“The best solution would be that the baby is a girl”

Insights into an Internal Jewish Debate about Circumcision in 1919

Shortly after the opening of our exhibition Snip it! in 2014, the Jewish Museum received as a bequest the estate of Fritz Wachsner (1886–1942). Included in this delivery was a bundle of letters so enormous that I didn’t have time, in creating an inventory, to delve into each individual piece.

But one letter caught my attention.

“[…] Your assessment of the circumcision issue […],” wrote Wachsner on 24 July 1919 to his – then very pregnant – wife Paula’s uncle Anselm Schmidt (1875–1925). I read on and suddenly found myself in the middle of a nearly one-hundred-year-old internal Jewish debate on circumcision.

At the time, Fritz Wachsner was 33-year-old teacher in the town of Buckow in Brandenburg. In the five-page letter he clarifies the reasons for his hostile stance towards the Brit Milah.

What is the Brit Milah?

Brit Milah (Hebr. for covenant with the word), also called Bris, circumcision, ritual removal of the foreskin on the eighth day of life, symbol of the contract between God and Israel

He was an assimilated German Jew and belonged to a Reform Jewish congregation. As he explains to his uncle, he was “raised fairly orthodox” but, in the course of his university studies in Berlin and Jena as well as at the Academy for the Study of Judaism in Berlin, he learned “to know and appreciate the spirit of Judaism freed from every non-German embellishment.” He became persuaded that the religion should evolve continually and be “modernized and improved.” Wachsner’s maxim was: “Become German, outside as well as inside the religious community,” the overtones of which are especially bitter when one learns that on 5 September 1942 he was deported to Riga and murdered there.

In the letter to Anselm Schmidt, Wachsner invokes above all “religio-historical” arguments to defend his opposition to circumcision: it goes back to the pagan rituals of human sacrifice, he writes, that were vanquished with the “introduction of monotheism” to the extent that, henceforth, “instead of a whole person” now just the foreskin would be sacrificed. In his opinion, circumcision was an “oriental-pagan” custom that was ultimately alien to Judaism. He rejected the view that the practice is a sign of the covenant between God and his people. In reality, he believed, belonging to Judaism was defined entirely by a person’s “acknowledgment of the one true God.”

X

X

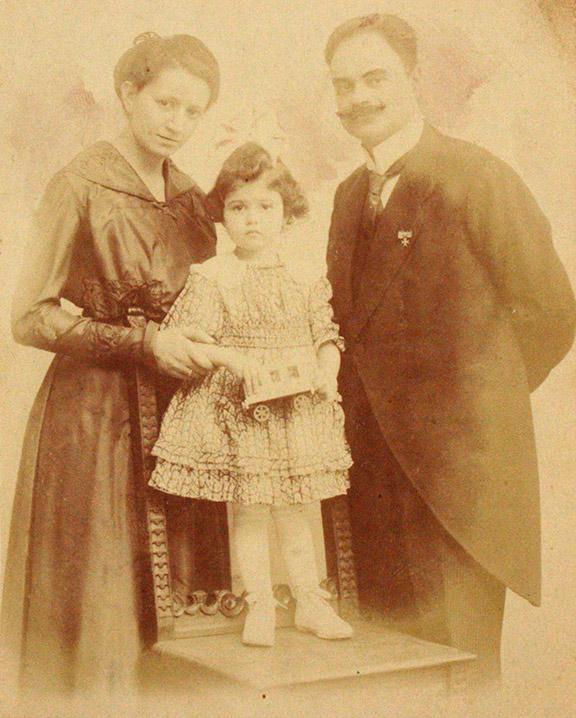

Fritz Wachsner with his wife Paula and their first-born child, Charlotte, studio portrait, ca. 1916; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2014/312/1, gift of Marianne Meyerhoff, photo: Jörg Waßmer

Particularly with his “terribly upright” parents-in-law in Upper Silesian Gleiwitz, but also with his own parents in Berlin, Wachsner encountered incomprehension when it came to his disapproving position on circumcision. He refused to yield to family pressure however, and claimed for himself the right and even the duty to act according to his convictions and “remain honest before God and the world,” even at the risk of “grieving” his relatives.

After reading this letter I looked through the entire correspondence over the summer months of 1919 to examine whether the topic of circumcision was discussed further. In fact, there are seven letters in total, from a variety of correspondents and through them we can reconstruct the agitation on this subject that reigned in the Wachsner household during the last months of the pregnancy.

One letter dated 27 July 1919 is from his uncle and “fatherly friend” Leo Timendorfer (1855–1927). It appears that Wachsner included him in the discussion from the very beginning, with Timendorfer reinforcing his opposition. In a later letter, written on 30 August 1919, the older gentleman explained his own stance against circumcision.

Wachsner’s mother Fanny (1857–1942), meanwhile, wrote to her son on 8 August 1919: “One doesn’t know yet what God has sent you, but one must plan for either; whether a girl or boy, either one will be as dear to you as the other. We simply want the baby to be healthy and that the mother doesn’t suffer too much.” Should the baby be a boy, she asks her “dear, beloved Fritz” to circumcise him. The ritual would, it’s true, “not be in keeping with the times,” but it wouldn’t hurt anyone. Arguing very pragmatically she conveys to him how little effort the Bris would cost him: “The two grandfathers and you, that would entirely suffice.” His father would bring a mohel, who would provide the “treatment” and “check back in,” so that a doctor would not be necessary.

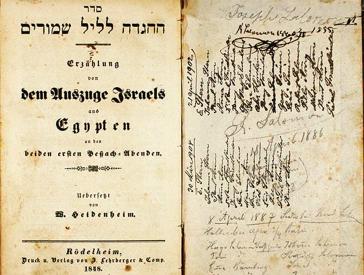

X

X

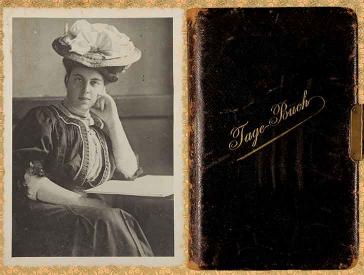

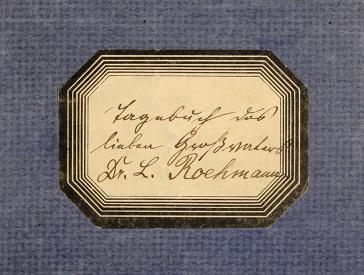

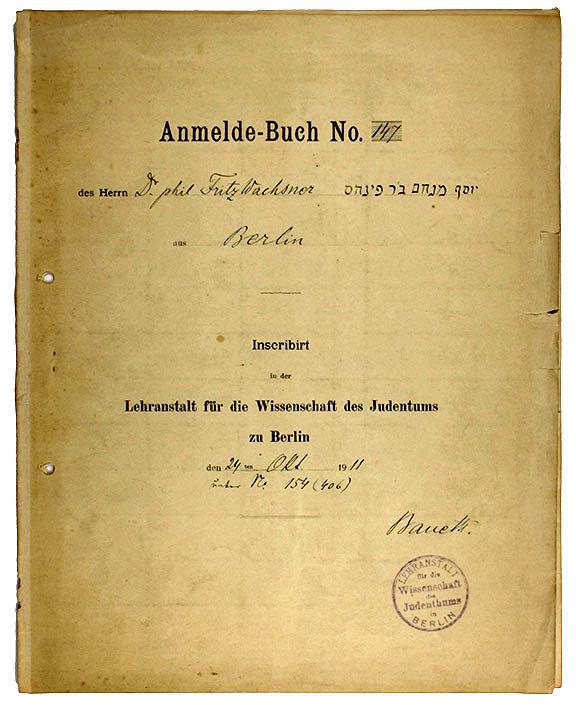

Fritz Wachsner’s exercise notebook from the Berlin Academy for the Study of Judaism, title page, 1911–1913; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2014/194/98, gift of Marianne Meyerhoff, photo: Jörg Waßmer

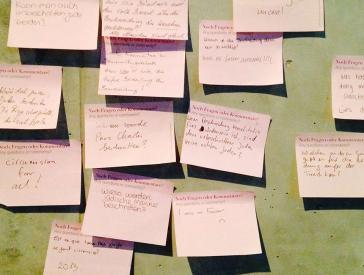

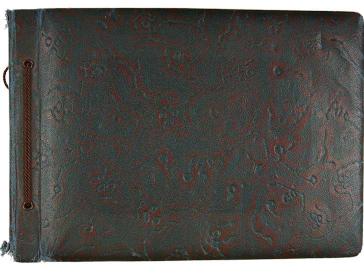

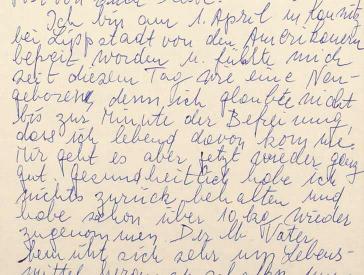

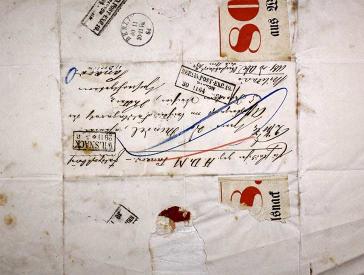

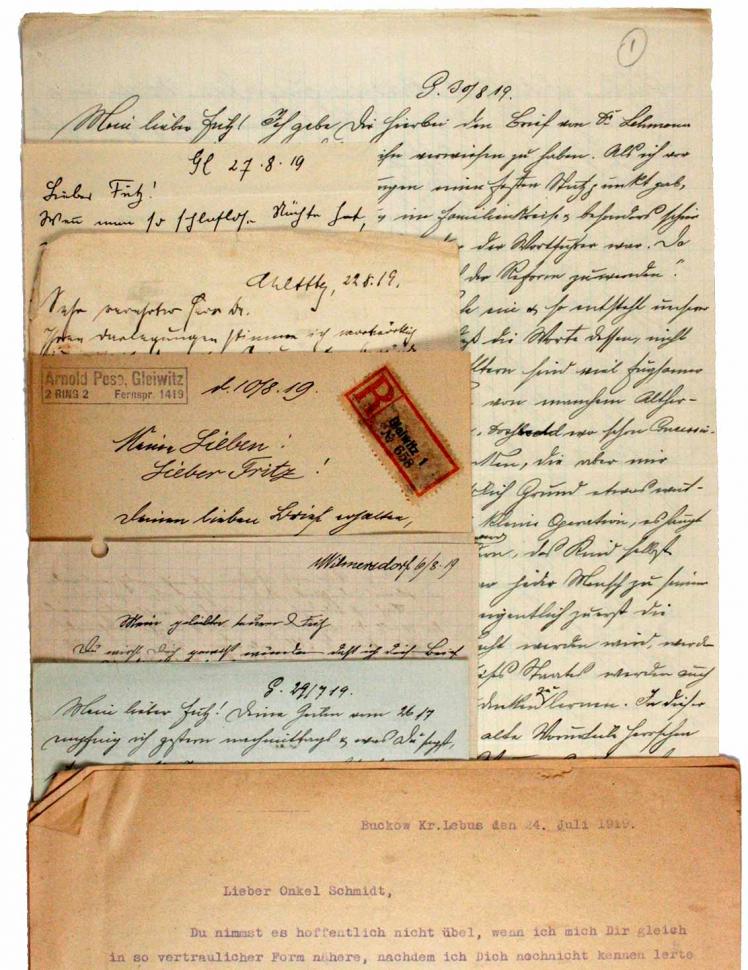

Correspondence to and from Fritz Wachsner regarding the pro and contra on circumcision, 29 Jul–30 Aug 1919; Jewish Museum Berlin, gift of Marianne Meyerhoff, photo: Jörg Waßmer

Two days later Wachsner’s father-in-law Arnold Pese wrote. The owner of a “House, Kitchen, and Hotel Equipment Supply” business felt compelled to react despite barely feeling himsel capable of his scholarly son-in-law’s level of argumentation: “Even if I can hardly be master of the erudite lines you wrote, I will try to express my point of view.” Pese rejects Wachsner’s derogatory remark that circumcision is only “a common Oriental practice.” It is a “commandment and law in our Talmud.” Citing the Torah, Pese emphasizes “the importance of circumcision” as a sign of the covenant with God. He veritably implores Wachsner to change his position and signs off “with heartfelt regards.”

The bequest also includes a letter from Dr. Joseph Lehmann (1872–1933), a pioneer of the Jewish reform movement and preacher at various liberal synagogues in Berlin. The Joseph Lehmann School in Charlottenburg would later be founded, in 1935 after his death, named for him, and have as its first director none other than Fritz Wachsner. In his short letter to Wachsner on 22 August 1919, Lehmann “concurs” with Wachsner’s “explanations, chapter and verse.”

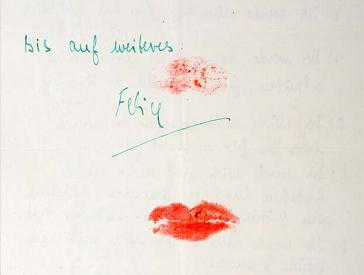

The due date approached apace. On 27 August 1919 Wachsner’s mother-in-law Adele Pese (1871–1942) also entered the fray: she confessed to him that she spent “sleepless nights” on account of the quarrel. In great distress about the wellbeing of her daughter, she begs Fritz Wachsner, “not to tell Paula at the birth if it’s a boy, but to wait a bit,” so that she won’t “get too upset.” “The best solution would be that the baby is a girl,” Pese concludes in her letter.

At last the baby came: a boy, Ernst, born on Sunday, 31 August 1919. Whether he was circumcised eight days later is not revealed by further documentation. There are no congratulations on the occasion of a Bris, but this doesn’t say much, since the family collection remains only in fragments. It did not, at least, come to any rupture in the family. They remained in cordial contact.

Jörg Waßmer, Archives, prepared the inventory of Fritz Wachsner’s estate.

X

X

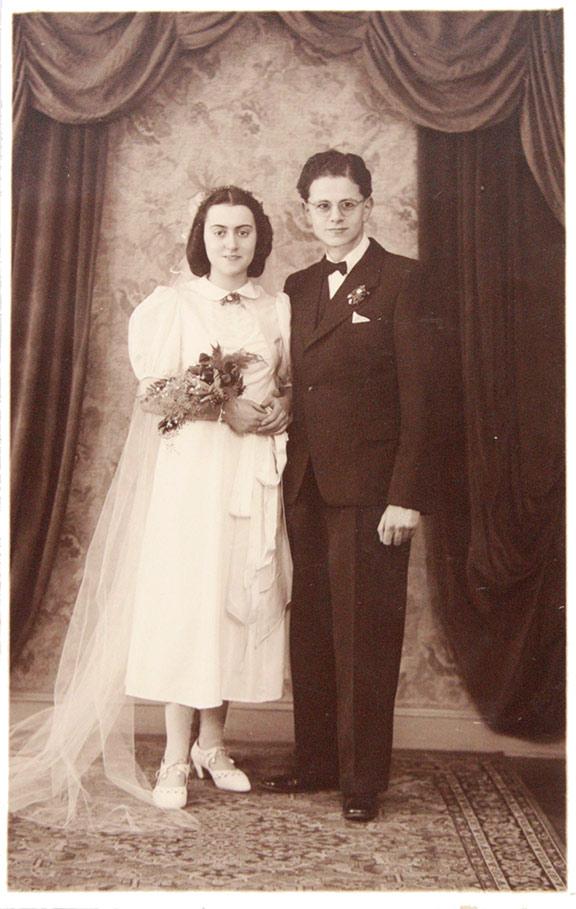

Ernst Wachsner and his wife Margot were deported on 1 March 1943 to Auschwitz, where they were murdered. He was only 23 years old; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2014/194/545, gift of Marianne Meyerhoff, photo: Jörg Waßmer.

Citation recommendation:

Jörg Waßmer (2015), “The best solution would be that the baby is a girl” . Insights into an Internal Jewish Debate about Circumcision in 1919.

URL: www.jmberlin.de/en/node/6563

Behind the Scenes: Entries on the Exhibition “Snip it! Stances on Circumcision” (9)

Behind the Scenes: Anecdotes and Exciting Finds while Working with our Collections (22)