Zvi Sofer

A Collector and His Collection

Three interests shaped the eventful life of the collector Zvi Sofer (1911–1980): music, folktales, and discovering and collecting Jewish artistic and cultural objects. That final interest resulted in a collection of more than 300 items of Judaica along with paintings, drawings, and everyday objects. In 1981, this collection was acquired for the Jewish Department of the Berlin Museum, a milestone along the way to the later establishment of the Jewish Museum in Berlin.

Who was the man who originally assembled this collection? What were his motivations? What can we learn about the objects and the origins of the Jewish Museum Berlin’s collection by revisiting his life story?

Zvi Sofer holding a large Hanukkah menorah from his collection. Photo location uncertain, taken in Lübeck, Duisburg, or Hanover in 1975; bequest of Zvi Sofer, Münster, photographer unknown

From Galicia to Palestine

Zvi Sofer, also known by the first names Zwi (in German), Gersh (in Yiddish), or Grisha (in Russian), was born on 28 January 1911 in the small town of Jałtuszków – now Yaltushkiv, Ukraine. The region had been part of the Russian Empire since 1793 and was incorporated as the Podolia Governorate.

Sofer was raised by an Orthodox Jewish family of modest means. His father died when he was six in the year of the Russian Revolution. His mother had to cover the family’s living expenses and left her son in the care of his grandmother and aunt.

Sofer attended cheder, Jewish religious school, where, as he later recalled, he began studying the Pentateuch at age five, Rashi’s commentary at seven, and the Talmud at eight. From age ten until his final examination from a humanistic-type Gymnasium (high school) in 1929, he attended secondary school in Brody, Galicia.

X

X

A young Zvi Sofer, probably surrounded by relatives; bequest of Zvi Sofer, Münster, photographer unknown

Zvi Sofer was musical. He learned to play violin at a young age, and music would be part of his career throughout his life. After graduating from school, he joined the Fourth Aliyah (1924–39) – partly because of his family’s difficult financial circumstances – and lived in Palestine for six years. There, he worked to help develop the country. The young Sofer was involved in brickworks and various workshops. In the early 1930s, he also gave solo concerts and directed multiple orchestras for children and young people.

Zvi Sofer working at a brickworks in Palestine; bequest of Zvi Sofer, Münster, photographer unknown

Studies in Vienna

In 1935, Zvi Sofer left Palestine and relocated to Vienna, where, starting in 1936, he studied art history, education, musicology, viola performance, and conducting at the Vienna Pedagogical Institute, the Vienna Conservatory, and the University of Vienna, according to his enrollment records.

Throughout Sofer’s life, he had positive associations with Vienna as the center of the multi-ethnic Austro-Hungarian double monarchy and as a place of Eastern European Yiddish and Chassidic culture. During his studies, Sofer took an early interest in contemporary efforts to write Russian-Jewish history and “work on national memory”

in keeping with the ideas of the Russian-Jewish historian Simon Dubnow. This is revealing in light of Sofer’s future interests as a collector.

Interlude: Simon Dubnow’s Call to “Join the Camp of the Builders of History”

In 1891, the historian Simon Dubnow called upon all Russian Jews to actively work on behalf of their people’s collective memory. This inspired an approach to Jewish history that placed a particular focus on the common people and on preserving Jewish folklore. Every Russian Jew, he believed, should become an amateur collector and play a part in writing this new history:

“I appeal to all educated readers, regardless of their party: to the pious and to the enlightened, to the old and to the young, to traditional rabbis and to Crown Rabbis.... come and join the camp of the builders of history! Not every learned or literate person can be a great writer or historian. But every one of you can be a collector of material, and aid in the building of our history.”

In 1936, still a student, Sofer traveled to Vilnius to visit the center of literary, linguistic, folkloric, and ethnographic work at the Yiddish Scientific Institute, known as YIVO. YIVO shared the position that it was the “duty of the Jewish people to collect what has survived and protect it from destruction”

– in response to the destruction of pogroms, but also the growing influences of modernity, such as secularization, urbanization, and the dissolution of rural communities.

Return to Palestine

After Austria’s “Anschluss,”

or annexation, by Nazi Germany in 1938, Sofer re-emigrated to Palestine, specifically Haifa, where he taught singing and drawing at a school, published writings on music education, and owned a music shop.

This stage of his life in Palestine was partly in the shadow of the war in Europe, the reports about the Shoah, and the irrevocable destruction of Jewish life in the region of Sofer’s birth. Meanwhile, Palestine was also the site of ever more frequent attacks and riots and, after the establishment of the state of Israel, the war over Palestine.

X

X

Zvi Sofer outside his small music store in Haifa; bequest of Zvi Sofer, Münster, photographer unknown

Folklore Research and Ethnology

In the late 1940s, Zvi Sofer built on his interest in Jewish history and folklore. Haifa, where Sofer was living at the time, also saw institutional efforts in folklore research and ethnology. An archive of Jewish folktales was established there in the 1950s and became part of the Haifa Museum of Music and Ethnology (since closed) before moving to the University of Haifa. Zvi Sofer was an active supporter of this archive. He was fascinated by objects, but also by collecting stories, jokes, and fairy tales from various cultural groups and time periods. Sofer is said to have been a good storyteller in his own right.

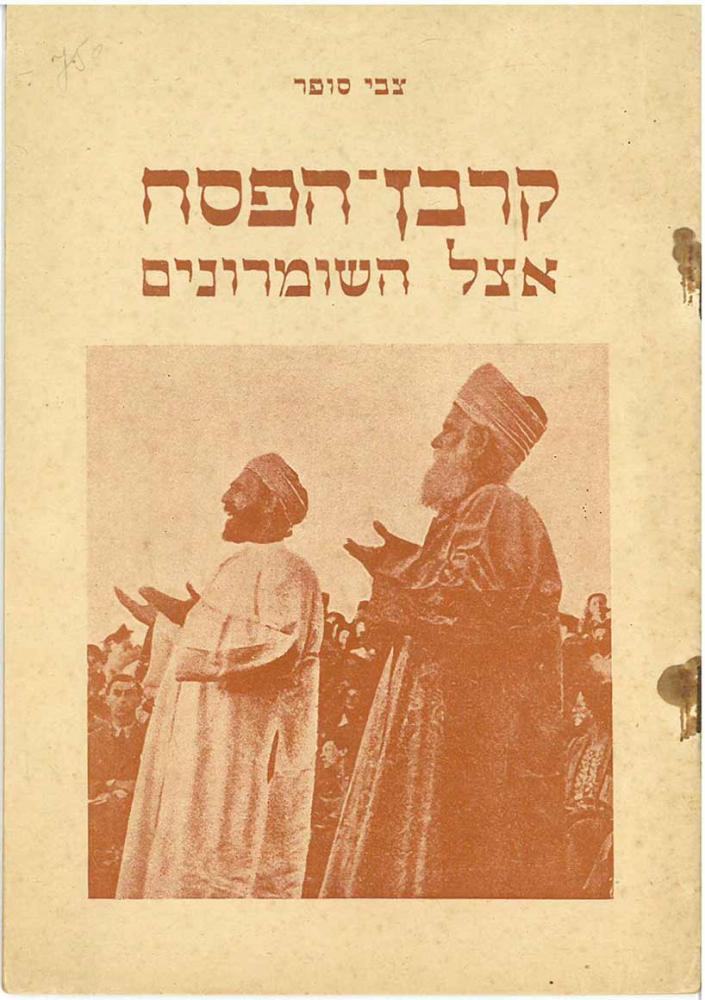

As early as the 1940s, he was conducting ethnological fieldwork on topics such as the Passover traditions of the Samaritans of Nablus. He also wrote scholarly articles about this topic and during this time acquired an object of his future collection: a piece of fabric that is now part of the Jewish Museum’s collection.

Sofer’s Ethnological Fieldwork

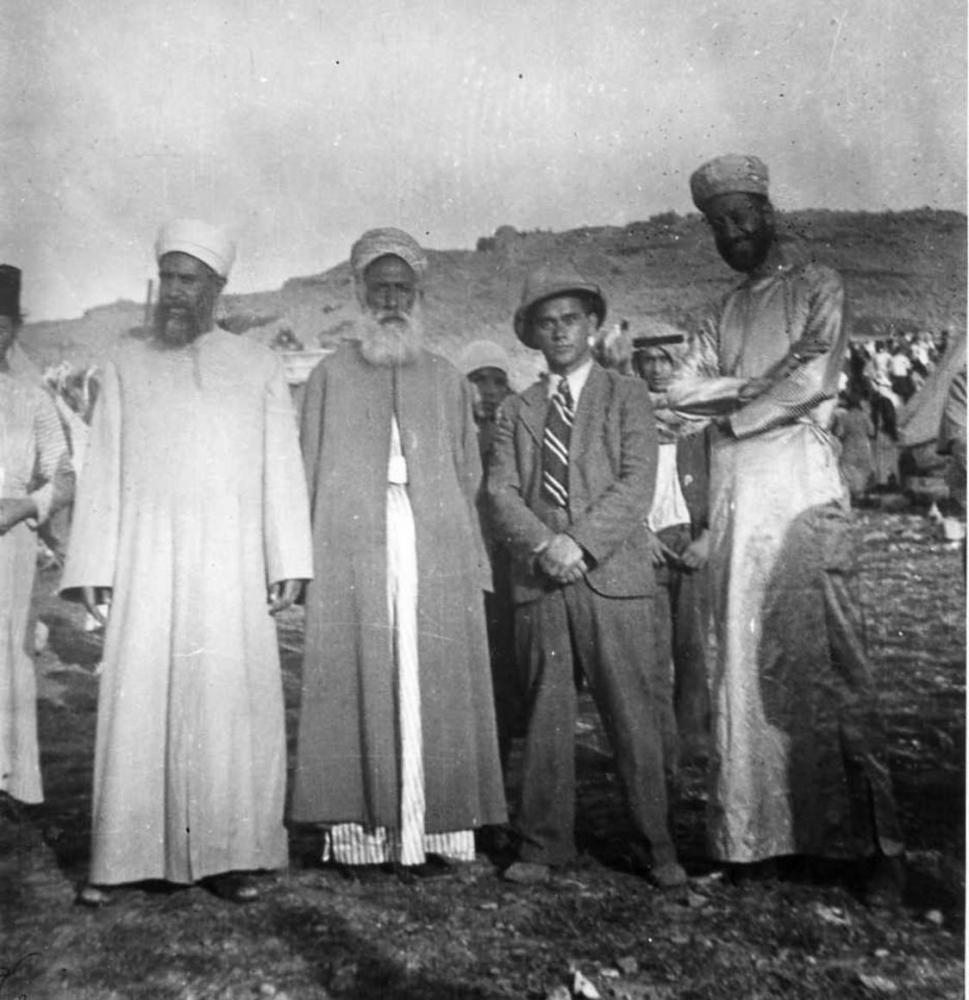

Zvi Sofer (2nd from right) during his ethnological fieldwork in Nablus, before 1952; bequest of Zvi Sofer, Münster, photographer unknown

A Samaritan Torah cloth; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession KGT 81/108/0, purchased with funds provided by Stiftung DKLB, photo: Roman März

Cover of Zvi Sofer’s published research on the Samaritans; bequest of Zvi Sofer, Münster, photo: Anna-Carolin Augustin

In his efforts to expand the Israeli Folktale Archives in Haifa, Sofer became more and more involved in the scholarly disciplines of folklore research and ethnology.

“Inspired by the work I began in Israel for the Folktale Archive, in Germany I primarily devoted myself to studying ethnology.” —Zvi Sofer

Academic Career in West Germany

Between 1959 and 1963, he traveled on behalf of the archive to international conferences of the field known as folktale studies: to Kiel and Copenhagen in 1959, and in 1962 to Antwerp; Paris; Santo Tirso, Portugal; Cloppenburg, West Germany; and Budapest. On his trip to Kiel in 1959, Sofer received an offer from Professor Kurt Ranke to complete his doctorate in folkloric narratology.

Sofer seized the opportunity to resume the academic career that he had been forced to cut short in Vienna. He moved to Kiel and then after two semesters to Göttingen, where he obtained his doctorate in 1965.

After finishing his studies, Sofer received another opportunity in West Germany. In 1966, Professor Karl Heinrich Rengstorf offered him a full-time position as his research associate at the Institutum Judaicum Delitzschianum (IJD) in Münster, which he accepted.

X

X

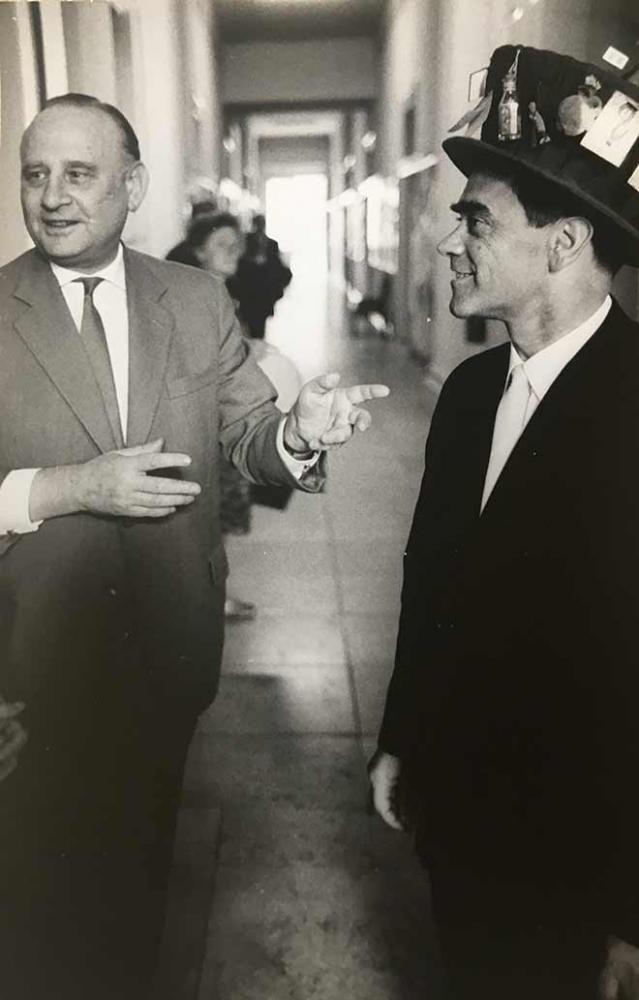

After his doctoral defense, Zvi Sofer (right) with his doctoral supervisor Prof. Kurt Ranke; bequest of Zvi Sofer, Münster, photographer unknown

Interlude: Karl Heinrich Rengstorf

Karl Heinrich Rengstorf was a well-known German Protestant theologian. He was a professor of the New Testament at the universities of Kiel and Münster. After the Second World War, Rengstorf took the initiative to establish the Institutum Judaicum Delitzschianum in Münster under the sponsorship of the Evangelical Lutheran Central Association for Missionary Work among Israel. It was established in 1952 and Rengstorf was its director until his retirement. The original Institutum Judaicum, founded by Franz Delitzsch in Leipzig in 1886, had been dominated by the goal of proselytizing Jews. When it was re-established after the war in Münster, the idea of missionary work receded to the background. From the 1960s onward, the focus was primarily on Christian-Jewish dialogue and contemplating the Christian-Jewish relationship.

Zvi Sofer in Münster: An Outlier

Alongside his publishing projects, teaching at the university in Münster occupied much of Sofer’s time. He taught “Introduction to Jewish Worship and the Prayer Book,”

gave seminars in “Chassidic Legends about the Book of Genesis”

and “Yiddish Poetry from Bialyk and Marc Chagall,”

and taught “Modern Hebrew.”

X

X

The trio: Karl Heinrich Rengstorf (left) with Bernhard Brilling (middle) and Zvi Sofer (right); bequest of Zvi Sofer, Münster, photographer unknown

Zvi Sofer’s courses were highly popular and soon he was surrounded by a circle of enthusiastic students. Along with Rabbi Bernhard Brilling, Zvi Sofer was an outlier at the time in Catholic-dominated Münster.

Beyond his professional life, Sofer dedicated himself to re-establishing and preserving several of the shrinking Jewish communities in northwestern Germany. In the small Jewish community of Lübeck, for example, he served as a prayer leader, religious studies teacher, and eulogizer, leading the congregation every weekend from Friday to Saturday night. He also served as a chazan (cantor) in Essen and Münster.

In the Service of Christian-Jewish Dialogue

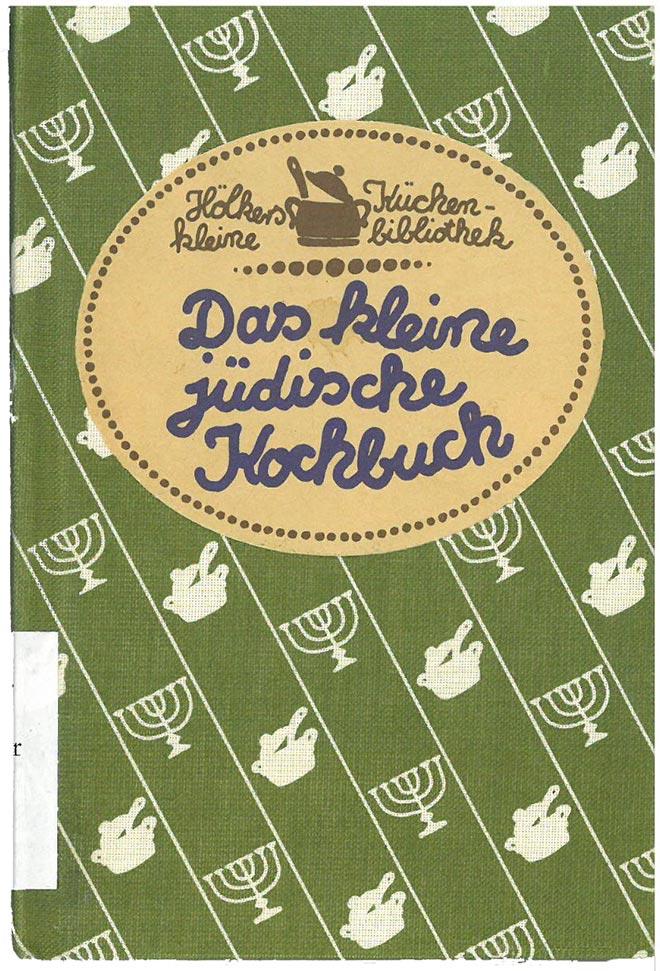

Zvi Sofer was also an important member of the Society for Christian-Jewish Cooperation. Sofer responded to the growing interest in Jewish history and culture in 1960s West Germany by giving synagogue tours, teaching popular courses on Jewish culture at the public continuing education center, and performing concerts of Yiddish music. Sofer also published a Jewish cookbook and two records of synagogue music and popular Yiddish stories by Leib Peretz.

These multifaceted activities in the service of Christian-Jewish dialogue did not go unnoticed. In the autumn of 1977, Zvi Sofer was ceremoniously presented with the Federal Republic of Germany’s Order of Merit with Ribbon, particularly for his efforts to promote understanding between Jews and Christians.

X

X

Cover of Zvi Sofer’s little Jewish cookbook, Hölker publishing 1986; Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Anna-Carolin Augustin

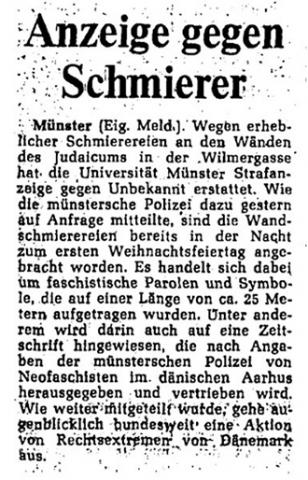

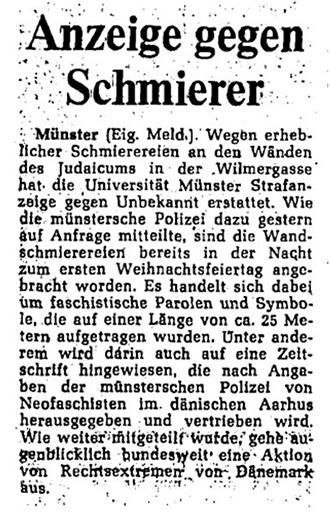

However, the goodwill towards him was not universal. Soon afterwards, on Christmas Eve 1977, the building of the institute where he worked was defaced with a 25-meter-long antisemitic screen and an insignia making reference to him personally. The Dean of the University immediately filed a criminal complaint and told Sofer that he was dismayed and appalled by the incident. Meanwhile, this episode spotlights the ongoing virulent and widespread antisemitism of those years in West Germany.

Sofer Assembles His Judaica Collection

Zvi Sofer would live for only two more years before he died unexpectedly on 25 January 1980. After his death, every corner of his small apartment was found to contain a disorganized jumble of Judaica that he had collected, sometimes in packaging and sometimes out in the open: silver candelabras, lamps, spice boxes, Torah crowns, drawings, books, manuscripts, large-format textiles, and much more.

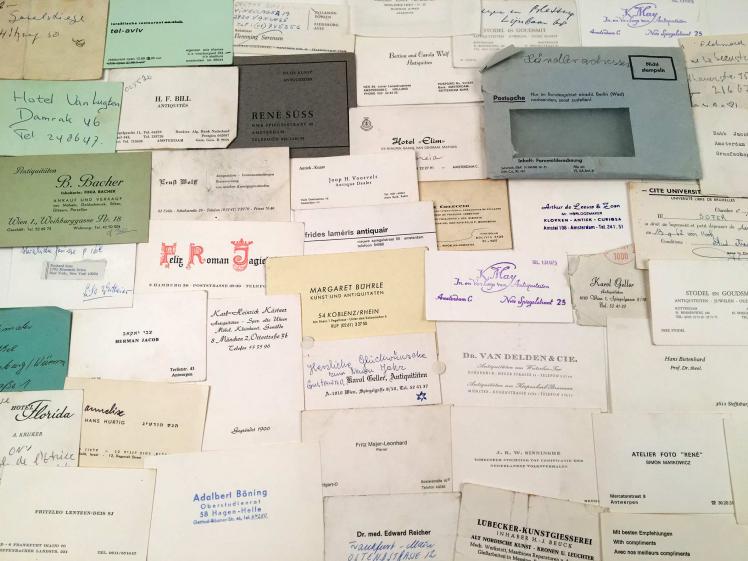

Zvi Sofer presumably assembled his collection unsystematically by making spontaneous purchases from dealers of antiques and art, at flea markets, from individuals, and through gifts. He assembled the objects in West Germany and on trips to other European countries (particularly Switzerland, Belgium, and the Netherlands) as well as Israel. The objects were not cataloged; neither had Sofer documented their acquisition.

However, the collector’s bequest includes another interesting source: a partially annotated collection of business cards that gives indications of dealers, collectors, and other people he knew.

Short article on the antisemitic incident in Münster, Westfälische Nachrichten vol. 301, 29 Dec 1977. Translation: "Criminal Charges against Graffiti Painter. Münster [original reporting] – For substantial graffiti on the walls of the Judaicum on Wilmergasse, the University of Münster has issued a criminal complaint against an unknown perpetrator. As the Münster police told the reporter yesterday, the graffiti was painted on the wall as early as Christmas Eve. It contains Fascist slogans and symbols painted across approx. 25 meters of the wall. The text also mentions a magazine that, according to the Münster Police, is published and disseminated by neo-Fascists in Aarhus, Denmark. The police statement also indicates that there is currently a nationwide campaign conducted by right-wing extremists from Denmark."

X

X

Short article on the antisemitic incident in Münster, Westfälische Nachrichten vol. 301, 29 Dec 1977. Translation: "Criminal Charges against Graffiti Painter. Münster [original reporting] – For substantial graffiti on the walls of the Judaicum on Wilmergasse, the University of Münster has issued a criminal complaint against an unknown perpetrator. As the Münster police told the reporter yesterday, the graffiti was painted on the wall as early as Christmas Eve. It contains Fascist slogans and symbols painted across approx. 25 meters of the wall. The text also mentions a magazine that, according to the Münster Police, is published and disseminated by neo-Fascists in Aarhus, Denmark. The police statement also indicates that there is currently a nationwide campaign conducted by right-wing extremists from Denmark."

Business cards of dealers from the bequest of Zvi Sofer; bequest of Zvi Sofer, Münster, photo: Anna-Carolin Augustin

A remarkable number of the dealers were Jewish themselves and had their own stories of persecution, such as the sisters Bettina and Carola Wolf of Amsterdam and Karol and Gustava Geller of Vienna. In light of the numerous stamps in Zvi Sofer’s passports, one can visualize the routes of his international acquisitions and identify central marketplaces for Judaica in postwar Europe, especially Amsterdam and Antwerp.

Even before the Shoah, the task of conserving physical artifacts of Jewish culture was important to Sofer; after all, he strove to build Jewish history in the spirit of the historian Simon Dubnow. Sofer’s folkloristic and scholarly interests as well as his professional career allowed him to appreciate the Judaica as objects of cultural history. The collection can therefore be considered to be causally related to the collector’s ethnological studies. Sofer also used the objects as a collection of educational materials, as a set of practical examples to display in his talks and seminars, which were primarily aimed at an interested non-Jewish audience.

A Shabbat event with objects from the Sofer collection in Recklinghausen, November 1978 (photo from: Unsere Kirche: Kirchenkreisnachrichten, issue 46, 19 Nov 1978); bequest of Zvi Sofer, Münster, photographer unknown

Exhibitions of His Collection

Because of the “extraordinary interest in the few previous exhibitions on Jewish cultural history and the avid demand for synagogue tours and talks about the world of Judaism,”

Sofer began to organize several traveling exhibitions presenting his collection in the 1970s.

His goal in doing so, as he wrote in the catalog, was “to give a glimpse into synagogues and Jewish homes, both on average days and on holidays, by providing original artifacts and information about customs and rituals.”

He graced the exhibitions in Münster, Lübeck, Duisburg, and Hanover with the caption “May they contribute to mutual understanding between Christians and Jews.”

These regional exhibitions made a tremendous international impact and were reported on in the press across Germany as well as in Austria, Israel, and Switzerland.

A “Wave of Memory” in Germany

The enormous rise in interest about Jewish history and culture that accompanied the “wave of memory” of the 1970s was inversely proportional to the lack of expertise about Jewish life, religious practice, and Judaica. Those who had possessed knowledge about the objects, their use, and their cultural-historical contact had been murdered or had gone into exile. Nevertheless, some of the objects themselves were still around or were circulating freely, following the laws of supply and demand, on the international market in antiques. From the 1970s onward, these objects found their way back to Europe and West Germany with increasing frequency.

Sofer’s dedication to the museum-ification of Jewish cultural history belongs, historically and regionally, within the prehistory and early history of Jewish museums in postwar Germany.

In the 1960s, northwestern German was the epicenter of this development. This region was the origin of groundbreaking traveling exhibitions such as Cologne’s Monumenta Judaica and Recklinghausen’s Synagoga. All of these exhibition projects were temporary, however.

Sofer’s Plan for a Jewish Museum

Sofer was already thinking one step ahead. In the mid-1970s, he saw his collection as a starting point for a yet-to-be-established permanent Jewish Museum and even had concrete plans for it. In March 1975, he met with representatives of the organization for Christian-Jewish dialogue in Cologne to discuss his “Plan to Establish a Jewish Museum in West Germany.”

They agreed on the establishment of a permanent Jewish Museum for West Germany, which, following the model of the Jewish Museum in Vienna, would be a federal institution funded by the budgets of all the West German states and located in Cologne, if possible. When the plan for Cologne fell through, Sofer wrote to the municipality of Essen offering to sell them his collection and explained his plans for a museum in concrete terms:

“Over several decades, I have assembled a Judaica collection. To my knowledge, it is the largest private collection in West Germany. It comprises religious objects, paintings, first editions: altogether, more than 500 artifacts of varying size. The objective of my collection: a permanent Museum Judaicum. It should be attached to an archive for the scholarship and history of Judaism, which would serve as a research center (I also have materials for this in my possession). Together with the available visual and audio records of Essen’s city history, my artifacts, which would suffice on their own for a small museum, could lay the foundation for the first museum of Judaica in Germany.”

In a way, Sofer’s plan would indeed come to pass. After all, the objects from his estate did form the original core of the collection of the Jewish Museum in Berlin. This museum would not open until 2001, more than twenty years after Sofer’s death, but his collection was an important talking point in the political struggle over its establishment and format in the 1980s and 1990s. Thus Zvi Sofer played a part in the institutional history of the Jewish Museum Berlin. Hence, knowledge about the collector’s life and the acquisition of his collection forms part of our own history. In addition, it can be helpful to us today, especially as we try to resolve some open questions regarding the provenance of individual objects from his collection.

Citation recommendation:

Anna-Carolin Augustin (2019), Zvi Sofer. A Collector and His Collection.

URL: www.jmberlin.de/en/node/6035

X

X

X

X

X

X