Lucky Coincidences

Interview with our New Museum Director Hetty Berg

Hetty Berg assumed the directorship on 1 April 2020; Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Yves Sucksdorff

Hetty Berg, born in 1961 in The Hague, studied performance studies at the University of Amsterdam and management at the University of Utrecht. She worked first as a curator and cultural historian at the Jewish Historical Museum Amsterdam and from 2002 as the museum manager and chief curator. In 2012 the JHM expanded into the city’s Jewish Cultural Quarter. In November 2019, the Board of Trustees of the Jewish Museum Berlin unanimously voted to appoint her as the new Director. She assumed the directorship on 1 April 2020.

Dear Hetty Berg, starting as new Director of the JMB you are confronted with very special circumstances: the city – as almost all of Europe – is at a standstill because of the Corona pandemic. How did that influence your arrival in Berlin?

We drove from Amsterdam to Berlin by car. That alone was very unusual ‒ because the motorway was almost empty! The museum is closed, many of its employees work from home. But on the very first day I spoke with over 100 colleagues via video conference and answered many questions. Of course I had imagined my start at work quite differently! Nevertheless, it is always good to be on site.

How are your first days at the JMB shaping up?

Despite the special situation, I use this time to get to know the museum and the staff. We have online meetings to learn about the perspective and challenges of the different departments. We are developing alternative online offers for the sudden closing time. But the most important thing is that together we find solutions on how best to work collaboratively during the Corona crisis, even though direct, personal exchange with each other is missing.

You were born in the Netherlands and spent much of your life in Amsterdam. What are your impressions of Berlin?

Thinking back, all my trips to Berlin were connected to Jewish culture and history. My first visit to Berlin was the summer after the Wall came down, but the first time I spent a little more time here was on the occasion of the exhibition Patterns of Jewish Life in 1992. Ten years later, preparing for the renewal of the Joods Historisch Museum (JHM) in Amsterdam, we took a study trip to all the Jewish sites and memorials in Berlin. I remember a wonderful visit to the newly opened and impressive JMB, where we talked with the museum’s managers Ken Gorby and Nigel Cox. Then, of course, I came to Berlin and to the JMB for the opening of Heroes, Freaks, and Super-Rabbis: The Jewish Dimension of Comic Art, because I was one of the curators of the initial exhibition.

Despite these trips, I got to know the city properly only fairly recently. When my partner, photographer Frédéric Brenner, was a fellow at the Wissenschaftskolleg zu Berlin in 2016‒2017, I spent seven months here and met many interesting people. I carried out a research project that compared the permanent exhibitions of Amsterdam’s Jewish Historical Museum, the Jewish Museum Berlin, and the New Synagogue Berlin – Centrum Judaicum, and looked into the redevelopment processes these museums had embarked upon.

Could you tell us why you became a curator – a “museum woman”?

I studied Performance Studies, for which I had to do archival research. Through the archivist Joel Cahen, who was then curator at the JHM, I became an intern at the there in 1986. At the time, the JHM was preparing to move to the Ashkenazi synagogue complex, where it has been located since 1987. I did research in many different archives all over the Netherlands, looking for information and documents and photos to be used in the permanent exhibition. After that, I became assistant curator. And I never left, or not till very recently!

I worked in all aspects of museum affairs, including permanent and temporary exhibitions, and led the renewal of the JHM in the early 2000s. I ended up staying for more than thirty years and becoming chief curator. I didn’t plan for a career in the museum world, it happened by chance, just one of those lucky coincidences.

You can certainly look back on many years of experience in museum work. Is there still something new that you’re looking forward to?

Yes, working for a Jewish museum in Germany is a very different matter from working for a Jewish museum in Amsterdam – the historical and social context differs considerably. Emotionally, it’s a big step, and that, too, is part of the meaning of moving to Berlin for me! But through my research I had already engaged with the JMB’s work, and as I’ve been working in the Jewish museum world for many years, I know a number of colleagues here. I am very grateful for these relationships and for the new ones I am building. It made my start at the JMB much smoother. In particular, I’m greatly looking forward to contributing everything I’ve done in the past – along with many new ideas – to a much larger museum that also has great significance symbolically and internationally.

You were chief curator of the Jewish Cultural Quarter in Amsterdam for many years. The Jewish Museum Berlin also extends across several buildings and sites. Do you see resemblances?

The beauty of the Jewish Cultural Quarter in Amsterdam is that it combines so many aspects of Dutch Jewish history and culture within five different buildings: the Jewish Historical Museum; two Holocaust-related sites, the Hollandsche Schouwburg memorial and the National Holocaust Museum; the Portuguese Synagogue, an active synagogue and library; and the Children’s Museum. This variety of venues and contents attracts visitors with very diverse interests.

The same is true for the JMB: it’s a multi-venue cultural hub including the museum with different exhibitions, the academy, ANOHA (the children’s world at the JMB), the library, and the gardens. Each venue’s activities target a different audience, yet at the same time they have to be coherent! That means the organization is complex, but it is a wonderful opportunity for the different aspects to complement each other.

The challenge for the JMB is that the different venues mustn’t compete with one another, but rather work together to fulfill the mission of the Foundation. Many people work for different parts or venues, but they also have to keep in mind the organization as a whole. It is important to distribute attention and resources in a balanced way.

The Jewish communities of Amsterdam are very diverse. What are the special features of that city, and are there similarities with Berlin?

The Jewish communities of Amsterdam are largely a continuation of the prewar Jewish communities: the Ashkenazi and Portuguese Jewish communities and the Liberal community. More recent developments such as Beit Ha’Chidush (House of Renewal) are initiatives by people who are looking for a different offer. Also, today there are many Israelis in Amsterdam. There is an alternative scene, such as young people organizing their own minyan once a month or Oy Vey, an inclusive meeting place to experience contemporary Jewish culture. But this is all happening on a very small scale.

During my stay in Berlin in 2016‒2017, I attended services in many synagogues of various traditions. I was really excited by the range of different ways in which Judaism and Jewish culture are expressed in Berlin, including in unexpected settings. What is Jewish in Berlin is changing; it is very dynamic, and there is a new generation from very diverse backgrounds with plenty of ideas. People think a lot about what it means to be Jewish here – whether privately among friends or publicly. That is unique and, of course, has a lot to do with Germany’s history and culture. The JMB can offer a positive contribution to this fascinating and multifaceted development of Berlin Jewry as a center for Jews in Europe.

The Jewish Museum Berlin in the southern Friedrichstadt in Berlin-Kreuzberg; Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Jens Ziehe

The JMB is located in the middle of a neighborhood that is changing rapidly and calls for close neighborly relations between different cultures and religions. What opportunities does that create?

The JMB has impressive numbers of international visitors, and of course that’s wonderful – but one of our goals has to be to reach a German audience as well: Berliners, and especially the people who live near the museum. I think the new children’s world ANOHA will have an important role to play in reaching out to those groups, Berlin families from the streets right near the museum, but also from other parts of the city. ANOHA will welcome many school students with all sorts of different backgrounds, children who may never have been to a Jewish museum before – or perhaps never visited a museum at all. Ideally, they will come back with their families, so that the adults also get to know the museum or want to visit a particular exhibition. Surrounded by growing tensions between the diverse cultures coexisting in a district like Kreuzberg, the museum can be a place for people to encounter each other, exchange views, listen, and come to understand each other better.

In recent years, discursive and participatory ideas for museums have frequently been discussed and put into practice. What’s your opinion of such approaches, and where do you see additional opportunities?

Museums face a double task. On the one hand, they are the caretakers of the collections; on the other, they need to represent the collections to the public. Because societies and audiences change all the time, you have to adapt your strategies on connecting with the visitors. You can’t approach visitors in the same way as in the 1980s or even the 2000s. I think it’s important to explore all these ways of engaging with audiences, without saying that you always have to be participatory.

One of the important new approaches of recent years is that exhibitions in a museum can be multi-focused, show multiple perspectives: the audience is not exposed to a single, authoritative narrative, but can experience different voices, viewpoints, and opinions.

Many museums are trying to make their collections accessible online, offering apps to guide visitors around the museum and creating online exhibitions or the option of public participation through the Internet. What are the potential advantages of digitalization for museums?

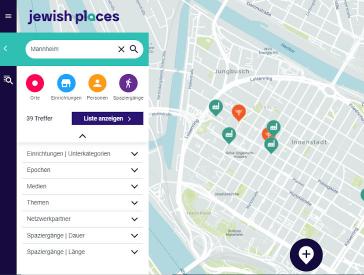

Digitalization is a driving force in the transformation of the heritage field, and digital formats are a crucial way of reaching new visitors. The JMB is an institution with extensive experience in that respect. A wonderful example is the JMB’s platform “Jewish Places,” which shows how the digital world changes relationships with the audience. Visitors to the platform have an active role: they can contribute what they know and even upload images or film. People in any city can really engage with Jewish culture through the website.

In Amsterdam, we have the platform “Joods Monument,” Jewish Monument. It is Holocaust-related and dedicated to all the Jews who were deported from the Netherlands and killed. On the platform you can find their last addresses and information about them. It is linked to the collection of the JHM, so you can also find objects connected to the person’s history on the website. Several years ago we started a community for the platform, so everyone can upload information now – and it’s really grown. It’s incredible!

Offers like these mean we can actually have many more digital than physical visitors. Digital visitors are a target group in their own right, the largest audience most institutions will ever have. But it’s not only about showing: what I like a lot is the participatory aspect, as people can comment on objects they see online, and these comments may give the museum important information and insights into its own collections. After all, the collection – digitized or not – remains the core of any museum.

In your view, what role can and should the JMB play in Berlin’s – and more broadly, Germany’s – increasingly polarized society?

The JMB must continue to be a socially relevant location where open encounters and open debates can take place. It is situated in a productive field of tension: on the one hand, its task is to provide a reliable guide to Jewish history and culture in Germany; on the other, it faces the challenge of addressing the dynamic and complex developments in present-day German and German-Jewish society.

To do justice to that dual mission, the JMB needs to be an independent forum and a free, protected space where all the relevant social issues can be discussed. Among other things, that includes exile and migration, exclusion and integration, identity and diversity. The JMB should be a place where conversations with real depth and substance can happen. It should take the pulse of society, and use that as a perspective to communicate contexts and historical background and encourage reflection. For that to work, it’s important to take a clear stand against all political attempts to exert influence or co-opt the museum; this is the only way the museum can remain a forum that is open to everyone.

Hetty Berg, thank you very much for the interview!

The interview was conducted by Marie Naumann and Katharina Wulffius.

This interview was first published in 2020 in issue 21 of the print edition of the JMB Journal.

Citation recommendation:

Marie Naumann, Katharina Wulffius (2020), Lucky Coincidences. Interview with our New Museum Director Hetty Berg.

URL: www.jmberlin.de/en/node/6917