a few days before the end of the war. Beginning in the fall of 1945, when the supplies in the DP camps gradually stabilized, the survivors began to establish a regular press. Newspapers and journals provided information about political developments, reported on life in the DP camps, and contributed to general education.

Over time, several small presses were founded, although their numbers remained few. From 1947, writers presented new works to the reading public. By 1950, approximately thirty volumes of poetry and prose had been published in Yiddish.

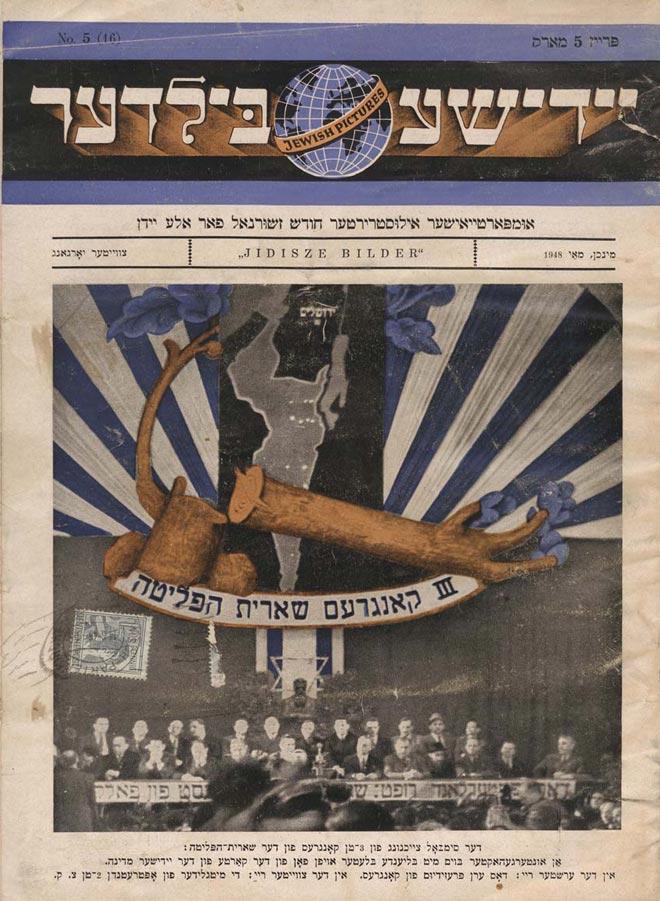

The title page of No. 16 of the illustrated monthly newspaper Jidische Bilder. Umparteijischer jidischer Chojdesch-Zhurnal far ale Jidn shows a colorized view of the third Congress of Liberated Jews in the American occupation zone in Bad Reichenhall. Behind the presidium, the Sche’erit Hapleta symbol can be seen, a felled tree with a new shoot in front of the map of Palestine; Illustration: Berlin State Library – Prussian Cultural Heritage

X

X

The title page of No. 16 of the illustrated monthly newspaper Jidische Bilder. Umparteijischer jidischer Chojdesch-Zhurnal far ale Jidn shows a colorized view of the third Congress of Liberated Jews in the American occupation zone in Bad Reichenhall. Behind the presidium, the Sche’erit Hapleta symbol can be seen, a felled tree with a new shoot in front of the map of Palestine; Illustration: Berlin State Library – Prussian Cultural Heritage

II. On the Latest Devastation

Immediately after the liberation of the concentration camps, survivors began to document the Khurbn or devestation. Historical commissions interviewed witnesses and collected documents, photographs, and artifacts. They presented the results in exhibitions and publications.

The commissions repeatedly called on the Jewish public to participate actively in the documentation process. Within the She'erit Hapletah, as historian Israel Kaplan put it, history lay on the tip of everyone’s tongue.

A number of survivors had the personal impulse to document their stories and the histories of their destroyed communities in a journalistic or literary form. The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising of 1943, regarded as the symbol of heroic resistance, played a central role.

X

X

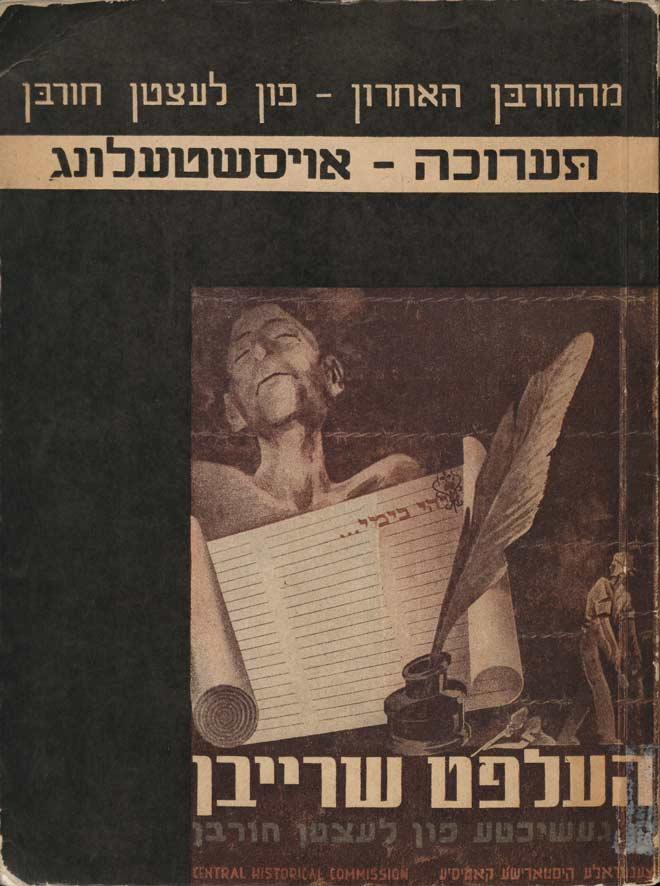

Exhibition catalog Fun leztn Churbn – Taarucha published by Israel Kaplan, Munich: Central Historical Commission, 1948; Illustration: Berlin State Library – Prussian Cultural Heritage

III. Education and Emigration

The first schools in the DP camps were opened as early as the summer of 1945. However, there was an initial lack of schoolbooks. Instructional material sent from Palestine and the United States was reproduced in Germany and helped to tide the schools over.

In elementary and vocational schools, instruction was oriented towards emigration to Palestine (or later Israel). Jewish history and Hebrew language instruction were central components of the curriculum. Zionist groups also familiarized their members with their vision of life in a future Jewish state.

Zionism was the predominant ideology of the She'erit Hapletah. For homeless DPs, it held the prospect of a new national affiliation. More than half of the DPs ultimately emigrated to Palestine/Israel and over 70,000 went to the United States.

X

X

Im fremden Land, poems by Mates Olitski, Eschwege 1947; Illustration: Berlin State Library – Prussian Cultural Heritage

IV. Religion and Tradition

Jewish DPs had markedly different backgrounds – both geographically and economically – as well as diverse native languages and wartime experiences. In regards to religious observance, they spanned the entire spectrum from secular to Orthodox.

Aid organizations worked to establish the prerequisites for religious life in the DP camps. They set up kosher kitchens and ritual baths and distributed phylacteries and prayer shawls. Talmud academies and religious elementary schools for boys and girls were also founded. Reprints of religious works that had been sent to Germany from overseas were used as instructional materials.

Holidays were observed and acquired a new significance after the Shoah, especially Passover and Purim, in which enslavement, danger, and liberation are central themes.

X

X

The songbook Schiron la-Chaluz we-la-Noar (1948) from the Tora we-Awoda movement (Torah and work) emphasizes the importance of religion compared to other Zionist songbooks; Illustration: Berlin State Library – Prussian Cultural Heritage

Exhibition Information at a Glance

- When 3 Sep to 15 Dec 2015

- Where Libeskind Building, lower level

Lindenstraße 9-14, 10969 Berlin

See Location on Map