Hebrew Printing in Berlin

Collection at Our Library

Our collection on Hebrew printing in Berlin was largely acquired from 1999 to 2002 through the Amsterdam antiquarian Willem Burgers (1929–2013). It includes 150 titles from the eighteenth century and 100 titles from the nineteenth century, along with about 100 Hebrew and 50 Yiddish titles from the period 1900 to 1933.

Where

W. M. Blumenthal Academy, Library

Fromet-und-Moses-Mendelssohn-Platz 1, 10969 Berlin

Postal address: Lindenstraße 9-14, 10969 Berlin

The Beginnings of Hebrew Printing in Berlin

Hebrew printing in Berlin, which commenced later than in other German cities, started on the initiative of the Christian Hebraist and Prussian court preacher Daniel Ernst Jablonski (1660–1741), who published a Hebrew Bible in 1699, and later also financed an edition of the Babylonian Talmud. He engaged the Jewish scholar Jehuda Löb ben David Neumark from Hanau as advisor and printer. Zeev Wolf ben Salman Mirels, Baruch Buchbinder and Neumark’s son Natan Neumark were soon operating their own printing presses, where they mostly published texts and commentaries on religious law. Aharon ben Moshe Rofe and Itzig Speier continued this tradition into the 1760s.

Heyday during the Jewish Enlightenment

Berlin became a center of Hebrew printing during the Haskalah, otherwise known as the Jewish Enlightenment. Its exponents – maskilim such as Naphtali Herz Wessely (1725–1805), who oriented themselves on reason, philosophy and scholarship – rocked the authority of the Rabbinical elite with their works written in Hebrew, and introduced secular knowledge into the religious tradition. Moses Mendelssohn (1729–1786) translated the Torah into German, but from 1780 to 1783 had it printed using the Hebrew alphabet to introduce Yiddish-speaking Jews to the German language, and to enable them to form their own opinions on the Book of Books.

X

X

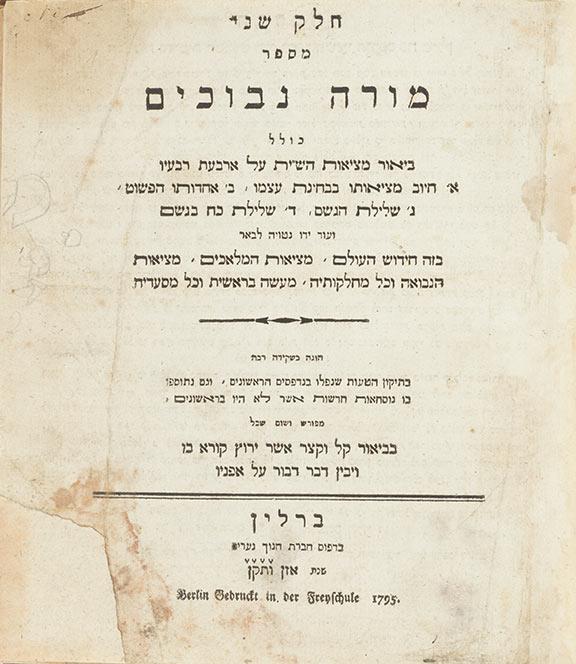

Title leaf of the second volume of Sefer moreh nevukhim (Guide for the Perplexed) by Moses Maimonides with the German imprint “Berlin Gedruckt in der Freyschule 1795” (Berlin printed in the Free School 1795); Jewish Museum Berlin, VII.5. Maimo 252 Vol.2, photo: Roman März

Founded in 1778, the Jüdische Freyschule (Jewish Free School), which implemented the Haskalah's educational reforms, received the license to print books in oriental languages in 1784, which helped finance the school. Under the direction of Isaak Satanow (1732–1805) and Isaak Euchel (1756–1804), the Orientalische Buchdruckerey (Oriental Printing Press), named after the license, published most of the works of the Haskala, including for a time the periodical Ha-me'assef (The Collector), but also school books and the Calender für die Jüdische Gemeinde (Calender for the Jewish Community), which, after the closure of the Free School and its printing press in 1825, continued to be published for a few decades in Hebrew and later in German using the Hebrew alphabet.

Diversification in the Nineteenth Century

As Jewish citizens began to achieve social equality in the nineteenth century, Hebrew lost its function as the language of scholarship, writing and the vernacular. Hebrew book culture was diversified through source editions and textbooks for schools and universities, as well as through religious functional literature for the home and synagogue. Prayer books were now printed bilingually, but the pages were still turned from left to right. Countless printing houses, such as Lewent, Kornegg, Sittenfeld and Itzkowski supplied the Hebrew book market. Towards the end of the century, in the context of Zionism, the periodical Ha-shiloah, edited by Achad Ha'am (1856–1927) and initially published in Berlin, began to modernize Hebrew language and literature.

Collection Title List (in German)

Download (PDF / 5.85 MB / in German / not accessible)After the First World War

Hebrew printing in Berlin experienced another brief blossoming after the First World War, when Eastern European publishers, attracted by the post-war inflation and infrastructure, printed mainly Yiddish works and founded artistically sophisticated publishing houses, such as the Rimon-Verlag and the Klal-Verlag. The Soncino-Gesellschaft der Freunde des jüdischen Buches (Soncino Society of Friends of the Jewish Book), founded in 1924, initiated a new typeface; their edition of the Torah, completed in 1933, marked a highpoint of Hebrew printing in Berlin at the time.

Digitization

A selection of 65 volumes from this collection was digitized in 2022. We received support for this project from the interdisciplinary Service Center for Digitization Berlin (digiS), as part of the funding project for the digitization of cultural heritage assets in Berlin. View publications on the OPAC library catalog (in German)

References

- Bendt, Vera, “Willem Burgers Ein Amsterdamer Antiquar im Geiste von Spinoza.” In: Imprimatur N.F. 24.2015, 11–54.

- Brenner, Michael, ed. Jüdische Sprachen in deutscher Umwelt. Hebräisch und Jiddisch von der Aufklärung bis ins 20. Jahrhundert. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht, 2002.

- Feiner, Shmuel, The Jewish Enlightenment. Trans. from the Hebrew by Chaya Naor. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004.

- Leicht, Reimund, “Daniel Ernst Jablonski und die Drucklegungen des Babylonischen Talmud in Frankfurt/Oder und Berlin (1697–1699, 1715–1722, 1734–1739).” In: Joachim Bahlcke and Werner Korthaase, eds. Daniel Ernst Jablonski. Religion, Wissenschaft und Politik um 1700. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2008, 491–516.

- Meisl, Josef, “Berliner jüdische Kalender.” In: Soncino-Blätter 2.1927, 41–54. – Online: http://sammlungen.ub.uni-frankfurt.de/cm/periodical/pageview/3983921

- Steinschneider, Moritz and David Cassel, “Jüdische Typographie und jüdischer Buchhandel.” In: Johann S. Ersch and Johann G. Gruber, Allgemeinde Encyclopädie der Wissenschaften und Künste. 2. Sect., 28 T. Leipzig: Brockhaus, 1851, 21–94, esp. 89–91. – Online: http://resolver.sub.uni-goettingen.de/purl?PPN362307695

Can I borrow books from the library?

We do not lend books. Our holdings can only be viewed in the Reading Room.

How can I conduct research using the museum’s archive, collections, and library?

Our Reading Room is open to the public. You can also research using our library’s holdings and some of our collection’s holdings online. To view additional holdings, please contact the responsible curators.

I would like to depict or borrow an object from your collections. Who should I contact?

Your contacts for photo permissions are Valeska Wolfgram and Birgit Maurer-Porat (T +49 (0)30 259 93 433, email: fotodoku@jmberlin.de). Loan requests must be made at least six months in advance. For questions regarding administrative processes, please contact Katrin Strube (T +49 (0)30 259 93 417, email: k.strube@jmberlin.de).

Special Collections: On Jewish Art and Culture (6)