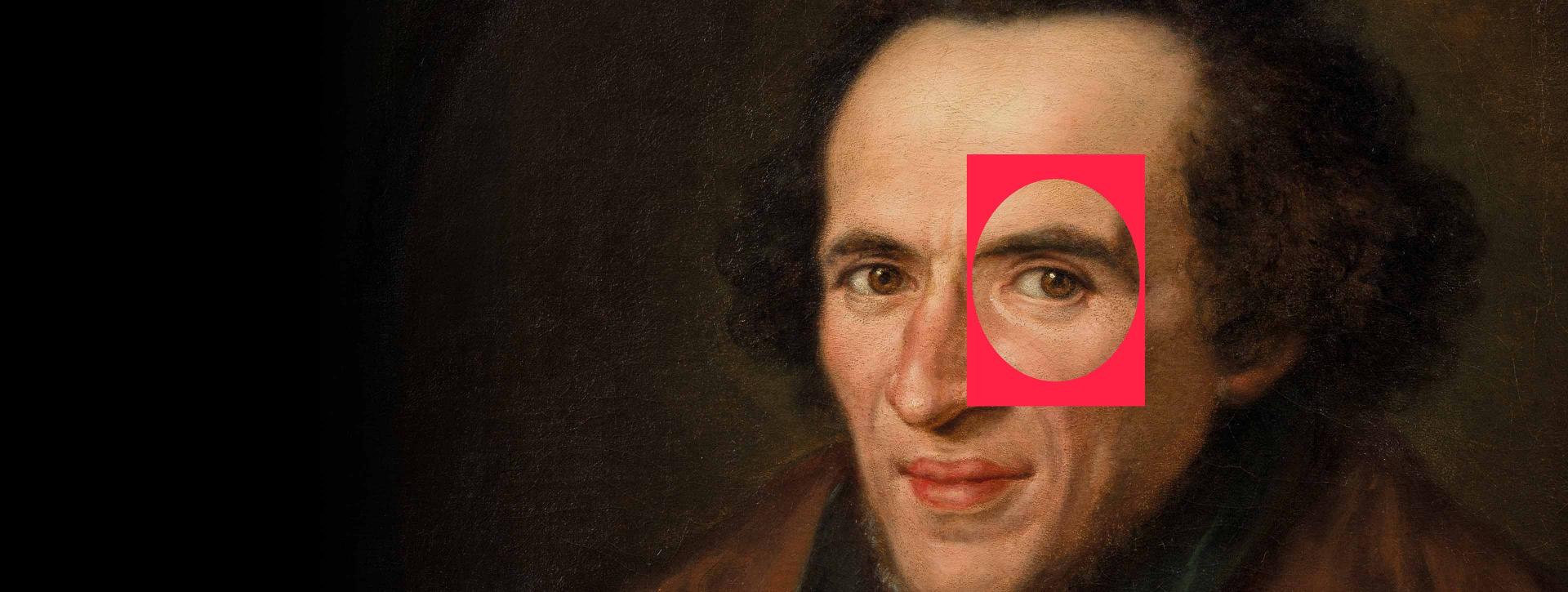

Moses Mendelssohn

A Deep Dive into Themes of the Exhibition “We dreamed of nothing but Enlightenment”

The eighteenth century marks the beginning of the end for an age that is set in its ways. Early Modern ideas about humanity, aesthetic conventions, and structures of governance are shifting, reaching towards modernity. The old way cannot go on. Natural disasters and religious wars are shaking the foundations of faith. Many of the questions being asked now will remain relevant into the 21st century:

Who will be granted residency? How do you talk to people you disagree with? How can fake news be stopped? Do equal rights require abandoning one’s own traditions? Does social integration weaken cultural identity?

In the eighteenth century, rational arguments are gaining sway. All eyes now fall on the Enlightenment – the clarity of sunrise! But the guardians of religious traditions do not tolerate being questioned. Monarchs reign supreme. Civil rights are restricted and human rights not even invented yet. But change is in the air.

Moses Mendelssohn travels to Berlin as a teenager. Together with his friends, he will become the engine of the Berlin Enlightenment and a bridge-builder for the Jews. Defying die-hards and distorters of facts, he champions the power of reason.

Join us on an exploration of Mendelssohn’s life and the debates of his era.

Panoramic view of the town of Dessau, engraving, Zerbst 1710; Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Roman März. Dessau is the capital of the principality of Anhalt. After the Thirty Year’s War, the ruling prince decides to reform his realm. Jews are part of his economic policy.

From Dessau to Berlin

Any outsider who migrates to the Prussian capital begins as a nobody. Dessau and Berlin have connections – but also frictions. Prussia needs useful immigrants. When it comes to Jews, the “right to stay” is reserved for the wealthy, not the poor.

Moses, born in 1729, is the youngest of three children. His father, Mendel, serves as the teacher and sexton at Dessau’s synagogue. His ancestors on his mother’s side have been great scholars for twenty generations. Moses studies night and day at Rabbi David Fränkel’s Talmudic school, where he stimulates his sharp mind. Encountering 500-year-old writings by Maimonides (around 1135–1204), he delights in their logic, their free-thinking spirit.

When Fränkel is appointed Chief Rabbi of Berlin, the 14-year-old Moses follows him there. Berlin becomes a portal to a new world. The starving student masters the classic canon and Western European languages.

Moses Mendelssohn’s day job as a bookkeeper at a silk factory protects him from eviction. Meanwhile, he befriends some of the local scholars. He publishes early writings, first anonymously and later under the name Moses Mendelssohn. His career as an intellectual turns heads. People marvel at this unusual Jew, this “Jew from Berlin.” The philosopher becomes a luminary of progressive thought.

Moses and his wife Fromet, the daughter of a Hamburg businessman, marry for love. They act as a couple – a profound partnership.

“Before I met you, my love, solitude was my Garden of Eden. But it is intolerable to me now.” (Berlin, 24 October 1761)

In the letters they exchange during their engagement, they are already discussing major spiritual and worldly questions (read more about these courtship letters on our website). Their marriage initiates the important Mendelssohn dynasty.

Torah Curtain made from Fromet's wedding dress; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession KGT 97/1/0, purchased with funds provided by Stiftung Deutsche Klassenlotterie Berlin, photo: Roman März. More about the curtain on our website ...

X

X

Torah Curtain made from Fromet's wedding dress; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession KGT 97/1/0, purchased with funds provided by Stiftung Deutsche Klassenlotterie Berlin, photo: Roman März. More about the curtain on our website ...

Biographical Documents and Objects

Moses Mendelssohn’s eyeglasses and case, 1751–1800, horn, glass, coated and embossed leather; courtesy of the Leo Baeck Institute, New York

Letter by Christoph Friedrich Nicolai to Johann Peter Uz , Mar. 26, 1759 about Moses Mendelssohn, his “close friend” and “one of the great geniuses.”

Read along: Nicolai about Mendelssohn

The publisher and Enlightenment thinker Friedrich Nicolai remains at Moses Mendelssohn’s side until the end of his life, longer than any of their intellectual allies. His letter to the poet Johann Peter Uz, written during the first years of that friendship, includes the earliest biography of Mendelssohn. Nicolai describes how it all began: with shared learning adventures, sincere admiration, and deep affection.

“Berlin, March 26, 1759

Most Honorable Sir and Friend,I hope you will allow me to refer to you by the latter title, which I have not yet had the chance to earn, as I will require your friendship to excuse myself for the long delay in my reply to your kind letter—to some degree, my excuse is the bustle of business dealings amongst which I live; I scarcely find time for myself. [...]

I threw myself onto this track, as it were, without considering how much toil would await me. Herr Moses helped me afterwards, and being my friend is his sole reason for remaining occupied with the arts and letters, which are otherwise not his domain.

Mr. Moses keeps to the synagogue, and why should he not?—He is one of the greatest geniuses Germany has ever had; the story of his acquisition of knowledge persuades me very greatly of the uselessness of our university studies.—Herr Moses owes nothing to any oral instruction. He is a native of Dessau, and until age fourteen could read no language but Hebrew, not even proper German. By then the Jews considered him a great Talmudist, and he was already meant to marry a rabbi’s daughter. Around that time, he succumbed to a kind of nervous condition or English ailment, which caused him to hunch although he had previously stood erect. He walked to Berlin on foot, where as an impoverished boy, a Jew offered him a garret where he could study Talmud. There, he studied day and night and knew nothing of the outside world. He also studied philosophy and mathematics from Hebrew texts. [...] Within a short time, he taught himself Latin, French, and English. From a Jew, Herr Gumpertz (a good mathematician), he became familiar with Wolff, the philosopher, and soon read all of Wolff’s Latin writings very attentively, writings very few can boast of having read.

The same Dr. Gumpertz recommended him to a Jewish merchant as a tutor for the man’s children; and after educating the son and daughter most judiciously, he has been entrusted with running the silk factory belonging to said merchant, Isaac Bernhard, for several years now. He works at the office until around 4 o’clock in the afternoon and spends his remaining hours, until midnight, studying. Herr Lessing first led him to concern himself with the arts and letters, and it was he who also coaxed his philosophical books out of him, so to speak, which he then published. [...] For a few years now, we have read Greek authors with the guidance of an experienced Hellenist; we have now moved on to Homer, a poet exceedingly to Herr Moses’s taste.

He has the best heart. How happy I would be if I could always be around him. I have never had a dearer friend. [...]”

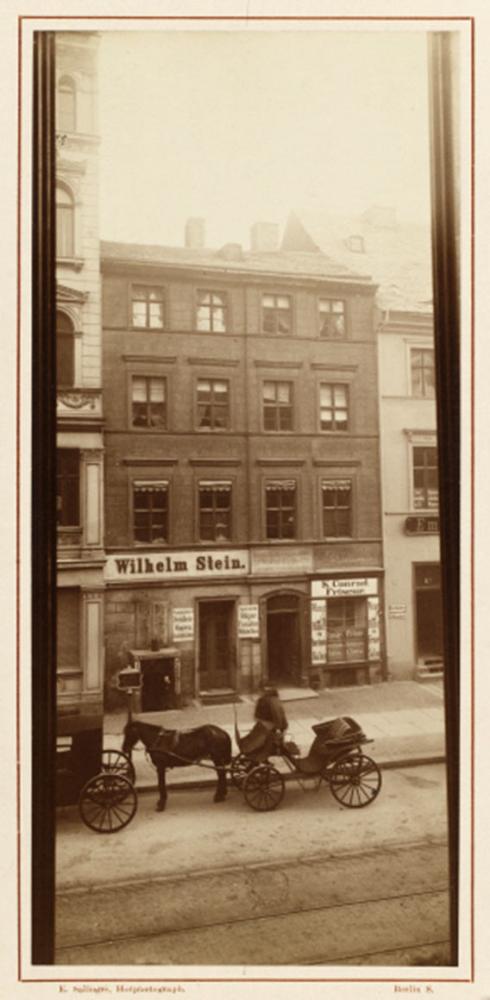

Open house at Spandauer Str. 68, Berlin: The Mendelssohns live here with their children; six out of the ten live to adulthood. Their home becomes a place for discussion for people from a wide range of backgrounds and religious affiliations, Berlin 1886; from the collection of Berlin City Museum Foundation; reproduction: Michael Setzpfandt

A New Culture of Public Debate

Citizens are making themselves heard. Outside royal and princely courts, new public spaces are emerging in cafés, scholarly societies, and publications. The exchange of ideas crosses national and class lines. Humanities scholars, scientists, artists, writers, journalists, and civil servants meet in public, semi-public, and very private spaces. They converse, debate, and learn the art of civil discourse at the Baumann’s Cavern wine hall, over billiards at the Learned Coffeehouse, at meetings of the Monday and Wednesday Societies, and in gardens and pavilions on the city’s outskirts. Ideally, what matters is the argument, not who makes it.

Spaces for New Dialogue: main room of a public coffeehouse, pen and ink drawing, 1770; Dresden, Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Inventory no. C 6638 © bpk | Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden | Herbert Boswank

Mendelssohn becomes an expert at dialogue. He writes books structured as conversations, as exchanges of letters. He considers the opposing viewpoint.

As a magazine contributor, an editor, and the host of debaters from varied backgrounds, he defends the diversity of opinions, helps the rationalists reach consensus – and takes part in utopian moments of mutual understanding.

“I visit Mr. Nicolai quite often in his garden. (I love him genuinely, dearest friend! And I believe our own friendship must further benefit from that, for in him I love a true friend of yours.) We read poetry; Mr. Nicolai reads me his own drafts aloud; I sit on my critical judge’s bench, admiring, laughing, affirming, criticizing, until night falls. Then we think of you once again, and part ways, satisfied with our day’s duty...” (Moses Mendelssohn to Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, Aug. 2, 1756)

Mendelssohn’s Closest Friends and Debate Partners

Gotthold Ephraim Lessing (1729–1781), poet and Enlightenment thinker. Alongside Mendelssohn and Nicolai, the principle member of the “Three Stars” group and the chief confidant, muse, and ally of Mendelssohn.

Painting by Anna Rosina de Gasc (1713–1783), oil on canvas, around 1767/68; CC-BY-NC-SA Gleimhaus

Elisa von der Recke (1754–1833), poet, half-sister of Duchess Dorothea of Courland, admirer of Mendelssohn.

Painting by Joseph Friedrich August D’Arbes (1747–1810), Berlin, 1784, oil on canvas; Stiftung Stadtmuseum Berlin, Inv. No GS 98/30 GM, reproduction: Oliver Ziebe, Berlin

Christoph Friedrich Nicolai (1733–1811), bookseller and publisher, longstanding friend of Mendelssohn, his partner in numerous journalistic and publishing projects.

Johann Michael Siegfried Lowe, C. F. Nicolai, Berlin, 1806, stipple engraving, 45,5 cm x 33,5 cm; Stiftung Stadtmuseum Berlin, Inv. No XI 19805, reproduction: Oliver Ziebe, Berlin

Dorothea of Courland (1761–1821), duchess and diplomat, admirer of Mendelssohn.

Painting by Joseph Matthias Grassi (1757–1838), undated, oil on canvas; Lindenau-Museum Altenburg, photo: Bertram Kober, Punctum

Thomas Abbt (1738–1766), philosopher, close friend and debate partner of Mendelssohn’s.

Portrait by Johann David Schleuen (1711–1774), Bückeburg, 1766, engraving; Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Roman März

Enlightenment versus the Shadows

Thanks to new newspapers and magazines, a bewildering flood of information reaches more and more people. Often the new knowledge conflicts with old beliefs. Science says: reason + experience = truth. The Enlightenment thinkers battle against superstition, conspiracy theories, and esotericism.

“We dreamt of nothing but Enlightenment and believed that the light of Reason would so illuminate the land that zealousness would never again show its face. But as we can see, from beyond the horizon night is ascending once again with all its ghosts. Most frightening of all is that evil is so active, so potent. Zealousness takes action, while Reason contents itself with speech.” (Moses Mendelssohn to Johann Georg Zimmermann, 1784)

Schwärmerei: An Enlightenment Battle Cry

For German Enlightenment thinkers, the word Schwärmerei – which very roughly translates to sentimentalism – became a battle cry with which they castigated their opponents.

Originally, during the Protestant Reformation of the 16th century, the moniker of Schwärmer designated the Reformation’s own radical fringes – its left wing, specifically the Anabaptist movement. During the Enlightenment era, Schwärmerei did not refer merely to religious fanaticism. By then it had become a broader term for irrationality, hostility to reason or truth, superstition, esotericism, and anything morbidly far-fetched or foolish. Today we might apply the same word to conspiracy theories or “alternative facts.”

In parallel, there were attempts in the 18th century to give the synonym “enthusiasm,” which also held negative connotations at the time, a more positive spin and to delimit it from Schwärmerei. Mendelssohn pays tribute to enthusiasm in Thoughts on the Expression of Passions (1762–63), although he believes this too must be kept in check.

Mendelssohn criticizes the approach of fighting Schwärmerei with mockery as unsuitable:

“In the end, mockery does not teach any lessons. It it not genuine Enlightenment if people seek to conceal their foolishness for fear of being mocked. Then, at the very most, they put on a mask of common sense, and even mock along where this tone is fashionable. [...] Rather than mockery – the only means for promoting true Enlightenment is, indeed, Enlightenment. People cannot be laughed out of their false ideas and preconceived notions about God and Divine Providence through satire, and neither can they be frightened out of it through external power and prestige. [...] Insofar as a century distinguishes itself by a tendency towards sentimentalism [Schwärmerei] or superstition, it is an exigency of time.” (Berlinische Monatsschrift, 1785)

Science and Progress

The World of Facts: Investigating nature is compatible with Jewish tradition, but the new scientific insights pose a challenge. Can the two be reconciled?

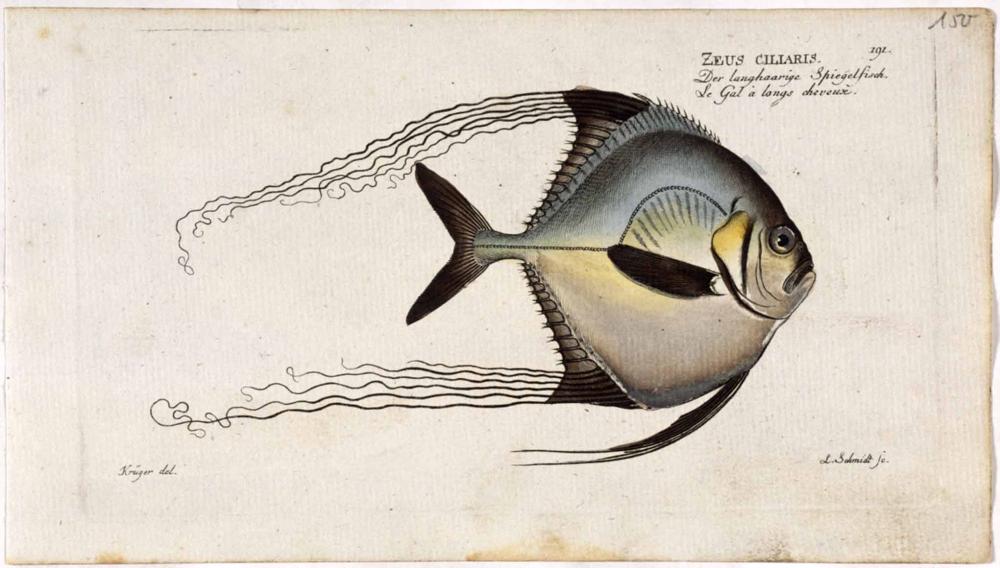

Marcus Elieser Bloch (1723–1799) was co-founder of the Berlin Society of Naturalist Friends, author of the twelve-volume General Natural History of Fish, Mendelssohn’s friend and primary physician.

Ludewig Schmidt after Krüger junior, Zeus Ciliaris: The “long-haired mirror fish” [African pompano]. From Marcus Elieser Bloch’s Naturgeschichte der ausländischen Fische (Natural History of Foreign Fish), 1787, copperplate print, hand colored on rag paper, 11.6 x 20.5 cm; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2001/3/3, photo: Jens Ziehe

Further information on this object can be found in our online collections (in German)

The Risks of Progress: On Dec. 26, 1783, Mendelssohn writes about the very first flight of a hot-air balloon in the Wednesday Society’s circular. He predicts Montgolfier’s discovery would likely lead to “great upheavals.” It deserves support, he writes, even if positive effects could not be guaranteed.

Johann Rudolf Holzhalb (1723–1806), “Demonstration of the famous Aerostatic Air-Sphere, which ascended into the air for 40 minutes at 1 o’clock in the afternoon on Decemb[er] 1, 1783 above one of the ponds at the Royal Tuileries Garden in Paris”, after 1783, etching, partially colorized; Zentralbibliothek Zürich, Inv.-Nr. Varia Ballone und Luftschiffe I, 4

How the Universe Ticks: As a popular philosopher and metaphysician, Mendelssohn concerns himself with basic questions of existence, with the Enlightenment and its enemies, and with the boundaries between faith and reason.

“A person can imagine all the springs, gears, and workings of a clock without fundamentally considering why these vessels are interconnected.” (Moses Mendelssohn, 1755)

Joseph Rose & Sons (1765–1784), English pocket watch belonging to Moses Mendelssohn, verge watch, repoussé, with double case, undated, metal, glass; Mendelssohn-Gesellschaft e.V. Berlin

As a learner, Mendelssohn takes in the world. He is a mathematician, metaphysician, psychologist, and literary scholar. He opens up the rationalist system to embrace a complex conception of humanity. There are two tools for achieving human fulfillment. The first involves day-to-day practical skills: culture. And the second is the gift of reason: the Enlightenment. Thinking for oneself, however brave, is not the goal.

Education helps break down the blinders that religions and communities use to segregate themselves – or so Enlightenment thinkers hope.

“The fountainhead of evil cannot but be stoppered by Enlightenment. If the area is illuminated, the ghosts disappear. May that which relishes creeping in the dark be drawn into the light; may everything that can be learned about the efforts, secret connections, institutions, and activities of sentimentalism [Schwärmerei] be unveiled: with contempt against the deluder, wherever he can be exposed; or, mercifully and without any satirical hostages, against the deluded one who deserves sympathy but not scorn. [...] The fate of humanity overall is this: not to repress prejudices, but to shine light on them” (Berlinische Monatsschrift 1785).

As a translator, he brings worlds together. His translation of the Torah, distributed in many editions, teaches Yiddish-speaking children and adults Standard German. His commentary makes scripture accessible and merges traditional with modern knowledge.

As an advisor to reformed schools in Dessau and Berlin, Mendelssohn sets great store in the potential of future generations. In Mendelssohn’s opinion, children should learn both traditional Jewish subjects and modern, practical ones.

In the aftermath of the Thirty Years’ War, different religions and denominations are coming face to face, leaving cracks in their monopoly on truth. On Nov. 11, 1755, a combined earthquake, wildfire, and tsunami destroy the city of Lisbon, claiming as many as 100,000 lives. This devastating catastrophe sparks discussions across Europe about God’s justice or indifference, and not just among Enlightenment thinkers and critics of religion.

Mendelssohn defends the traditional proof of god and the religious laws. As an intermediary between Judaism and German culture, he is at odds with community leaders, who want to preserve tradition and separation. But he also advises Jewish communities when conflicts arise with the authorities.

Mendelssohn merges philosophy, natural religion, and belief in divine revelation. As he sees it, the core of Judaism is identical with universal rational religion.

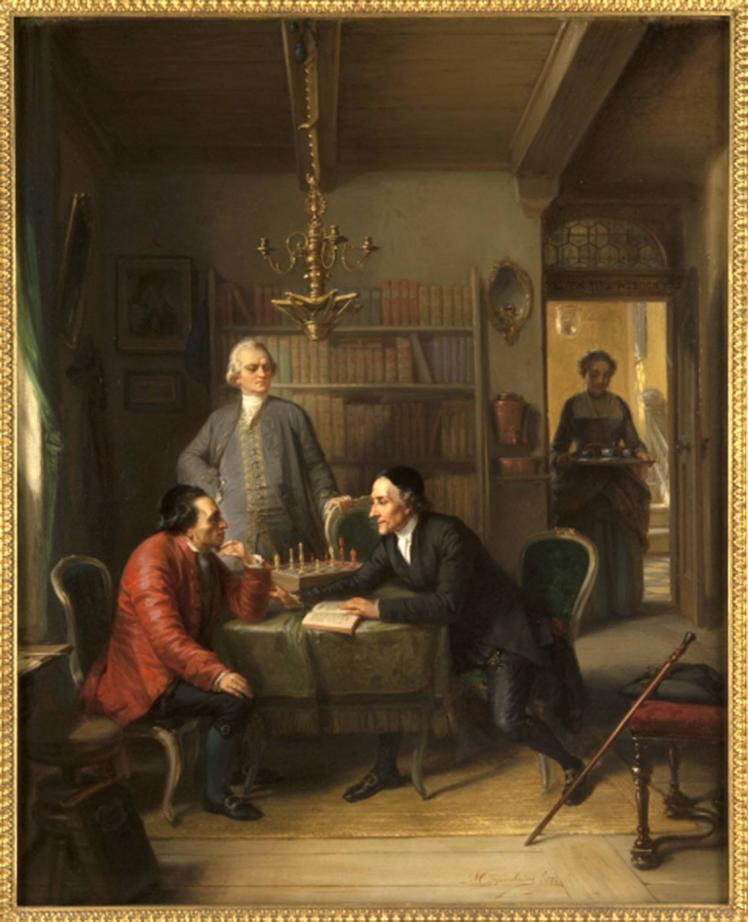

Moritz Daniel Oppenheim, Lavater and Lessing at the Home of Moses Mendelssohn, Frankfurt am Main/Hanau 1856; gift of Vernon Stroud, Eva Linker, Gerda Mathan, Ilse Feiger and Irwin Straus in memory of Frederick and Edith Straus, Magnes Collection of Jewish Art and Life, Bancroft Library, UC Berkeley, Foto: 2013 Sibila Savage Photography

(The encounter depicted above between Moses Mendelssohn and the Swiss theologian Johann Caspar Lavater (1741–1801) never took place as portrayed in the painting – but the theological argument did indeed occur.) Lavater’s book on the table, by Charles Bonnet, claims that Christianity is the one true religion. In his translation, Lavater added a dedication, in which he challenges Mendelssohn to put forward arguments against Christianity, or else convert. The Swiss theologian posits the Jews’ conversion to Christianity as a precondition for the Second Coming of Jesus.

Mendelssohn argues that Judaism is not a missionary religion and makes no claim on exclusivity. Anyone who follows the basic commandments has a share in the World to Come and eternal life.

Of course Mendelssohn declines to convert to Christianity – and wins the moral victory. But the stressful situation makes him gravely ill, jeopardizes his ability to support his family as a merchant, and forces him to withdraw from the public eye for several years.

More in-depth audio description of the painting from our JMB app.

Read along: An Attempted Conversion

Moses Mendelssohn was already famous in his own day. He was the first Jew to take equal part in the philosophical debates of his time. In this painting by Moritz Daniel Oppenheim, he is seated on the left.

When important people visited Berlin, they wanted to meet Moses Mendelssohn. And the Swiss theologian Johann Kaspar Lavater, on the right in the picture, was no exception.

Lavater has a book open on the table in front of him. He is looking at Mendelssohn intensely and is reaching over the table to touch his arm. Mendelssohn looks thoughtful – friendly but distant. The writer Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, a close friend of Mendelssohn, stands between the two and looks on skeptically. In the background a woman, probably Mendelssohn’s wife Fromet, is bringing in a tray with tea.

Oppenheim’s painting is a free interpretation of a debate that didn’t happen in a private living room, but rather in the form of letters, articles and newspapers. From the 1760s onwards, Lavater tried, with great zeal, to convince Mendelssohn to be christened. Though his eagerness to convert Mendelssohn lasted many years, he was not able to convert him.

Advocacy for Human Rights

In the Declaration of Independence of the United States of America, from 1776, thirteen former British colonies declare “unalienable Rights” including the rights to “Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” At the same time, Mendelssohn joins Prussian officials in calling “for a civil improvement of the Jews.” The Jews – the long-oppressed Chosen People – ought to have rights just like everyone else. Everyone is entitled to equality under the law; everyone has countless differences.

“Regard us, if not as brothers and fellow-citizens, at least as fellow-men and fellow-inhabitants of the land. Help us to become better men and better fellow-inhabitants, and let us – as far as the times and the circumstances permit – be partners in enjoying the rights of humanity.” (Moses Mendelssohn, Jerusalem, or on Religious Power and Judaism, Berlin, 1783).

The General Regulations Governing the Jews, issued by the King of Prussia, still deny Jewish residents many rights.

General Regulations Governing the Jews, 1750

“We, Frederick, by God’s grace, King in Prussia, hereby proclaim and decree:That Jews’ rampant proliferation inflicts untold damage not only upon the public, but especially upon Christian merchants.

Extraordinary Schutzjuden [protected Jews] are, however, neither authorized to have a child, nor to marry.

Foreign Jews are not under any circumstances permitted to settle in our lands unless they demonstrably possess ten thousand Reichstaler in assets and bring said sum with them into the country.

The Jews may not engage in any crafts or skilled trades.

In the event that Jews trade in such goods that are prohibited to them, these goods shall be confiscated. ”

Excerpts of the Revised General Privileges and Regulation for the Jewry in the Kingdom of Prussia, April 17, 1750

When Frederick II summons Moses Mendelssohn for a philosophical discussion, equal rights are in reach. Or at least, that was what many German Jews hoped and dreamed. The legend of the two men’s meeting was told and retold with many embellishments: what blunt terms Mendelssohn used in his response to the great King of Prussia!

But the real Old Fritz is an enemy of the Jews. He only supports Mendelssohn as a useful fabric merchant. He blocks his membership in the Academy of Sciences and denies his family any guarantees of residency. The reason he called him to Potsdam was because his guest Baron Fritsche wanted to meet the famous scholar. His Majesty, however, kept his distance.

Tolerance for others is the first step. Mendelssohn defends Jewish religious laws as they do not conflict with government laws. He advocates freedom of conscience and a separation between state and religion.

“Adapt yourselves to the customs and the constitution of the land in which you have been placed; but hold fast to the religion of your fathers too. Bear both burdens as well as you can!” (Moses Mendelssohn, Jerusalem, or on Religious Power and Judaism, Berlin, 1783).

The character of Nathan in Lessing’s play Nathan the Wise also speaks out for tolerance. At the play’s premiere, the character of Nathan is identified with Mendelssohn, but unlike the figure in the play, Mendelssohn does not construe tolerance as minimizing the differences between religions.

X

X

Bust of “Nathan the Whise” by Adolf Jahn, Berlin 1902; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2002/152/0, photo: Jens Ziehe

Aesthetics and Friendship

The notion of “moral sense” arrives in Germany: humans ought to follow their hearts, guided by reason.

The individual gains importance. People seeking genuine relationships no longer see noblemen’s calculated connections as a worthy model. Mendelssohn lives by the new cult of friendship. Unconventionally, he marries for love.

Mendelssohn publishes Letters on Feeling. His theory of art analyzes the profound ways that paintings, music, and theater move us. We cannot appreciate beauty on a purely rational level.

X

X

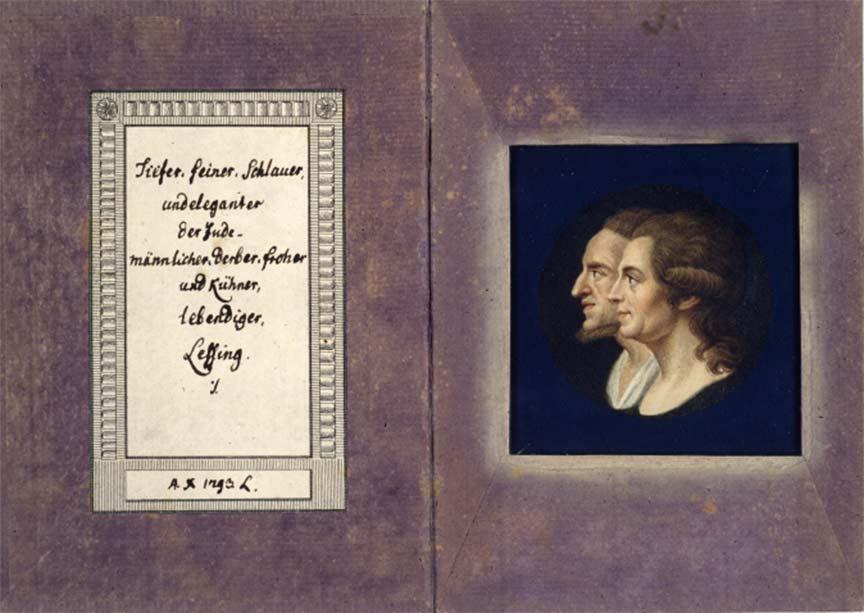

Johannes Pfenniger (1765–1825), Gotthold Ephraim Lessing and Moses Mendelssohn, undated, watercolors; Österreichische Nationalbibliothek Wien

Lessing’s important treatise on art theory, Laocoön, emerges from discussions with Mendelssohn and Nicolai about sensualism, empathy, and how sculpture and poetry affect us. The depiction of the ancient hero and his sons during the agonies of death raises questions about the artistic representation of strong feelings.

What did Enlightenment thinkers mean by “Empfindsamkeit”?

The German word Gefühl – roughly, “feeling” – first emerged in the seventeenth century. In the first half of the 19th century, it still referred to passions, mood shifts, and sensory perceptions. At the time, any emphasis on the emotional side of experience was still associated with confusion and darkness.

During the second half of the century, the word gained more positive connotations. Now, Gefühl – feeling – could help a person recognize the full breadth of beauty in conjunction with reason. The arts were no longer subordinate to the laws and strictures of reason; feeling became an additional factor through which to understand them.

In his aesthetics of artistic reception, in his “doctrine of the affections,” in his analysis of the theater, and with his research into the nature of the soul, Mendelssohn became an advocate of a reflective Empfindsamkeit, or sensibility.

“The sensory experience [Empfindung] of beauty seeks the infinite; the sublime simply stimulates us through the unfathomability that clings to it; indulgence revolts us as soon as it touches the boundaries of satiation. Where we see boundaries that are not to be exceeded, the imagination feels as though forged in shackles, and the very skies seem to enclose our existence in exceedingly tight spaces: this is why we so enjoy letting our imagination run loose and extending space’s boundaries into the infinite.” (Moses Mendelssohn in Phaedon)

The sensory sphere of Empfindsamkeit – at first labeled Zärtlichkeit (“tenderness”) – fell into disrepute, and was eventually dismissed as a fad for Empfindelei (a contemptuous word, something like “sensitive-ery”) and more generally as sentimentality. When sensibility is cultivated on a surface level, today we might call it oversensitivity, melodrama, or mushiness.

In Correspondence on Tragedy, Mendelssohn analyzes sympathy and the sublime as effects of theater. He draws in particular on his own translation of Shakespeare’s “To Be or Not to Be” monologue. He is “completely enraptured” by J. F. Brockmann’s performance of Hamlet in Berlin.

It takes Mendelssohn ten years to complete his translation of the Psalms, some of which are set to music by contemporaries. In his view, music combines and transforms human passions, discordance, and sensuous pleasure into the “magical power of harmony.”

“Divine art of sound! You are the only one who surprises us with all kinds of pleasure! What sweet confusion of perfection, sensuous pleasure, and beauty! The imitations of human passions, the artful combination of discordant tones: sources of perfection! The simple proportions of vibrations: a source of beauty! The tensions of the vessels of the nerves harmonizing with every string: a source of sensuous pleasure!” (Moses Mendelssohn)

Regarding the art of painting, Mendelssohn comments on the “rose of Huysum,” for example. According to Mendelssohn, a single “rose by Huysum” allows us to recognize the artist’s spirit, whose perfection gives us more pleasure than the painted flower’s resemblance to the real one.

X

X

Jan van Huijsum (1682–1749), Bouquet of Flowers with Snails, around 1724, oil on canvas; Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum Braunschweig, Kunstmuseum des Landes Niedersachsen

Between Immortality and Frailty

Is Homo sapiens a machine? Do the body and soul have a workable arrangement? Mendelssohn’s bestselling book Phaedon: Or, On the Immortality of the Soul addresses the questions of his troubled contemporaries.

As he sees it, God dictates each person’s lot in life, and it’s up to individuals to rise above their own challenges. Self-fulfillment through good deeds brings happiness and changes society for the better.

X

X

Daniel Nikolaus Chodowiecki (1726–1801), The Equality of All Classes in Death, Berlin, 1770, etching; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2021/89/0, photo: Roman März

How did Mendelssohn use the word Tugend (virtue)?

This German word, which in today’s common usage is often associated with self-denial, prudishness, or bigotry, had the meaning of suitability and efficiency in Mendelssohn’s day.

To find corresponding positive concepts today, you might turn to power, energy, and values. In the late twentieth century, the shift in meaning and the crisis of the concept of Tugend (virtue) within German culture is evident in skepticism towards what are seen as Prussian, middle class, or “secondary virtues”: diligence, faithfulness, obedience, a love for order, etc.

In ancient times, the classical core virtues were considered to be wisdom, justice, courage, and moderation. According to Aristotle, who laid important cornerstones of Western Christian theology, virtue leads to a happy life, to joy. Based on the Ten Commandments and the beatitudes from Jesus’s Sermon on the Mount, medieval Christians developed a catalog of seven virtues (humility, charity, chastity, patience, temperance, kindness, and diligence). These were supplemented by the divine or theological virtues of faith, hope, and love.

The Enlightenment thinkers were primarily interested in the ethical virtues, much more so than virtutes intellectuales. Some of them no longer attributed these to religion and divine love, but instead saw them as a product of rules and law-abiding. In this view, virtue consists of an orientation towards the collective good, service to humanity, neighborly love, and involvement in the universal diffusion of happiness.

In Mendelssohn’s view, the purpose of all virtue is to perfect one’s own inner and outer condition and that of one’s fellow human beings to the greatest extent possible. Harmful tendencies and moral obtuseness can be overcome by practicing virtuous behavior.

According to Mendelssohn human perfection, ordained by God, begins in the womb and does not end with death. Humans are “created for immortality” and cannot imagine “true annihilation.”

Mendelssohn’s Phaedon is published in numerous translations and editions. Mendelssohn revisits the dialogues of the condemned Socrates, recorded by Plato, and applies them to questions about the meaning of life, Berlin/Stettin, Nicolai: 1767; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession VII.5. Mende 275

Mendelssohn stutters, has a hunchback, and is often ill. He suffers from a nervous disease for years, and is in constant need of doctors’ care and spa treatments. He dies at fifty-six.

The radical link between immortality and his fragility is both fascinating and disconcerting. His brilliance in the face of his experiences with disability and discrimination is a further credit to his life’s work.

Mendelssohn as a Celebrity

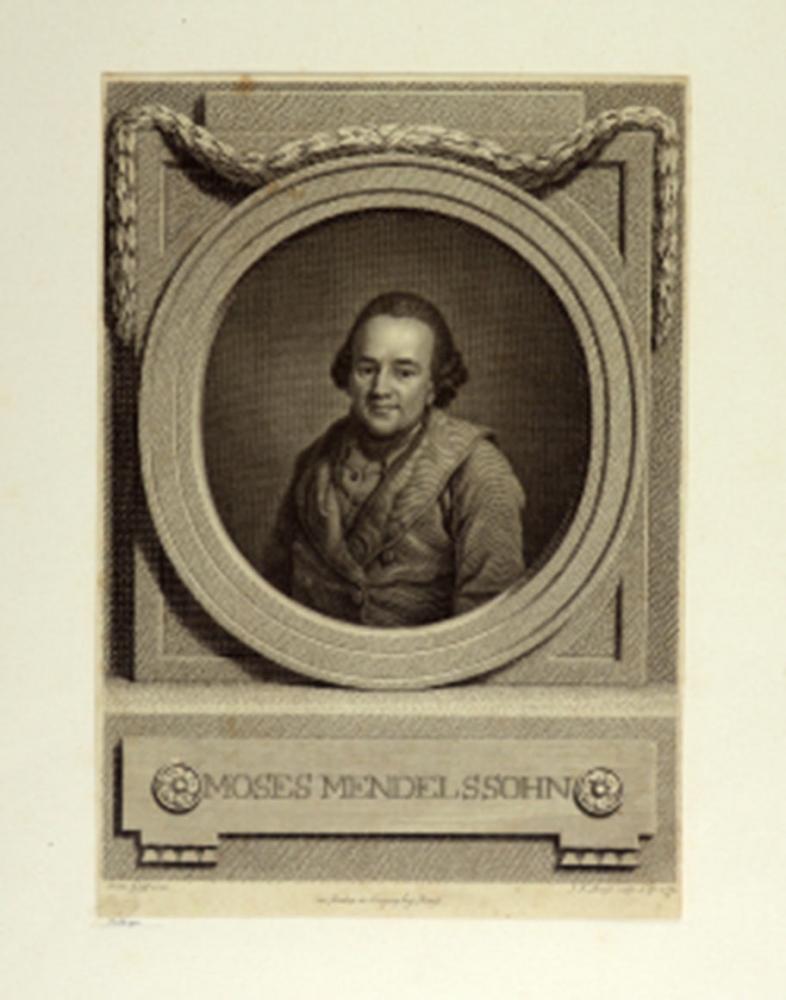

New ideas are not conveyed through reading alone. The public wants to see its authors’ faces. Countless portraits are circulated. Images both project and perpetuate preconceived notions.

During his lifetime, the portrayals of Mendelssohn – paintings, engravings, and medallions – varied tremendously. The earliest miniature, from 1767, depicts the young bestselling author as a Jewish scholar. A bust sculpted the last year of his life hails a new Socrates. The effect ranges from spiritual to charismatic to naturalistic. Images of Moses Mendelssohn were unusually widespread throughout Europe – in the same way that Albert Einstein’s image has become part of present-day popular culture.

Which Moses do you prefer? In the marketplace of critical opinions, everyone is hunting for their own likeness.

From the Picture Factory

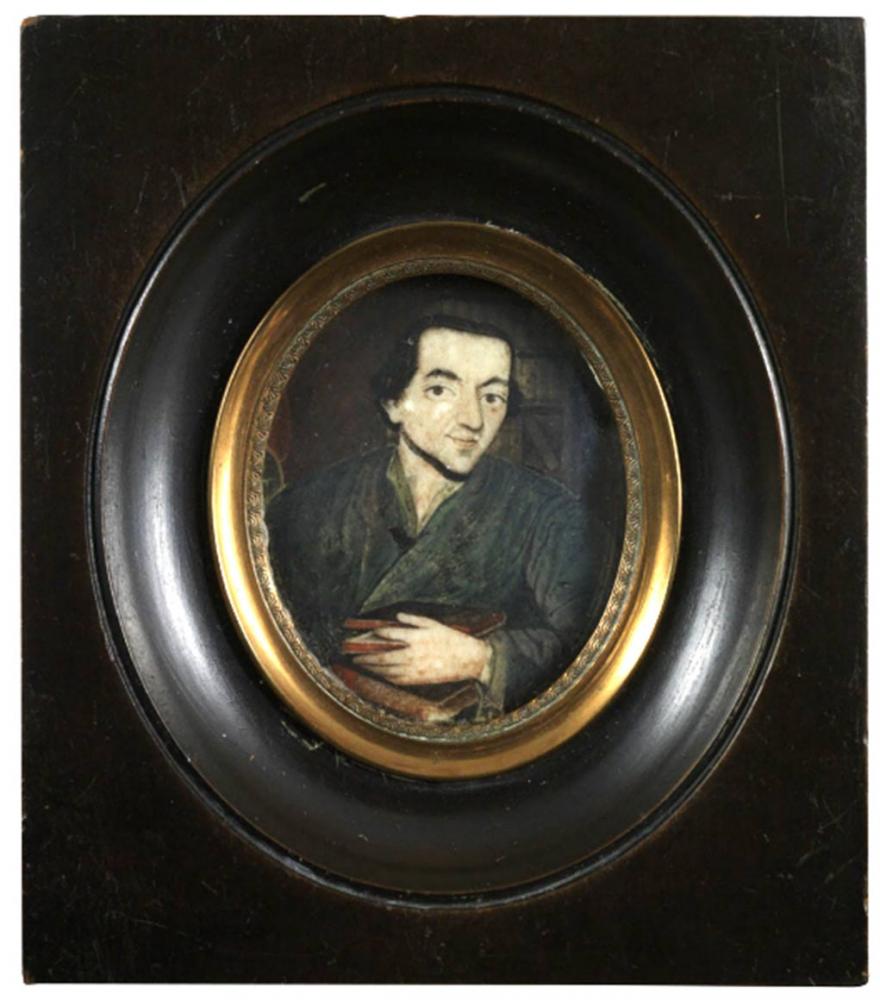

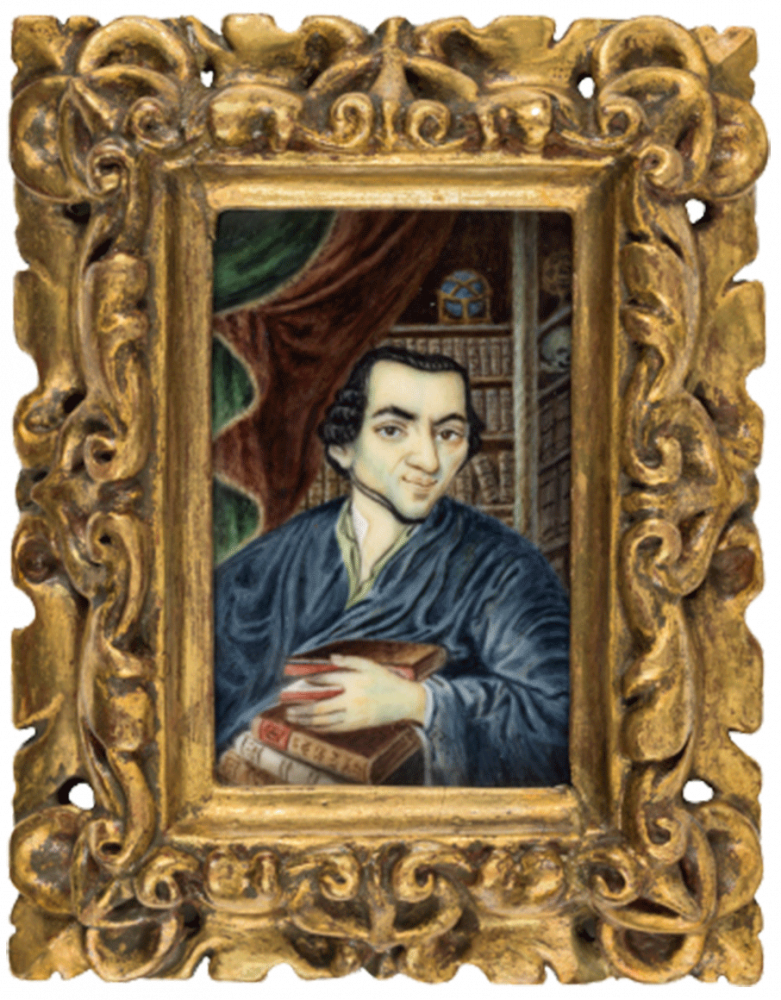

In the same year Phaedon is published, probably a Jewish artist from Hamburg creates a miniature portrait of Mendelssohn, of which multiple copies are made. Other portraits were also distributed as engravings and miniatures

Probably Elimelech Pilta ben Schimschon Rofe, miniature portrait of Moses Mendelssohn, after 1767, gouache on horn or ivory; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2001/357/0, photo: Jens Ziehe

Probably autograph variant of the miniature portrait by Elimelech Pilta ben Schimschon Rofe, after 1767, gouache on ivory; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2020/107/0, photo: Roman März

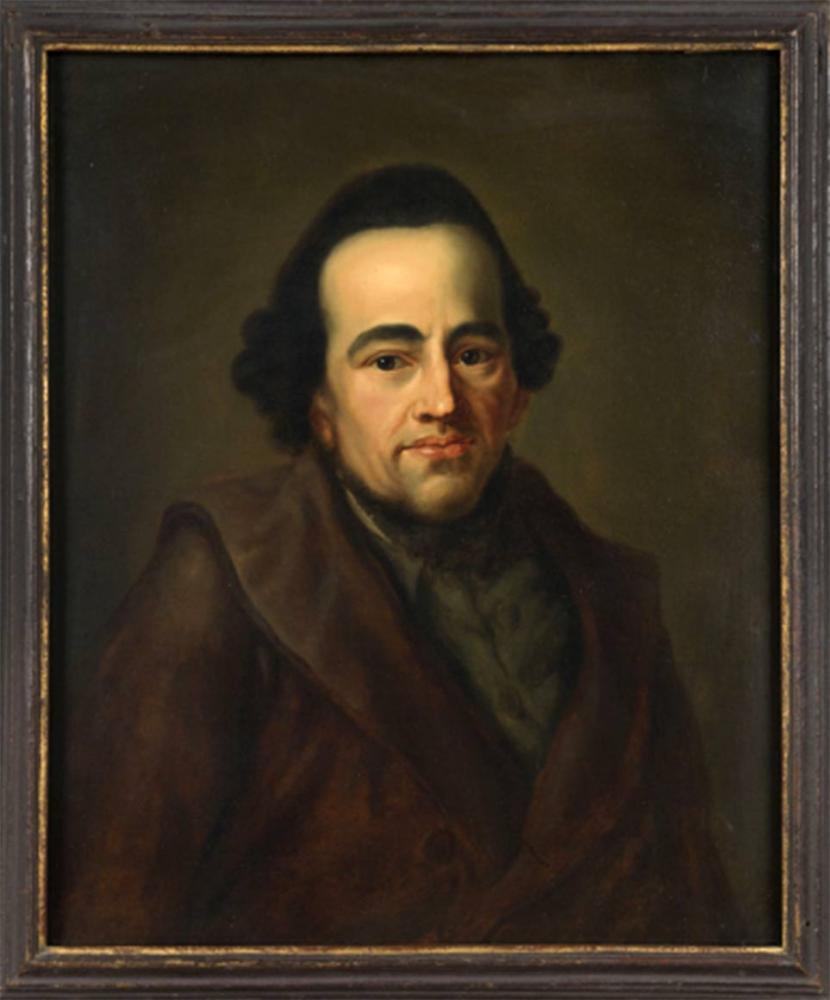

At the peak of the Lavater dispute, Leipzig bookseller Philip Erasmus Reich commissions painter Anton Graff to paint a portrait for his “friendship gallery.” This portrait, today in Leipzig, is disseminated as replicas, copies, and prints.

Copy after Anton Graff (1736–1813), portrait of Moses Mendelssohn, after 1771, oil on canvas; Mendelssohn-Gesellschaft e.V. Berlin, on loan from a private collection

Johann Friedrich Bause (1738–1814) (after Anton Graff), portrait of Moses Mendelssohn, Leipzig, 1772, engraving; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2020/123/0, photo: Anne Krause

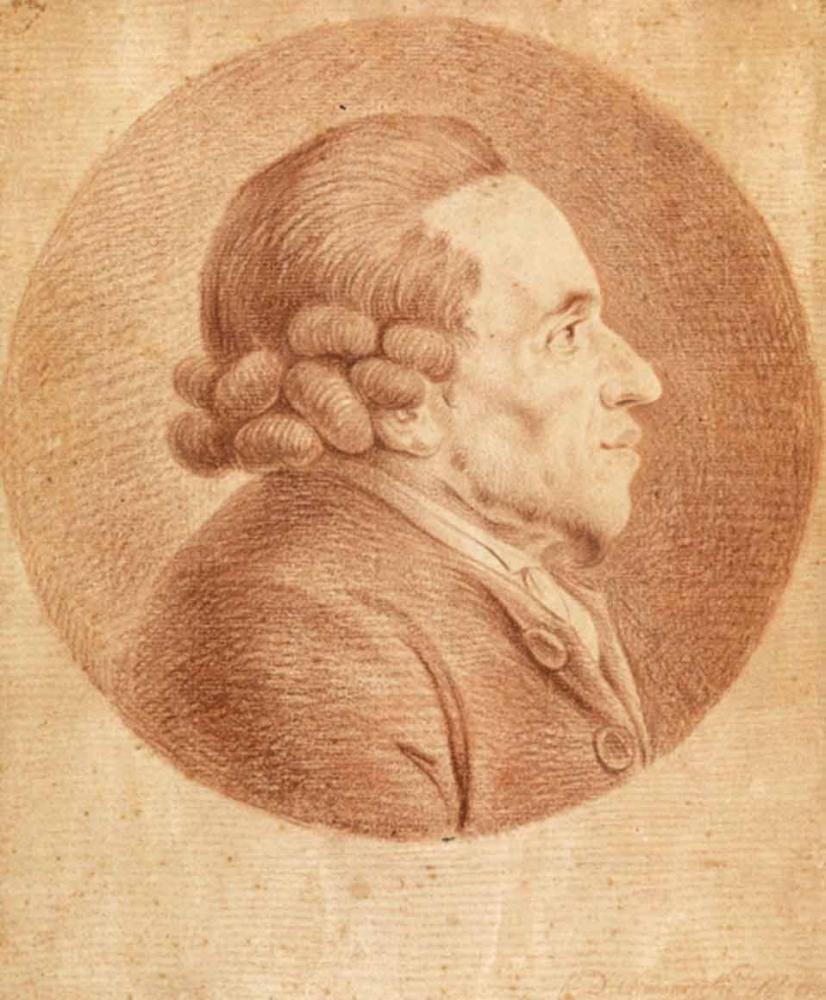

Chodowiecki develops an idealized portrait based on a cartoon-like sketch. The drawing is reproduced using the counterproofing technique. It serves as the basis for Abramson’s medallion and numerous engravings.

Daniel Nikolaus Chodowiecki (1726–1801), portrait of Moses Mendelssohn, Berlin, around 1775, red chalk; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2013/125/0, photo: Jens Ziehe

Further information on this object can be found in our online collections (in German)

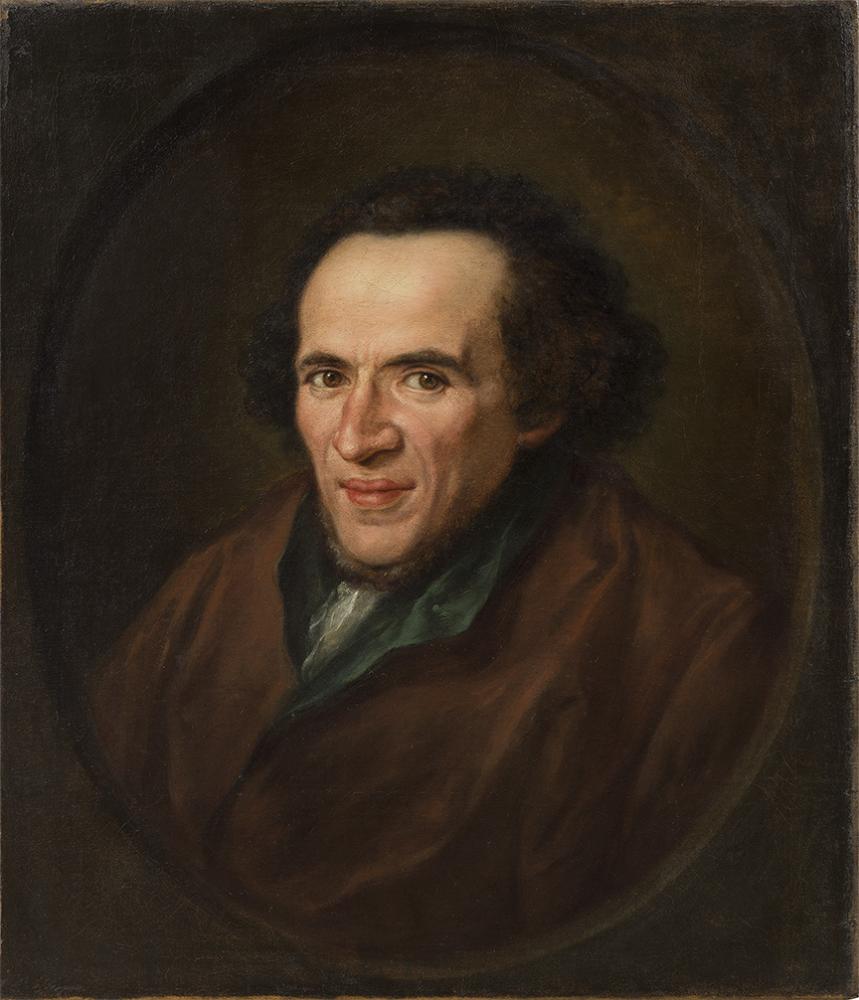

Johann Christoph Frisch, who has also made portraits of Marcus Elieser Bloch, Marcus Herz, and Isaac Daniel Itzig, paints what will be the most frequently reproduced of these portraits in 1783, the same year as the wedding of Mendelssohn’s daughter Dorothea and the release of Jerusalem.

Johann Christoph Frisch (1738–1815), portrait of Moses Mendelssohn, Berlin, 1783, oil on canvas; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2013/355/0, photo: Roman März

Further information on this painting can be found in our online collections (in German)

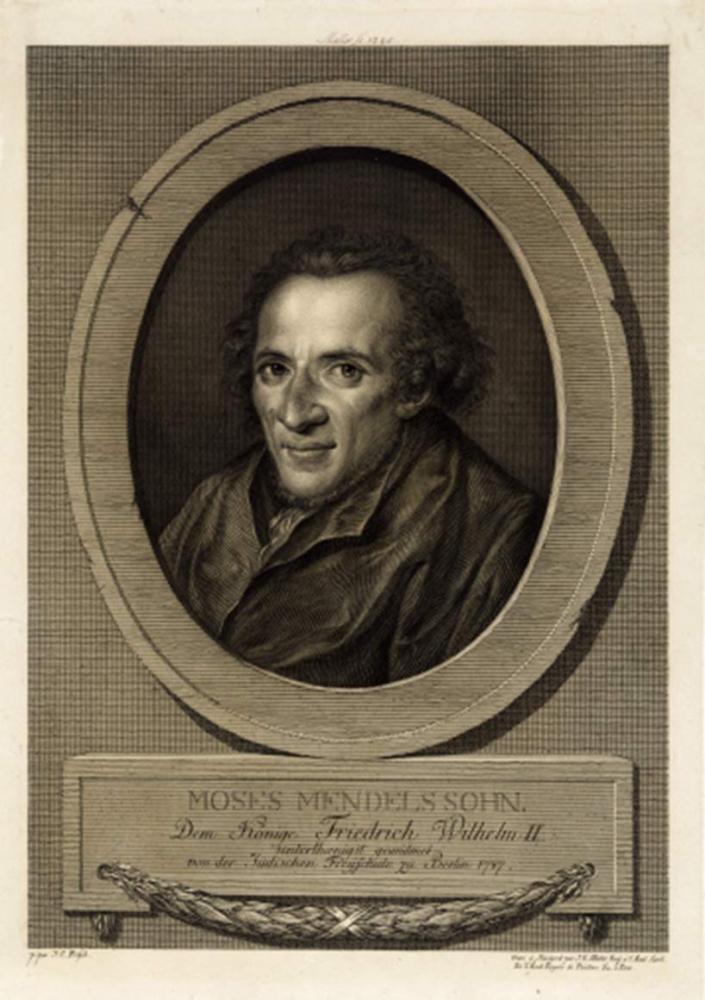

Johann Gotthard Müller (1747–1830) (after Johann Christoph Frisch), portrait of Moses Mendelssohn, Stuttgart, 1786/87, engraving; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession GDR 64/1/0, photo: Roman März

Further information on this object can be found in our online collections (in German)

A substitute for a bust or an artistic experiment? This portrait belongs to Mendelssohn’s admirer Dorothea of Courland, who may also have commissioned it. The artist paints portraits of the nobility in Courland (in today’s Latvia) as well as Berlin’s Jewish elite.

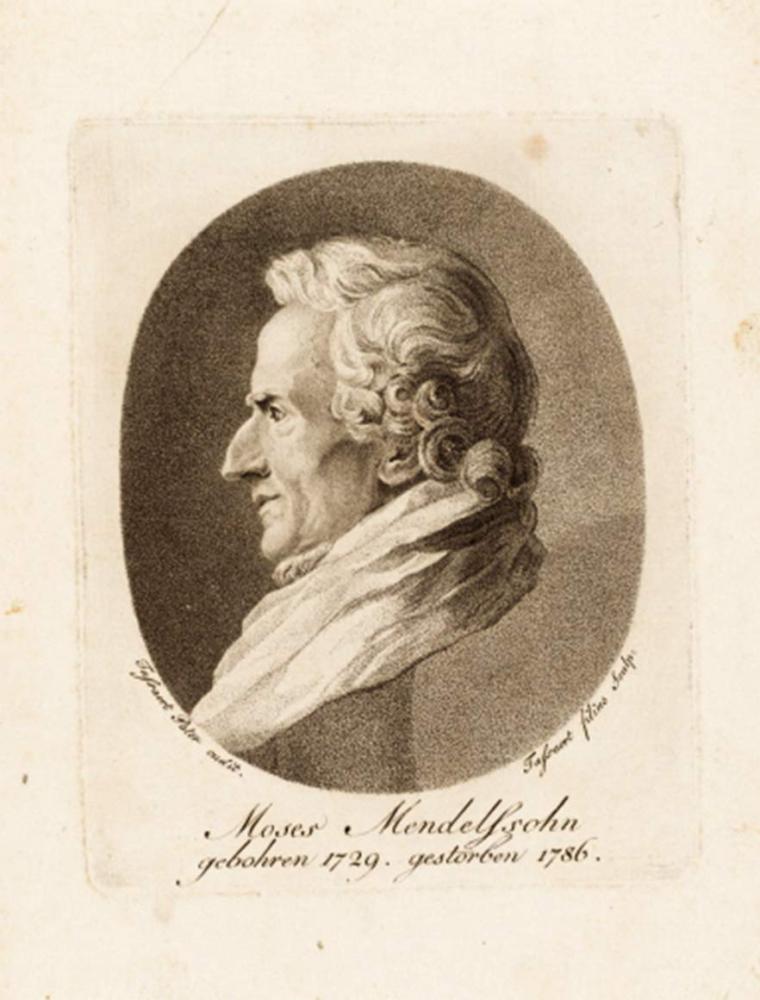

Jean Joseph François Tassaert (1765–1825) (after Jean Pierre Antoine Tassaert), portrait of Moses Mendelssohn, after 1786, engraving; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2018/129/0, photo: Roman März

Further information on this object can be found in our online collections (in German)

Johann Gottfried Schadow (1764–1850) (after Jean Pierre Antoine Tassaert), portrait of Moses Mendelssohn with Phaedon, Psalms, and Jerusalem, around 1786/87, etching; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 1999/106/0, photo: Jens Ziehe

Further information on this object can be found in our online collections (in German)

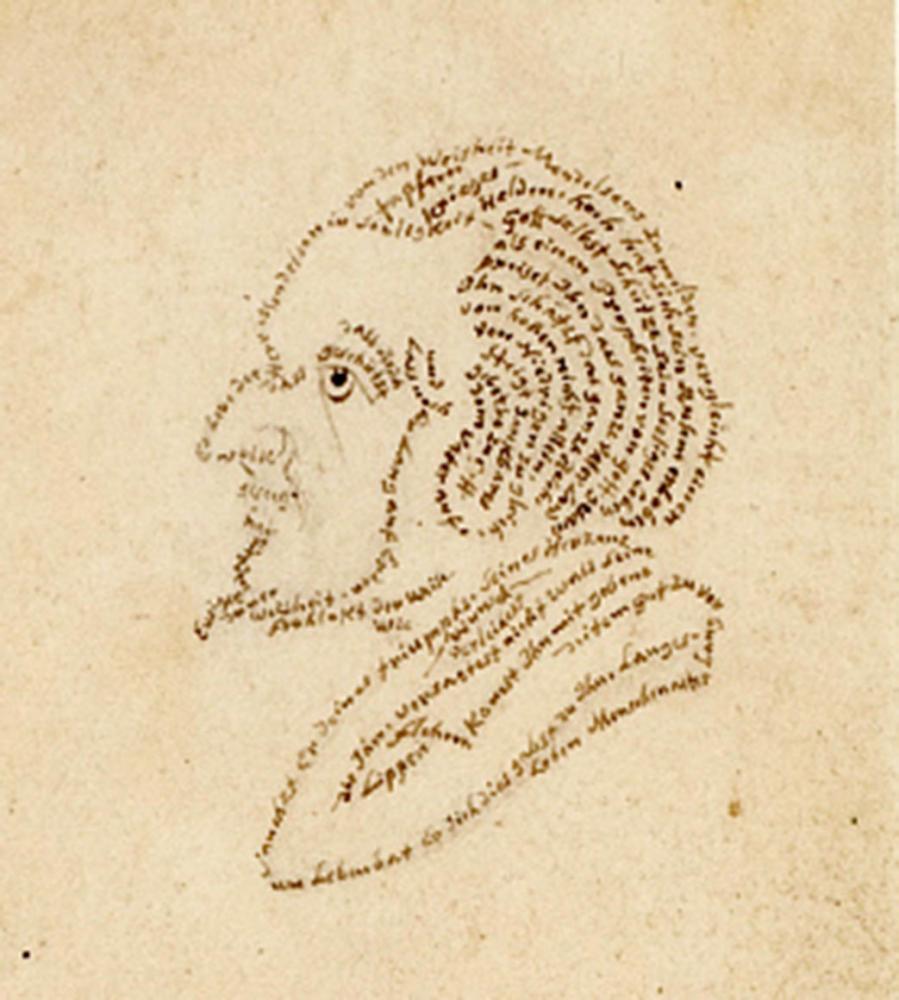

Unknown (after Johann Christoph Frisch), Micrographic Portrait of Moses Mendelssohn, after 1778, ink on paper; CC-BY-SA Herzog August Bibliothek Wolfenbüttel

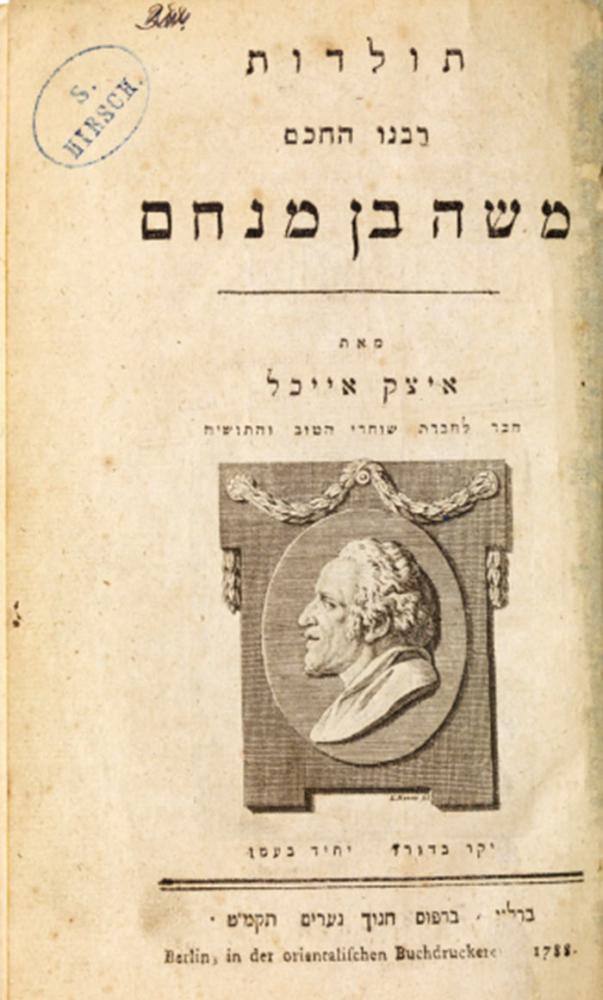

Isaak Abraham Euchel (1756–1804), Toledot rabbenu he-hakham Moshe Ben Menahem (The Life of Our Rabbi the Wise Man Moses Mendelssohn), engraving by Eberhard Siegfried Henne (after Johann Christoph Frisch), 1784, Berlin, Orientalische Buchdruckerei: 1788; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession IV. Mende 1964, photo: Jens Ziehe

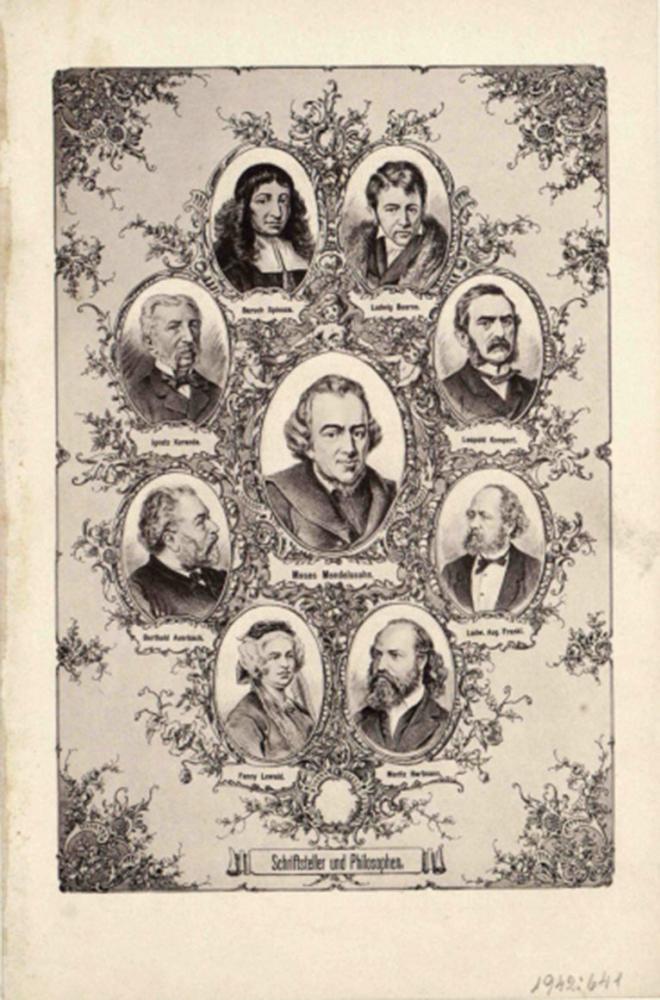

Jews in the nineteenth century, liberal and traditional alike, venerate Mendelssohn. Moses Mendelssohn surrounded by Spinoza, Ludwig Boerne, Leopold Kompert, Ludwig August Frankl, Moritz Hartmann, Fanny Lewald, Berthold Auerbach, and Ignatz Kuranda.

Unknown, Moses Mendelssohn surrounded by writers and philosophers, around 1900, lithograph; Österreichische Nationalbibliothek Wien, PORT_00134974_01

When building roads to the future, everyone designs the heroes they desire. The whole Jewish community walks in Mendelssohn’s funeral procession, including members of the royal court. Soon enough, various factions disagree about his legacy.

For Haskalah activists, he is the Enlightenment thinker. For the Orthodox, he is the pious follower of the commandments. For shtetl residents, he is the Torah translator. For the patriotic, he is the “Moses of the German Jews.”

With support from Mendelssohn’s descendants, the preparation of an anniversary edition of his collected writings is initiated in 1929 to commemorate his two-hundredth birthday. In 1938, the Gestapo destroys all but a few copies of the most recent volume. The project was resumed in 1972 and is scheduled to be completed in 2023.

Variations on Immortality

David Rosenberg, Memorial for Moses Mendelssohn’s hundredth birthday, Brussels, 1829, lithograph; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2007/235/0, photo: Roman März

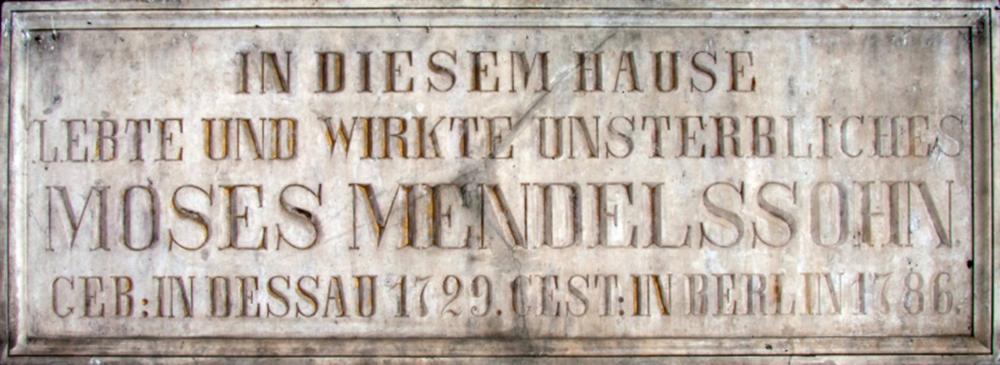

This memorial plaque was affixed to Mendelssohn’s former home on Spandauer Straße 68. One of the earliest tributes to a commoner in any public space.

Unknown, Memorial plaque for Moses Mendelssohn, Berlin, 1829, marble; Stiftung Neue Synagoge Berlin – Centrum Judaicum, Berlin, photo: Anna Fischer

Otto Illemann (1869–1929), Medallion of Moses Mendelssohn, Berlin, 1929, bronze, patinated; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2005/10/1, photo: Roman März

Further information on this object can be found in our online collections (in German)

Special-edition postage stamp marking Moses Mendelssohn’s 250th birthday in 1979, designed by Reinhold Gerstetter, issued by: West German Federal Ministry of Finance; Jewish Museum Berlin, 2000/138/2, gift of Susanne Götze, photo: Jens Ziehe

Further information on this object can be found in our online collections (in German)

For permission to use this image, contact LB5@bmf.bund.de.

Unknown, Goblet bearing a portrait of Moses Mendelssohn, Northern Bohemia, around 1835 (goblet), 1886 (engraving, signed K.B.), glass; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2019/53/0, photo: Roman März

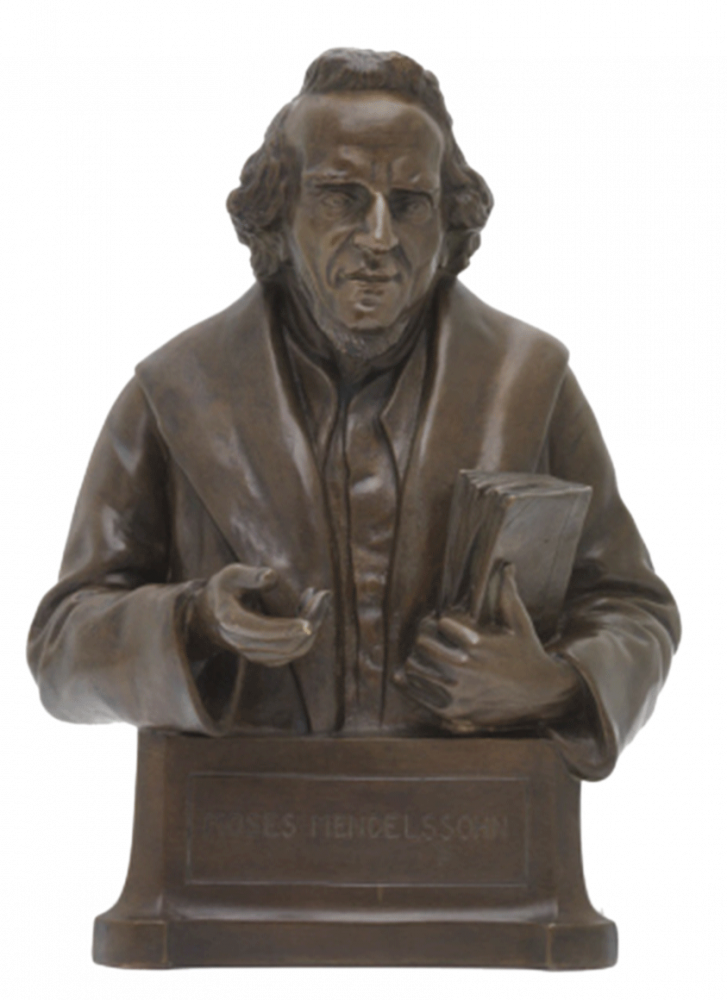

Fürstenberg Porcelain Manufactory, Bust of Moses Mendelssohn, 2006, recast using the original mold from 1785–1790, porcelain; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession Deko/61/0, photo: Jens Ziehe

Jacob Plessner (1871–1936), Bust of Moses Mendelssohn, 1929, cast after the model of 1909, bronze, patinated; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2014/374/0, photo: Jens Ziehe

Is it true that the 14-year-old Moses Mendelssohn walked all the way from Dessau to Berlin on foot, and then even had to take a further detour around the city walls because Jews were only allowed to pass through the city’s northern gate, Rosenthaler Tor?

Given the length of the journey, it is quite unlikely that the stereotype of the “wandering Jew” applies to Mendelssohn in this case. There is also no evidence that Rosenthaler Tor was the only city entrance open to Jews at the time. It is more likely that Moses Mendelssohn traveled from Dessau by stagecoach, as was common at the time. When he arrived, he would have answered the gatekeeper’s questions and paid a special tax that applied to Jews – then entered Berlin through its southern entrance, Hallesches Tor.

The graphic novel Moishe by typex explores these and other legends.

In the years after Mendelssohn’s death, attitudes towards him and his ideas polarize. In the history of philosophy, Mendelssohn is treated as a “popular philosopher,” overshadowed by Immanuel Kant. Marx dismisses him as wishy-washy. Zionists blame him for assimilation. Ultimately, the Nazis demonize him.

Perhaps it is time for a re-evaluation. When contemplating the questions of our own time, how can we build on the utopia of the Enlightenment and its eagerness for dialogue?

Citation recommendation:

Jewish Museum Berlin (2022), Moses Mendelssohn. A Deep Dive into Themes of the Exhibition “We dreamed of nothing but Enlightenment”.

URL: www.jmberlin.de/en/node/8663

Exhibition “We dreamed of nothing but Enlightenment” – Moses Mendelssohn: Features & Programs

- Exhibition Webpage

- “We dreamed of nothing but Enlightenment” – Moses Mendelssohn: 14 Apr to 11 Sep 2022

- Publications

- “We dreamed of nothing but Enlightenment” – Moses Mendelssohn: Exhibition catalog, 2022, bilingual in German and English

- Moishe. Six Anecdotes from the Life of Moses Mendelssohn: Graphic Novel by Typex, 2022, English edition, with reading sample for download

- Moische. Sechs Anekdoten aus dem Leben des Moses Mendelssohn: Graphic Novel by Typex, 2022, German edition, with reading sample for download

- Digital Content

- Current page: Moses Mendelssohn and His Time: Online feature, 2022

- Mendelssohn Discourses: Media Revolution – Publicity, Celebrity, A Flood of Images: Video recording with Frederek Musall, Caspar Battegay, and Shmuel Feiner, 2022, in Englisch

- Mendelssohn Discourses: Enlightenment: Fake News, Sentimentality, Reason: Video recording with Carolin Emcke, Hannah Peaceman, Frederek Musall, Inka Bertz, and Thomas Lackmann, 2022

- Based on a True Story: Interview with Typex, comic artist and author of Moishe, 2022

- See also

- Moses Mendelssohn, Philosopher

- Haskalah/Enlightenment

- Moses Mendelssohn: More objects in our online collections, in German

X

X