“I wish more people would look in my eyes instead of at my scarf”

Questions to Fereshta Ludin

Julia Jürgens, Rafiqa Younes

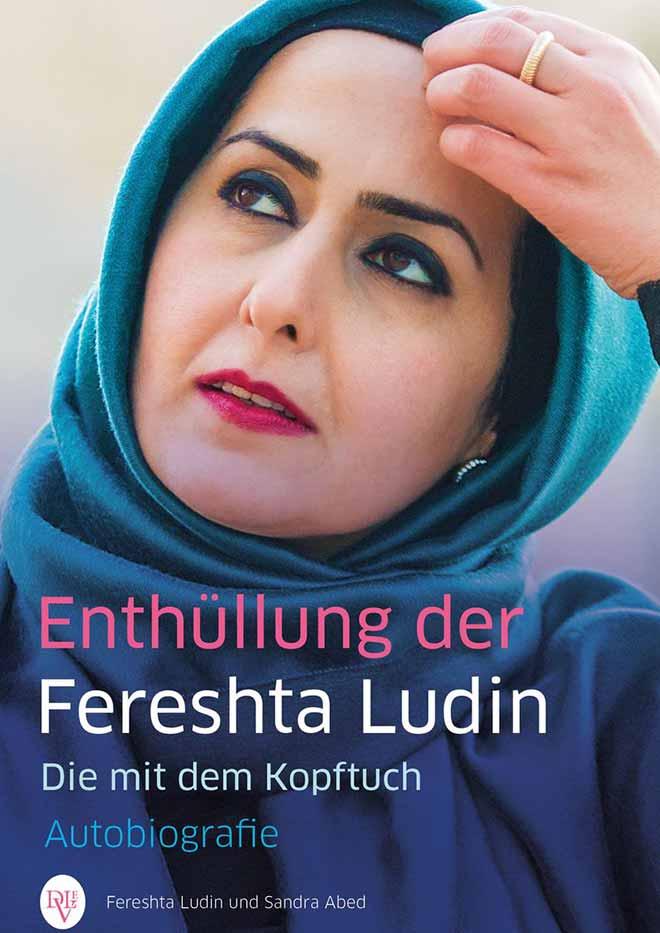

To win the right to work as a teacher in the classroom while wearing her headscarf, Fereshta Ludin had to go all the way to the German Supreme Court (see below Background Information: German Supreme Court Rulings on Headscarf Ban). On 17 September 2015, she joined us as part of the series New German Stories to introduce her book Enthüllung der Fereshta Ludin. Die mit dem Kopftuch (“The Unveiling of Fereshta Ludin: The One with the Headscarf”).

On 16 September 2015 Rafiqa Younes and Julia Jürgens did an interview with Fereshta Ludin and asked her the following questions:

Did you ever guess that the first lawsuit you filed against your employers, in 1998 when you were 25 years old, would set off a nationwide debate about the headscarf ban?

You can’t really imagine something like that. I was still very young and idealistic. I wanted to work as a teacher and had no intention of provoking the public or any politicians.

From your perspective, was it worth it to go all that way through courts, becoming, as you did, a public figure – “the one with the headscarf”

as the title of your book ironically references?

I don’t regret a single step along the way. I would have regretted much more, to have had to endure the injustice. I took an active stand against discrimination by going through the courts. Many other women were also affected. It was never my aim to become a public person. Germany’s public projected the subject ‘headscarf’ onto me and reduced many educated, competent women simply to their scarf. For years. I hope that it changes in the future. That would be my wish.

What was it like for you to experience the reactions to the debate: did you receive support from unexpected quarters? Or was there criticism that surprised you?

There was criticism constantly and from almost all sides, including the Muslim community. I was surprised when politicians had the courage to speak out on a positive note and, regardless of what they personally thought about headscarves, to stand up for the right of these women to work and not to be discriminated again. There were only a few like this for me to admire, however.

X

X

Book cover of Enthüllung der Fereshta Ludin. Die mit dem Kopftuch (“The Unveiling of Fereshta Ludin: The One with the Headscarf”); Deutscher Levante Verlag

What is your sense of the situation today in Germany for women who wear a headscarf? Would you say that the atmosphere in public has changed?

The atmosphere has changed politically. It’s not as closed and prejudiced, but there is still a lot to do in terms of anti-discrimination work. In my view it is crucial to stand up for and promote ethnic, cultural, and religious diversity more strongly. In the last 17 years, since the start of the public debate about the headscarf, Muslim women have had to fight long and hard against discrimination. Many people don’t realize this, so I think we should talk and reflect openly about it.

In your book you write that ever since you decided at the age of 12 to wear a headscarf, you have been confronted with the same questions: were you forced to wear it, isn’t the headscarf a symbol of oppression, etc.? What questions would you rather be asked?

I would rather not have constantly to explain the reasons and to justify my personal choice to wear the scarf. Every woman should decide how she dresses herself, including Muslims with the headscarf. It shouldn’t matter what religious convictions another person has when they are standing in front of you, man or woman. What’s important is what they say, how they behave. I wish more people would look in my eyes instead of at my scarf.

Background Information:

German Supreme Court Rulings on Headscarf Ban

After she successfully completed her training in 1998, teacher Fereshta Ludin was denied a job in the Baden-Württemberg school system because she refused to stop wearing her headscarf. She sued, pursuing the case through all the possible appeals. On 24 September 2003, the German Supreme Court sided with the plaintiff and concluded that “a ban on wearing the headscarf, for teachers in schools and in the classroom, does not have an adequate, specific, legal basis in the existing law of the State of Baden-Württemberg.”

At the same time, the court pointed the states towards a possible successful basis for such a ban. Eight German states subsequently passed laws prohibiting the wearing of religious garments or symbols in schools and to some extent in other areas of public service. In five states (Baden-Württemberg, Bavaria, Hessen, North Rhine-Westphalia, and Saarland) variously written exceptions for Western-Christian and Jewish items of clothing and signs were included in the laws.

In a new decision on 27 January 2015, the Supreme Court found a general headscarf ban for teachers at public schools unconstitutional.

Citation recommendation:

Julia Jürgens, Rafiqa Younes (2015), “I wish more people would look in my eyes instead of at my scarf”. Questions to Fereshta Ludin.

URL: www.jmberlin.de/en/node/6345

Interview Series: New German Stories (12)