Consuming Light

A Short History of Ritual Light Consumption

Michal Friedlander

My sister was due to visit me from Los Angeles. “Can I bring you anything?”

she offered. My reply was swift: “Nice Hanukkah candles, please.”

The Festival of Lights lay some ten months in the future, but my sister is used to my odd requests by now.

I live in Berlin, where Jewish ceremonial candles are over-priced and the selection is limited. I not only force family members to weigh down their suitcases with boxes of hand-dipped Hanukkah

tapers, but I also take the liberty of asking friends traveling from Israel to bring me Jewish memorial (Yahrzeit) lights. This long-standing practice of mine is outdated (and unfair) as I could probably replenish my ceremonial candle supply with an Internet order, but I am slow in adjusting to this feature of modern life. Anyway, candles solve the house gift dilemma for my guests, so it works out for everyone. Jewish ritual practice involves lighting a lot of candles.

From the creation of light in the first chapter of the Hebrew Bible, light and fire are motifs that have permeated Jewish writings from antiquity to the present. Every mention of light in the Hebrew scriptures has been pored over and studied—its context and meaning debated and interpreted. There is no single meaning for light in Judaism and over time, various light metaphors have been transformed into elements of ritual practice.

X

X

In Judaism there is the custom (Minhag) to light a candle on the anniversary of the death of a loved one. This candle is supposed to burn for 24 hours, so there are candle stands of special size to hold a candle with a long burning time.

Jewish Museum Berlin, Photo: Roman März

The most familiar candle lighting ceremony takes place shortly before the onset of the Sabbath, or other major festivals. Light is connected to creation and the moment of distinction between day and night, light and darkness, the sacred and the profane. The transition at the closing of the Sabbath is marked by a ceremony called Havdalah that also involves candle lighting.

The word Havdalah comes from the Hebrew verb lehavdil, to separate: The festival has come to a close and the creation of fire marks the return to secular time and the regular workday.

In Judaism, light rituals are integrated into other festival traditions, and rituals that mark life cycle events: circumcision, marriage and death. Customs vary according to region and time period. The high level of ceremonial light consumption leads to a significant question, which has confronted Jewish communities for generations: Where can we get candles?

X

X

Leonard Freed, Shabbat, Blessing the Candles. From the series German Jews today. Frankfurt / Main, 1961;

Jewish Museum Berlin

This issue goes all the way back to biblical times. Following the giving of the Torah at Mount Sinai, God gives instructions to build a tabernacle (mishkan), a dwelling place for God on earth. Among the detailed building instructions is a command for the Israelites to bring clear oil, made from beaten olives, to feed the light of the lampstand in the portable tabernacle (Exodus 27:20). The lamp was to burn from evening until morning, dispelling darkness. Rabbis later estimated that between 6 and 10.6 fluid ounces would have been needed on a daily basis. As the Israelites were required to prepare the finest olive oil, they shared the responsibility of making and maintaining light in the Tabernacle.

Leaping forward a number of epochs, the Jewish people were dispersed and came to settle in different parts of the world. When a Jewish community established itself, a place of learning and prayer was designated and when funds permitted, a synagogue was built, which was the gathering place and heart of the community. Just as the ancient Israelites shared the responsibility of maintaining the lamp flames in the mishkan, members of a synagogue organized themselves to ensure that the ner tamid, the perpetual lamp in the synagogue, had sufficient oil for the flame to be maintained. Prior to electricity, the community members also made sure that the synagogue had sufficient candles or oil for general lighting purposes. The maintenance of the ner tamid remains of supreme importance today. While many synagogues, for reasons of safety, now use an electrified lamp, in Central and Eastern Europe of the thirteenth to fifteenth centuries (Ashkenaz) it was not uncommon to form a special society, a Chevrat Ner Tamid to raise the funds for the oil necessary to keep this flame alight.

Aside from donations and fund-raising to maintain synagogue light, a rather ingenious idea was introduced in many congregations: a so-called “wax penalty” (Wachsstrafe) that was also employed in the church. In Ashkenaz, many examples can be found of synagogue statutes that stipulate penalties to be paid in wax, which was collected for the synagogue, the school, or for the poor. Such penalties were applied in cases where a member broke the synagogue rules. Bad behavior during prayer services appears to have been a particular problem: arriving late, making excessive noise, talking about inappropriate subjects, or fighting during services, were commonly fined with between one to three pounds of wax. (The Wachsstrafe was originally paid in kind. It became a monetary fine during the nineteenth century, but kept its name.)

What is Ashkenaz?

Ashkenaz, Hebrew, used since the Middle Ages to describe the area of present-day Germany, later also a description of (northern) France and northern Italy.

The “wax penalty” benefited Jewish communities in the form of wax that could be distributed for charitable and ritual use. However, the fat that many light rituals are intrinsic to Jewish practice was exploited in a politically motivated penalty, intended to undermine the financial stability of Jewish communities. In September 1810, Franz I, the self-proclaimed Emperor of Austria, issued an edict targeting the Jewish population of Galicia. It detailed a “light tax” (Lichterzündungs-Aufschlag) to be put on every single candle or lamp that was lit for a Jewish ritual purpose. The edict itemized Jewish uses of ritual light, with considerable knowledge about the number of lights kindled on each occasion. Extra taxes were also applied to kosher meat, but a person could limit his or her meat intake. As Jews were religiously obliged to use light for certain ceremonies, the only way to lower the tax penalty was to use tallow candles or oil where possible, rather than beeswax, as these two light sources were taxed at a lower rate.

Beeswax has always been an expensive luxury commodity and Jews often had to make do with tallow candles. Tallow is a non-kosher product made from animal fat. This could give rise to a problem mentioned in the childhood memoirs of a popular Yiddish author, who wrote under the pseudonym Sholem Aleichem (1859–1916). During the community celebrations of Simchat Torah, the children of his home shtetl Voronko paraded with homemade paper flags attached to sticks. The top of each stick was inserted into an apple, which in turn was crowned with a flaming candle.

"Now all I needed was an apple and a candle. A candle made of wax, of course, and not tallow—for if tallow dripped on the apple, the apple was ruined and couldn’t be eaten. But wax didn’t matter—wax was kosher. When it came to wax, I had more of it than any other kid. [...] For after all, my father was the assistant sexton of the basement prayer-room annex of the Butchers’ Synagogue. Whatever was left of the candles after Yom Kippur belonged to him—that was his to keep."

Sholem’s father would melt down the remnants of the Yom Kippur candles and make Hanukkah and Havdalah candles. Sholem was allowed to collect the remnants of the melted Havdalah candles, which he in turn reused for Simchat Torah. The text alludes to a particular light ritual on Yom Kippur that was followed for centuries in central and Eastern European Jewish communities. In addition to the festival lights lit on the eve of Yom Kippur, two much bigger candles—large enough to remain alight throughout the holiday—were kindled. One candle was the ner ha-briah, the “light of health”, lit by every married man or widow. The other was the ner neshama the “light of the soul”, a memorial light that is (still) kindled by each man or woman with a deceased parent.

X

X

This work by Alexis Hyman Wolff deals with the search for one's own roots - the artist shaped the found objects from California and filled the roots with beeswax.

Alexis Hyman Wolff, root candles, hand cast, Berlin 2013.

Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Jens Ziehe

In general, the “light of health” was brought to the synagogue on the eve of Yom Kippur. It was considered a bad omen if the flame went out and the candles were often grouped together so that it would be difficult to keep track of one’s own candle. The candle stumps were left behind in the synagogue, further severing any personal connection, and the remaining wax was gathered and reused for other ritual purposes.

These large Yom Kippur candles were made by the women in the communities and as they prepared the wicks (kneytlach leygn), they said special prayers, known as tkhines. Most notable is an eighteenth century petitionary prayer written by Sara bat Tovim, specifically for this ritual. It includes the words: “May it be Your will that on this Yom Kippur eve, we be remembered for good as we donate these candles to the synagogue [...] May our prayers by the light of the candles be said with complete intention and faith…”

The mechanization of candle production ended the long tradition of women preparing ritual candles, but Judaism is a living religion and new rituals arise naturally. The unspeakable human loss of the Shoah led to feelings of devastation and grief in the wider, Jewish community. As part of the mourning process, it became evident that there was a particular need to come together, to remember those who had died and to mourn and pray. Yom HaShoah, Holocaust Remembrance Day, has been observed in Israel since 1949 and was adopted by Jewish communities around the world. Although Yom HaShoah has been observed for over sixty years, there is still no official liturgy or ritual attached to its observance.

In Yom HaShoah memorial ceremonies it is common practice to light six candles, representing six million murdered Jews. The symbolic sevenbranched menorah is often used for this purpose: the seventh branch implemented as a servitor light. Holocaust survivors often kindle these lights, but this custom will not be tenable for much longer, as the generation of survivors is dying out. Jewish light rituals have led to the production of Sabbath candlesticks, Hanukkah and ner tamid lamps, as well as memorial lights, but does this new ritual practice require a designated Yom HaShoah candelabrum or some other kind of ritual-specific memorial light?

X

X

Helmut Lueckenhausen, Candleholder for Yom HaShoah, 150 cm, Queensland Blackwood verneer over hardwood and aluminum, Australia, 2008-9; Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Jens Ziehe

In the 1970s, members of the Federation of Jewish Men’s Clubs in the United States originated the idea of a symbolic yellow candle for Yom HaShoah. The Yellow Candle™ Program has become a successful and far-reaching program: over 200,000 Yellow Candles™ are distributed each year.

Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Roman März

Many Jewish light rituals are a religious obligation, but lighting Hanukkah candles is a ritual that is also popular among non-orthodox and secular Jews. Such rituals become integrated into a personal calendar and way of life, to be performed wherever one may find oneself. Miniature Sabbath light travel sets and immigrant packing lists show that light rituals are an issue for Jews on the go. The Faifer family of Berlin fled Nazi persecution in 1938. Among their belongings they packed a Hanukkah lamp and several boxes of Hanukkah candles. Just in case. The Faifers reached Australia and must have found ample candles, because the Berlin candle stockpile was kept in a cupboard for nearly eighty years and was never depleted.

X

X

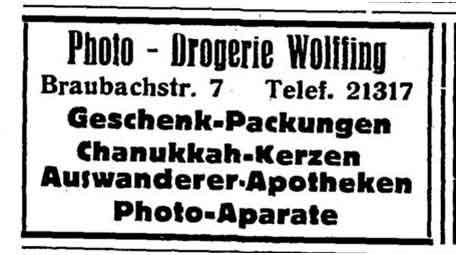

This drugstore advertisement from a Frankfurt Jewish community newspaper reflects the needs of émigrés in December, 1937. It lists: gift wrap, “travel first aid kits for émigrés,” cameras and, of course, Hanukkah candles.

Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Roman März

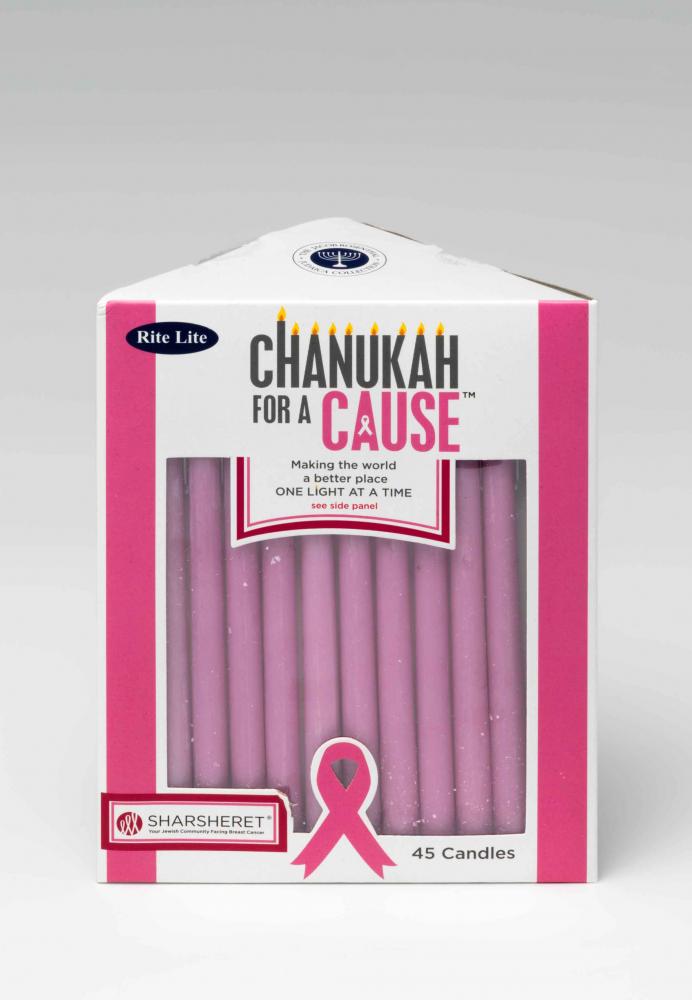

Unpacking the candle hoard that my sister brought me from Los Angeles, I discover an assortment that is foreign to Germany. She has included a pink set of candles that are sold to raise money for a Jewish breast cancer organization, and a set in shades of khaki, which are sold in support of U.S. troops. I wonder if the political agendas and cultural preoccupations of the present will be evident in Jewish candle rituals of the future? Will Holocaust Remembrance Day still exist in 150 years and if so, will there be a special form of candlestick for the memorial ritual? What is certain is that for as long as Judaism is practiced, there will always be a need for ceremonial light rituals.

And for a source of light.

Michal Friedlander has worked at museums in New York, Los Angeles, and Berkeley. She has curated numerous exhibitions and published on a wide range of Jewish topics. Since 2001 she is the curator for Judaica and Applied Arts at the Jewish Museum Berlin.

This article was first published in 2018 in issue 18 of the print edition of the JMB Journal.

X

X

Rite Lite Hanukkah candles sold to support women and their families who are facing breast and ovarian cancer.

Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Roman März

Citation recommendation:

Michal Friedlander (2018), Consuming Light. A Short History of Ritual Light Consumption.

URL: www.jmberlin.de/en/node/5536