Golem

From Mysticism to Minecraft

It is neither human nor animal nor machine. A golem is shaped out of an inanimate material and brought to life by magic. Originally, creating a golem was a way for medieval Jewish mystics to come closer to God.

For 200 years, legends have gathered around it. The golem assumes the role of an assistant on a specific mission. In these stories, the soulless, artificial helper often runs amok and becomes a danger to its creator.

Golem Souvenir from Prague, 2015; Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Jens Ziehe

Today, we encounter the golem in many media, from visual art to film to computer games. It can also symbolize any human creation that serves a positive purpose but has the potential to escape our control. From cyborgs and atomic bombs to political movements, the golem has many faces.

The Legend of the Golem of Prague

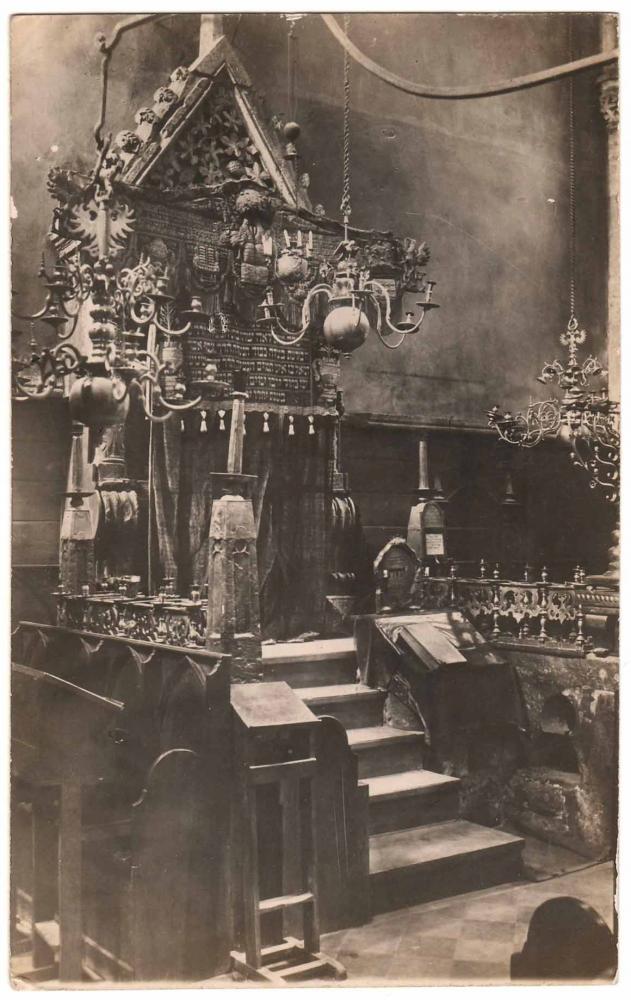

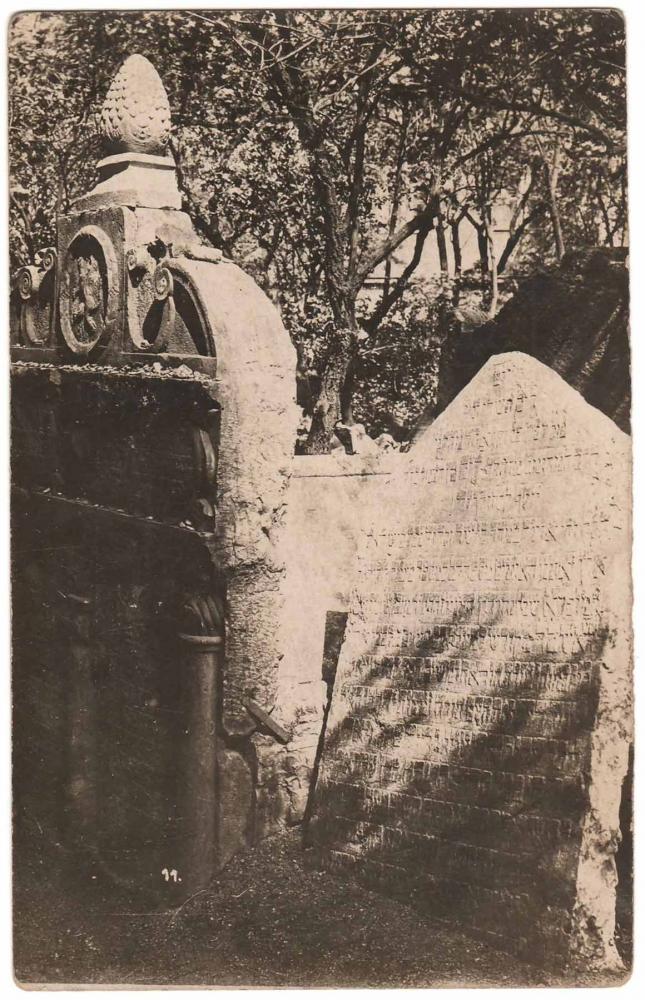

"Great men were once able to perform great miracles," begins the short story "The Golem," written by the author I. L. Peretz in 1890. In his narrative, Peretz retells the best-known version of the golem legend, which takes place in Prague and revolves around the studious Rabbi Loew. The rabbi performs the great miracle of bringing a clay golem to life – by placing a magic word, the shem, in its mouth. Once brought to life, the golem is strong and protects the Jewish ghetto. It also performs all sorts of physical labor for its creator. But one day the golem flies in a rage, smashing buildings, flinging boulders, and uprooting trees. Rabbi Loew pulls the shem out of the golem's mouth and the creature falls to the ground, dissolving into dust. Frightened by this turn of events, the rabbi resolves never again to create such a dangerous servant. To this day, the dusty remains of the golem are said to be located in the closed-off attic of the Old New Synagogue in Prague.

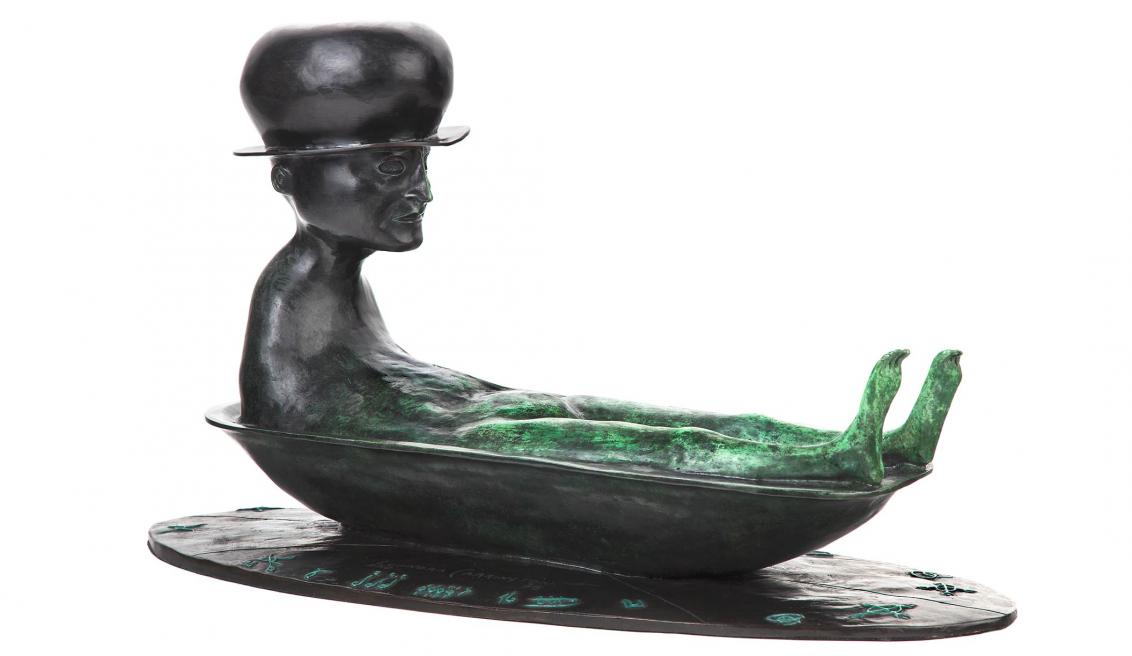

The artist Leonora Carrington created a number of surrealist works with a recurring motif of Rabbi Loew bathing as he contemplates his creation of artificial life. Leonora Carrington, El bañista, 2010, private property Mexiko; photo: Francisco Kochen

The Historical Setting of the Story: Jewish Prague

The interior of the Old New Synagogue in Prague, photograph by Zikmund Reach around 1900; Fostin Cotchen Collection

Legend or True Story? How the Golem Came to Prague

The golem legend was not always associated with the city of Prague. Other alternative golem narratives are set in Israel, Spain, or Poland. In the nineteenth century, one story telling of how Rabbi Eliyahu of Chełm in Poland creates a golem was just as popular as the Prague legend. However, around 1900, it was firmly displaced by the Prague version, which takes place in the sixteenth century under the reign of Rudolf II.

Rabbi Yehudah ben Betzalel Loew, who is assigned the role of the magical golem creator, was a historical figure. He was not known as a mystic, however. Rather, the atmosphere in Prague during Loew's lifetime offered a fitting backdrop for a story about a human attempt to create artificial life. Rudolf II, king of Bohemia, was a patron of science, the arts, mysticism, and the occult, as is evident from his cabinet of curiosities.

During Rabbi Loew's lifetime, Rudolf II (1552–1612) sat on the throne in Prague. As a patron, the king supported many scholars and artists, including Giuseppe Arcimboldo. In this painted portrait Arcimboldo immortalized his benefactor as the Roman god Vertumnus with his face composed of various vegetables, fruits, and plants. Giuseppe Arcimboldo, Vertumnus, 1591, Skokloster Castle; photo: Erik Lernestål

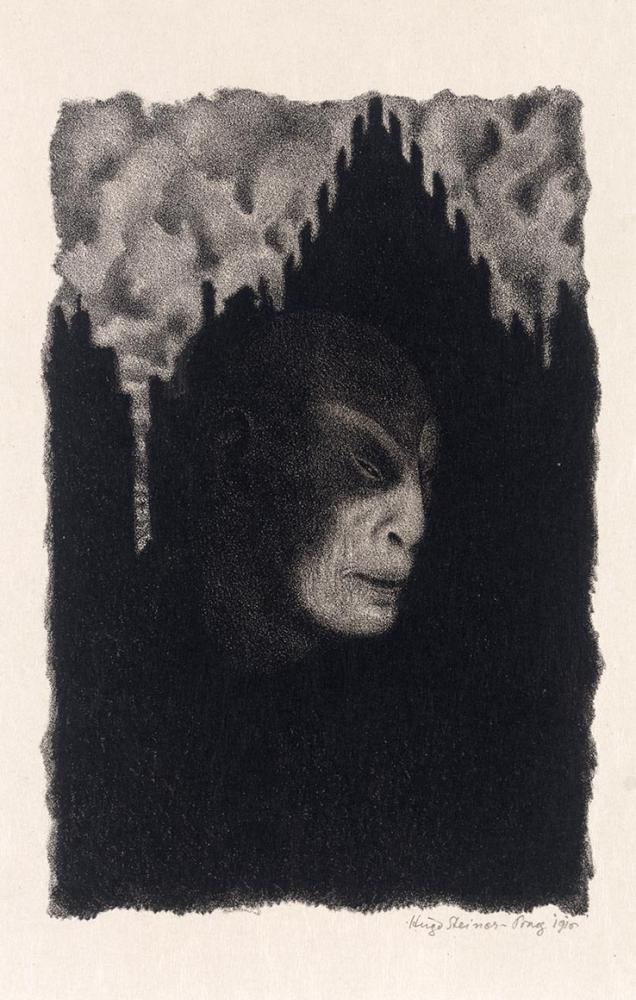

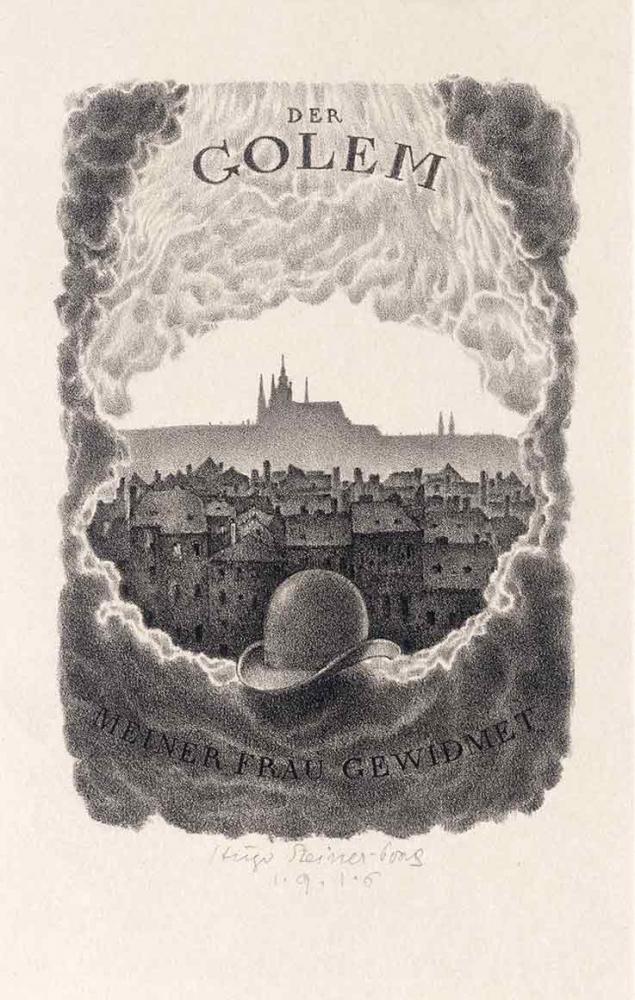

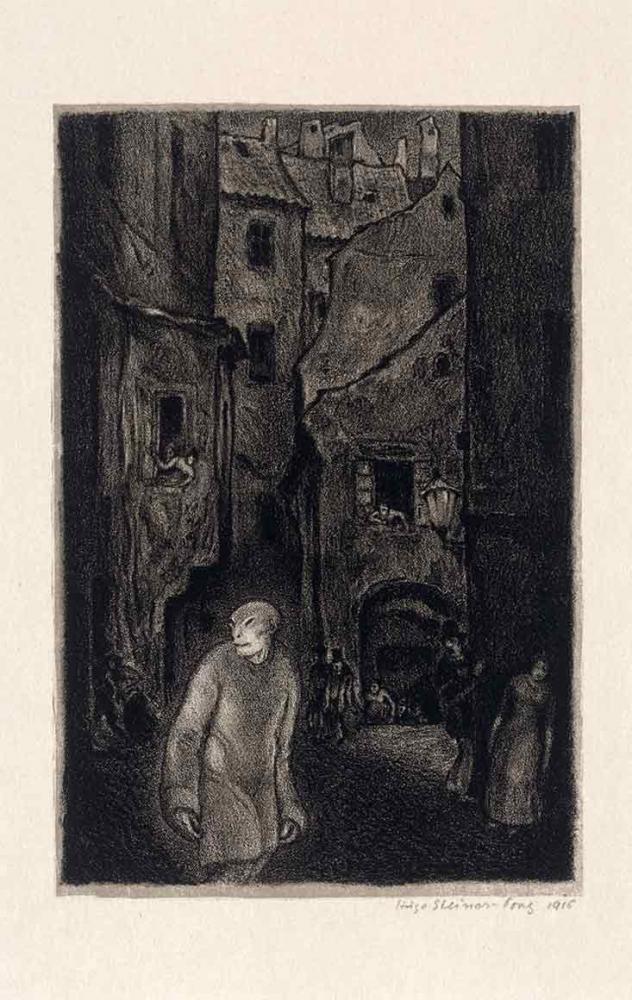

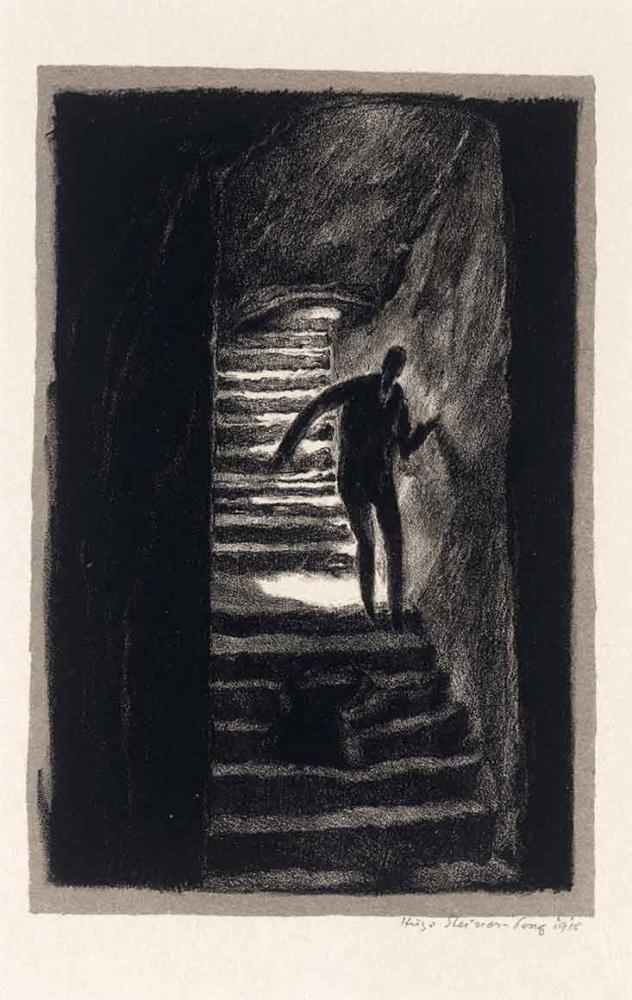

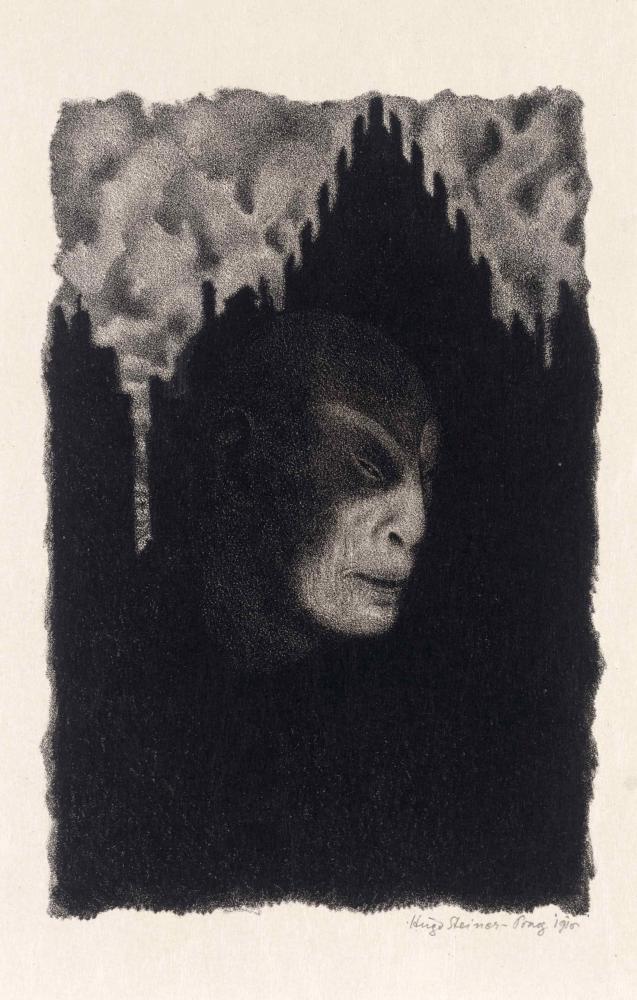

The Golem by Gustav Meyrink

Shortly before the First World War, Gustav Meyrink wrote the novel The Golem. Meyrink's golem account caught the spirit of the age and was a resounding success. It popularized the golem figure and its native city of Prague among a broad non-Jewish public. The novel is a piece of grimly psychedelic, turn-of-the-century crime fiction. It assigns only a marginal role to the golem, a ghostly creature that appears in the dark alleys of the Prague Jewish Quarter once every thirty-three years. The spooky lithograph illustrations were made by the artist Hugo Steiner-Prag.

Illustrations by Hugo Steiner-Prag for the novel The Golem by Gustav Meyrink

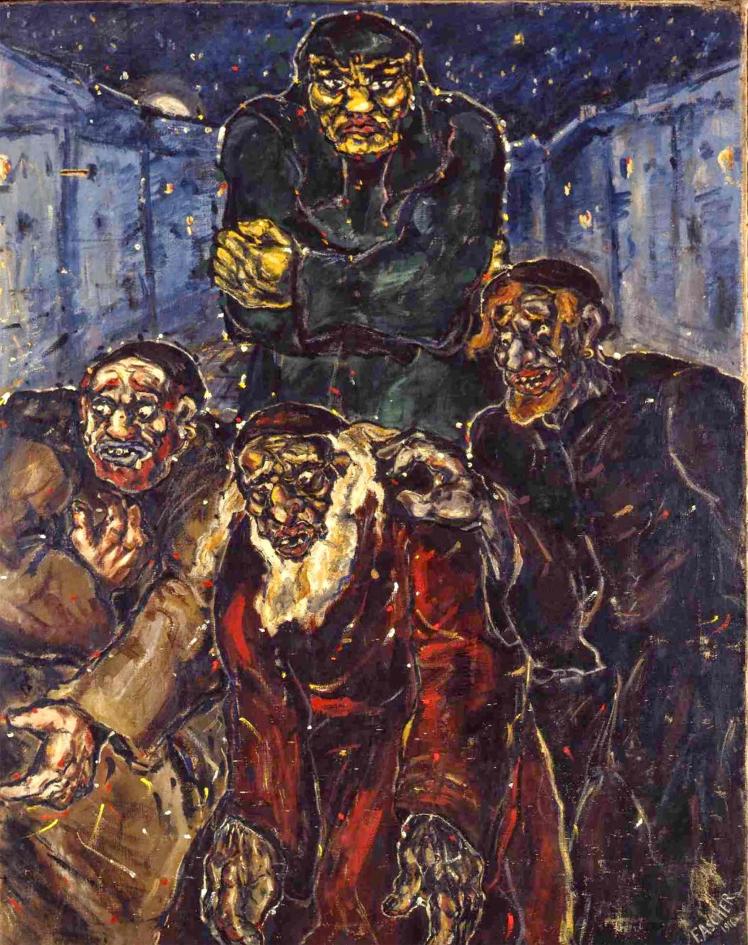

Gustav Meyrink’s detached descriptions of the golem and the residents of Prague’s Jewish quarter make use of anti-Semitic stereotypes. Hugo Steiner-Prag based his illustrations on Meyrink’s characterization of the golem as a “Mongolian type” and created a physiognomy that differed markedly from the golems that emerged in later periods.

The Golem from the portfolio The Golem – Prague Fantasies by Hugo Steiner-Prag, 1916; Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Jens Ziehe

Cover of the portfolio The Golem – Prague Fantasies by Hugo Steiner-Prag, 1916; Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Jens Ziehe

The Appearance of the Golem from the portfolio The Golem – Prague Fantasies by Hugo Steiner-Prag, 1916; Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Jens Ziehe

The Way to Horror from the portfolio The Golem – Prague Fantasies by Hugo Steiner-Prag, 1916; Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Jens Ziehe

The Golem as a Classic Silent Movie

Actor and director Paul Wegener retold the story of the golem in the same period as Gustav Meyrick. He brought the legend to the silent screen three times in just five years: 1915, 1917, and 1920. In all three films, Wegener played the role of golem himself, leaving a lasting mark on the visualization of the figure with his character's striking silhouette. Wegener achieved world renown for his final golem film, made in 1920, The Golem: How He Came into the World. This classic silent film was a milestone in the horror genre.

Hans Poelzig and Marlene Moeschke were responsible for the art direction.

In 1920, Paul Wegener hired his friend the architect Hans Poelzig to design the sets for the third golem film. Rapidly sketching his ideas, Poelzig developed a novel, strikingly anthropomorphic vocabulary of shapes for the sets. In Wegener's words, what Poelzig's "urban poetry" produced was "not reality, but the atmosphere in which the golem breathes." While Poelzig created drawings of the Golem's movie set, his partner, the sculptor Marlene Moeschke, designed the interiors, props, and costumes. Later she also sculpted the physical sets.

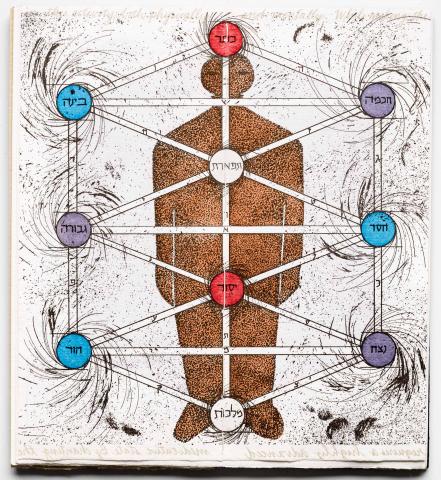

The Golem in Jewish Mysticism

The question of whether humans can create artificial life – and if so, how – is addressed in the Talmud, one of the most important collections of Jewish writings since Antiquity. According to the Talmud, the righteous are theoretically capable of creating a world, but their creative abilities are limited by their sins.

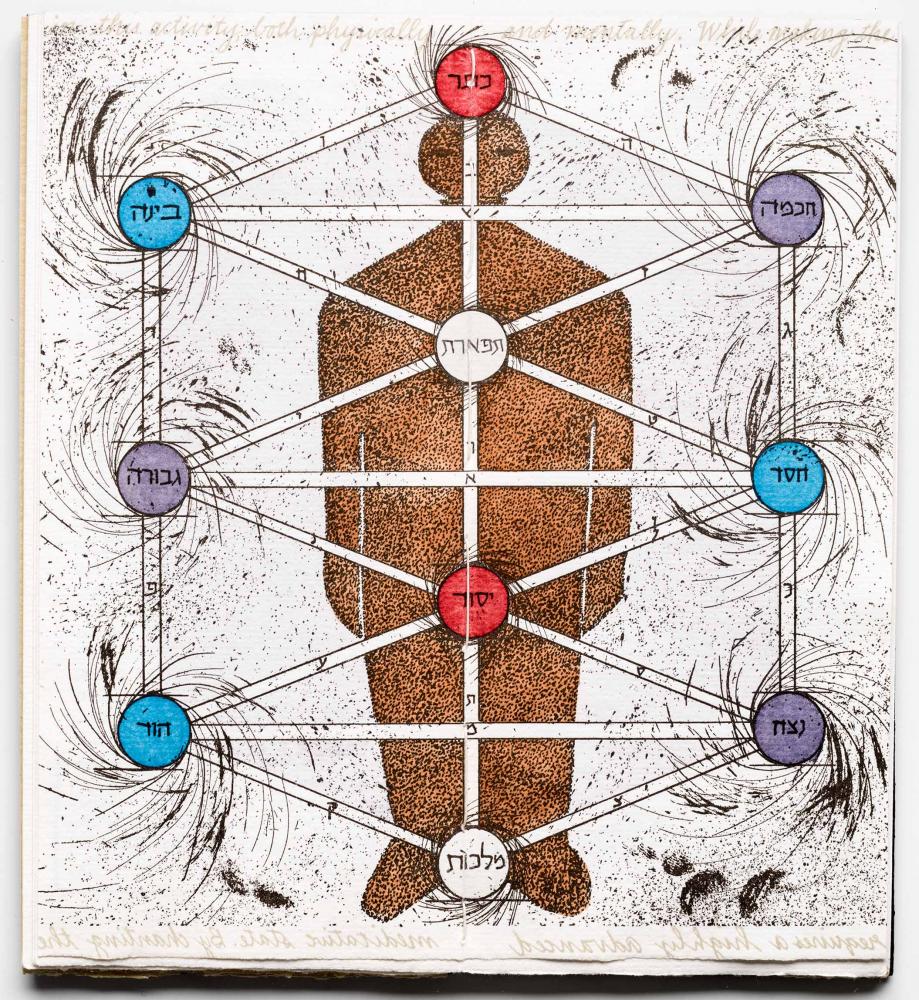

Nevertheless, pious Jewish mystics in southern Germany made their first concrete attempts to create a golem in the Middle Ages. In so doing, they sought to express their proximity to God and attain spiritual perfection. At the center of the act of creation were specific combinations of Hebrew letters, said to animate a golem formed of clay or dust. Unlike later golem legends, these Jewish mystics were predominantly focused on the process of creation. The procedure itself was more important that the purpose a golem might serve.

X

X

In the artist’s book Breathing Mud from 1999 by Lynne Avadenka, a golem emerges behind the ten sefirot – divine powers – out of which the earthly world is created; photo: Lynne Avadenka.

The Creative Power of the Alphabet

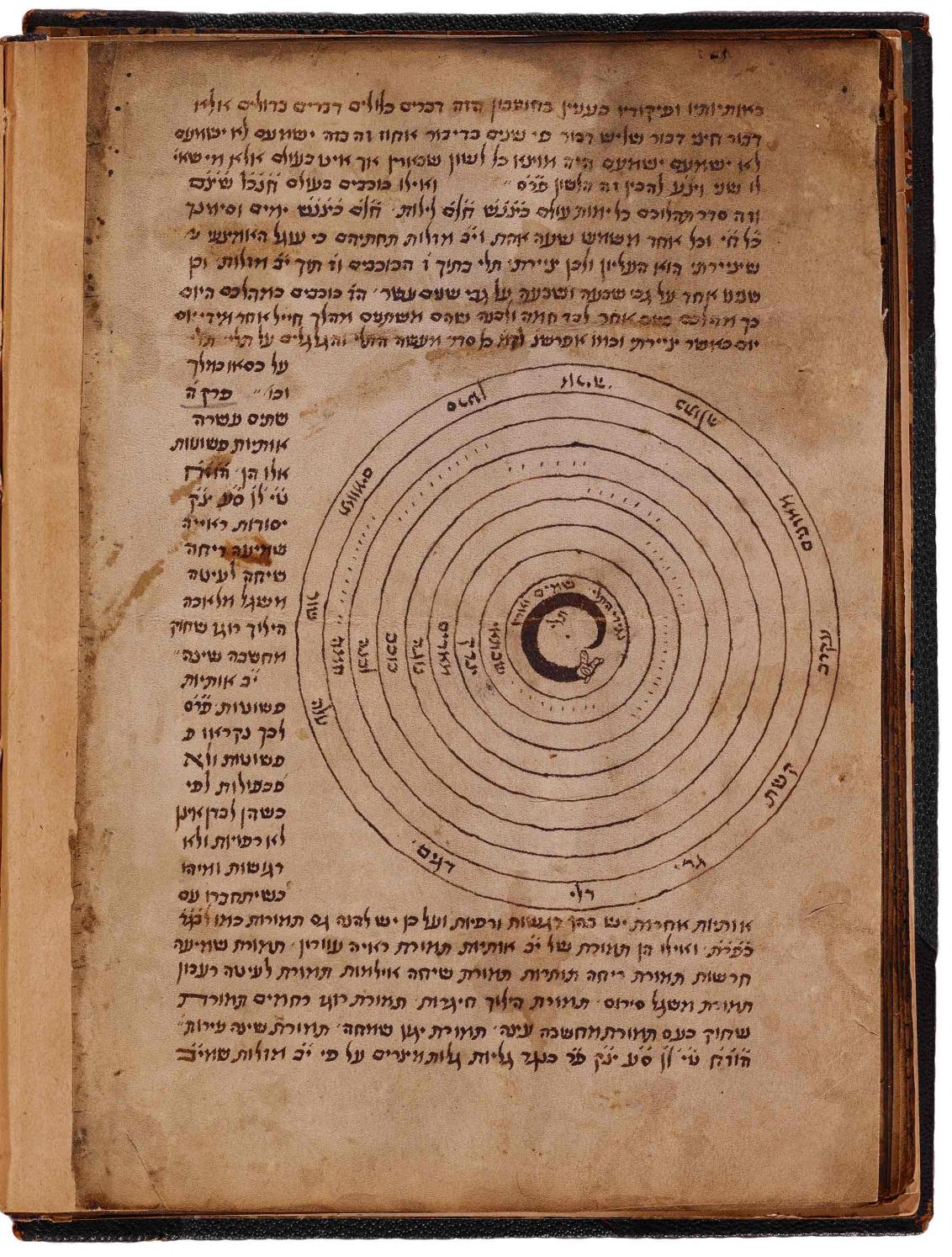

The first practical instructions on creating a golem can be found in medieval commentaries on Sefer Yetzirah (Book of Creation). In these "golem recipes," combinations of letters from the Hebrew alphabet with the letters of God's name play a central role. Sometimes the instructions are accompanied by cosmological diagrams, charts, or wheels of letters indicating the precise configurations of letters or celestial constellations required for the magical act of creation. When a person performs this act of incarnation, even small errors can have grave consequences, the recipes warn.

In this German-language video clip, Peter Schäfer, director of the Jewish Museum Berlin, explains the mystical significance of letters used to create a golem. The footage comes from the ARTE documentary Golem – Die Legende vom Menschen (Golem – The Legend of Man); rbb/Medea Film Factory 2016.

Commentary on Sefer Yetzirah (the pseudo-Saadia commentary), attributed to Saadia Gaon (882–942). This transcription is contained in a manuscript produced in fourteenth-century Spain that is currently in the collection of the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York; photo courtesy of the Library of the Jewish Theological Seminary, New York.

Artistic Interpretations Today

Many contemporary artworks address the creation of a golem through the power of letters of the alphabet. Joshua Abarbanel also touches on this topic in the golem sculpture he created for the GOLEM exhibition at the Jewish Museum Berlin. Abarbanel's golem is composed of Hebrew letters, referencing a specific method of creating a golem. In this case, the golem is brought to life with the word emet (אמת), or "truth," consisting of the three Hebrew letters aleph, mem, and tav. Without the letter aleph, the word met (מת), meaning "death," is formed, and the golem reverts to a lifeless clod. Abarbanel's golem is made of the letters mem (מ) and tav (ת), with the aleph (א) hanging loosely around its neck. This means the golem is in a transitional state: Has it just been rendered lifeless, or is it waiting to be brought to life?

In this video, American artist Joshua Abarbanel talks about his work on the outsized golem sculpture that he created for the golem exhibition at our museum. A photograph of the sculpture can be seen at the top of this page. The footage comes from the German-language ARTE documentary Golem – Die Legende vom Menschen (Golem – The Legend of Man); rbb/Medea Film Factory 2016.

Like medieval mystics, Rimma Gerlovina, Mark Berghash, and Valeriy Gerlovin collaborated to create this life-sized Golem II, combining elements of photography, pattern poetry, and body art; The Jewish Museum, New York, Gift of Elizabeth Cats.

Readings of Golem II

The Hebrew letters that were painted on Gerlovin’s and Gerlovina’s bodies and photographed by Berghash can be read in many different ways, resulting in a clever play on words and genders: Horizontally, the letters form the Hebrew words for truth (אמת) and death. Vertically, they form the Hebrew words for blood (דם), man (אדם), and madam (מאדם).

Mud Men

Other artworks that address the golem theme focus more heavily on the materials used to create them – earth, sand, clay, and dust – and the transformation from an inanimate substance to living flesh. This transformation is a key to the golem as a subject. For artists, the golem motif serves as a powerful metaphor for artistic creation and for the struggles to give form to material. Moreover, as soon as an artwork is completed, it escapes the control of the artist, just as a golem escapes the control of its creator.

X

X

In 1970, the artist Charles Simonds filmed and photographed his performance Birth, in which he reenacted a golem birth ritual in a clay pit in New Jersey. This color photograph is from the artist's private collection; photo: Charles Simonds.

Emergency Helper or Volatile Monster?

In all the traditional stories, the golem is an ambiguous figure. Usually, it is created as a servant, companion, or rescuer to help an entire Jewish community facing danger. As a powerful symbol of Jewish self-assertion, the golem has been stylized and longed for as a superhero in times of crisis.

The journalist Egon E. Kisch, persecuted as a Jew, rhetorically summoned the golem in 1938.

You know that I'm a direct descendant of the sage Rabbi Loew, who modeled the golem out of clay and commanded it to ‘arise and go!’ when the Jews were threatened with injustice. We could use a golem like that when the Nazis attack us. I too would give the command: 'Arise and go! Our enemies are closing in on my Prague!'

Once the golem's power is unleashed, it can no longer be controlled. The hero mutates into a monster, spreading fear and terror.

The golem thus became a fitting metaphor for many of the challenges confronting modern society in the twentieth century and the present day. In particular, the golem symbolizes destructive and uncontrollable developments that humanity has inflicted upon itself.

Fritz Ascher created his painting Golem in 1916, during the First World War, a crisis that has been called the great seminal catastrophe of the twentieth century. In his depiction, the golem rises above the crowd of figures like a grim Messiah. The painting belongs to the collection of the Jewish Museum Berlin; photo: Hermann Kiessling.

In the postwar period, the invention of the atomic bomb was compared to the creation of a golem.

The Vienna-born physicist Wolfgang Paul reasoned in a letter form 1954:

Physics has not only produced useful inventions, but also what is termed soulless technology ... Indeed, it gave birth to the atomic bomb ... Physics has thus been made into an 'autonomous phenomenon,' detached from the physicist and his soul, which is in fact what begets all of it. And so it becomes a sort of golem.

Interestingly, Pauli's choice of metaphors was not his only connection to the legend. His father was the Jewish publisher Wolf Pascheles, who had published Sippurim, a popular collection of Jewish stories, in 1853. The golem story in the book was central to the legend's spread and popularization until the turn of the twentieth century.

The Golem of Today

Today, specialists develop artificial creations that simulate consciousness, store memories, and express aggression or empathy. Machines and robots with complex algorithms perform a wide range of functions. By extension, they can be seen as modern golems, standing for the ambiguity of hope, skepticism, and danger in the face of the achievements of a world increasingly dominated by technology.

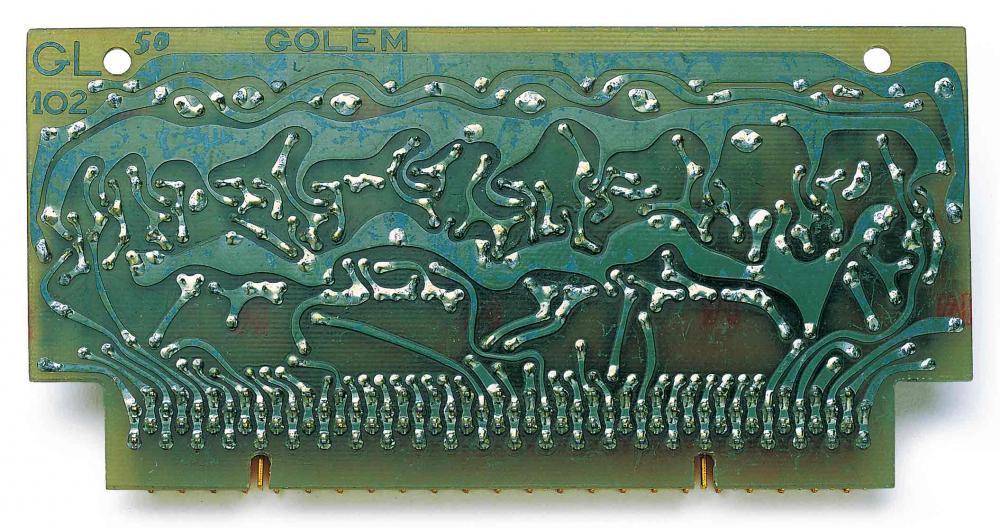

Gershom Sholem, a scholar and specialist in Jewish mysticism, discussed the analogy between the golem and artificial intelligence as early as 1965. He gave an Israeli mainframe computer the name "Golem Aleph," expressing his hope that the machine would remain peaceful.

X

X

This is the circuit board of Golem Aleph, produced in 1963 and currently in the possession of Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel; photo: Weizmann Institute of Science, Israel.

The Spanish company PAL Robotics designed these two humanoid robots, REEM and C, in 2013; photo: PAL Robotics.

The Golem and Gaming

Since the 1970s, countless successors of the golem have inhabited various role-playing games and computer games. These golems, which initially took analog form in games such as Dungeons and Dragons, later entered the digital worlds of Minecraft and Clash of Clans. In the world of collectible toys and figurines, there is a wide assortment of golem action figures.

Golem figures, 21st century; Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Stefanie Haupt

Whether in art, popular culture, political discourse, research laboratories, or the world of Minecraft, the golem – the concept of humans creating artificial life – is alive and well!

Citation recommendation:

Anna-Carolin Augustin (2016), Golem. From Mysticism to Minecraft.

URL: www.jmberlin.de/en/node/4164

X

X