Life and Work of Curt Bloch

Some eight decades since these lines were written, and nearly fifty years after his death, Curt Bloch’s hopes are now finally being fulfilled. Over a period of more than nine teen months between August 1943 and April 1945, he produced a unique work of creative resistance while in hiding in the Dutch towns of Enschede and Borne: Het Onderwater-Cabaret. Week by week, Bloch put together small-format booklets comprising handwritten poems, in both Dutch and German, that confronted Nazi propaganda and addressed a wide variety of themes: the course of the war, the lies and crimes of the National Socialists and their collaborators, his own situation in hiding and the fate of his family, the approaching collapse and defeat of the Axis forces, and the future of the German people. Through caustic satire and sardonic wit, Bloch mocked and ridiculed all the major fascist leaders—from Hitler, Goebbels, and Göring to Mussolini and Arthur Seyss-Inquart, Reich Commissioner of the Netherlands—alongside a host of their subordinates and henchmen, while always remaining acutely conscious of the enormity of their atrocities.

"Perhaps at some point in the future,

the poems in your tongue I composed,

will be brought to your notice, and if so,

to delight will I then be disposed."

(Excerpt from: “To my German Readers,” 3 June 1944)

Life Before Hiding

Curt Bloch was born in Dortmund in 1908 to Paula and Siegfried Bloch. His sisters Erna and Helene followed in 1912 and 1923. His father had a delicatessen on Reinoldistrasse in the center of Dortmund that also sold kosher foodstuffs. After graduating from high school, Bloch studied law in Bonn, Freiburg, and Berlin and earned his doctorate at the University of Erlangen. This was followed by legal clerkships in Lünen, Cologne, and Dortmund. In April 1933, the Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service ruled out a future for Bloch as a lawyer in Germany. In addition, the politically leftist Bloch was personally threatened, whereupon he fled to the Netherlands, settling first in Amsterdam. After engaging in various activities, among them writing for a German-language exile newspaper—Bloch had previously penned articles for the Dortmunder General-Anzeiger—he was employed in 1935 as a salesman at the Persian carpet dealer E. Perez in The Hague. There he was joined by his mother Paula and younger sister Helene in the spring of 1939, after antisemitic smears and the forced closure of the family business led them to flee Germany.

On May 10, 1940, the Germans invaded and occupied the Netherlands. Only four months later, the Blochs had to leave The Hague after non-Dutch Jews were forbidden to live in towns along the coast. The family moved to the eastern city of Enschede on the German border, where Bloch continued to work for E. Perez at their branch in the city until October 1941. Thereafter he was able to sell carpets and other art works independently and thus provide for his mother and youngest sister. In December 1941, his sister Erna and Max Levy, whom she had married in 1935, were deported from Düsseldorf to Riga.

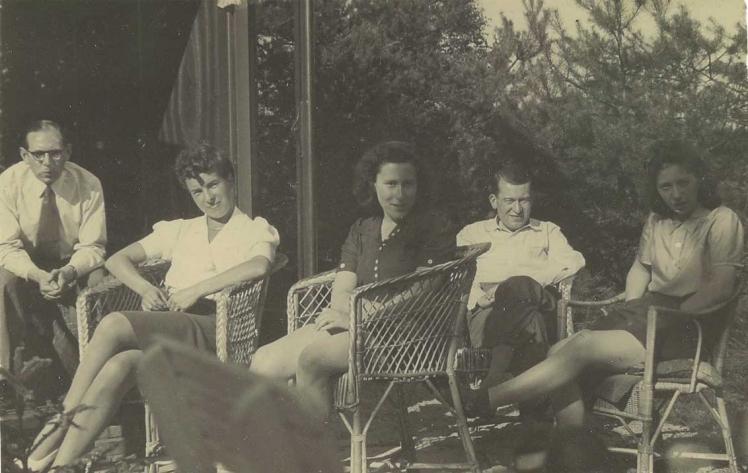

From left: Bruno Löwenberg, an unknown woman, Helene Bloch, Curt Bloch and Karola Wolf, presumably taken in the summer of 1941; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession.: TE83 (OndCab)/29, gift of Robert Saunders

Creative Resistance

Curt Bloch went into hiding in Enschede on August 25, 1942, some six weeks after the first mass deportation of Jews from the transit camp of Westerbork to Auschwitz. He was aided by a resistance group formed by the Enschede pastor Leendert Overduin to save Jews from the city and other towns throughout the province of Overijssel. His mother and sister first found refuge in Apeldoorn and later in Leiden. Bloch was taken in by Albertus Menneken and his wife Aleida in their house at Plataanstraat 15. In the fall of 1942, he was joined there by Karola Wolf and Bruno Löwenberg, whom

he had met following his arrival in Enschede two years earlier. The three of them were lodged in the attic, but able to spend time in other rooms of the house at different times of the day.

Curt had begun writing poems in the spring of 1943 and possibly even earlier, referring to them collectively as Tijdsgedichten (Poems of the Times). It is high likely that a major impetus was the airing on German-controlled Dutch radio of a propaganda program entitled Zondagmiddagcabaret (Sunday Afternoon Cabaret). This was the brainchild of the Dutch lyricist Jacques van Tol, who created it to counter a cabaret program broadcast by Radio Oranje, the voice of the Dutch government in exile in London. As the Radio Oranje revue parodied both the German occupiers and their Dutch collaborators, it too may have given Bloch inspiration for his Onderwater-Cabaret. (OWC) Bloch almost certainly presented his verses to the Mennekens, Karola Wolf, and Bruno Löwenberg in his own “Sunday Afternoon Cabaret,” as testified by a collection of poems he put together in early July 1943 for Karola under the heading Instead of a Zondagmiddagcabaret.1

The relationship between Curt Bloch, Bruno Löwenberg, and Karola Wolf was a challenging one. Karola came from Krefeld and had been able to go to England in the spring of 1939, but joined her parents in Enschede after they moved there in July 1939. Bruno Löwenberg came to the city in 1933 from Aachen, and made a living there as a successful textile merchant. He and Karola Wolf were a couple when they moved in to the Mennekens’ home, but Curt, who had arranged for them to come there, became increasingly fond of Karola. After receiving news of the arrest of Paula and Helene Bloch along with Bruno Löwenberg’s father Berthold and his sister Elise in a boarding house in Leiden on May 5, 1943, all three left the Menneken house —Karola permanently, Curt and Bruno only temporarily. Some three months later, Curt began writing to Karola, and it was in this connection that he created Het Onderwater-Cabaret.

Het Onderwater-Cabaret and Secret Service

The title Het Onderwater-Cabaret appears first in a booklet written for and sent to Karola on the occasion of her twenty-third birthday on August 14, 1943: Coba’s Verjaardags-Cabaret (Coba’s Birthday Cabaret), a festive presentation of the Onderwater-Cabaret. On the following day, August 15, Bloch produced “A Special edition of the ‘Onder Water Cabaret’ instead of a long letter,” with the title Secret Service. Just one week later, the first issue of Het Onderwater-Cabaret proper “appeared.”

For the next seven months, Bloch worked simultaneously on Het Onderwater-Cabaret and Secret Service, each produced once a week. Both had the same format (13,5 x 10,5 cm) and the covers of both were adorned with photomontages and collages that Bloch made using materials from newspapers and magazines available to him. Secret Service comprised almost exclusively love poems, written mostly in German and very often in an endearingly amusing style, whereas the verses of Het Onderwater-Cabaret were primarily political satire and in the first four months were composed mainly in Dutch. While the satirical poems were known to and shared with the Mennekens, Bruno Löwenberg, and other friends and visitors to the house, the love poems remained eponymously secret, and Curt went to great lengths to keep them so. Both “periodicals,” as Bloch referred to them later, were sent in sealed letters via different messengers to Karola, the only recipient of Secret Service and the primary reader of Het Onderwater-Cabaret. In a letter written in October 1943, Bloch explained the purpose of the latter series:

“If you contribute to making the German evil spirit ridiculous—ridicule kills!—then you not only help the German people, but at the same time work in the interest of Europe and the world.”

In the same letter, he expressed the hope that

“through my poems I might play an educational role, especially in the spiritual and intellectual construction of a new Germany.”

X

X

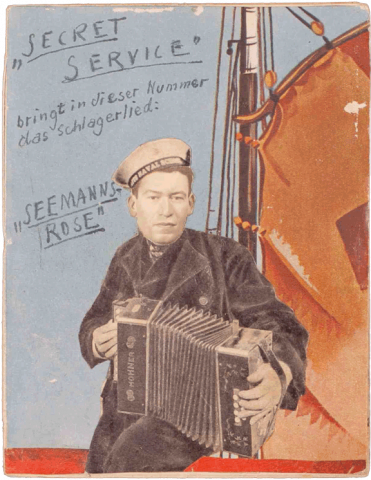

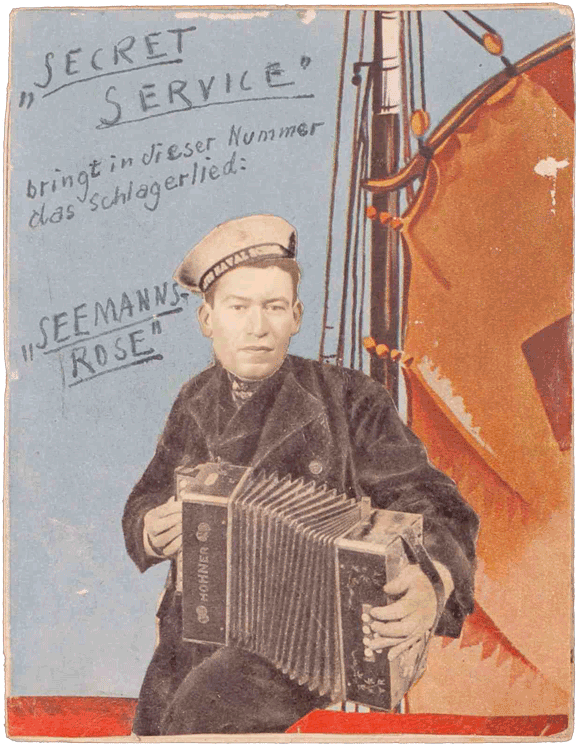

Secret Service No. 27 "Seemannsrose", February 1944; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession.: 2023/141/26, gift of Robert Saunders

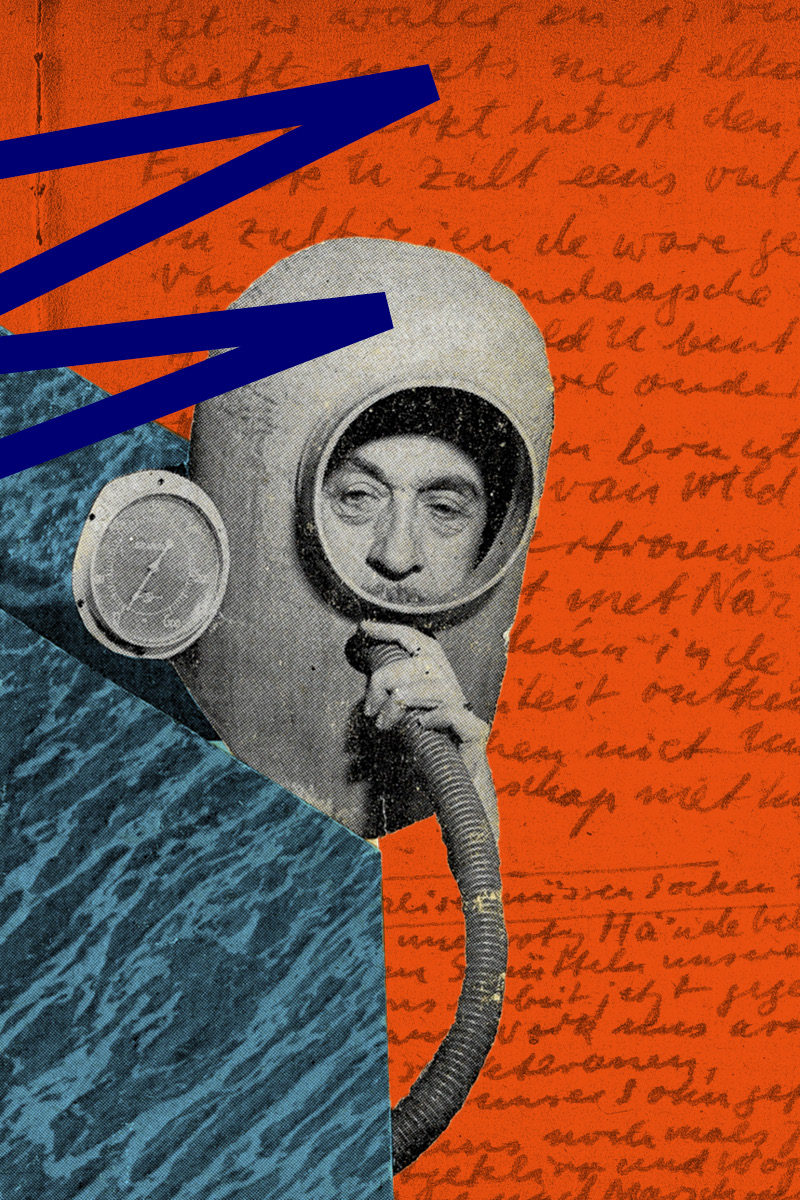

Cover pages Het Onderwater-Cabaret

Curt Bloch, Het Onderwater Cabaret, Magazine cover from 30.08.1943, Jewish Museum Berlin, Curt Bloch collection, loan from the Charities Aid Foundation America

Curt Bloch, Het Onderwater Cabaret, Magazine cover from 18.12.1943, Jewish Museum Berlin, Curt Bloch collection, loan from the Charities Aid Foundation America

Curt Bloch, Het Onderwater Cabaret, Magazine cover from 16.09.1944, Jewish Museum Berlin, Curt Bloch collection, loan from the Charities Aid Foundation America

Cornelis Breedenbeek in Hiding

Curt Bloch’s literary production was not limited to Het Onderwater-Cabaret and Secret Service. In September 1943, he completed Het boek van Piet en Coba (The Book of Piet and Coba) “for young people aged eight to eighty”, which presented twelve adventures of two youngsters engaged in acts of resistance against the German occupiers of the Netherlands. A lengthy autobiographical work entitled Dortmunder Bierzeitung about his hometown and his life there, especially about his teachers and fellow pupils at the high school, was written between September 1943 and February 1944. In May 1944, he finished the satirical work Irrfahrt durch den Weltenraum (Odyssey through Space), which recounted the ethereal wanderings of the ghosts of Hitler and Mussolini in search of a final resting place. All of these works, penned under the pseudonym of Cornelis Breedenbeek, were written in rhymed verse, and all were sent to Karola Wolf for her perusal and review. Bloch was also busy writing cabarets and congratulatory pieces for the birthdays and anniversaries of friends and helpers. Additionally, he was working on a longer piece of prose entitled Op wilde vaart (At Breakneck Speed) of which, however, nothing has survived.

Curt Bloch’s intensely imaginative and engaging love poems, combined with his other writings and lengthy letters, achieved the desired effect. Nonetheless, his relationship with Karola Wolf, whom he credited with giving him inspiration and motivation, remained “making love per distance,” as Bloch described it, despite the fact that they were able to meet briefly from time to time. Due to the “inadequacy of correspondence,” the circumstances of the time, and the anxiety and depression that inevitably accompanied life in hiding, the romance came to an end in March 1944. Bloch discontinued the Secret Service but kept writing regularly to Karola Wolf and sent her most issues of Het Onderwater-Cabaret throughout his time in hiding, during which he continually expressed the hope that liberation might bring them closer together again.

Last Months in Hiding

In December 1944, Bloch left Enschede. He had long wanted to depart from Plataanstraat 15, his relationship with Aleida Menneken in particular having been tense almost from the start. He was taken in by Jeronimo and Johanna Hulshoff in Borne. The couple lived with their three children in a house on Wensinkweg 13, which had served as a short-term refuge for other Jews as well as for Dutch non-Jews who had gone underground to avoid forced labor in Germany. Bloch stayed with the Hulshoffs for three weeks. Their oldest child’s enthusiasm for Het boek van Piet en Coba led him to write three further adventures about the young resistance fighters. With the help of the Hulshoffs and others, Bloch was able to remain in Borne and continued to produce Het Onderwater-Cabaret. In a letter of January 10, 1945, he told Karola Wolf that some of his poems had been published. Three months later, on April 3, 1945, Borne was liberated by the British Royal Dragoons and the Nottingham Sherwood Rangers. Bloch’s last issue of the Cabaret bears that date and is entitled Bovenwater Finale van het OWC—Above-Water Finale of the OWC.

After Liberation

The freedom that Curt Bloch had so longed for was unfortunately not immediately accompanied by happiness. Shortly after the end of the war, he received the devastating confirmation that his mother and sisters had not survived. Paula and Helene Bloch, together with Berthold and Elise Löwenberg, were deported from Westerbork to Sobibor and murdered upon arrival there on May 21, 1943. Curt’s sister Erna Levy perished in Stutthof in fall 1944. A rekindling of the romance with Karola Wolf did not materialize.

Regrettably, Bloch apparently did not pursue any further literary ambitions. Although he had apparentely given some well-received readings of his poems in the weeks after liberation, his hope that his writings might be used for reeducation in Germany was not realized, something he attributed to his not having had the necessary connections. Added to this was the fact that he was obligated to provide proof of his antifascist sentiments, as testified by several letters of support written by Dutch citizens, among them Pastor Leendert Overduin— a situation that must have been particularly demoralizing for someone like Bloch who had so fiercely written against the Nazi murderers and their accomplices.

After remaining for some months in Borne and Enschede, Bloch moved to Amsterdam in the first few weeks of 1946 and worked for a time in a law office. In the spring of that year, he met Ruth Kan, who like him was born in Dortmund, in 1925, and whom had known his sister Helene. The couple married in July. Ruth had moved to Amsterdam with her parents and brother in 1939, her father being Dutch, but she too was the only one of her family to survive. Benjamin and Bertha Kan were murdered in Sobibor in May 1943, and Heinz Kan a year later in Auschwitz. Ruth herself had been brought in June 1943 to the Vught concentration camp in Noord-Brabant, where she carried out forced labor for the Philips company. She was deported to Auschwitz a year later, but after one week was taken to a camp in Reichenbach, south of today’s Wrocław. She later survived various camps, marches, and transports and was liberated in Denmark at the beginning of May 1945.

The Blochs’ first child, Stephen, was born in May 1947. One year later, in April 1948, the family emigrated to the United States and settled in New York, where their daughter Simone was born in 1959. Curt Bloch held various jobs until the late 1950s, when he established his own antique store called Continental Antiques Corporation. He died at the age of sixty-six on February 14, 1975. Before leaving the Netherlands, Curt Bloch had the ninety-five issues of Het Onderwater-Cabaret bound in four volumes, and his other writings in a fifth. In January 2023, all five volumes came to the Jewish Museum Berlin, where all the individual issues and works were carefully separated and restored in preparation for display. Through the exhibition, publications, and the presentation of the entire OWC online, Bloch’s verses, known to only a small number of people at the time of their composition, will now find the recognition and appreciation they so greatly deserve. And in today’s world, in which war, disinformation, discrimination, exclusion, and persecution are widespread, they remain highly pertinent.

We extend our sincere thanks to Simone Bloch for her trust in the Jewish Museum Berlin and for the close cooperation; to Robert Saunders, son of Karola Saunders née Wolf, for his donation of the thirty-six surviving issues of Secret Service and other writings and letters of Curt Bloch to his mother, as well as further correspondence and photographs; to Tamara Goldstoff-Loewenberg and Marcel Loewenberg for materials pertaining to their father Bruno Löwenberg, and to Lide Schattenkerk née Hulshoff, for her donation of items made by Curt Bloch for her family. Last not least, many thanks to Gerard Groeneveld for the helpful information he provided.

Since 2001, Aubrey Pomerance has been Head of Archives at the Jewish Museum Berlin and of branches of the archives of Leo Baeck Institute New York and of the Wiener Holocaust Library at the museum. Together with Ulrike Kuschel, he is the curator of the exhibition "My Verses are Like Dynamite” Curt Bloch's Het Onderwater-Cabaret.

This article was first published in 2024 in issue 26 of the print edition of the JMB Journal.

X

X

Title page, Het OWC of April 3, 1945; Jewish Museum Berlin, Konvolut/816, Curt Bloch Collection, on loan from the Charities Aid Foundation America thanks to the generous support of Curt Bloch's family

Citation recommendation:

Aubrey Pomerance (2024), Life and Work of Curt Bloch.

URL: www.jmberlin.de/en/node/10284

- The multilingual Curt Bloch wrote his letters and poems to Karola Wolf in four languages, German, English, Dutch and French—sometimes switching within a single sentence. He wrote the OWC in Dutch and German, though the last issue from April 3, 1945, includes a poem in English.↩︎

Exhibition “My Verses are Like Dynamite” Curt Bloch’s Het Onderwater Cabaret: Features & Programs

- Exhibition Webpage

- “My Verses are Like Dynamite” Curt Bloch’s Het Onderwater Cabaret: 9 Feb to 23 Jun 2024

- Accompanying Events

- Tour of the Exhibition “My Verses are Like Dynamite” Curt Bloch’s Het Onderwater Cabaret: Dates by arrangement (from 9 Feb to 26 May 2024)

- Exhibition Opening: 8 Feb 2024

- Curator Tour for FRIENDS OF THE JMB: 8 Apr 2024, in German

- Joodse Vluchtelingen: The Fate of German-Jewish Émigrés in the Netherlands: 3 Mar 2024, in German

- Archival Objects of German Jews in the Netherlands: Show & tell for FRIENDS OF THE JMB, 7 Mar 2024, in German

- Het Onderwater Cabaret Live. An evening of music and poetry: 11 Apr 2024, in German

- Publications

- JMB Journal 26: Het Onderwater Cabaret: Special edition on the occasion of the exhibition

- Digital Content

- OWC Online Feature: A Glimpse Behind the Scenes of the Exhibition

- Current page: Life and Work of Curt Bloch: Essay with biographical insights, JMB Journal 26

- Hidden in Enschede: Conversation with Contemporary Witness Herbert Zwartz: – Video recording, 16 April 2024, Jewish Museum Berlin, in German

- On the Piano of My Fantasy – Video with Marina Frenk, Richard Gonlag, and Mathias Schäfer, in German, Dutch and German Sign Language

- “It’s Complicated”: A text by Simone Bloch, daughter of Curt Bloch

- “Ik neurie mee ’t propellerlied…”: Essay on Het Onderwater-Cabaret: A Testament to Political Resistance in the Occupied Netherlands, 1943–45

- Clandestine Literature in the Netherlands 1940–1945: Essay, JMB Journal 26

- All Audio Pieces of the Exhibition with Transcriptions and Translations

- All issues of Het Onderwarter-Cabaret: All 95 issues to browse

- See also

- Survivors in Hiding (National Socialism)

- To the Web Project www.curt-bloch.com

X

X