On International and Other Remembrance Days

On 27 January 1945, the Soviet Army liberated the death camps Auschwitz I and II. In 2005, the anniversary was designated International Holocaust Remembrance Day. Although I’ve been reflecting on representations of the Holocaust in art, literature, and philosophy for many years, I remain irritatingly little affected by this date, January 27.

Surviving children in the main concentration camp, Auschwitz. This still from documentary footage shot by Alexander Voronzow shows Tomasz Szwarz, Alicja Gruenbaum, Solomon Rozalin, Gita Sztrauss, Wiera Sadler, Marta Wiess, Boro Eksztein, Josef Rozenwaser, Rafael Szlezinger, Gabriel Nejman, Gugiel Appelbaum, Mark Berkowitz, Pesa Balter, Rut Muszkies, Miriam Friedman, and Miriam and Eva Mozes. Licensed for the public domain by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

In most European countries, official events collectively recall that breach of civilization and commemorate those who were systematically murdered. So too in Germany. Here, the decision to officially commemorate the victims of the Holocaust on this day was reached in 1996—not least because the fall of the Berlin Wall on November 9, 1989, threatened to overshadow the other watershed events in twentieth-century German history that took place on the same date: the November Revolution of 1918, the Hitler putsch of 1923 and, notably, the “Kristallnacht” of 1938. By contrast, the date of January 27 had never played a prominent role in the post-war remembrance culture of West Germany. Which is perhaps why this anniversary still doesn’t really touch my heart.

Auschwitz became synonymous for the systematic murder of European Jews even before the Cold War had ended. This was due not so much to the photos taken by Soviet soldiers of the prisoners in the camps after liberation as to those taken by the SS of deportees on the ramps at Auschwitz-Birkenau.

Literary accounts of the latter, such as Primo Levi’s Survival in Auschwitz (written in 1945–47 and published in 1958) or Jean Améry’s autobiographical collection of essays At the Mind’s Limit (1966), and the first Auschwitz trial in Frankfurt (1963–65) cemented the pivotal role played by Auschwitz in collective consciousness.

Unlike abstract terms such as “Holocaust,” “Shoah,” and “genocide,” the word Auschwitz, as Adorno noted, represented a concrete place and the inconceivable extermination of human beings and the erasure of their names. It is only logical that the day when Auschwitz ceased to be a death camp was seized as an opportunity to commemorate the nameless that were murdered here.

A photo from the so-called “Auschwitz Album” that was used as evidence in the Auschwitz Trial, inter alia. An SS officer, (presumably either Ernst Hofmann or Bernhard Walter) took this photo of Hungarian Jews’ arrival at Auschwitz-Birkenau in late May or early June 1944. Those pictured here awaiting so-called “selection” on the ramps have not yet been identified. CC-BY-SA 3.0 Bundesarchiv (German Federal Archives).

A photo from the so-called “Auschwitz Album” that was used as evidence in the Auschwitz Trial, inter alia. An SS officer, (presumably either Ernst Hofmann or Bernhard Walter) took this photo of Hungarian Jews’ arrival at Auschwitz-Birkenau in late May or early June 1944. Those pictured here awaiting so-called “selection” on the ramps have not yet been identified. CC-BY-SA 3.0 Bundesarchiv (German Federal Archives).

But the importance of Auschwitz in today’s memory of the Holocaust does not account for the UN General Assembly’s designation of January 27 as International Holocaust Remembrance Day alone, for the day also marks the implementation of a resolution taken in the year 2000 by Stockholm’s “International Forum on the Holocaust.” The Remembrance Day illustrates the so-called “universalization of the Holocaust,” echoed in Jan Eckel and Claudia Moisel rightful claim that

“no other historical event has come anywhere near attaining such broad international significance.”

On January 27, collective memory in Germany becomes part of this global act of commemoration. The homeland of the perpetrators and their descendants now remembers its systematic mass murder on the same day as countries such as the Czech Republic and Greece do—countries that were once under German occupation.

Footage of the Ayalon highway in Tel Aviv, taken while the sirens wail for Yom ha-Shoah, video: Hanok Dakar

In Israel, by contrast, another day is of major importance. There, they commemorate the extermination of European Jews on the 27th day of the Jewish calendar month Nissan by bringing public life to a standstill for two minutes.

Before this haunting form of collective commemoration on Yom ha-Shoah was introduced, practicing Jews, particularly those in the US, used to commemorate the Holocaust on the ninth day of the month of Av, which is Tisha b’Av, the day of fasting that recalls the Destruction of the Temple. Rabbi Manuel Saltzman once described the connection between these two events with the words,

“Jews [all over] the world gather in synagogues on the holiday of Tisha b’Av [Ninth of Av] to commemorate the great calamities which befell our people in our past history and culminat[ed] in the tragic extermination of six million Jews in our day. We [will] never forget these martyrs and [pray] that all mankind will remember them.“ (Cited in: Hasia R. Diner, We Remember with Reverence and Love)

Only those who allow themselves to be moved by an event can commemorate it; only those who are really touched will remember. The act demands a framework that may indeed be collective in character, but doesn’t necessarily have to be. The collective that commemorates the Holocaust and its victims on January 27 is less universal than its international framework suggests—the day that reminds me of Auschwitz is different.

Mirjam Wenzel, Media

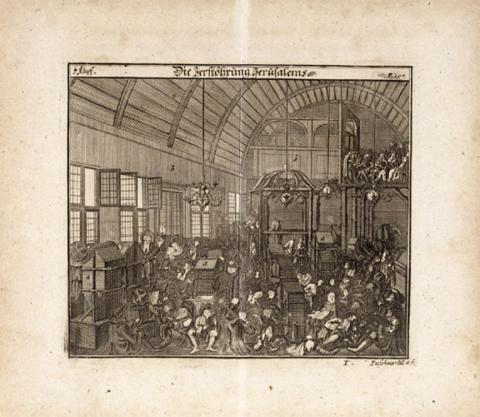

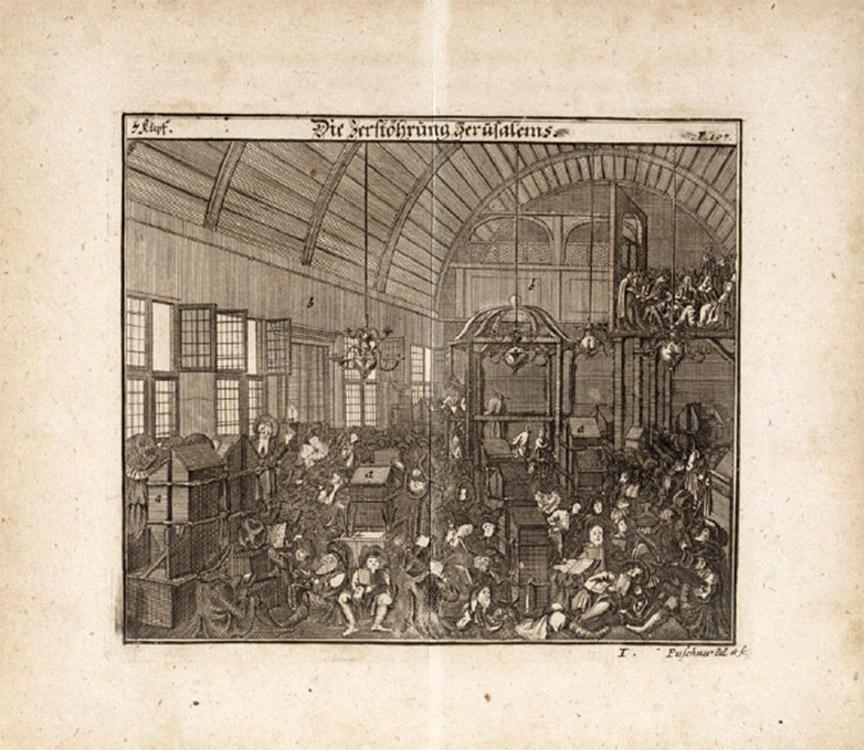

Joh. Georg Puschner Die Zerstöhrung Jerusalems (The Destruction of Jerusalem), here reproduced in: Paul Christian Kirchner, Jüdisches Ceremoniel, copperplate on cotton paper, Peter Conrad Monath, Nuremberg 1734; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession GDR 78/7/0, photo: Jens Ziehe. For further details see our collections online (in German).

Joh. Georg Puschner Die Zerstöhrung Jerusalems (The Destruction of Jerusalem), here reproduced in: Paul Christian Kirchner, Jüdisches Ceremoniel, copperplate on cotton paper, Peter Conrad Monath, Nuremberg 1734; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession GDR 78/7/0, photo: Jens Ziehe. For further details see our collections online (in German).

Citation recommendation:

Mirjam Wenzel (2015), On International and Other Remembrance Days.

URL: www.jmberlin.de/en/node/7703