„Es war schon mehr eine Treibjagd!“

Max Karp über seine Deportation aus Berlin am 28. Oktober 1938

„Am 28.10. wurden wir in Berlin ab 6 Uhr früh aus den Betten heraus von der Polizei verhaftet und in der Kaserne Kl. Alexanderstr. aus den Bezirken Bln-Mitte, Norden & Tiergarten zum Abtransport gesammelt.“

So beginnt der lange Bericht von Mendel Max Karp über seine Deportation aus der deutschen Hauptstadt am 28. Oktober 1938.

Niedergeschrieben hat er ihn am 17. November 1938 in dem polnischen Grenzort Zbąszyń in einem Brief an seinen Neffen Gerhard Intrator, der seit 1937 in New York wohnte. Darin schildert der 1892 in dem Dorf Ruszelczyce nahe Przemyśl geborene Musiker in erschütternder Weise den genauen Verlauf seiner Verhaftung und Abschiebung.

Max Karp war einer der ca. 17.000 polnischen Staatsangehörigen, die im Rahmen der sogenannten Polenaktion vom 27. bis zum 29. Oktober 1938 aus Deutschland ausgewiesen wurden. Seine Darstellung der Ereignisse zählt zu den frühesten überhaupt und ist in ihrer Detailliertheit und in ihrem Umfang unübertroffen. Wir geben den Bericht über seine Erlebnisse am 28. und 29. Oktober in vollem Wortlaut wieder:

„In Berlin wurden nur Männer im Alter von 15-ca. 90 Jahren von dieser Aktion betroffen. Die Polizeibeamten überreichten uns ein Formular in der Wohnung, worauf stand, daß wir das Reichsgebiet binnen 24 Stunden zu verlassen haben. Diese Frist wurde uns nicht gegeben und [wir] mußten den Beamten folgen, sobald wir angezogen waren und kaum Zeit mehr übrig blieb Kleidung und Wäsche etc. mitzunehmen. Nur dürftig bekleidet und mit nur ein paar Mark habe ich Deutschland verlassen müssen.In anderen Städten und Provinzen des Reichsgebiets wurden die gesamten jüdischen Familien, die dort lebten, am Donnerstag Abend d. 27.10. verhaftet und über Nacht in Zellen gesperrt, wo man keine Rücksicht auf Säuglinge, Kinder, Schwangere und Greise noch auf Erkrankte nahm. Das Letztere traf auch auf Berlin zu.

Nachdem die Sammelaktion in Berlin durchgeführt war, wurden wir in halb geschlossenen oder etwas verdeckten Lastautos und unter Bewachung von der Polizeikaserne nach einem Güterbahnhof in Treptow nahe Neukölln gebracht. Vor der Kaserne und in den angrenzenden Straßen spielten sich ergreifende Szenen der in Berlin zurückgebliebenen Frauen, Mütter & Kinder ab.

X

X

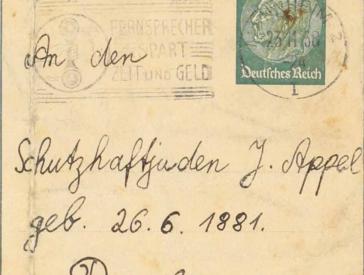

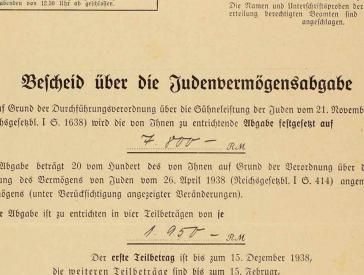

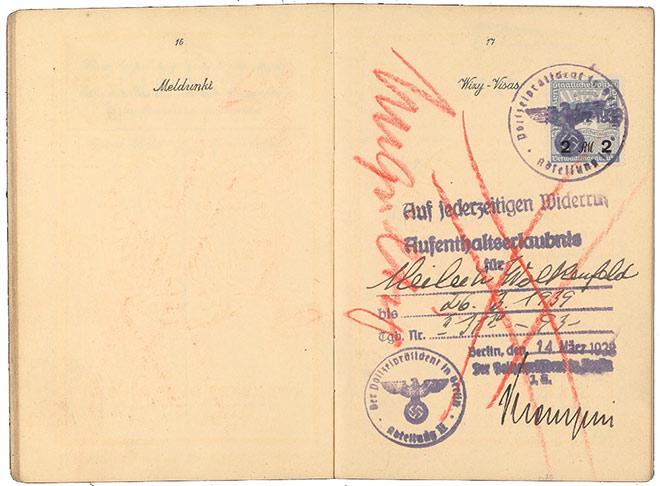

Aufforderung an Meilech Wolkenfeld, das Reichsgebiet innerhalb von 24 Stunden zu verlassen. Das Schreiben wurde ihm am 28. Oktober 1938 in Berlin vorgelegt, er wurde jedoch gleich verhaftet und wie Max Karp an die polnische Grenze deportiert; Jüdisches Museum Berlin, Schenkung von Jack Wolkenfeld

Ein Auto nach dem anderen verließ mit uns den Kasernenhof, ein lange Kette dieser Monsterwagen schlängelte sich über den ›Alex‹ weiter durch die Stadt unter ungeheurem Sirenenlärm der Autos, der wohl absichtlich gemacht wurde, um die Bevölkerung Berlins auf unsern zwangsweisen Abtransport aufmerksam zu machen. Die Menschen stauten sich in den Straßen, sie sollten Zeugen sein der ›historischen‹ Austreibung von Juden aus Deutschland.An den Bahngleisen in Treptow angekommen, verließen wir die Autos, die nachträglich bemerkt, keine Bänke zum Sitzen hatten, und wir tüchtig durcheinander gerüttelt waren. Wir sind froh gewesen, wieder auf festem Boden zu stehen.

Vor Besteigung der Züge wurden wir in Gruppen eingeteilt und mussten dann unsere Pässe abgeben, währenddessen stand vor uns aufmarschiert eine Kompagnie Schupos, die gerade ihre Gewehre ladeten, was uns wohl absichtlich gezeigt werden sollte.

Diese Mannschaften begleiteten uns während der Fahrt, außerdem Gestapo und Ausländerpolizei. Wir fuhren in 8 Zügen, das einzig angenehme an der Sache. Die Reise ging über die Treptow-Stralauer Eisenbahnbrücke, dann rechts im Bogen heraus und später über Frankfurt O. nach der Grenze zu.

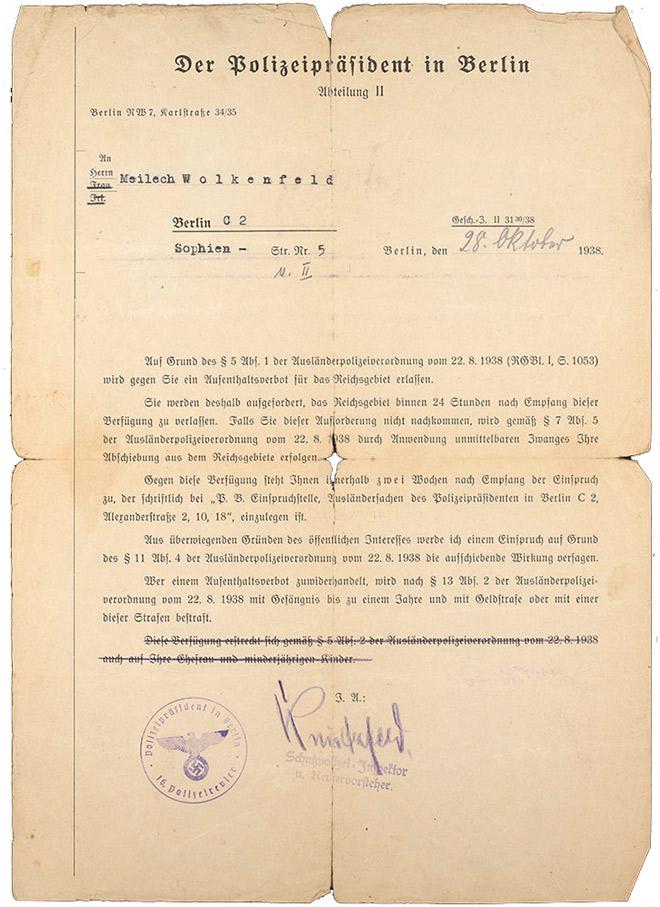

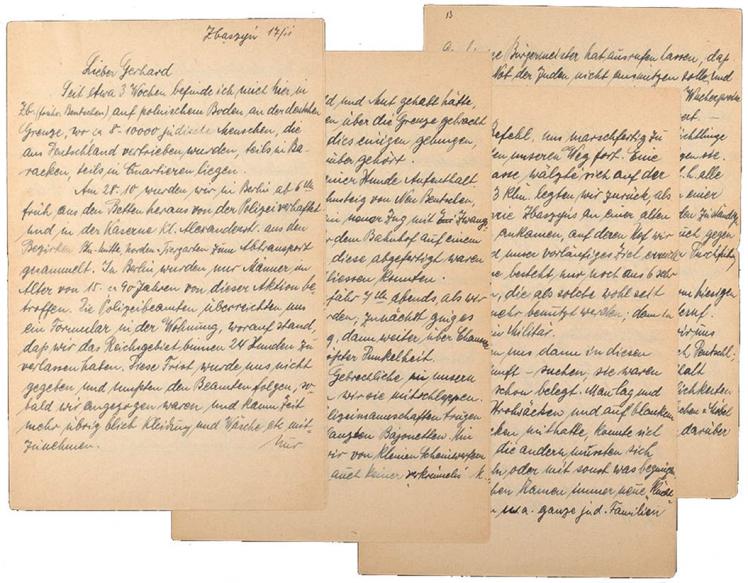

Die erste Seite von Mendel Max Karps Brief aus Zbąszyń vom 17. Dezember 1938; Jüdisches Museum Berlin, Schenkung von Joanne Intrator. Weitere Informationen zu diesem Dokument finden Sie in unseren Online-Sammlungen

X

X

Die erste Seite von Mendel Max Karps Brief aus Zbąszyń vom 17. Dezember 1938; Jüdisches Museum Berlin, Schenkung von Joanne Intrator. Weitere Informationen zu diesem Dokument finden Sie in unseren Online-Sammlungen

In Neu Bentschen mussten wir aussteigen, und jede Gruppe vor ihrem Wagen zunächst stehen bleiben. Dort wurden wir namentlich aufgerufen und bekamen dann unsere Pässe, in denen das deutsche Aufenthaltsvisum ungültig gemacht worden war, wieder ausgehändigt. Auf dem Bahnsteig mußten wir noch eine Weile verbleiben, bis die Zoll und Devisenkontrolle, die sehr oberflächlich und schnell wegen der weiter einlaufenden Transporte, durchgeführt wurde, vorüber war. Wer Geld und Mut gehabt hatte, der konnte ein Vermögen über die Grenze gebracht haben. Vielleicht ist dies einigen gelungen, ich habe so etwas darüber gehört.Nach etwa einer Stunde Aufenthalt verliessen wir den Bahnsteig von Neu Bentschen, währenddessen lief ein neuer Zug mit Zwangsemigrierten ein. Vor dem Bahnhof auf einem Platz warteten wir, bis diese abgefertigt waren und sich uns anschliessen konnten.

Es war ungefähr 7 Uhr abends, als wir in Marsch gesetzt wurden; zunächst ging es an der Bahn entlang, dann weiter über Chaussee und Feldwege bei größter Dunkelheit.

Da wir einige Gebrechliche in unsern Reihen hatten, mussten wir sie mitschleppen. Die uns begleitenden Polizeimannschaften trugen Gewehre mit aufgepflanzten Bajonetten. Hin und wieder wurden wir von kleinen Scheinwerfern beleuchtet, damit sich auch keiner verkrümeln konnte. Ein bestimmtes Marschtempo mußte von uns eingehalten werden, es war schon mehr eine Treibjagd! Wer nicht mithalten konnte, wurde mit schmerzhaften Schlägen und Rippenstößen vorwärts getrieben.

Verschiedene unter uns hatten von Hause aus in aller Eile noch Gepäck mitnehmen können, das wir abwechselnd trugen. Doch einem und jedem andern von uns war es nicht möglich seinen Koffer, der für mehrere tausend Mark Pelze enthielt und sehr schwer war, bei diesem Eiltempo nur auf kurze Dauer zu tragen, sodaß er auf der Strecke bleiben musste. Die Beamten nahmen auch auf diesen Fall keine Rücksicht und bekamen wir oft genug von ihnen höhnische Zurufe zu hören.

X

X

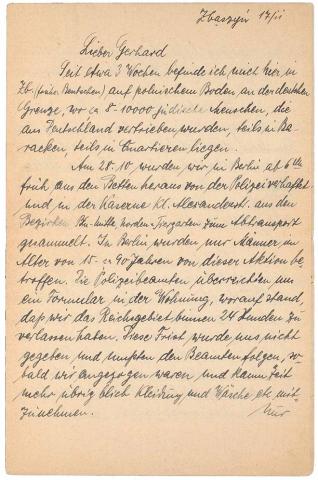

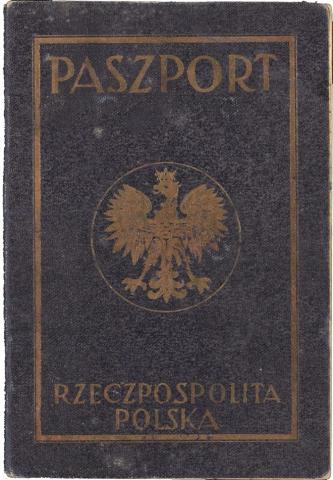

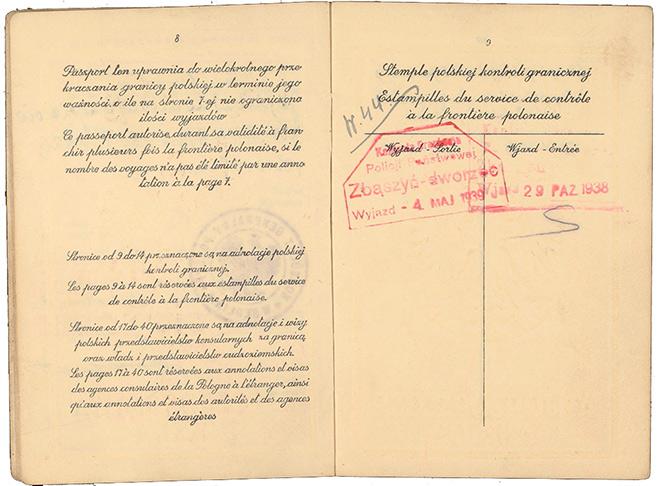

Pass von Meilech Wolkenfeld, dessen Aufenthaltsgenehmigung am 28. Oktober 1938 ungültig gemacht wurde; Jüdisches Museum Berlin, Schenkung von Jack Wolkenfeld

Nachdem wir ungefähr 7 klm marschiert waren, mussten wir plötzlich mäuschen still sein. Die Polizeimannschaften zogen sich allmählich zurück oder einzelne Beamte blieben stehen, während wir langsam weitermarschieren mußten. Nun merkten wir, daß wir über die grüne Grenze geschoben wurden. Wir passierten zunächst einen Grenzschlagbaum, bewegten uns auf Niemandsland, um dann etwas weiter einen zweiten Schlagbaum zu passieren, der uns nach seinen Farben in der Dunkelheit schwach anzeigte, daß wir jetzt auf polnisches Gebiet hinübergehen.Unweit der Grenze machten wir vor einem polnischen Grenzhäuschen halt, während das Ende des Zuges sich noch auf Niemandsland befand. Zwei Grenzpolizisten traten aus ihrem Häuschen und waren erstaunt, eine kaum übersehbare Menschenmenge vor sich zu haben. Wir mussten nun einige hundert Meter weiter marschieren, bis sich der ganze Flüchtlingsstrom auf polnischem Gebiet befand.

Wir standen auf einer schnurgeraden Chaussee am Waldesrand. Gott sei Dank war das Wetter milde. Gegen ½ 10 Uhr abends wurden auf der Chaussee bei Scheinwerferlicht unsere Pässe kontrolliert. Nachdem dies beendet war, mussten wir die Nacht über an Ort und Stelle verbleiben. Diejenigen, die Koffer mithatten, konnten darauf sitzen. Es waren nur wenige; wir andern standen bis zum Morgengrauen, hin und wieder hatte es auch geregnet. Die ganz alten Männer über 70 wurden von Neu Bentschen in Postautos an die Grenze gebracht und wurden sie zur gleichen Zeit wie wir abgeliefert, die meisten von ihnen bekamen über Nacht Sitzgelegenheit im Grenzhaus.

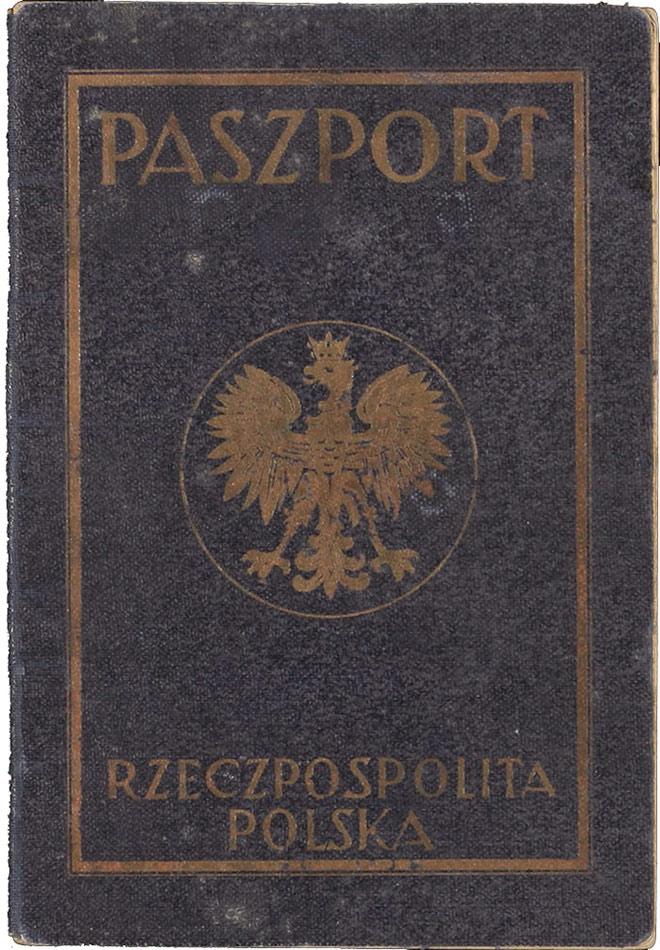

Pass von Meilech Wolkenfeld; Jüdisches Museum Berlin, Schenkung von Jack Wolkenfeld. Weitere Informationen zur Sammlung Familie Wolkenfeld finden Sie in unseren Online-Sammlungen

X

X

Pass von Meilech Wolkenfeld; Jüdisches Museum Berlin, Schenkung von Jack Wolkenfeld. Weitere Informationen zur Sammlung Familie Wolkenfeld finden Sie in unseren Online-Sammlungen

Aus Zbąszyń trafen im Laufe des Abends Polizisten bei uns ein, die Wache hielten. Früh um 6 Uhr, als der Morgen graute, hielten wir von diesen Befehl, uns marschfertig zu machen und setzten unseren Weg fort. Eine müde Menschenmasse wälzte sich auf der Chaussee. Etwa 3 klm legten wir zurück, als wir an der Peripherie Zbąszyń an einer alten Kavalleriekaserne ankamen, auf deren Hof wir Halt machten und unser vorläufiges Ziel erreicht hatten. Die Kaserne besteht nur noch aus 6 sehr großen Stallungen, die als solche wohl seit langem nicht mehr benutzt werden; denn in diesem Ort liegt kein Militär.Wir konnten uns dann in diesen Gebäuden Unterkunft suchen; sie waren zu großen Teil schon belegt. Man lag und schlief dort auf Strohsäcken und auf blankem Stroh. Nur wer Decken mithatte, konnte sich warm einhüllen; die anderen mussten sich mit ihren Mänteln oder mit sonst was begnügen.

Inzwischen kamen immer neue ›Flüchtlinge‹ (aus D. Vertriebene) an u.a. ganze jüd. Familien aus verschiedenen Provinzen Deutschlands, die man mit Sack und Pack auf Bauernwagen von der Grenze abgeholt hatte. Das Bild, das sich da bot, machte herzerschütternd und vielen standen die Tränen in den Augen.

Das Gedränge auf dem Kasernenhof und in den Baracken wurde immer stärker. Überall wo man hinsah, verzweifelte und weinende Menschen; zwischendurch erblickte man auch betende Juden in Tallis & Twillen an einzelnen Bäumen stehend und in den Baracken.

Fast den ganzen ersten Tag irrte ich unter schwerster seelischer Depression umher; ich fand nirgends Ruhe. Das Flüchtlingslager, das polizeilich bewacht war, durfte zunächst keiner verlassen; erst am 3. Tage nachdem unsere gesamten Pässe kontrolliert worden waren, wurden die Pforten wieder geöffnet und allmählich gewannen wir unsere Freiheit wieder zurück.“

X

X

Zbąszyń Eingangs- und Abgangsstempel im Pass von Meilech Wolkenfeld; Jüdisches Museum Berlin, Schenkung von Jack Wolkenfeld

Einige Seiten von Mendel Max Karps Brief aus Zbąszyń vom 17. Dezember 1938; Jüdisches Museum Berlin, Schenkung von Joanne Intrator

In der Fortsetzung seines Briefes beschreibt Max Karp die schweren Folgen der Deportation für zahlreiche Vertriebene: Tod, Selbstmord, Ohnmacht, Wahn und schwere Erkrankungen. Er schildert die allmählich anlaufenden Hilfsaktionen, die Ankunft von Ärzt*innen und weiterem medizinischen Personal aus Warschau, die Verteilung von Lebensmitteln und Bekleidung, die Unterstützung durch den Bürgermeister von Zbąszyń und die Hilfeleistungen einiger christlicher Familien. Die verbreitete Hoffnung auf eine baldige Rückkehr nach Deutschland wurde aber durch den „Schuß in Paris“, das Attentat auf den Diplomaten Ernst vom Rath am 7. November 1938, zunichte gemacht.

Max Karp musste insgesamt acht Monate in Zbąszyń ausharren. Erst Ende Juni 1939 konnte er nach Berlin zurückkehren, um seine Emigration endgültig zu organisieren. „Ich möchte schnellstens von hier fort, da die Lage sehr gespannt ist“, schrieb er an seinen Neffen Gerhard am 8. August. Zwei Wochen später schien er alle notwendigen Papiere beisammen zu haben, um nach Shanghai auszuwandern. Der deutsche Überfall auf Polen und Beginn des Zweiten Weltkriegs vereitelten jedoch seine Pläne. Am 13. September 1939 wurde Max Karp im Rahmen der zweiten „Polenaktion“ erneut verhaftet, in das Konzentrationslager Sachsenhausen gebracht und dort am 27. Januar 1940 ermordet.

Aubrey Pomerance, Archivleiter, hat in den letzten Jahren einzelne Personen kennengelernt, die Ende Oktober 1938 nach Zbąszyń deportiert wurden.

Zitierempfehlung:

Aubrey Pomerance (2018), „Es war schon mehr eine Treibjagd!“. Max Karp über seine Deportation aus Berlin am 28. Oktober 1938.

URL: www.jmberlin.de/node/6557

Online-Features: Zur Vorgeschichte und den Folgen des 9. November 1938 (5)

X

X