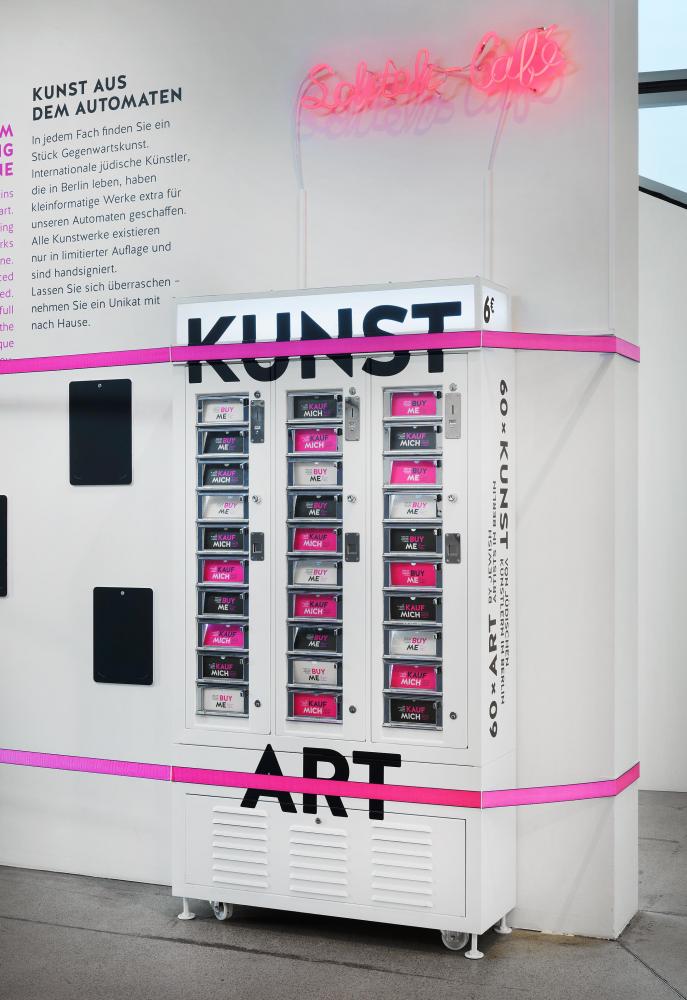

Art Vending Machine

2013–2018

High quality photo prints, printed textiles, and small sculptures – the art vending machine, at the Jewish Museum Berlin from August 2013 to June 2018, offered a wide range of surprising contemporary art hiding in its 30 compartments. The small-format unicums were created by international Jewish artists living in Berlin. All works of art were made exclusively for the art vending machine and are hand signed limited editions. Once they were sold, they were gone.

Where

Libeskind Building, ground level, Eric F. Ross Gallery

Lindenstraße 9–14, 10969 Berlin

Contemporary Art for 6 Euros

Visitors were able to draw a piece of contemporary art from the machine – a redesigned and rebuilt vending machine from the 1970s – for 6 €, payable in three two-€ coins.

Artists and Artworks

The following artists were involved in the project:

X

X

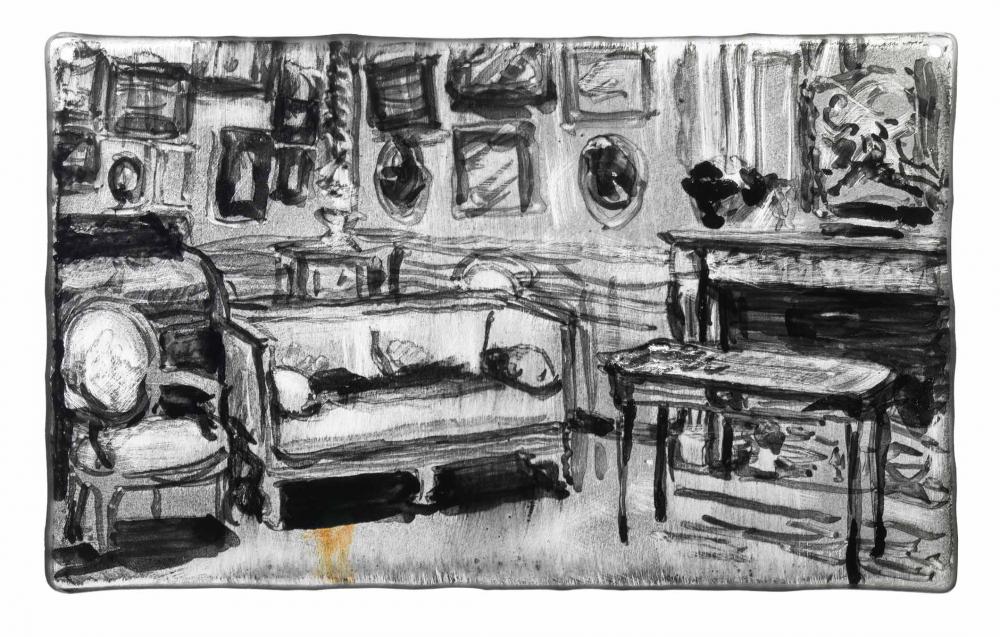

The art vending machine in the previous permanent exhibition; Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Jens Ziehe

April–December 2016

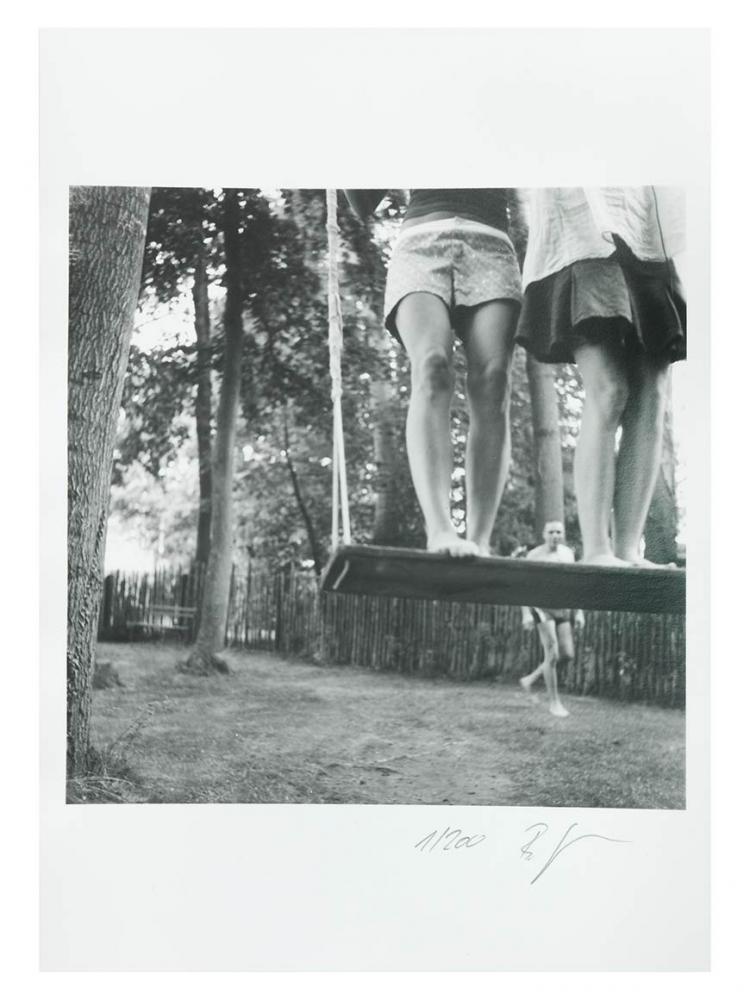

Birgit Naomi Glatzel (born in Kempten, Germany, 1970), Angela and Me, photo project You and Me; Jewish Museum Berlin,

Friends Sixteen Times Removed and a Camel on a World Tour

It’s a warm day of the summer 2016 when I visit Birgit Glatzel in Prenzlauer Berg, the same kind of day it must have been when she shot her photograph Angela and Me, which, like her short film Going to Jerusalem, was available in our art vending machine.

Angela and Birgit

Angela and Me is part of a series in which the artist portrays herself with a friend in self-timed pictures. All the photographs are taken with a 1937 Rolleiflex camera, and the location and backdrop are always chosen together with the friend in question. Birgit embarked upon the project shortly before her emigration to Israel in 2007 – she wanted to take photos to remember her friends in Germany. “Memories play an important role in Judaism, for example an original piece is always left in a newly refurbished apartment,

” explained the artist, who trained as an architect and works as such to earn her living.

Before I talk to Birgit about her art, she shows me the studio where she works and has lived with her son since her return to Berlin. I love the sliding walls that can hide the bathroom of the large studio apartment. Then Birgit tells me that Angela and Me shows her with her friend Angela, whose birthday they were celebrating at the Müggelsee in the summer of 2014. However, only the legs of the two women standing on a swing are shown, and upon closer inspection, a man in the background looking directly into the camera.

“Does it bother you that somebody just walked into your picture?

” I ask Birgit. No, he is part of the picture because he shows the elements of chance and of surprise that can result from the self-timer delay. “I knew the moment the photo was taken that it would turn out like this.

” “And how do you feel about your private souvenir photo hanging in other people’s homes?

” “I love this uncontrollable dispersal of my art. And since our faces are not visible, it is anonymous enough as well.

” There is already a waiting list for the photo series – other friends want to be part of the project.

Jerusalem in the Fridge

Birgit Glatzel also enjoys working with a partner on other projects because it inspires the best ideas. That was how it was with the art film Going to Jerusalem that she made with the animation filmmaker Benjamin Seide. It evolved ten years ago as a contribution for an exhibition in Jerusalem on the theme of “Land(e)scaping.” Benjamin and Birgit wanted to address the complex, five-thousand-year history of Jerusalem in an entertaining way, without ridiculing it.

The idea was sparked by a snow globe containing the Jerusalem skyline and a camel that Birgit had been given by a friend, Hagar from Israel – the two of them decided to “liberate” the city skyline from its ball and send it on a world tour accompanied by the camel. So they destroyed the snowball and used both as “leading actors” for her film. Filming locations included the icebox of Birgit’s fridge and the playground opposite her apartment. “Oddly enough, no one in Israel laughed at the film although it is so absurd – for example you see the camel hanging in a cable car over the Alps,

” wonders Birgit. “Your colleague Gelia Eisert was the first to find the film funny.

” “I also had a good laugh,

” I can reassure Birgit.

Since there was only one more public showing of the film in Jerusalem after the exhibition, Birgit has ensured its survival by putting it on a USB stick for our art vending machine. The stick was stuck on a postcard showing the camel in the cable car and the card is lovingly hand-stamped with camel heads designed by Benjamin Seide and Birgit Glatzel. “Working with Benjamin was great fun,

” laughs Birgit. “It was a charming and very special collaboration during the film production and, many years later, designing the card. Unfortunately, this was our only joint project so far.

”

A Friend is a Friend of a Friend

Still of particular importance to Birgit Glatzel is her first major long-term project, which again unites the two motifs from the other works of art – friendship and travel. This was the first project she used the Rolleiflex for – her camera for special occasions, as one photo costs about 2 euros, so you think twice before pressing the shutter. For A Friend is a Friend of a Friend, Birgit sent herself off traveling for four years and visited first friends around the world, then friends of those friends and so on – a total of 340 people, some of whom were friends 16 times removed. “I wanted to show that it’s possible to do it differently and that the Internet does not replace personal experience.

”

Birgit Glatzel took a picture with her Rolleiflex of all the friends and friends of friends she met and with whom she sometimes stayed. The camera was always a good place to start at a first meeting with what were mostly strangers – “It is is an element that we all know and at the same time you can take photos inconspicuously with it, so it is not so intimidating.

” The Rolleiflex was a chance discovery – “I had always wanted a camera like that and came across it when I was looking for a flash for a different camera.

” The photo project led to an exhibition and many years later to a book that Birgit Glatzel financed through a several-month crowdfunding campaign. It shows very many very different people from all around the world in their private environments. The appendix has a list of everyone depicted, listed by place of residence, occupation, or “friendship clan,” to quote Birgit.

Birgit invites me to look through the Rolleiflex at the end. “You see everything back to front,

” says Birgit “but I don’t even notice that anymore.

” She also gives me a signed copy of A Friend is a Friend of a Friend, number 184 of 300, as a reminder of our afternoon together at her studio, which has flown by. The book now has its place on my desk and reminds me that you should send yourself off traveling more often or visit friends or people who you don’t know (yet).

Mariette Franz, Digital & Publishing

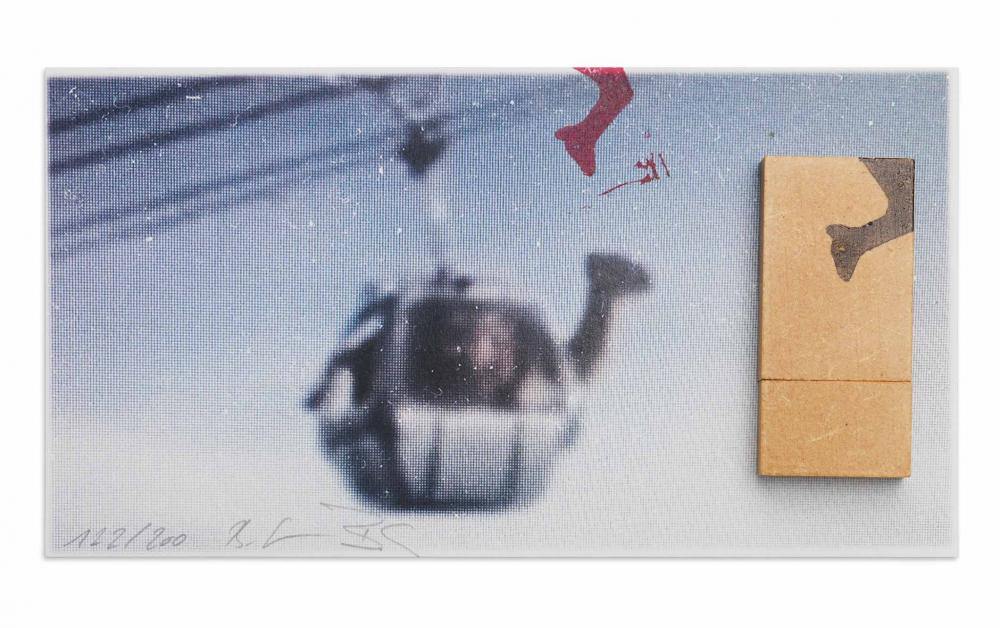

Birgit Naomi Glatzel (born in Kempten, Germany, 1970) & Benjamin Seide (born in Frankfurt Main, Germany, 1968), Going to Jerusalem: Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Jens Ziehe.

Friends Sixteen Times Removed and a Camel on a World Tour

It’s a warm day of the summer 2016 when I visit Birgit Glatzel in Prenzlauer Berg, the same kind of day it must have been when she shot her photograph Angela and Me, which, like her short film Going to Jerusalem, was available in our art vending machine.

Angela and Birgit

Angela and Me is part of a series in which the artist portrays herself with a friend in self-timed pictures. All the photographs are taken with a 1937 Rolleiflex camera, and the location and backdrop are always chosen together with the friend in question. Birgit embarked upon the project shortly before her emigration to Israel in 2007 – she wanted to take photos to remember her friends in Germany. “Memories play an important role in Judaism, for example an original piece is always left in a newly refurbished apartment,

” explained the artist, who trained as an architect and works as such to earn her living.

Before I talk to Birgit about her art, she shows me the studio where she works and has lived with her son since her return to Berlin. I love the sliding walls that can hide the bathroom of the large studio apartment. Then Birgit tells me that Angela and Me shows her with her friend Angela, whose birthday they were celebrating at the Müggelsee in the summer of 2014. However, only the legs of the two women standing on a swing are shown, and upon closer inspection, a man in the background looking directly into the camera.

“Does it bother you that somebody just walked into your picture?

” I ask Birgit. No, he is part of the picture because he shows the elements of chance and of surprise that can result from the self-timer delay. “I knew the moment the photo was taken that it would turn out like this.

” “And how do you feel about your private souvenir photo hanging in other people’s homes?

” “I love this uncontrollable dispersal of my art. And since our faces are not visible, it is anonymous enough as well.

” There is already a waiting list for the photo series – other friends want to be part of the project.

Jerusalem in the Fridge

Birgit Glatzel also enjoys working with a partner on other projects because it inspires the best ideas. That was how it was with the art film Going to Jerusalem that she made with the animation filmmaker Benjamin Seide. It evolved ten years ago as a contribution for an exhibition in Jerusalem on the theme of “Land(e)scaping.” Benjamin and Birgit wanted to address the complex, five-thousand-year history of Jerusalem in an entertaining way, without ridiculing it.

The idea was sparked by a snow globe containing the Jerusalem skyline and a camel that Birgit had been given by a friend, Hagar from Israel – the two of them decided to “liberate” the city skyline from its ball and send it on a world tour accompanied by the camel. So they destroyed the snowball and used both as “leading actors” for her film. Filming locations included the icebox of Birgit’s fridge and the playground opposite her apartment. “Oddly enough, no one in Israel laughed at the film although it is so absurd – for example you see the camel hanging in a cable car over the Alps,

” wonders Birgit. “Your colleague Gelia Eisert was the first to find the film funny.

” “I also had a good laugh,

” I can reassure Birgit.

Since there was only one more public showing of the film in Jerusalem after the exhibition, Birgit has ensured its survival by putting it on a USB stick for our art vending machine. The stick was stuck on a postcard showing the camel in the cable car and the card is lovingly hand-stamped with camel heads designed by Benjamin Seide and Birgit Glatzel. “Working with Benjamin was great fun,

” laughs Birgit. “It was a charming and very special collaboration during the film production and, many years later, designing the card. Unfortunately, this was our only joint project so far.

”

A Friend is a Friend of a Friend

Still of particular importance to Birgit Glatzel is her first major long-term project, which again unites the two motifs from the other works of art – friendship and travel. This was the first project she used the Rolleiflex for – her camera for special occasions, as one photo costs about 2 euros, so you think twice before pressing the shutter. For A Friend is a Friend of a Friend, Birgit sent herself off traveling for four years and visited first friends around the world, then friends of those friends and so on – a total of 340 people, some of whom were friends 16 times removed. “I wanted to show that it’s possible to do it differently and that the Internet does not replace personal experience.

”

Birgit Glatzel took a picture with her Rolleiflex of all the friends and friends of friends she met and with whom she sometimes stayed. The camera was always a good place to start at a first meeting with what were mostly strangers – “It is is an element that we all know and at the same time you can take photos inconspicuously with it, so it is not so intimidating.

” The Rolleiflex was a chance discovery – “I had always wanted a camera like that and came across it when I was looking for a flash for a different camera.

” The photo project led to an exhibition and many years later to a book that Birgit Glatzel financed through a several-month crowdfunding campaign. It shows very many very different people from all around the world in their private environments. The appendix has a list of everyone depicted, listed by place of residence, occupation, or “friendship clan,” to quote Birgit.

Birgit invites me to look through the Rolleiflex at the end. “You see everything back to front,

” says Birgit “but I don’t even notice that anymore.

” She also gives me a signed copy of A Friend is a Friend of a Friend, number 184 of 300, as a reminder of our afternoon together at her studio, which has flown by. The book now has its place on my desk and reminds me that you should send yourself off traveling more often or visit friends or people who you don’t know (yet).

Mariette Franz, Digital & Publishing

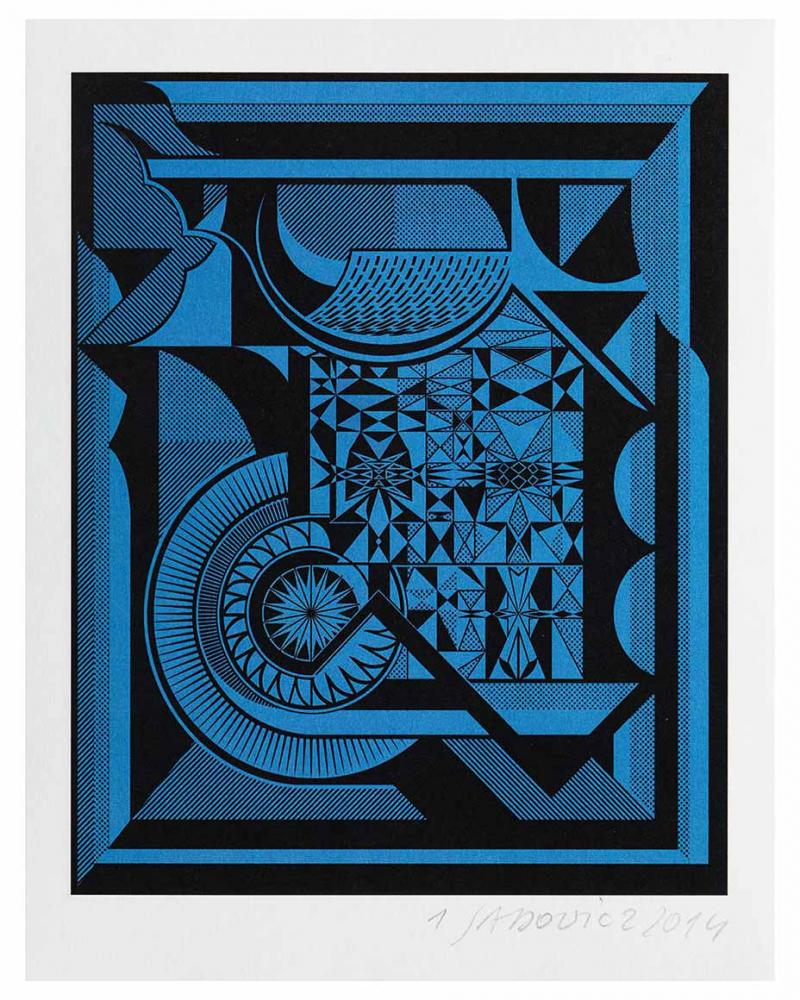

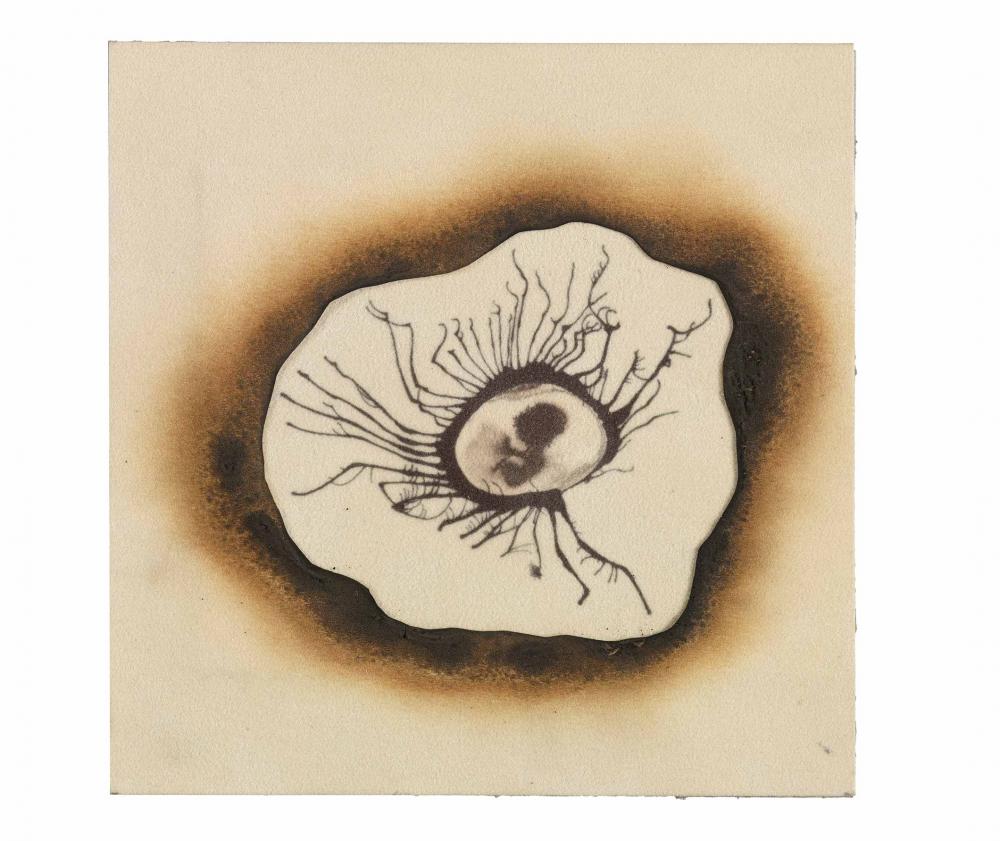

Daniela Orvin (born in Berlin, Germany, 1973), Dyslexic Dysgraphia, 2006, Edition 2015; Jewish Museum Berlin.

Adrift in an Immaculate White Void

Dyslexic dysgraphia—the title of the photo series by Israeli artist Daniela Orvin that was on sale from April 2016 in the Jewish Museum Berlin’s art vending machine is pretty difficult to grasp; but it simply means “difficulty with reading and writing.” “Every one of my artworks is a self-portrait,

” the photographer and musician told me, when I paid her a visit one sunny afternoon at her studio apartment in Berlin-Friedrichshain. She herself has difficulty reading but she was 29 years old before the handicap was detected—despite it having caused considerable disorientation her whole life long.

The Void in My Photos

Place the photos in the Dyslexic dysgraphia series side by side and they resemble the symbols of some bizarre, outlandish language. In reality, they show tree trunks in snow. Daniela Orvin took the photos in Munich, from 2004 to 2006. It was important to her to depict the snow without any trace of a shadow; and so it is that the tree trunks appear to be rootless and isolated, adrift in an immaculate white void.

For our art vending machine, Daniela Orvin mounted her work on acrylic, a painstaking task that forged a personal link between her and each and every image. To my question: “What is the essence of art?” she replied: “The void in my photos.” Loneliness, rootlessness, and the difficulties of interpersonal communication are recurrent themes in her work.

The Language Was in Sleep Mode

The artist was born in Berlin in 1973 and raised in the small town of Ismaning, near Munich, before moving with her family to Israel at the age of 7. It is there that Daniela Orvin spent most of her life to date: in school and in the army; as a student at the renowned Midrasha School of Art in Beit Berl; as co-founder/ curator of a gallery for contemporary photography in Tel Aviv; and as an independent artist, presenting her work in various solo shows. But she never felt she really belonged. In her first years in Israel, she faced exclusion by other kids who saw her as “the German.” This sense of being an outsider has stayed with her ever since.

In 2012 Daniela Orvin moved from Tel Aviv back to her birthplace, Berlin. German is her mother tongue yet she had to relearn it nonetheless; or rather, as she tells me, to reactivate memories of the speech of her childhood: “The language was merely in sleep mode.

” In Berlin she finds the inner peace she needs in order to be able to create: experiences and encounters here, the natural surroundings, and the weather inspire and suffuse her art. More than anything else she loves the intuitive aspects of her work, the unending endeavor to distil the essence of a new project and of photography itself.

Dressur-Wunder

Clear lines, bright light, a sense of calm, and a black and white color scheme are the distinguishing features of Daniela Orvin’s studio apartment. During my visit, she showed me her photo book Dressur-Wunder (The Wonders of Dressage): a volume of images taken from 2007 to 2009 at the Zoologischer Garten in Berlin and the Zirkus Krone in Munich. Here too, Orvin retraces childhood memories, since these are places she visited as a girl with her parents. However, the images betray nothing of the zoo and circus visitors’ enjoyment, but only how solitary and forlorn the animals and artistes appear to feel in the bleak shadows of their respective alienating circumstances. The photographs—no less than the artist herself—are quietly reserved, clinically appraising, and precise.

Maren Krüger, Exhibitions

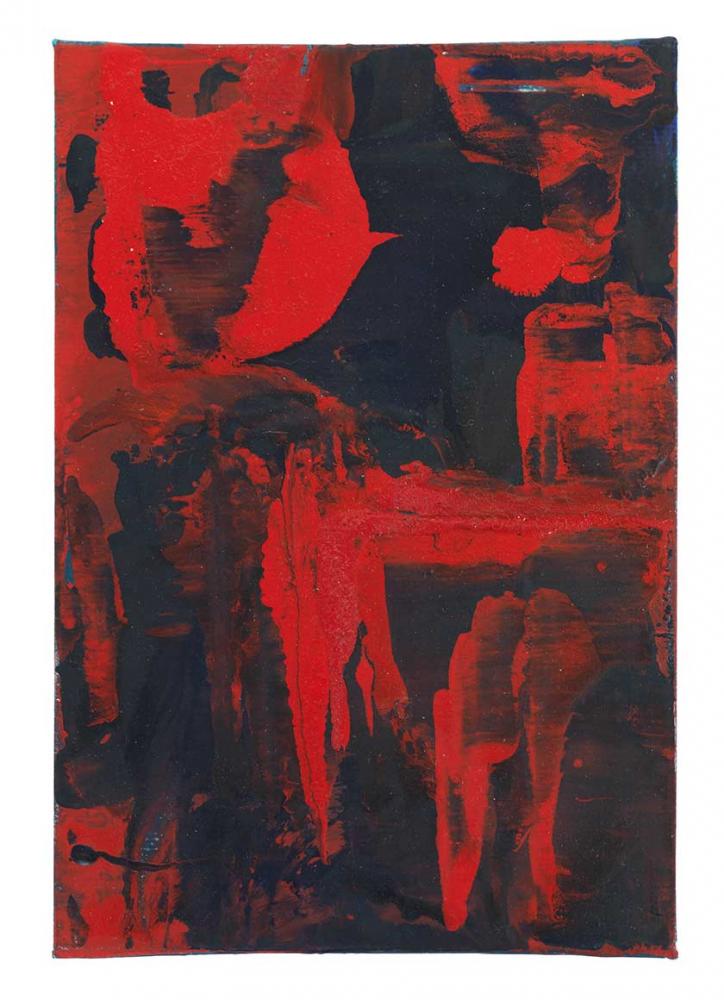

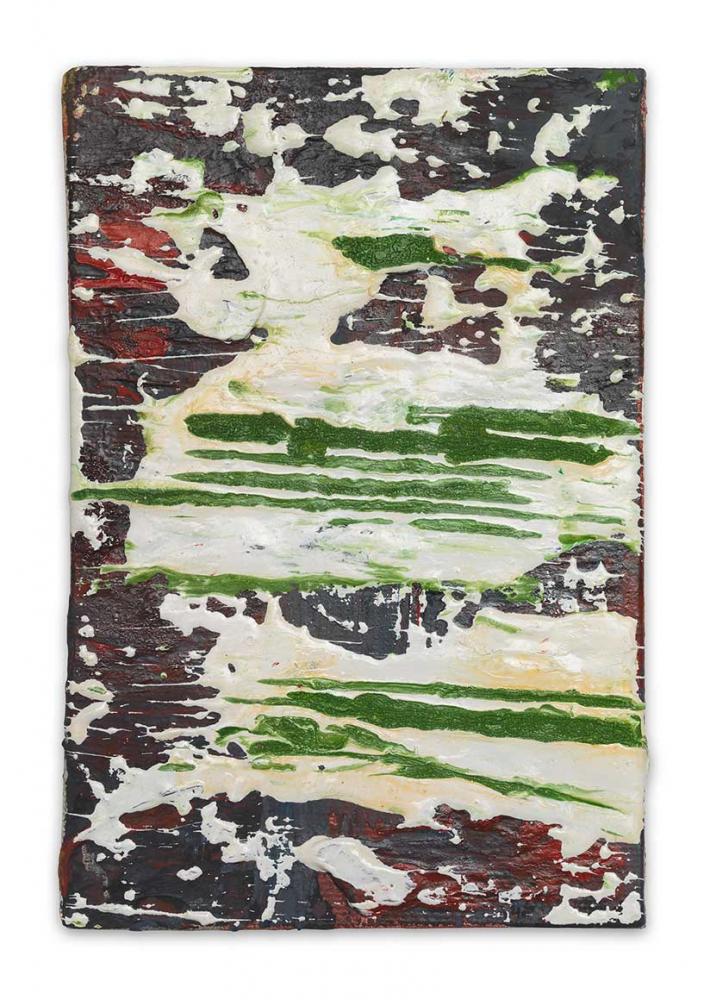

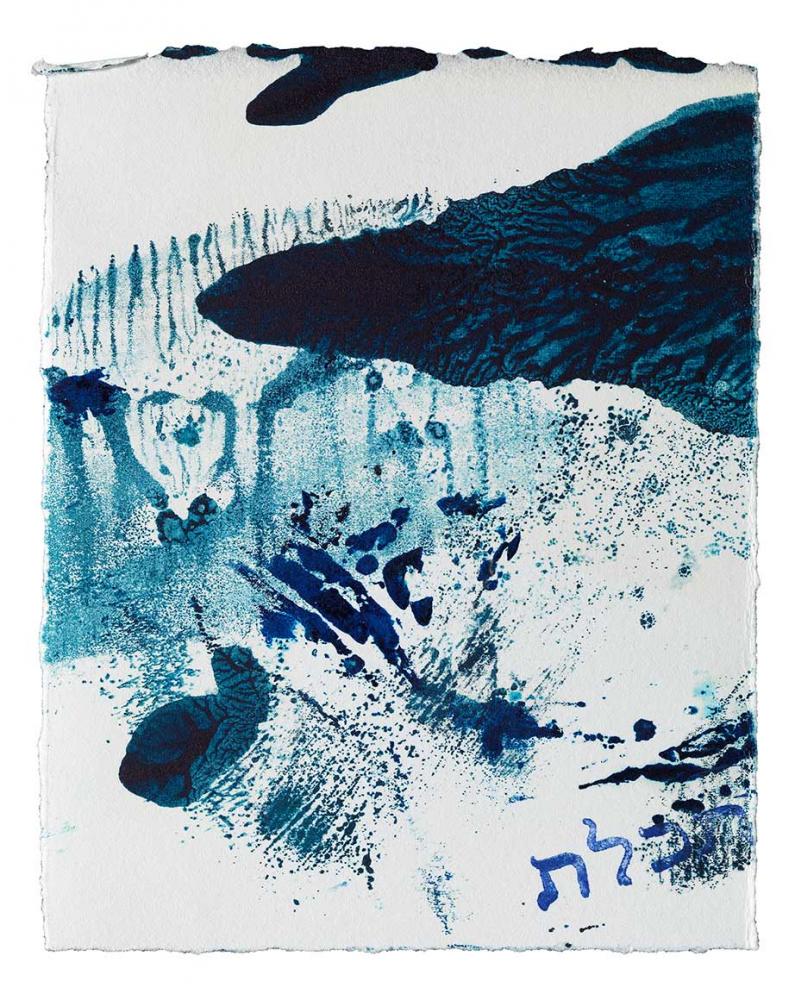

David Benforado (born in Athens, Greece, 1977), Abstract bits from the Painting Makams series, 2014; Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Jens Ziehe.

Painting Music

“There is a whole world in five notes, just as there is a world in five colors.”

With these words David Benforado, painter and musician, expressed his understanding of art. Painting Makams and Between Sound and Silence are, appropriately, the titles of his two series for the art vending machine, both of which were available for sale from 2016 at the Jewish Museum. Music and painting are combined in the small-scale oils, studies in color filled with energy and vitality.

Ever since David Benforado started painting, he has been working with music. His atelier has again and again been the site of sessions with professional musicians, for instance during his time in Budapest with the accordion player David Yengiburgan and here in Berlin with pianist Antonis Anissegos. In 2009 Benforado began studying the ney, a Middle-Eastern flute, and soon he encountered the world of Turkish makams and modal music from the eastern Mediterranean. This became a source of inspiration for his painting.

The Light on Syros

David Benforado grew up in Greece. The particular light of that region is, as he says, “a part of me”

. A two-year sojourn on the Greek island of Syros was especially formative for him. Through the daily and seasonal rhythm he observed and analyzed the light, with all of its nuances, its transformations. He developed a new perception of color and new ways of using it.

Of the 400 oil paintings in the two series for the art vending machine, each one unique, the artist used two different techniques for painting. He himself mixed the paints from pigment, as always. In the first variant, he spread a number of layers of paint on top of one another. The paints dried in the interim, the last layer following the method “wet-on-wet”. With the second technique the paint got applied all in one batch, in connection with his listening to modal music. The makams underlying this music – series of tones, each marked by certain intervals and a characteristic melodic progression – all stand for different emotions. Every painting conveys the timbre and acoustic color of a specific makam. These works are studies for larger paintings.

Benforado’s paintings evoke associations with nature: surges, waves, fire, wind, the rustling of leaves, sunlight, and sky. Each with its own distinct personality, they invite a kind of meditative immersion and, in addition, the discovery of what might be below the surface.

Leonore Maier, Collections

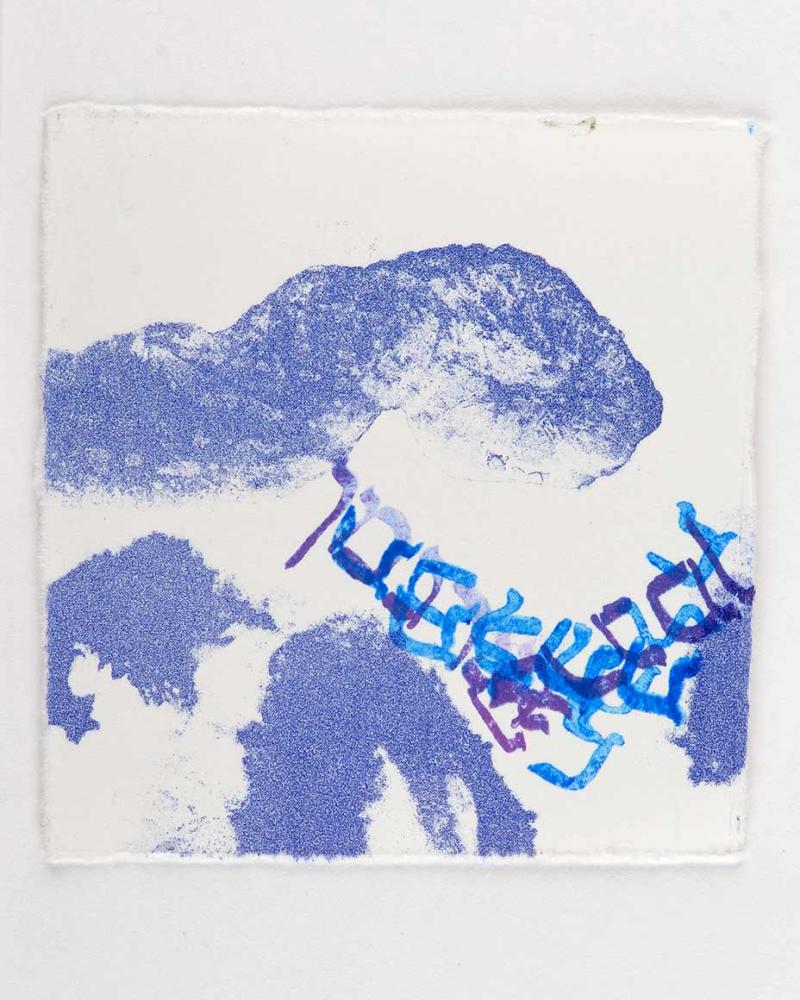

David Benforado (born in Athens, Greece, 1977), Abstract bits from the Between Sound and Silence series, 2015; Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Jens Ziehe.

Painting Music

“There is a whole world in five notes, just as there is a world in five colors.”

With these words David Benforado, painter and musician, expressed his understanding of art. Painting Makams and Between Sound and Silence are, appropriately, the titles of his two series for the art vending machine, both of which were available for sale from 2016 at the Jewish Museum. Music and painting are combined in the small-scale oils, studies in color filled with energy and vitality.

Ever since David Benforado started painting, he has been working with music. His atelier has again and again been the site of sessions with professional musicians, for instance during his time in Budapest with the accordion player David Yengiburgan and here in Berlin with pianist Antonis Anissegos. In 2009 Benforado began studying the ney, a Middle-Eastern flute, and soon he encountered the world of Turkish makams and modal music from the eastern Mediterranean. This became a source of inspiration for his painting.

The Light on Syros

David Benforado grew up in Greece. The particular light of that region is, as he says, “a part of me”

. A two-year sojourn on the Greek island of Syros was especially formative for him. Through the daily and seasonal rhythm he observed and analyzed the light, with all of its nuances, its transformations. He developed a new perception of color and new ways of using it.

Of the 400 oil paintings in the two series for the art vending machine, each one unique, the artist used two different techniques for painting. He himself mixed the paints from pigment, as always. In the first variant, he spread a number of layers of paint on top of one another. The paints dried in the interim, the last layer following the method “wet-on-wet”. With the second technique the paint got applied all in one batch, in connection with his listening to modal music. The makams underlying this music – series of tones, each marked by certain intervals and a characteristic melodic progression – all stand for different emotions. Every painting conveys the timbre and acoustic color of a specific makam. These works are studies for larger paintings.

Benforado’s paintings evoke associations with nature: surges, waves, fire, wind, the rustling of leaves, sunlight, and sky. Each with its own distinct personality, they invite a kind of meditative immersion and, in addition, the discovery of what might be below the surface.

Leonore Maier, Collections

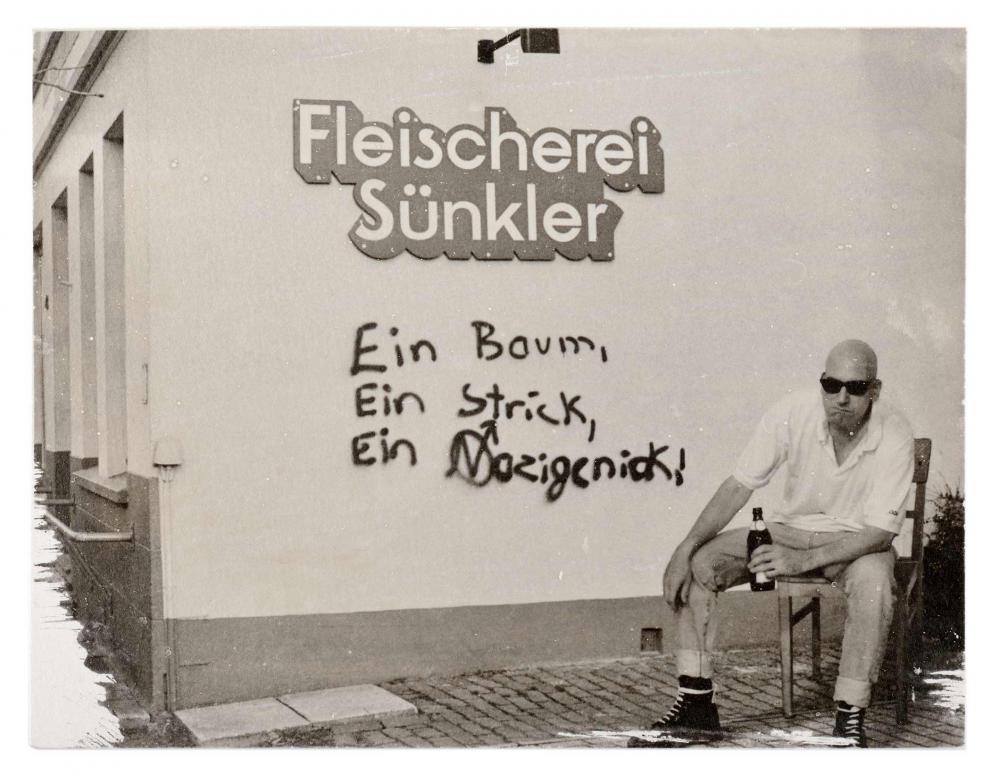

Joachim Seinfeld (born in Paris, France, 1962), HeimatReisen – Oldenburg; Jewish Museum Berlin.

“Art has to be for everyone” Joachim Seinfeld’s HeimatReisen (HomelandTravels)

The wonderful thing about Berlin for me as an historian is that there’s something around every corner waiting to wow me or get my “history heart” to skip a beat. In the year 2016 I was able to get to know yet another spot when I interviewed Joachim Seinfeld in his atelier in the old broadcasting station in the Berlin Treptow-Köpenick district. We talked about his HeimatReisen (HomelandTravels) project for the art vending machine at the Jewish Museum Berlin.

The broadcasting station on Nalepastrasse is a unique place: Beginning in 1956, programming across the former GDR was produced and broadcast from there. The public broadcasting system, established following German reunification, took over this work in 1991 and then, after several changes in ownership, the building became a place for artists from around the world to establish their ateliers.

Michaela Roßberg: Joachim, your photo series – available to visitors in the art vending machine – consists of a number of images depicting you in various locations around Germany. Why, of all your work, these images for the vending machine?

Joachim Seinfeld: In 2006, I did a photo series about Poland. In 2011, I thought to do something similar about Germany. So I wanted to do it anyway, and I chose the images most interesting to me.

Michaela Roßberg: So are the places in the images you yourself are part of also situations from your life?

Joachim Seinfeld: Poland, Germany and Italy are countries I’ve spent extended periods of time in and I attach importance to. I wanted to create a trilogy for these countries with the photo series. The images are largely connected to places I’ve spent a long time in, or nearby. I’m from Munich and lived in Italy, then Oldenburg, and worked two years in Poland. Now I’ve been a long time in Berlin. The altered or modified photos of the places in HeimatReisen play with concepts and clichés of a supposedly typical Germany.

Michaela Roßberg: Is the takeaway with the title, HeimatReisen, that you don’t feel at home in these places?

Joachim Seinfeld: Yes. When I think about the subject of homeland, I always come back to the word, yurt. It’s the Turkish word for homeland, and the yurt, tent, which nomads use for housing, comes from this word. It’s a home you can take with you in your travels. In this sense, HeimatReisen. The only place I really feel at home is in the mountains – the landscape of my childhood. Homeland for me is more a feeling than a particular place. It has to do with my life situation. And it for sure isn’t connected to a feeling of national pride.

Michaela Roßberg: Would your understanding of “homeland” be different for you if you didn’t live in Germany?

Joachim Seinfeld: Quite possibly. The problem is that the German understanding has been completely discredited due to German history and misappropriation of the word. There’s also a positive connotation that has more to do with being and feeling at home. I’m much more comfortable with this than, for example, the Italian word for homeland, patria. That conjures up images of the goosestep in my mind.

Michaela Roßberg: Other countries often have a more natural connection to the idea of homeland. Is this a “German problem?”

Joachim Seinfeld: To a degree, yes, though I personally have a problem with it in other countries’ contexts, too, especially when the concept of homeland approaches the realm of patriotism. I’m of the opinion that the word “patriotism” is itself too closely tied to thinking that one’s own country is better than another’s, and you’re better than someone else. These days, when travel is so much easier and you can experience so many more perspectives, I don’t think we need to be constrained to this idea of homeland. I think we can also find our identity elsewhere.

Michaela Roßberg: What do you want to say with your work? As a viewer, I asked myself: What do you, for example, want to say to me with the Oldenburg work? Something about how many neo-Nazis are in this city?

Joachim Seinfeld: The work contains many facets and discussion points that I address with irony. HeimatReisen also means the images can contain things that I as a traveler or observer could have captured. The Oldenburg staging is of course bathed in cliché. I generally like to do that, but it’s always relevant either to history or current developments. For example, Oldenburg in addition to Weimar had a Nazi administration before 1933, and the region was a playground for their ilk in the 1990s.

Michaela Roßberg: But what should a viewer of your images be thinking? Do you have something particular in mind?

Joachim Seinfeld: That’s not how art works. You don’t make art because people should see something in particular. Then it’s didactic pedagogy or agitprop. You just make art shaped by your thoughts and ideas, and you’re lucky should people happen to get from it what you intended. The artist has to accept the risk that the viewer may have a completely contrary interpretation.

Michaela Roßberg: That explains why I’m not an artist – that’d make me too insecure.

Joachim Seinfeld: You don’t work completely blind; you get feedback a number of ways: If you’ve been making art for 20 years and no one wants to look at it, that’s also a kind of reaction.

Michaela Roßberg: Why are you as yourself always worked into the images?

Joachim Seinfeld: First of all, it’s unbelievable fun to make theater out of it. Second of all, I’m of the opinion that a person is shaped by all aspects of a society. So why should I use another person in the staging? There are exemplary images of this in HeimatReisen and it’s pretty irrelevant who’s pictured in those. Of course I bring individual aspects into the work, for example the “Super Jew” in Friedrichhain. The “Super Jew” kicks over the stoplight, which is actually a pointless action, but he’s very satisfied nonetheless. Sometimes you take yourself too seriously (laughs).

Michaela Roßberg: Is it satisfying for you as an artist when your work is available for 6 euros in a museum vending machine?

Joachim Seinfeld: Sure. I think the idea of an art vending machine is superb. Art has to be for everyone. It’s not just for the wealthy, but should be accessible for all people – also outside a museum.

Michaela Roßberg, Temporary Exhibitions

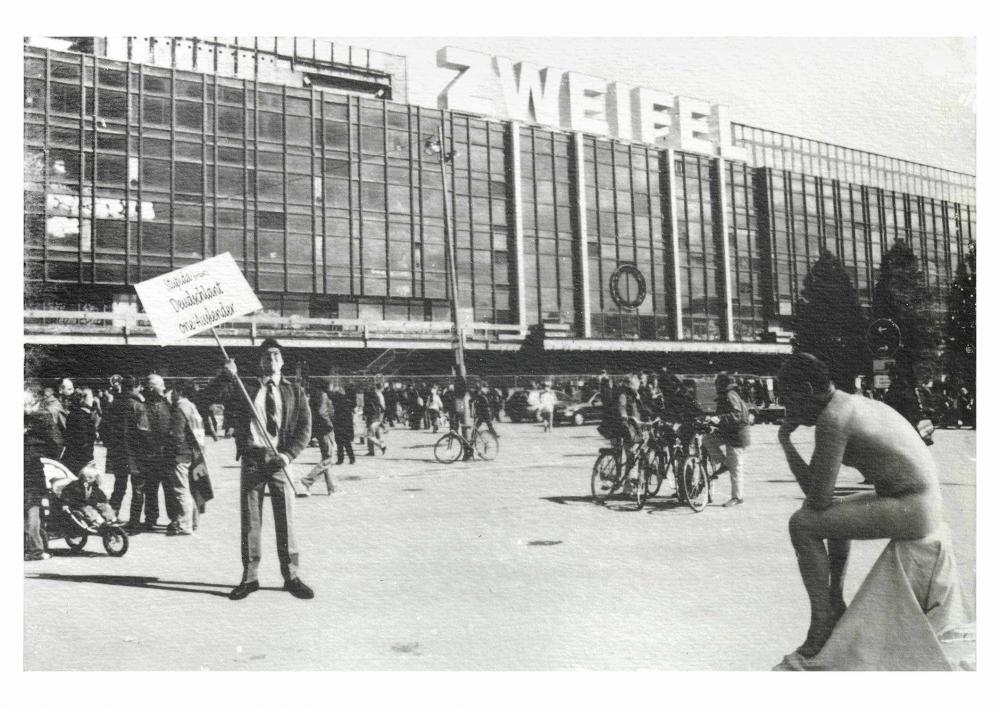

Joachim Seinfeld (born in Paris, France, 1962), HeimatReisen – Berlin-Schlossplatz; Jewish Museum Berlin

“Art has to be for everyone” Joachim Seinfeld’s HeimatReisen (HomelandTravels)

The wonderful thing about Berlin for me as an historian is that there’s something around every corner waiting to wow me or get my “history heart” to skip a beat. In the year 2016 I was able to get to know yet another spot when I interviewed Joachim Seinfeld in his atelier in the old broadcasting station in the Berlin Treptow-Köpenick district. We talked about his HeimatReisen (HomelandTravels) project for the art vending machine at the Jewish Museum Berlin.

The broadcasting station on Nalepastrasse is a unique place: Beginning in 1956, programming across the former GDR was produced and broadcast from there. The public broadcasting system, established following German reunification, took over this work in 1991 and then, after several changes in ownership, the building became a place for artists from around the world to establish their ateliers.

Michaela Roßberg: Joachim, your photo series – available to visitors in the art vending machine – consists of a number of images depicting you in various locations around Germany. Why, of all your work, these images for the vending machine?

Joachim Seinfeld: In 2006, I did a photo series about Poland. In 2011, I thought to do something similar about Germany. So I wanted to do it anyway, and I chose the images most interesting to me.

Michaela Roßberg: So are the places in the images you yourself are part of also situations from your life?

Joachim Seinfeld: Poland, Germany and Italy are countries I’ve spent extended periods of time in and I attach importance to. I wanted to create a trilogy for these countries with the photo series. The images are largely connected to places I’ve spent a long time in, or nearby. I’m from Munich and lived in Italy, then Oldenburg, and worked two years in Poland. Now I’ve been a long time in Berlin. The altered or modified photos of the places in HeimatReisen play with concepts and clichés of a supposedly typical Germany.

Michaela Roßberg: Is the takeaway with the title, HeimatReisen, that you don’t feel at home in these places?

Joachim Seinfeld: Yes. When I think about the subject of homeland, I always come back to the word, yurt. It’s the Turkish word for homeland, and the yurt, tent, which nomads use for housing, comes from this word. It’s a home you can take with you in your travels. In this sense, HeimatReisen. The only place I really feel at home is in the mountains – the landscape of my childhood. Homeland for me is more a feeling than a particular place. It has to do with my life situation. And it for sure isn’t connected to a feeling of national pride.

Michaela Roßberg: Would your understanding of “homeland” be different for you if you didn’t live in Germany?

Joachim Seinfeld: Quite possibly. The problem is that the German understanding has been completely discredited due to German history and misappropriation of the word. There’s also a positive connotation that has more to do with being and feeling at home. I’m much more comfortable with this than, for example, the Italian word for homeland, patria. That conjures up images of the goosestep in my mind.

Michaela Roßberg: Other countries often have a more natural connection to the idea of homeland. Is this a “German problem?”

Joachim Seinfeld: To a degree, yes, though I personally have a problem with it in other countries’ contexts, too, especially when the concept of homeland approaches the realm of patriotism. I’m of the opinion that the word “patriotism” is itself too closely tied to thinking that one’s own country is better than another’s, and you’re better than someone else. These days, when travel is so much easier and you can experience so many more perspectives, I don’t think we need to be constrained to this idea of homeland. I think we can also find our identity elsewhere.

Michaela Roßberg: What do you want to say with your work? As a viewer, I asked myself: What do you, for example, want to say to me with the Oldenburg work? Something about how many neo-Nazis are in this city?

Joachim Seinfeld: The work contains many facets and discussion points that I address with irony. HeimatReisen also means the images can contain things that I as a traveler or observer could have captured. The Oldenburg staging is of course bathed in cliché. I generally like to do that, but it’s always relevant either to history or current developments. For example, Oldenburg in addition to Weimar had a Nazi administration before 1933, and the region was a playground for their ilk in the 1990s.

Michaela Roßberg: But what should a viewer of your images be thinking? Do you have something particular in mind?

Joachim Seinfeld: That’s not how art works. You don’t make art because people should see something in particular. Then it’s didactic pedagogy or agitprop. You just make art shaped by your thoughts and ideas, and you’re lucky should people happen to get from it what you intended. The artist has to accept the risk that the viewer may have a completely contrary interpretation.

Michaela Roßberg: That explains why I’m not an artist – that’d make me too insecure.

Joachim Seinfeld: You don’t work completely blind; you get feedback a number of ways: If you’ve been making art for 20 years and no one wants to look at it, that’s also a kind of reaction.

Michaela Roßberg: Why are you as yourself always worked into the images?

Joachim Seinfeld: First of all, it’s unbelievable fun to make theater out of it. Second of all, I’m of the opinion that a person is shaped by all aspects of a society. So why should I use another person in the staging? There are exemplary images of this in HeimatReisen and it’s pretty irrelevant who’s pictured in those. Of course I bring individual aspects into the work, for example the “Super Jew” in Friedrichhain. The “Super Jew” kicks over the stoplight, which is actually a pointless action, but he’s very satisfied nonetheless. Sometimes you take yourself too seriously (laughs).

Michaela Roßberg: Is it satisfying for you as an artist when your work is available for 6 euros in a museum vending machine?

Joachim Seinfeld: Sure. I think the idea of an art vending machine is superb. Art has to be for everyone. It’s not just for the wealthy, but should be accessible for all people – also outside a museum. Michaela Roßberg, Temporary Exhibitions

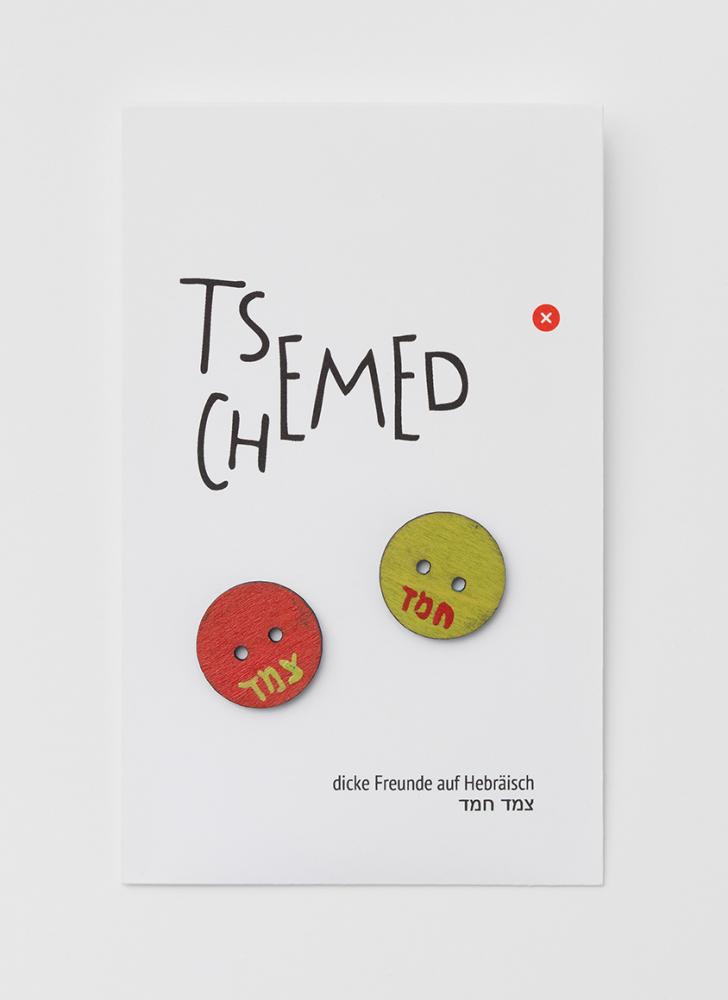

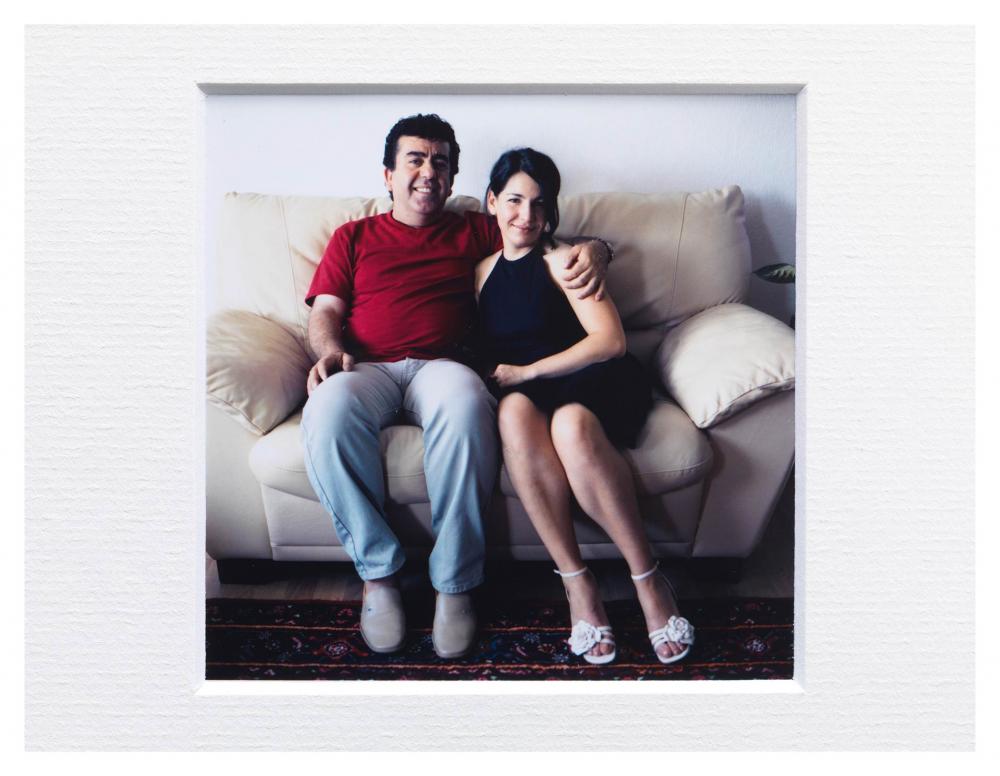

Noga Shtainer (born in Safed, Israel, 1982), Twins: Duo Morality, Edition, 2015, #1; Jewish Museum Berlin.

In the Shadow of the Mengele Myth

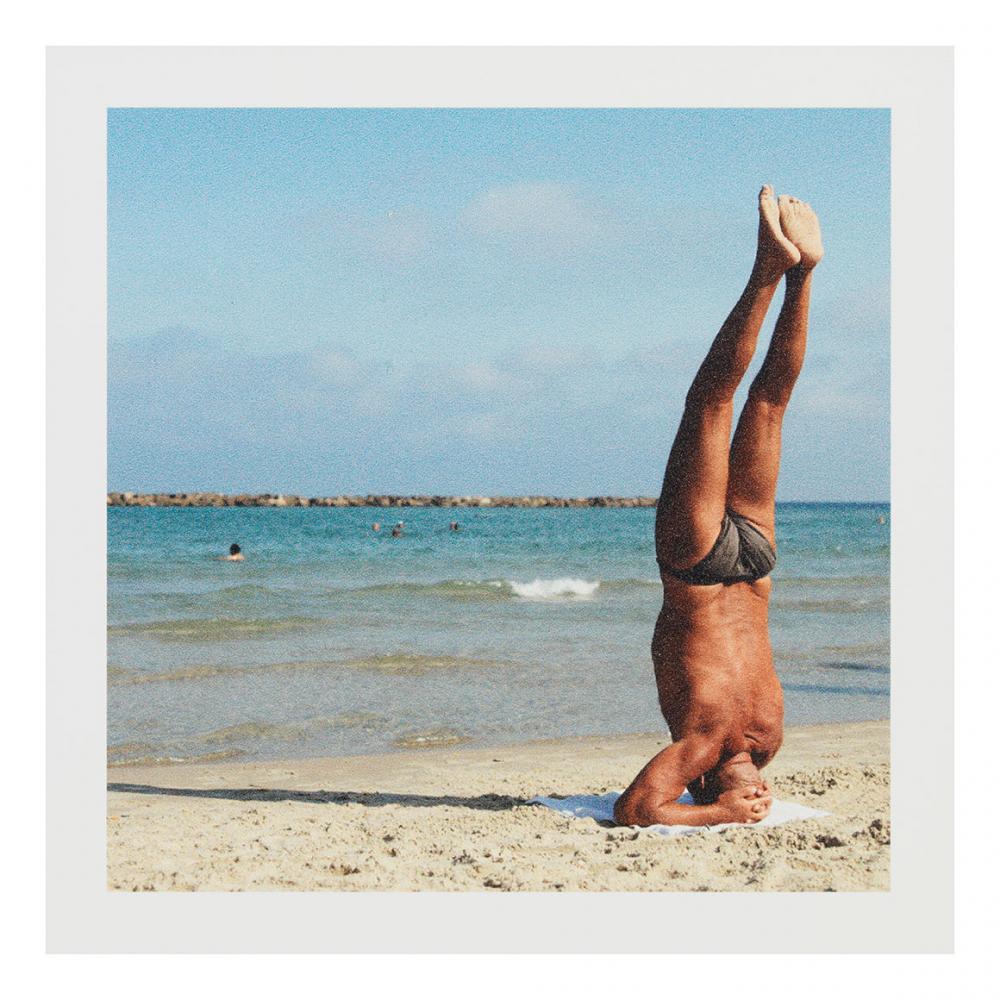

Noga Shtainer often travels with her camera in tow, for her photography project Home for Special Children in the Ukraine, for instance, or for Twins in Brazil. Shots from the latter project were available for purchase from the art vending machine in 2016. The photographer has lived since 2010 in Berlin, where I first met her in 2014.

Application trick

The fact that Noga Shtainer is a photographer is itself accidental. She set out to become an actress. But she didn’t pass the entrance auditions for the WIZO School of Art in Haifa and was encouraged instead to apply for a photography class. The deadline for submitting an application portfolio was only two days away, however. So she simply handed in an envelope stuffed with photos and claimed that they were pictures she had taken of her half-sister. In fact, they were photographs from a family album, showing Noga Shtainer herself as a young girl. The trick was successful and Noga Shtainer was accepted at the age of 15 into the WIZO School of Art. Thus began her career as a photographer.

The Differences in What Seems the Same

Photo portraits by Noga Shtainer are distinguished by their commitment and intensity. You can see this in the series “Twins – Duo Morality”. The similarity between two genetically identical people, and the simultaneous desire of the onlooker to differentiate between them, provoked Shtainer’s curiosity. In Israel she had already begun through photography to register the inequalities present in things that are apparently the same. In 2010 she pursued an unlikely trail into the dark history of Nazi ideology’s racial fanaticism: in Cândido Gódoi in southern Brazil, the unusually high density of twins supposedly has a connection to experiments by Josef Mengele. The town consists predominantly of German and Polish immigrants and their descendants who settled in southern Brazil during the First World War. Mengele allegedly lived and practiced medicine in the area in the 1960s, passing undetected under an assumed name. He had carried out brutal medical trials on Jewish prisoners at Auschwitz, including numerous barbaric experiments on twins. He may then have used the results in a variety of treatments on his patients in Brazil. According to some reports, this was why an unusual number of identical twins were born in that region. This story cannot be proven historically nor is there adequate evidence of genetically manipulated pregnancies in Cândido Gódoi. The many blond, blue-eyed pairs of twins, however, gave and continue to give new life to the Mengele Myth, still spurring the imagination of authors, filmmakers, and journalists today.

The Myth Becomes Secondary

When Noga Shtainer arrived in Cândido Gódoi, she first needed to go in search of her models, since twins don’t always make appearances together. A period of intense investigation, going door-to-door and zealously polling neighborhoods, led Noga to find 50 pairs of twins who were prepared to be photographed.

Noga Shtainer’s intention to get to the bottom of this story became secondary to the artistic statement she was making. In the foreground of the series we see the twins in their residential environment, in the backyard or on the terrace: they look almost identical but on closer examination of the photographs one begins to distinguish between them. I caught myself, while observing the pictures, getting excited every time I noticed a difference between a pair of twins. Sometimes it’s the hair, the figure, perhaps a slight variation in the nose or eyes, or a little birthmark. It trains one to look more closely and to see more detail, to compare the surroundings, the position of both people in the image, and perhaps even to question their relationship to one another. As those portrayed become more familiar to the observer, the apparent conformity disappears as one recognizes that each twin is an individual.

Two by Two

For the art vending machine in the permanent exhibition of the Jewish Museum Berlin, Noga Shtainer embarked on an experiment, showing her work in an unusual format. Normally she presents her work on a scale large enough to cover the whole wall, which would of course not have been feasible for the rather compact vending machine with its art treasures. But she took up the challenge and is showing her work here on a proportionately smaller scale, and at the same time doubled up: two copies of four versions of each pair of twins (appropriate enough given the theme). When one looks for instance at the pair of twins called Nelson and Norbert as they search with their Wilhelmine mustaches for the right position to stand in at the garden fence, the autographed pictures seem to contain entire little stories.

Incidentally, after her lucky break getting into the Haifa academy, Shtainer did in fact photograph her half-sister. For twelve straight years she took a picture of Ella on every Shabbat for her series Near Conscious. The intense photographs that emerged show a young girl growing up. In the meantime, Noga Shtainer is now by one of the most renowned galleries in Israel and had shows in Berlin as well through the middle of last February of her series Wagenburg and Near Conscious.

Jihan Radjai, Exhibition and Collections.

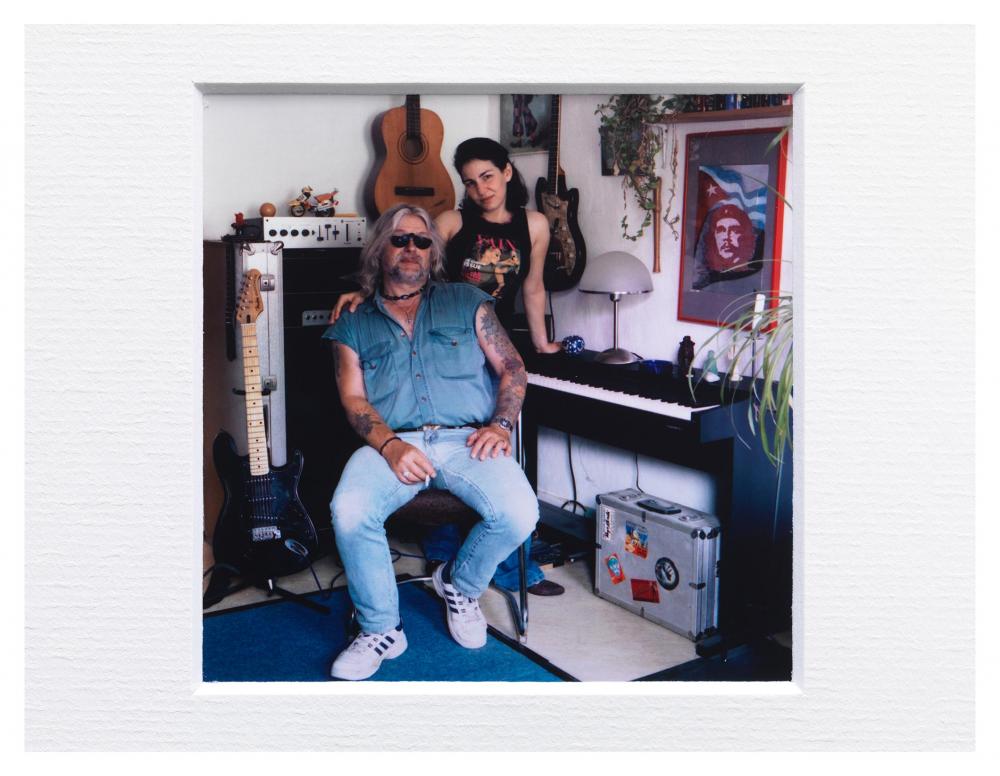

Noga Shtainer (born in Safed, Israel, 1982), Twins: Duo Morality, Edition, 2015, #2; Jewish Museum Berlin.

In the Shadow of the Mengele Myth

Noga Shtainer often travels with her camera in tow, for her photography project Home for Special Children in the Ukraine, for instance, or for Twins in Brazil. Shots from the latter project were available for purchase from the art vending machine in 2016. The photographer has lived since 2010 in Berlin, where I first met her in 2014.

Application trick

The fact that Noga Shtainer is a photographer is itself accidental. She set out to become an actress. But she didn’t pass the entrance auditions for the WIZO School of Art in Haifa and was encouraged instead to apply for a photography class. The deadline for submitting an application portfolio was only two days away, however. So she simply handed in an envelope stuffed with photos and claimed that they were pictures she had taken of her half-sister. In fact, they were photographs from a family album, showing Noga Shtainer herself as a young girl. The trick was successful and Noga Shtainer was accepted at the age of 15 into the WIZO School of Art. Thus began her career as a photographer.

The Differences in What Seems the Same

Photo portraits by Noga Shtainer are distinguished by their commitment and intensity. You can see this in the series “Twins – Duo Morality”. The similarity between two genetically identical people, and the simultaneous desire of the onlooker to differentiate between them, provoked Shtainer’s curiosity. In Israel she had already begun through photography to register the inequalities present in things that are apparently the same. In 2010 she pursued an unlikely trail into the dark history of Nazi ideology’s racial fanaticism: in Cândido Gódoi in southern Brazil, the unusually high density of twins supposedly has a connection to experiments by Josef Mengele. The town consists predominantly of German and Polish immigrants and their descendants who settled in southern Brazil during the First World War. Mengele allegedly lived and practiced medicine in the area in the 1960s, passing undetected under an assumed name. He had carried out brutal medical trials on Jewish prisoners at Auschwitz, including numerous barbaric experiments on twins. He may then have used the results in a variety of treatments on his patients in Brazil. According to some reports, this was why an unusual number of identical twins were born in that region. This story cannot be proven historically nor is there adequate evidence of genetically manipulated pregnancies in Cândido Gódoi. The many blond, blue-eyed pairs of twins, however, gave and continue to give new life to the Mengele Myth, still spurring the imagination of authors, filmmakers, and journalists today.

The Myth Becomes Secondary

When Noga Shtainer arrived in Cândido Gódoi, she first needed to go in search of her models, since twins don’t always make appearances together. A period of intense investigation, going door-to-door and zealously polling neighborhoods, led Noga to find 50 pairs of twins who were prepared to be photographed.

Noga Shtainer’s intention to get to the bottom of this story became secondary to the artistic statement she was making. In the foreground of the series we see the twins in their residential environment, in the backyard or on the terrace: they look almost identical but on closer examination of the photographs one begins to distinguish between them. I caught myself, while observing the pictures, getting excited every time I noticed a difference between a pair of twins. Sometimes it’s the hair, the figure, perhaps a slight variation in the nose or eyes, or a little birthmark. It trains one to look more closely and to see more detail, to compare the surroundings, the position of both people in the image, and perhaps even to question their relationship to one another. As those portrayed become more familiar to the observer, the apparent conformity disappears as one recognizes that each twin is an individual.

Two by Two

For the art vending machine in the permanent exhibition of the Jewish Museum Berlin, Noga Shtainer embarked on an experiment, showing her work in an unusual format. Normally she presents her work on a scale large enough to cover the whole wall, which would of course not have been feasible for the rather compact vending machine with its art treasures. But she took up the challenge and is showing her work here on a proportionately smaller scale, and at the same time doubled up: two copies of four versions of each pair of twins (appropriate enough given the theme). When one looks for instance at the pair of twins called Nelson and Norbert as they search with their Wilhelmine mustaches for the right position to stand in at the garden fence, the autographed pictures seem to contain entire little stories.

Incidentally, after her lucky break getting into the Haifa academy, Shtainer did in fact photograph her half-sister. For twelve straight years she took a picture of Ella on every Shabbat for her series Near Conscious. The intense photographs that emerged show a young girl growing up. In the meantime, Noga Shtainer is now by one of the most renowned galleries in Israel and had shows in Berlin as well through the middle of last February of her series Wagenburg and Near Conscious.

Jihan Radjai, Exhibition and Collections.

Rachel Kohn (born in Prague, Czechoslovak Republic, today Czech Republic, 1962), 100 Chairs, 100 Houses; Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Jens Ziehe.

Ceramics for all situations Friends of the Jewish Museum Berlin visit Rachel Kohn

In advance of Rachel Kohn’s work entering our art vending machine, the Friends of the Jewish Museum Berlin had the foresight to paid the artist a visit at her atelier in Berlin Charlottenburg. It was the fourth installment of the art vending machine, for which Kohn has created miniature chairs and houses we could already marvel at during the visit.

Stepping into the atelier in this cozy home, we’re greeted by colorful dishes and fantastical judaica. Small houses and chairs made of clay are displayed on the walls in rows, and sculptures sit majestically atop their white pedestals. The air fills with the aromatic warmth of fresh coffee and tea poured into handmade cups. It’s an inviting welcome.

A Life Leading to the Art Studio

Rachel Kohn was born in Prague and moved to Munich to begin her career in sculpting and ceramics at the Akademie der Bildenden Künste (Academy of Visual Arts) there. Following an academic exchange at the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design in Jerusalem and additional travel to Bolivia and Mexico, she moved to Berlin in 1993 with her husband. By now, she’s exhibited in galleries throughout Germany and currently sits on the board of the Berlin Women’s Museum, which supports the professional development of female artists.

Our atelier visit begins with brightly colored ceramics piled high on a narrow shelf. Rachel handles each piece, regardless of size, a minimum of 10 times before she’s finished with it. The plates, cups, butter dishes and “Rachel’s ceramic Tupperware” all get the artist’s treatment with painting and decoration. Every item is unique and exceedingly imaginative. With such immense variety, even Rachel can be caught by surprised when she comes across items she’s sold years earlier. She draws her inspiration from the everyday, which is evident in her ceramic’s design: Some vases have multiple parts, suitable for both thin, narrow flowers and stout, voluptuous bouquets. The lid for the stack of cans functions also as a plate and, bathroom aesthetics not to be overlooked, the toilet brush holder is meticulously decorated.

Houses, chairs, Families

Having shown us everyday items, Rachel moves onto a number of clay and bronze sculptures. The recurring house and chair motif, which was part of our art vending machine in 2016, deals with the artist’s perspective of family and interpersonal relationships. The simple chairs can be easily rearranged to allow for various kinds of communication – one arrangement suggesting conversation, another conflict. What makes Rachel’s work particularly interesting is its openness to interpretation.

There are more highlights of the atelier visit: A large sculpture of a dance partners cast in bronze, as well as a white, child’s bed caught in the shadow of a menacing, black cloud. The sculpture is a template for a memorial to child victims of forced labor during the Second World War. The sculpture itself was inaugurated in 2009 by the community of Otterndorf in Lower Saxony.

Christmas-Chanukkia

She concludes with showing us her judaica, some of which you can find in our museum shop. We take particular note of the Hanukkiah assuming the form of a Christmas tree – perfect for any Christmakah celebration! Her seder plates, mezuzot and kiddush cups, which can be quickly converted into everyday use, speak volumes of her creative spectrum. For example, a container that looks like a Hanukkiah when first opened becomes, when turned, Shabbat candles. No need to wait a year to use it again.

Lea Ledwon, Events

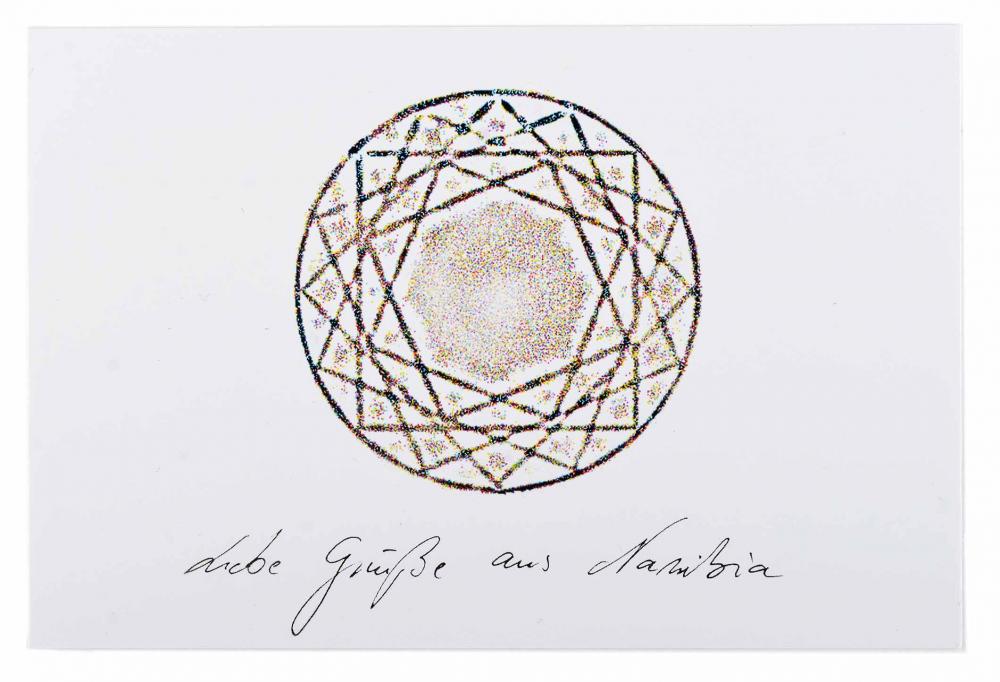

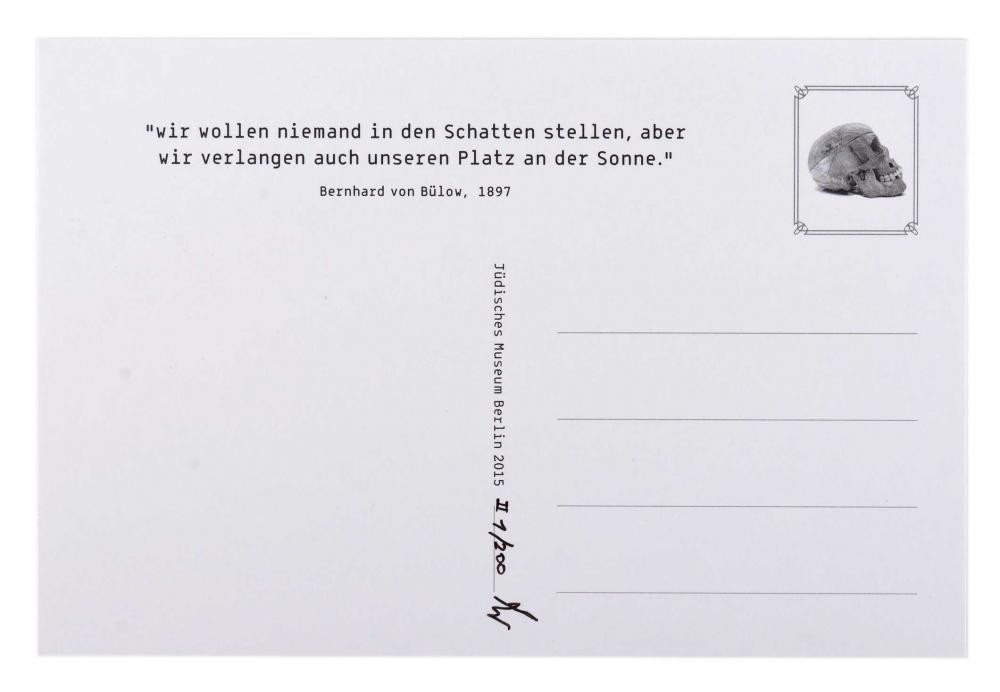

Shira Wachsmann (born in Tel Aviv, Israel, 1984), Liebe Grüße aus Namibia, Postcard, 2015; Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Jens Ziehe.

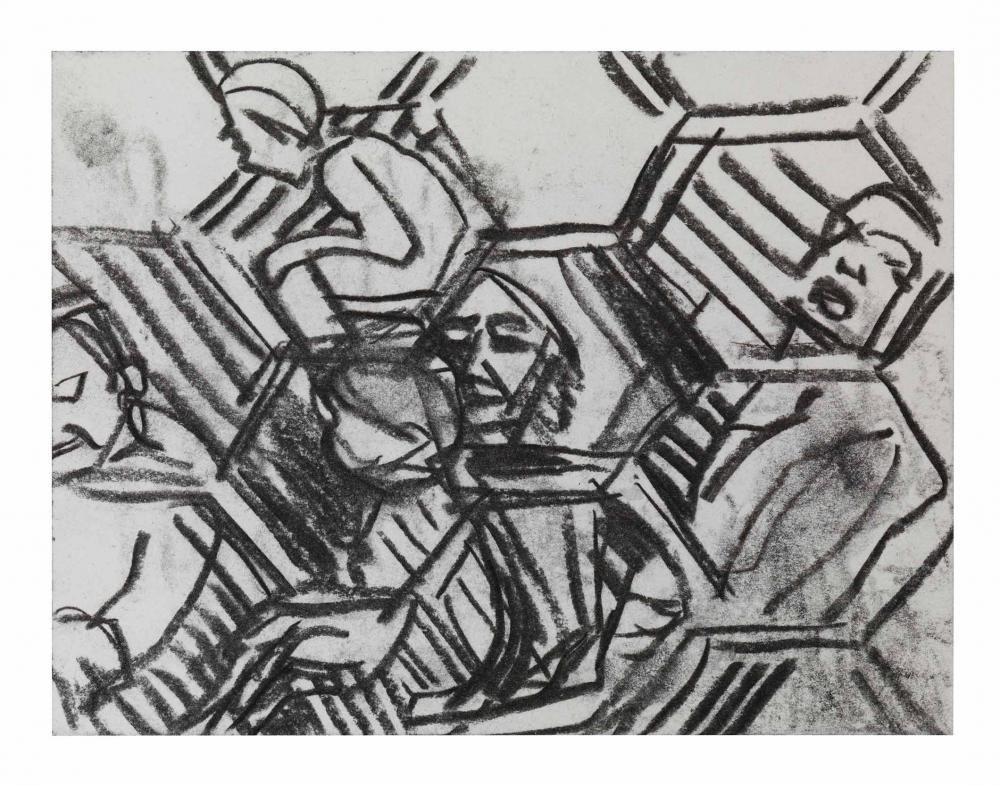

A Reminder in the Mail - the Nearly Forgotten Genocide of the Herero and Nama Peoples in Present-Day Namibia

The streets of Kreuzberg are soaked through with rain on this grey February day. Shira Wachsmann, a graceful young woman with short black hair, leads me into her atelier in a pre-war apartment. She doesn’t have much time. Her solo exhibition Tribe Fire was scheduled to open on 13 March 2016 in the gallery cubus-m in Berlin’s Schöneberg neighborhood. It remained there until 23 April 2016. Large drawings, soon to become part of the Tribe Fire installation, hang in the atelier. “There’s still a lot to do,

” the Israeli native explains.

Circled in, Cast out

One of her projects is spread across her desk: two postcards that Wachsmann designed for the Jewish Museum Berlin. She produced editions of 400 of each piece, which were available for individual purchase in 2016 in the art vending machine of the museum’s permanent exhibition. Wachsmann takes a seat in a green armchair and ponders the cards. They show two circular motifs, a form that appears throughout the artist’s work like a guiding principle. Here they depict an abstract diamond and a black sun.

“My pre-occupation with the circle motif started in 2012, when I found a map of Palestine from the period of the British Mandate in a second-hand bookshop in Israel,

” she recalls, pointing to a copy of the map. In the 1950s Jewish localities were circled on it in purple, while defeated or abandoned Arab villages were put in parentheses. The circle visualized belonging and at the same time differentiation: it was a boundary. It symbolizes both perpetuity and exclusivity. “The Zionist movement can be interpreted as a colonial movement,

” says Wachsmann, knowing well what a provocative effect this statement can have. She herself grew up in a village in Galilee on the border of Lebanon. There, pine forests planted by Jewish emigrants simulate a European landscape. Ruins of abandoned Arab villages left an imprint on Wachsmann’s childhood memories. Ever since she has lived in Berlin, she has looked back at her home country with greater detachment.

”Greetings From Namibia”

Shira Wachsmann has long since reflected on colonialism and displacement with eye towards the world beyond Israel as well. In the work she created for the Jewish Museum Berlin’s art vending machine, she deals with the genocide of the Herero people between 1904 and 1908. This destruction was the responsibility of the German Empire and marked a high point of colonial-imperialist aspirations to world power.

The condition of the material she engages with has also evolved: she began with charcoal, an archaic element and vestige of gatherings around a bonfire. Now she has turned to diamonds, a modification of carbon. She associates the colorless crystalline stone with the colonial exploitation of southwest Africa, present-day Namibia. “Liebe Grüße aus Namibia (Best wishes from Namibia),” Wachsmann handwrote on each postcard beneath the motif. Turning the card around, you can read on its back side a quote from then Secretary of State and later Chancellor of the Reich, Bernhard von Bülow (1848–1929): “We don’t wish to place anyone in the shade, but we too demand our place in the sun.” Inside the frame for a stamp in the upper right-hand corner, Wachsmann has a picture of a skull. The German Afrika-Corps used to send greetings via postcard to their faraway homes in the north. The colonial potentates conducted themselves like conquerors: their postcard pictures showed them with imprisoned Herero or even with skulls of the killed.

How Does it Correlate to Judaism?

Wachsmann consciously chose a theme for the art vending machine at the Jewish Museum that could perhaps not be directly linked to Judaism. “The Holocaust of European Jews overcasts all memory of other atrocities that have happened in history – particularly in Israel and Germany. Knowledge about the first genocide of the 20th century, in which 80% of the Herero and almost half of the Nama people were murdered, barely exists in German society.

” The genocide of the Herero was first officially recognized as such by the German federal government in the summer of 2015. German colonial history is still a side issue in German school books.

“The nice thing about the art vending machine is that you never know what you’ll get,

” says Wachsmann with a mischievous smile. She will soon be able to share the history of the Herero with unsuspecting museum visitors. “My postcards are lovely, at first glance. They look like they could be souvenirs.

” If you want to send one of them, first you have to stick a stamp over the skull: a reminder of the suppression of the genocide in Africa from Germany’s collective memory.

Saro Gorgis, Exhibitions

Shira Wachsmann (born in Tel Aviv, Israel, 1984), Liebe Grüße aus Namibia, Postcard, 2015; Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Jens Ziehe.

A Reminder in the Mail - the Nearly Forgotten Genocide of the Herero and Nama Peoples in Present-Day Namibia

The streets of Kreuzberg are soaked through with rain on this grey February day. Shira Wachsmann, a graceful young woman with short black hair, leads me into her atelier in a pre-war apartment. She doesn’t have much time. Her solo exhibition Tribe Fire was scheduled to open on 13 March 2016 in the gallery cubus-m in Berlin’s Schöneberg neighborhood. It remained there until 23 April 2016. Large drawings, soon to become part of the Tribe Fire installation, hang in the atelier. “There’s still a lot to do,

” the Israeli native explains.

Circled in, Cast out

One of her projects is spread across her desk: two postcards that Wachsmann designed for the Jewish Museum Berlin. She produced editions of 400 of each piece, which were available for individual purchase in 2016 in the art vending machine of the museum’s permanent exhibition. Wachsmann takes a seat in a green armchair and ponders the cards. They show two circular motifs, a form that appears throughout the artist’s work like a guiding principle. Here they depict an abstract diamond and a black sun.

“My pre-occupation with the circle motif started in 2012, when I found a map of Palestine from the period of the British Mandate in a second-hand bookshop in Israel,

” she recalls, pointing to a copy of the map. In the 1950s Jewish localities were circled on it in purple, while defeated or abandoned Arab villages were put in parentheses. The circle visualized belonging and at the same time differentiation: it was a boundary. It symbolizes both perpetuity and exclusivity. “The Zionist movement can be interpreted as a colonial movement,

” says Wachsmann, knowing well what a provocative effect this statement can have. She herself grew up in a village in Galilee on the border of Lebanon. There, pine forests planted by Jewish emigrants simulate a European landscape. Ruins of abandoned Arab villages left an imprint on Wachsmann’s childhood memories. Ever since she has lived in Berlin, she has looked back at her home country with greater detachment.

”Greetings From Namibia”

Shira Wachsmann has long since reflected on colonialism and displacement with eye towards the world beyond Israel as well. In the work she created for the Jewish Museum Berlin’s art vending machine, she deals with the genocide of the Herero people between 1904 and 1908. This destruction was the responsibility of the German Empire and marked a high point of colonial-imperialist aspirations to world power.

The condition of the material she engages with has also evolved: she began with charcoal, an archaic element and vestige of gatherings around a bonfire. Now she has turned to diamonds, a modification of carbon. She associates the colorless crystalline stone with the colonial exploitation of southwest Africa, present-day Namibia. “Liebe Grüße aus Namibia (Best wishes from Namibia),” Wachsmann handwrote on each postcard beneath the motif. Turning the card around, you can read on its back side a quote from then Secretary of State and later Chancellor of the Reich, Bernhard von Bülow (1848–1929): “We don’t wish to place anyone in the shade, but we too demand our place in the sun.” Inside the frame for a stamp in the upper right-hand corner, Wachsmann has a picture of a skull. The German Afrika-Corps used to send greetings via postcard to their faraway homes in the north. The colonial potentates conducted themselves like conquerors: their postcard pictures showed them with imprisoned Herero or even with skulls of the killed.

How Does it Correlate to Judaism?

Wachsmann consciously chose a theme for the art vending machine at the Jewish Museum that could perhaps not be directly linked to Judaism. “The Holocaust of European Jews overcasts all memory of other atrocities that have happened in history – particularly in Israel and Germany. Knowledge about the first genocide of the 20th century, in which 80% of the Herero and almost half of the Nama people were murdered, barely exists in German society.

” The genocide of the Herero was first officially recognized as such by the German federal government in the summer of 2015. German colonial history is still a side issue in German school books.

“The nice thing about the art vending machine is that you never know what you’ll get,

” says Wachsmann with a mischievous smile. She will soon be able to share the history of the Herero with unsuspecting museum visitors. “My postcards are lovely, at first glance. They look like they could be souvenirs.

” If you want to send one of them, first you have to stick a stamp over the skull: a reminder of the suppression of the genocide in Africa from Germany’s collective memory.

Saro Gorgis, Exhibitions

April–September 2015

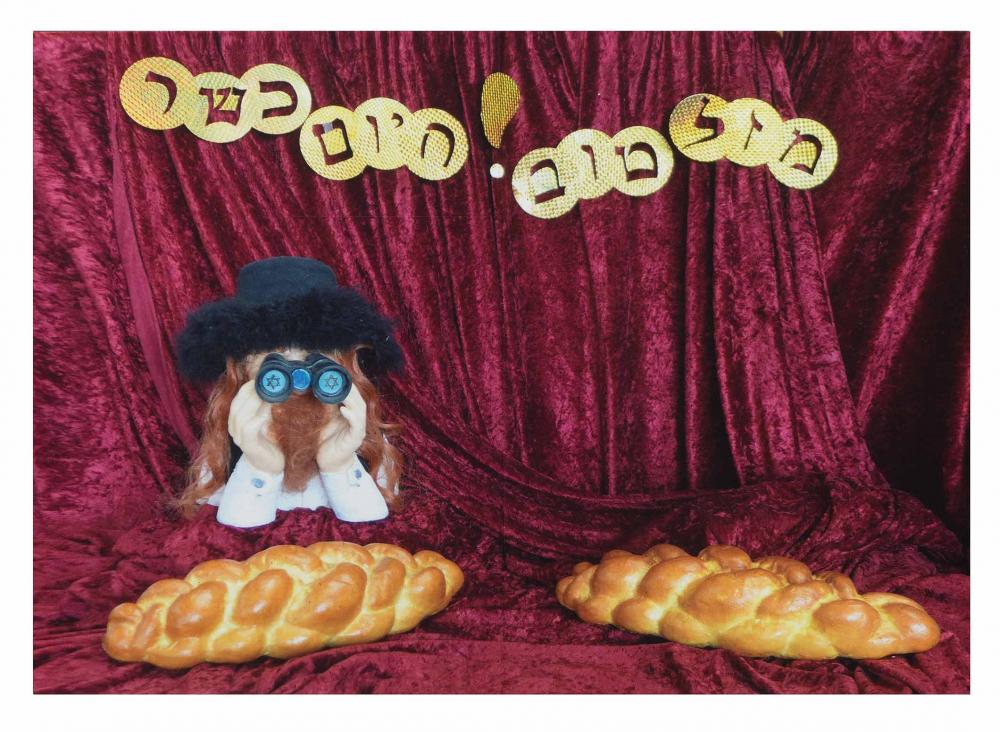

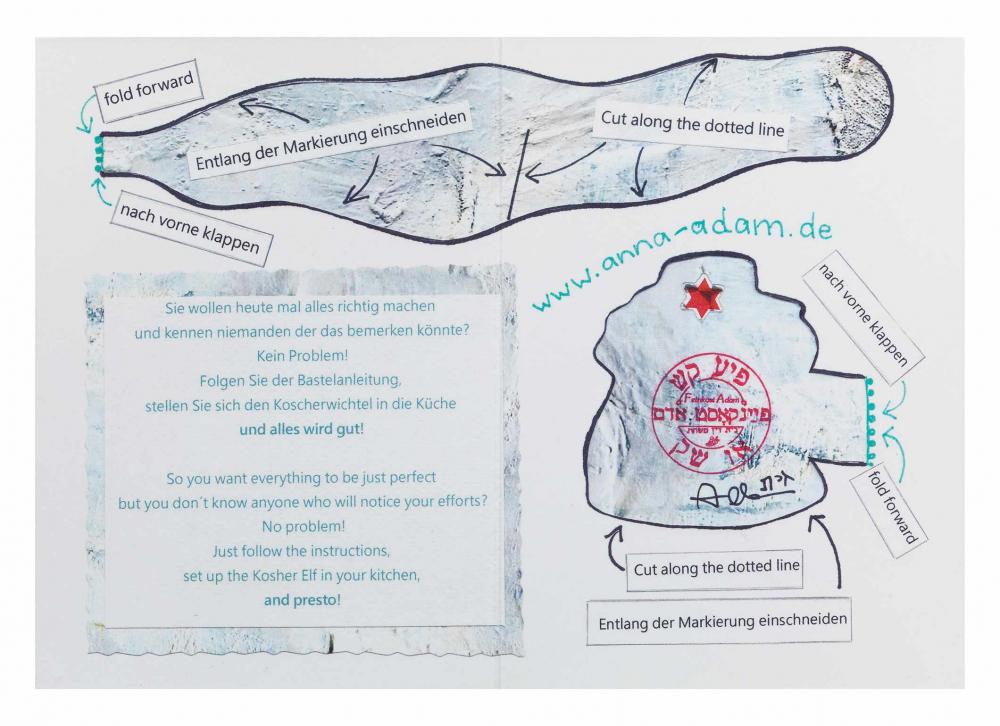

Anna Adam (born in Siegen, Germany, 1963), MAZEL TOV! Everything in your home is kosher today! ; Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Jens Ziehe.

A “kosher gnome” and everything’s ok? A conversation with Anna Adam

It’s not easy to find the way there. Good thing that the artist picked me up at the nearest subway station in Berlin’s Wedding district. Together we cross the courtyards of various businesses, pass a halal diner, climb a staircase, and suddenly we’re standing in front of the door of her atelier. Hardly has Anna opened it when I see the kosher gnome, observing the world through his binoculars.

It’s this figure that the artist reproduced in paper cut-out form on a card for our art vending machine: you cut the card and fold it to create a three-dimensional object. The instructions state that you should set him in your kitchen and then everything will be ok.

Gelia Eisert: Anna, what does the odd name kosher gnome mean? How do “kosher” and “gnome” even fit together? How will everything be ok? I’m confused.

Anna Adam: At home, a wichtel (in the original German) is an important little man. There are a lot of these “important men”. My “kosher gnome” was born in 2002. He’s definitely supposed to be confusing. “Kosher” and “gnome” fit together because I committed myself to the task of “healing the German-Jewish sickness”, as I call it. To that end I work with satirical means, which – unlike comedy – take everyday politics as a starting point.

Gelia Eisert: You mentioned the year it was born. What were the circumstances of the kosher gnome‘s birth?

Anna Adam: At that time I had started a delicatessen (Feinkostladen) for the Jewish Museum at Franken in Fürth. When people asked if I was serving “heavy food” (schwere Kost), I would tell them, “Oh no, it’s fine food” (Feinkost). Thus came into being “Fine-Food Adam ©”. I had also created some art objects for the museum that you could search for in the exhibition with the help of a kind of treasure map. There were satirical texts as well, that complemented the installation. This is an object from the exhibition, my book Jewish Breathing: an introduction to exhaled happiness. The accompanying beverage Fallowblossom Rose of Jericho, which supported “inner opening”, is unfortunately all gone – it was really good.

I flip through the pages of the book, observing the dramaturgical escalation: approaching the “Jewish soul” through “Jewish breathing.” I can’t help blurting out, But Anna, this is absurd!

Anna Adam: At exhibitions by the Jewish artists’ group “Meshulash” (Hebrew for ‘triangle’), to which I belonged, I would hear comments from dedicated ‘semitophiles’ like “the Jewish people are just so different”. The drawings for the book emerged impromptu, after that experience.

Gelia Eisert: Although this all appears light and ironic, the delicatessen in Fürth was anything but delicate for the public, the press, and the Jewish community. You were even called an anti-Semite.

Anna Adam: That complaint proved itself absurd and it was thrown out. Satire was very unfamiliar territory in that context and even Jews projected everything imaginable onto it. The press were tripping over themselves. It was the birthing hour of my kosher gnome. I got the advice to marry a good religious man, and then you’ll settle down and won’t need to do things like this

. I took a deep breath and answered: Darling. Women like me don’t need to marry a man like that, we just build him.

And that’s what I did. And look, here he is: he’s perfect, he’s smaller than I am, petite like Napoleon, keeps his mouth shut, and makes sure that everything is kosher.

Gelia Eisert: You and your gnome are nearly inseparable. I saw that he is even with you on the Happy Hippy Jew Bus on tours through Germany.

Anna Adam: The person who is really always with me is my life partner Jalda Rebling, a musician and Jewish cantor. We tour with the “BEA” – that’s what our current bus is called – and look for pedestrian areas and schools, where we can work to soften clichés and prejudices through satirical means. The bus is designed à la ‘peace and love with a German car’ so that people cannot stay so serious or afflicted about the subject of Judaism. Some funny things are housed in the bus, things that explain a lot. We’ve been going on these tours since 2011, at first with “BEN” but, sadly, the German Association for Technical Inspection took him away from us.

Gelia Eisert, Exhibitions

Anna Adam (born in Siegen, Germany, 1963), MAZEL TOV! Everything in your home is kosher today! ; Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Jens Ziehe.

A “kosher gnome” and everything’s ok? A conversation with Anna Adam

It’s not easy to find the way there. Good thing that the artist picked me up at the nearest subway station in Berlin’s Wedding district. Together we cross the courtyards of various businesses, pass a halal diner, climb a staircase, and suddenly we’re standing in front of the door of her atelier. Hardly has Anna opened it when I see the kosher gnome, observing the world through his binoculars.

It’s this figure that the artist reproduced in paper cut-out form on a card for our art vending machine: you cut the card and fold it to create a three-dimensional object. The instructions state that you should set him in your kitchen and then everything will be ok.

Gelia Eisert: Anna, what does the odd name kosher gnome mean? How do “kosher” and “gnome” even fit together? How will everything be ok? I’m confused.

Anna Adam: At home, a wichtel (in the original German) is an important little man. There are a lot of these “important men”. My “kosher gnome” was born in 2002. He’s definitely supposed to be confusing. “Kosher” and “gnome” fit together because I committed myself to the task of “healing the German-Jewish sickness”, as I call it. To that end I work with satirical means, which – unlike comedy – take everyday politics as a starting point.

Gelia Eisert: You mentioned the year it was born. What were the circumstances of the kosher gnome‘s birth?

Anna Adam: At that time I had started a delicatessen (Feinkostladen) for the Jewish Museum at Franken in Fürth. When people asked if I was serving “heavy food” (schwere Kost), I would tell them, “Oh no, it’s fine food” (Feinkost). Thus came into being “Fine-Food Adam ©”. I had also created some art objects for the museum that you could search for in the exhibition with the help of a kind of treasure map. There were satirical texts as well, that complemented the installation. This is an object from the exhibition, my book Jewish Breathing: an introduction to exhaled happiness. The accompanying beverage Fallowblossom Rose of Jericho, which supported “inner opening”, is unfortunately all gone – it was really good.

I flip through the pages of the book, observing the dramaturgical escalation: approaching the “Jewish soul” through “Jewish breathing.” I can’t help blurting out, But Anna, this is absurd!

Anna Adam: At exhibitions by the Jewish artists’ group “Meshulash” (Hebrew for ‘triangle’), to which I belonged, I would hear comments from dedicated ‘semitophiles’ like “the Jewish people are just so different”. The drawings for the book emerged impromptu, after that experience.

Gelia Eisert: Although this all appears light and ironic, the delicatessen in Fürth was anything but delicate for the public, the press, and the Jewish community. You were even called an anti-Semite.

Anna Adam: That complaint proved itself absurd and it was thrown out. Satire was very unfamiliar territory in that context and even Jews projected everything imaginable onto it. The press were tripping over themselves. It was the birthing hour of my kosher gnome. I got the advice to marry a good religious man, and then you’ll settle down and won’t need to do things like this

. I took a deep breath and answered: Darling. Women like me don’t need to marry a man like that, we just build him.

And that’s what I did. And look, here he is: he’s perfect, he’s smaller than I am, petite like Napoleon, keeps his mouth shut, and makes sure that everything is kosher.

Gelia Eisert: You and your gnome are nearly inseparable. I saw that he is even with you on the Happy Hippy Jew Bus on tours through Germany.

Anna Adam: The person who is really always with me is my life partner Jalda Rebling, a musician and Jewish cantor. We tour with the “BEA” – that’s what our current bus is called – and look for pedestrian areas and schools, where we can work to soften clichés and prejudices through satirical means. The bus is designed à la ‘peace and love with a German car’ so that people cannot stay so serious or afflicted about the subject of Judaism. Some funny things are housed in the bus, things that explain a lot. We’ve been going on these tours since 2011, at first with “BEN” but, sadly, the German Association for Technical Inspection took him away from us.

Gelia Eisert, Exhibitions

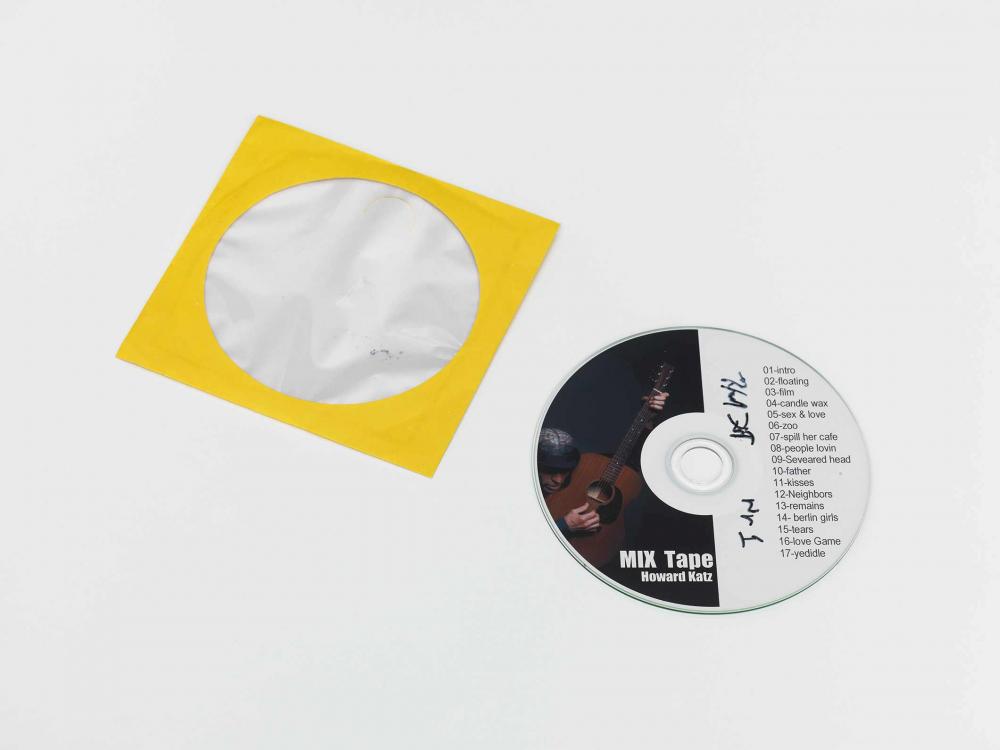

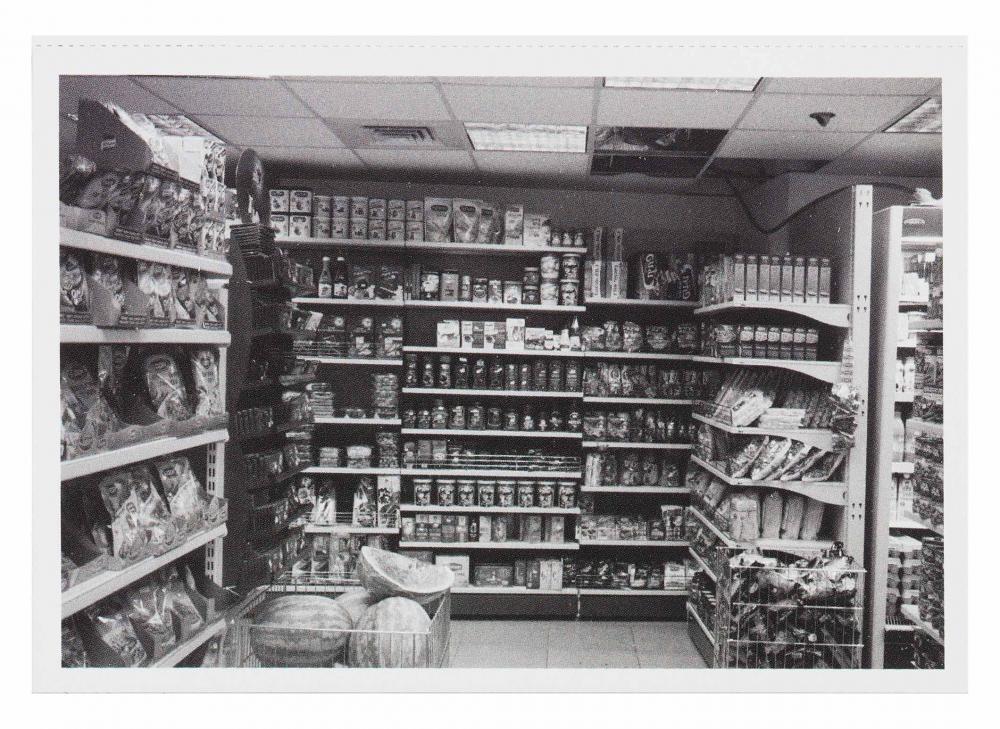

Howard Katz (born in New York, USA), MIX Tape, 2014; Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Jens Ziehe.

Energy galore: encountering Howard Katz

It always goes by so quickly: in summer 2015, it felt as if the third round of the art vending machine in the Jewish Museum Berlin’s permanent exhibition had just started. But in fact it was already almost finished and sold out – 2,600 works! That was certainly enough reason to pop by to visit Howard Katz and ask him some questions, especially considering that he had been the first of the at the time 22 artists we’d featured to use music…

Dagmar Ganßloser: Howard, you work as an artist in many different genres. You’re a dancer, performer, and choreographer, but you’re also an active visual artist, and on top of that a singer-songwriter. Right now the art vending machine has your Mix Tape as well as 4 short films. How did you choose those?

Howard Katz: It was clear to me from the start that I wanted to present my music in the art vending machine. The 17 songs on Mix Tape came into being over the last twenty years plus and – the same as 4 short films – they’re mainly about experiences I’ve had since I’ve lived in Berlin, so since the mid-1990s. The production was uncomplicated and I made the selection intuitively, from the heart. I made the four videos for my songs completely on my own, with my telephone – it was an opportunity to try out something new.

Dagmar Ganßloser: On Mix Tape you talk directly to your potential listeners, asking them for feedback on your youtube channel and you categorize your manner as a “very Jewish way of storytelling”. What do you mean by that?

Howard Katz: I grew up in New York and as a Jew I belonged to one of many minorities, which was anything but conflict-free. When I came here I became much more conscious of being Jewish. My work was rejected a few times because it’s too personal and too emotional. One woman told me, It’s a bit embarrassing because it’s so emotional. We need distance.

For me, Jewish means: we’re pretty close to each other, sometimes it hurts, sometimes it sticks, sometimes there’s friction.

Dagmar Ganßloser: How long have you been writing songs?

Howard Katz: I wrote my first songs when I was 12 or 13. I still find the music I wrote back then charming and lovely, but it wasn’t until I was in my mid-40s that I really found my voice. I also write songs in German, by the way…

Dagmar Ganßloser: Along with dance and music you also do bodywork. Have you been doing that a long time?

Howard Katz: I’ve been interested in people since I was little and I always saw immediately if something in the quality of their movements or emotions was interesting. That’s my talent. So I always wanted to work with people, that was quite clear. When I was eight, I tried to talk my parents into letting me learn dance, but they didn’t allow it. I then waited a long time – another eight years! – but finally I began (he laughs): I moved out when I was 16, started my dance training, worked on the side, and at 17 I already had my own practice in a New York dance studio doing reflexology and other massage techniques.

Dagmar Ganßloser: What really struck me about the amplitude of your work is that there’s a huge range and yet it all reveals your particular ‘handwriting’. That’s not just true of your music but also your choreography. For instance, with Kata. And it’s also clear in the movement system that you developed, “5qualities”.

Howard Katz: My handwriting is always clearly visible. I can’t say exactly why that’s the case. Other people do exactly the same thing but you don’t see that it’s them, whereas in my work you always see it’s mine. My artistic and my therapeutic work are really one entity for me.

Dagmar Ganßloser: What is “5qualities” actually about? Are you trying to communicate a style of movement or is it something more?

Howard Katz: It began with my search for a system of movement that everyone could learn. Of course I started with many more qualities, with 122! But eventually I noticed that there are only five: carry, fall, flow, throw, put – the rest are really a mix of these five basic qualities. I found these five qualities in every style of dance and in every type of martial art as well. “5qualities” as a technique can help people to find their equilibrium and it can thus support the process of self-discovery or personal development. So, I’m not healing, it’s more about encouraging self-help.

Dagmar Ganßloser: What are you working on at the moment?

Howard Katz: My wife, Liz Williams, and I did our first cabaret show at the end of June, NOIR, MusicCircusTheater, with Berlin’s best artistes. They’re really fantastic! We’re doing some genuinely dangerous acts in the air. I’ve been learning this in the last few years and have gotten quite good. I made the music for NOIR as well, together with my band PostHolocaustPop – here under the name PostTraumaticPop. And we’ve started a company with the artistes so we’re going to keep doing more.

Dagmar Ganßloser, Digital & Publishing

Howard Katz (born in New York, USA), 4 Short Films, 2015; Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Jens Ziehe.

Energy galore: encountering Howard Katz

It always goes by so quickly: in summer 2015, it felt as if the third round of the art vending machine in the Jewish Museum Berlin’s permanent exhibition had just started. But in fact it was already almost finished and sold out – 2,600 works! That was certainly enough reason to pop by to visit Howard Katz and ask him some questions, especially considering that he had been the first of the at the time 22 artists we’d featured to use music…

Dagmar Ganßloser: Howard, you work as an artist in many different genres. You’re a dancer, performer, and choreographer, but you’re also an active visual artist, and on top of that a singer-songwriter. Right now the art vending machine has your Mix Tape as well as 4 short films. How did you choose those?

Howard Katz: It was clear to me from the start that I wanted to present my music in the art vending machine. The 17 songs on Mix Tape came into being over the last twenty years plus and – the same as 4 short films – they’re mainly about experiences I’ve had since I’ve lived in Berlin, so since the mid-1990s. The production was uncomplicated and I made the selection intuitively, from the heart. I made the four videos for my songs completely on my own, with my telephone – it was an opportunity to try out something new.

Dagmar Ganßloser: On Mix Tape you talk directly to your potential listeners, asking them for feedback on your youtube channel and you categorize your manner as a “very Jewish way of storytelling”. What do you mean by that?

Howard Katz: I grew up in New York and as a Jew I belonged to one of many minorities, which was anything but conflict-free. When I came here I became much more conscious of being Jewish. My work was rejected a few times because it’s too personal and too emotional. One woman told me, It’s a bit embarrassing because it’s so emotional. We need distance.

For me, Jewish means: we’re pretty close to each other, sometimes it hurts, sometimes it sticks, sometimes there’s friction.

Dagmar Ganßloser: How long have you been writing songs?

Howard Katz: I wrote my first songs when I was 12 or 13. I still find the music I wrote back then charming and lovely, but it wasn’t until I was in my mid-40s that I really found my voice. I also write songs in German, by the way…

Dagmar Ganßloser: Along with dance and music you also do bodywork. Have you been doing that a long time?

Howard Katz: I’ve been interested in people since I was little and I always saw immediately if something in the quality of their movements or emotions was interesting. That’s my talent. So I always wanted to work with people, that was quite clear. When I was eight, I tried to talk my parents into letting me learn dance, but they didn’t allow it. I then waited a long time – another eight years! – but finally I began (he laughs): I moved out when I was 16, started my dance training, worked on the side, and at 17 I already had my own practice in a New York dance studio doing reflexology and other massage techniques.

Dagmar Ganßloser: What really struck me about the amplitude of your work is that there’s a huge range and yet it all reveals your particular ‘handwriting’. That’s not just true of your music but also your choreography. For instance, with Kata. And it’s also clear in the movement system that you developed, “5qualities”.

Howard Katz: My handwriting is always clearly visible. I can’t say exactly why that’s the case. Other people do exactly the same thing but you don’t see that it’s them, whereas in my work you always see it’s mine. My artistic and my therapeutic work are really one entity for me.

Dagmar Ganßloser: What is “5qualities” actually about? Are you trying to communicate a style of movement or is it something more?

Howard Katz: It began with my search for a system of movement that everyone could learn. Of course I started with many more qualities, with 122! But eventually I noticed that there are only five: carry, fall, flow, throw, put – the rest are really a mix of these five basic qualities. I found these five qualities in every style of dance and in every type of martial art as well. “5qualities” as a technique can help people to find their equilibrium and it can thus support the process of self-discovery or personal development. So, I’m not healing, it’s more about encouraging self-help.

Dagmar Ganßloser: What are you working on at the moment?