A Jew Is Not One Thing

The curator about the exhibition “A Is For Jewish”

Miriam Goldmann

If you try to describe today’s Judaism you inevitably run into a classic question: What is Judaism, actually? A religion? A people or nation? A cohesive community with a shared destiny? Or maybe in fact a culture? The exhibition A Is for Jewish: Journeys through Now in 22 Letters sheds light on different aspects of Jewish life in Germany today.

In the Jewish communities in Germany, which are organized as unified congregations, Orthodox Judaism is understood—with only few exceptions—as normative Judaism, and heterogeneity is usually ignored. In recent years, however, an increase in Jewish plurality can be observed: Twenty-six liberal congregations have been founded in the Federal Republic of Germany outside of the unified congregations. Additionally, a number of Jewish initiatives completely independent of religious contexts are evidence of the growing diversity of Jewish identities.

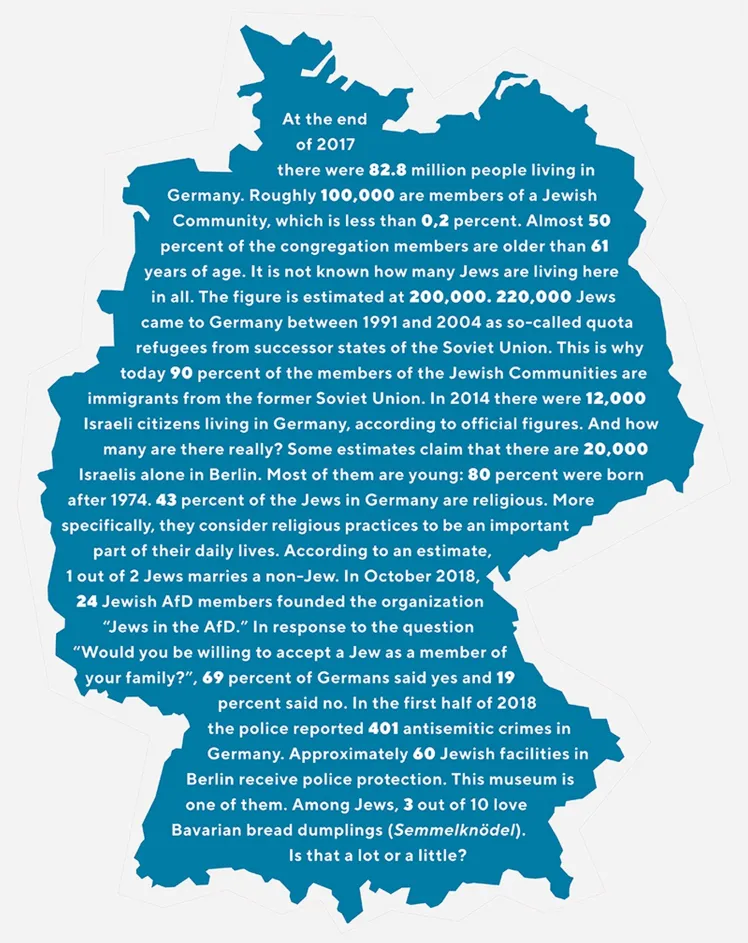

A map of Germany in the exhibition A Is for Jewish presents some numbers. But what do they really say about the facts of life? graphic: Jewish Museum Berlin

With their share of barely 0.2 percent of the total German population, Jews comprise only a minuscule group. About half of these 200,000 individuals are registered as members in the Jewish communities,and the other half moves about outside the official Jewish communities in more or less Jewish contexts. The two groups together make up today’s Jewish community in Germany, including secular and patrilinear Jews. In particular the younger generation of this group at times radically questions German-Jewish tradition up to now. At the same time, the establishment of new Jewish educational institutions has revitalized religious studies in Germany. Critical forums are also emerging on different discourses and questions of identity and positioning within majority society.

Our exhibition aims to offer an insight into this diversity of Jewish life in Germany, including snapshots of the everyday life of both religious and cultural Jews, who are either long-established or recently immigrated to Germany. We deliberately want to stimulate

discussion to question the notion of what is Jewish.

Let Letters Lead You

Within the exhibition each letter of the Hebrew alphabet stands for an aspect of Jewish life and the giant letters direct your glance to present-day Jewish positions. For instance, we open the exhibition with the aleph and the video Twenty two (22) letters by Victoria Hanna; the bet takes up the bar mitzvah or bat mitzvah ceremony, through which boys at age 13 and girls at 12 become adult members of the congregation. Dalet, on the other hand, stands for “disintegration” in the exhibition, a provocative position of mostly young Jewish artists in Germany, who no longer want to be co-opted by Germany’s memory culture.

Other stations shed light on religious festivals and traditions, contemporary music, literature, and art. Modern everyday and ritual objects, paintings, and films by Ashkenazi and Mizrachi, and orthodox, liberal, and secular artists illustrate today’s Judaism. They depict the impressive self-empowerment that has developed within the Jewish community. A special focus has been placed on language—within the structure of the exhibition itself and also anchored in the letter lamed, which portrays writings in the languages written and read by Jews in Germany. Franz Rosenzweig, a philosopher and interpreter of Judaism, wrote an article in 1925 asserting that Hebrew, this ancient language, can never become one of the so-called dead languages. Just the opposite: Hebrew, through all ages, has always developed further and has continuously incorporated external influences. The language, independent of its function as the state language of Israel, contains an identityforming aspect beyond national boundaries, which offers a home to many Jews.

X

X

This cut-out kippah was distributed at the festival Disintegration: A Congress on Contemporary Jewish Positions, held at the Maxim Gorki Theater in May 2016; Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Roman März

Some stations of the exhibition

א

For the first letter, “Aleph” the exhibition was dedicated to the “aleph-bet” itself, for example, with Victoria Hanna’s video art Twenty Two Letters, Israel, 2015; copyright: Victoria Hanna.

ב

In the exhibition, “Bet” stood for bat mitzvah. The photo shows Mussi Bistritzky during her bat mitzvah speech. Her father, Shlomo Bistritzky (an orthodox Landesrabbiner of the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg, as well as leader of the Hamburg Chabad Center), is adjusting the microphone; Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Gesche M. Cordes.

ד

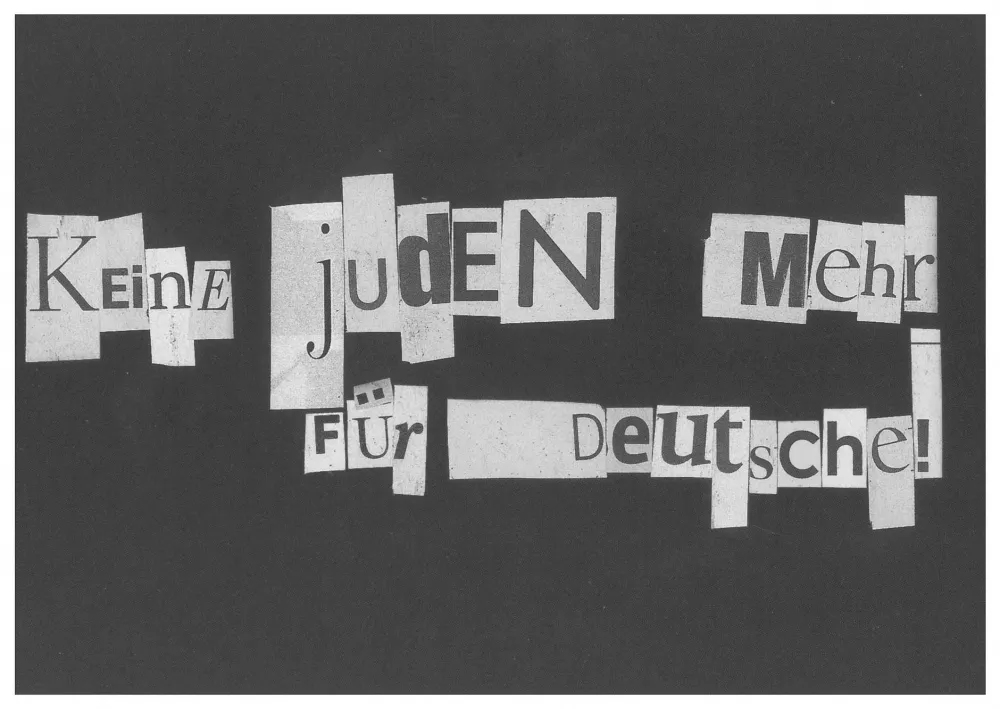

The letter “Daled” stood for “disintegration” which describes a provocative movement of a new generation of Jewish artists who no longer want to be considered victims by German remembrance culture. Postcard from the festival “Disintegration: A Congress for Contemporary Jewish Positions” at Studio Я of the Maxim Gorki Theater in Mai 2016; conception Max Czollek, Sasha Marianna; design: Deniz Keskin

נ

Who knows the “Jewrovision?” – for the keyword “Youth,” the exhibition presented the largest Jewish song and dance competition for children and young people, at which around 1,200 participants presented their interpretation of the Jewish Circle of Life at the beginning of 2018. Kippot memorabilia Jewrovision 2018; Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Roman März.

ק

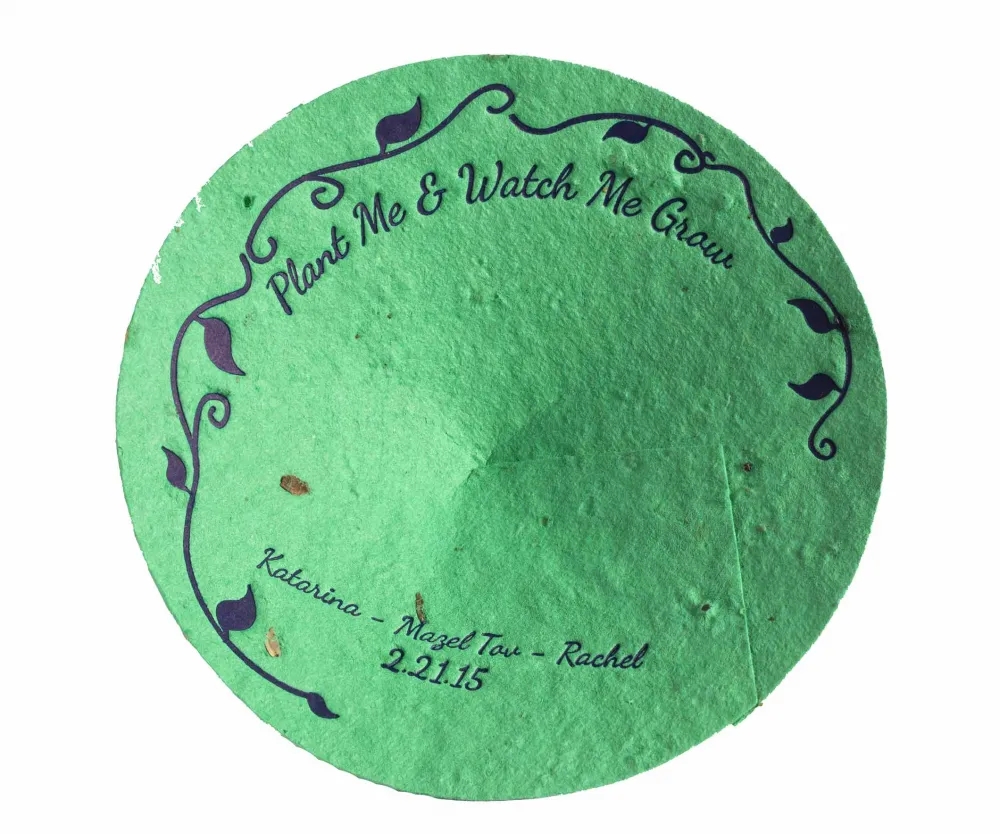

For the letter “Kuph,” the exhibition explored the topic of weddings. It also playfully reinterpreted the museological concept of the “contact zone”: the Jewish Museum as a place where visitors can encounter the love of life—as the musician Daniel Kahn and his wife Ewa Lapsker did; they also held their wedding here at the museum. The kippah containing seeds (pictured) is from the wedding of Katarina and Rachel; Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Roman März.

ר

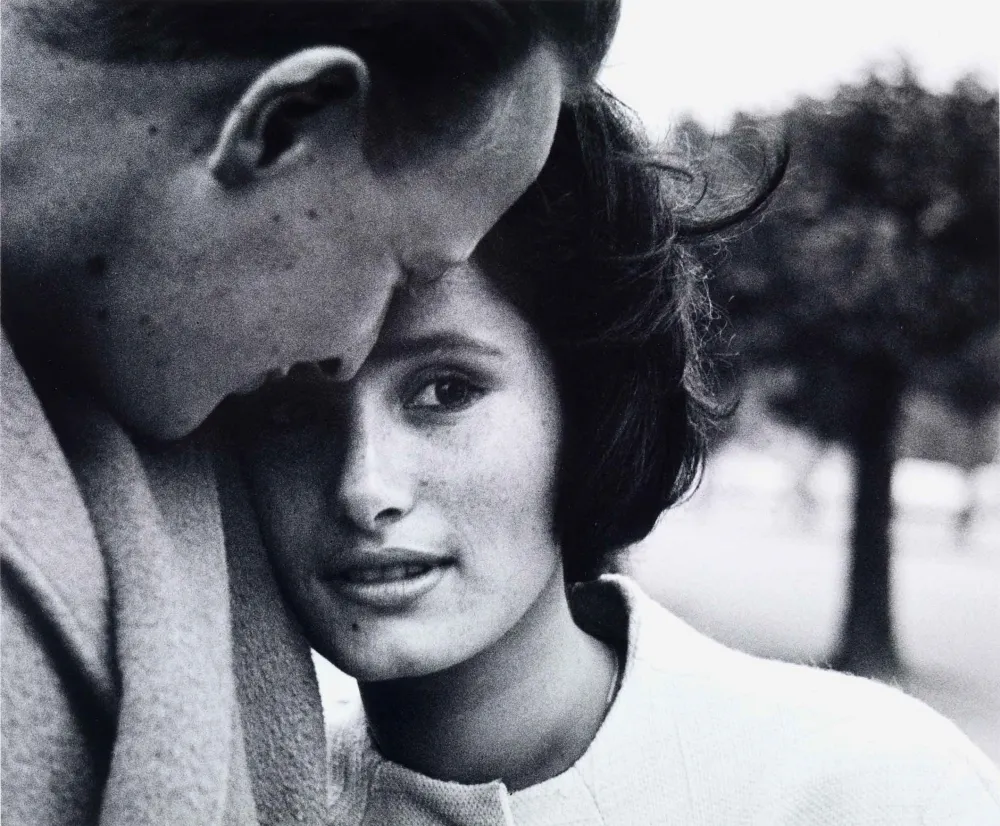

Along with new ideas brought by Russian-speaking immigrants, Jews who have long been based here were also part of the exhibition. This photo by the famous photographer Leonard Freed from our photography collection (more at our website) belonged to the letter “Resh” because the couple’s last name is “Rubinstein.” Leonard Freed, A Young Jewish Couple from Düsseldorf. From the series “German Jews Today,” Düsseldorf 1961; Jewish Museum Berlin

ת

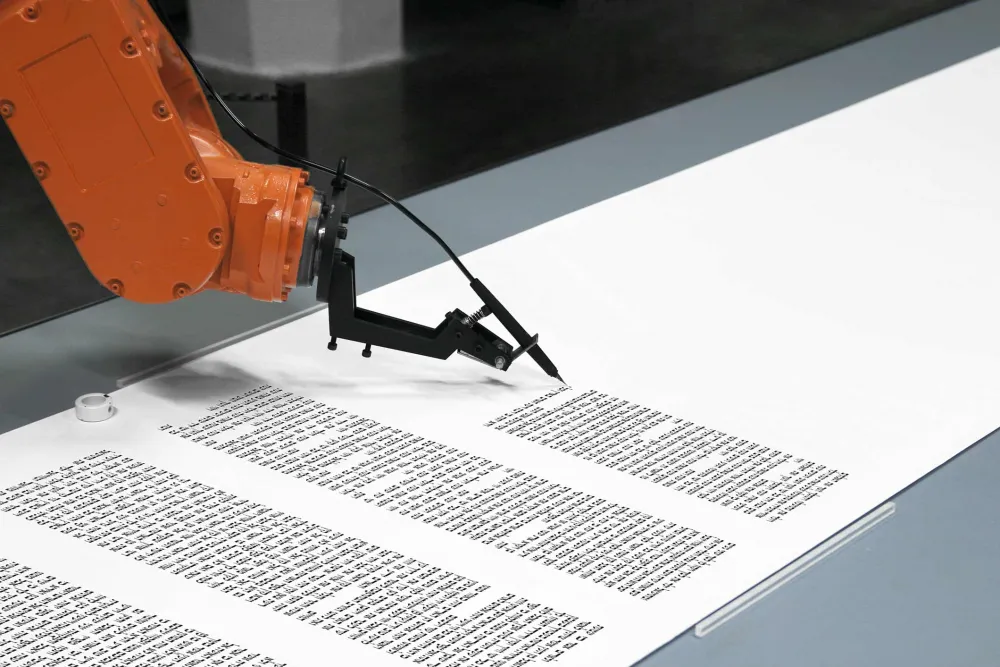

For the last letter of the “aleph-bet,” “Tav,” the exhibition engaged with the Torah, for example, with the installation bios [torah] by the artist collective robotlab, in which a robot wrote a Torah here in the museum in 2014/2015 (read more on the installation); photo: robotlab.

As this view of the exhibition A Is for Jewish shows, there were many more informative and entertaining stations. In the letter כ (“Kaph”) for “kosher,” for example, you could find a vending machine with kosher gummi bears (for the meaning of the term “kosher,” see the topic “Kashrut” on our website); Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Yves Sucksdorff.

ה

Young Russian-speaking Jews have drawn their Berlin on four mental maps. The maps are part of a PhD thesis entitled Generation "kosher light". Alina Gromova from Academy Programs introduces you to the letter "He", which stood for "Home" in the exhibition; Jewish Museum Berlin 2020. (in German)

ט

“Tet” is the ninth letter of the Alef-Bet. What role does its numerical value 9 have in the Jewish culture of remembrance? This question is answered by Alina Gromova from the Academy Programs in the video; Jewish Museum Berlin 2020. (in German)

מ

At the letter "Mem" the exhibition was about the mitzvot, the commandments in Judaism. In this video, Miriam Goldmann, curator of the exhibition, introduces you to the station; Jewish Museum Berlin 2020. (in German)

ר

At the exhibition station on the letter "Resch" was also displayed a photograph from 2018. On it, the Rubinstein couple recreated the photo from 1961. Theresia Ziehe, curator of photography, tells how the photo was taken; Jewish Museum Berlin 2020. (in German)

ת

The letter “Taw” is also part of our digital tour through the exhibition. In this video, Miriam Goldmann, curator of the exhibition, gives you some background on the Torah scroll written by a robot and introduces the painting Mes amies et moi by Barbara Honigmann; Jewish Museum Berlin 2020. (in German)

Jewish Immigration

Jews from the countries of the former Soviet Union, who now make up about 90 percent of the Jewish communities in Germany, brought a new sense of identity to the country. They view themselves as victors in the “Great Patriotic War” and celebrate the “Day of Victory” on May 9. This provides new impulses, taken up especially by the younger generation, for the German-Jewish memory culture. But Russian-speaking Jews also brought a different cultural and religious identity with them, often leading to conflicts. The ostracism of Jewish citizens in the Soviet Union took place through an ethnic classification based on the father’s lineage. Not all Russianspeaking Jews therefore fulfill the halakhic condition of having a Jewish mother in order to be accepted into a Jewish Community in Germany. Consequently, the communities were faced with the question of how to deal responsibly with children who can claim only a Jewish father. Through their identification with their paternal family, these patrilineal Jews often have a very strong Jewish identity and are generally perceived as Jewish by their non-Jewish environments.

X

X

Pin for the 70th anniversary of liberation on 9 May 2015. Central Council of Jews in Germany, Metall, Berlin 2015; Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Roman März

The Jewish community in Germany has also grown considerably in recent years due to the influx of largely very young Israelis. Although only a very small portion of them have any interest in the official Jewish communities, and very few of them wish to live religious lives, virtually all of them consider themselves Jewish. Through these Israelis the question as to the meaning of a secular Jewish identity has gained significance in Germany: Can Judaism be more than a religion?

Starting From Here and Now

It is no coincidence that the exhibition starts with aleph, the first letter, and ends with tav, which here stands for the Torah, as language and Holy Scripture are the two most important pillars of Judaism. What place do Hebrew and the Torah hold in Germany today? Hebrew was declared the Holy Language by rabbinical authorities, and the Hebrew Bible is the point of reference for all things Jewish. Jewish scholars have debated with each other for centuries over the interpretation of the Torah. Their discussions and decisions have been passed down through the Talmud and are not only part of present-day tradition, but continue to be debated even today—also in Germany. After the Shoah the Jewish denominations that had developed in Germany where exported, continuing in the twentieth century, especially in the United States. Today, however, we can observe these Jewish schools of thought returning to Germany: Large, often orthodox organizations are present here in the form of religious schools, but also

grassroots movements are gaining strength by importing modern interpretations and their practice. This kind of debate is as old as Judaism itself and continues to take place today. It is a rare occurrence when Jews agree on a definitive answer. But perhaps a one-dimensional response is not absolutely necessary in these times in which religiosity seems to be just one of many possible ways of life, and secular “hyphenated identities” receive greater attention. At a sociopolitical level we are presently experiencing the significance of open debates outside of ideological trenches. Religious communities are particularly susceptible to the pressures of social change and are all the more dependent on engaging in an open discourse, not only with their own members but also with the vaguely defined circle of potential members, and on abandoning the narrowness of ideological echo chambers.

Or, to put it another way, quoting the Jewish Museum in New York: “A Jew is not one thing.”

Miriam Goldmann is one of the curators of “A Is for Jewish: Journeys through Now in 22 Letters.” She studied Jewish Studies in Freiburg, at the Hebrew University Jerusalem, and the Freie Universität Berlin. She has been working at the Jewish Museum Berlin since 1999.

This article was first published in 2019 in issue 20 of the print edition of the JMB Journal.

Citation recommendation:

Miriam Goldmann (2019), A Jew Is Not One Thing. The curator about the exhibition “A Is For Jewish”.

URL: www.jmberlin.de/en/node/6301