A Kind of Family Gathering

Bitter Herbs and Their Relatives in the Diaspora Garden

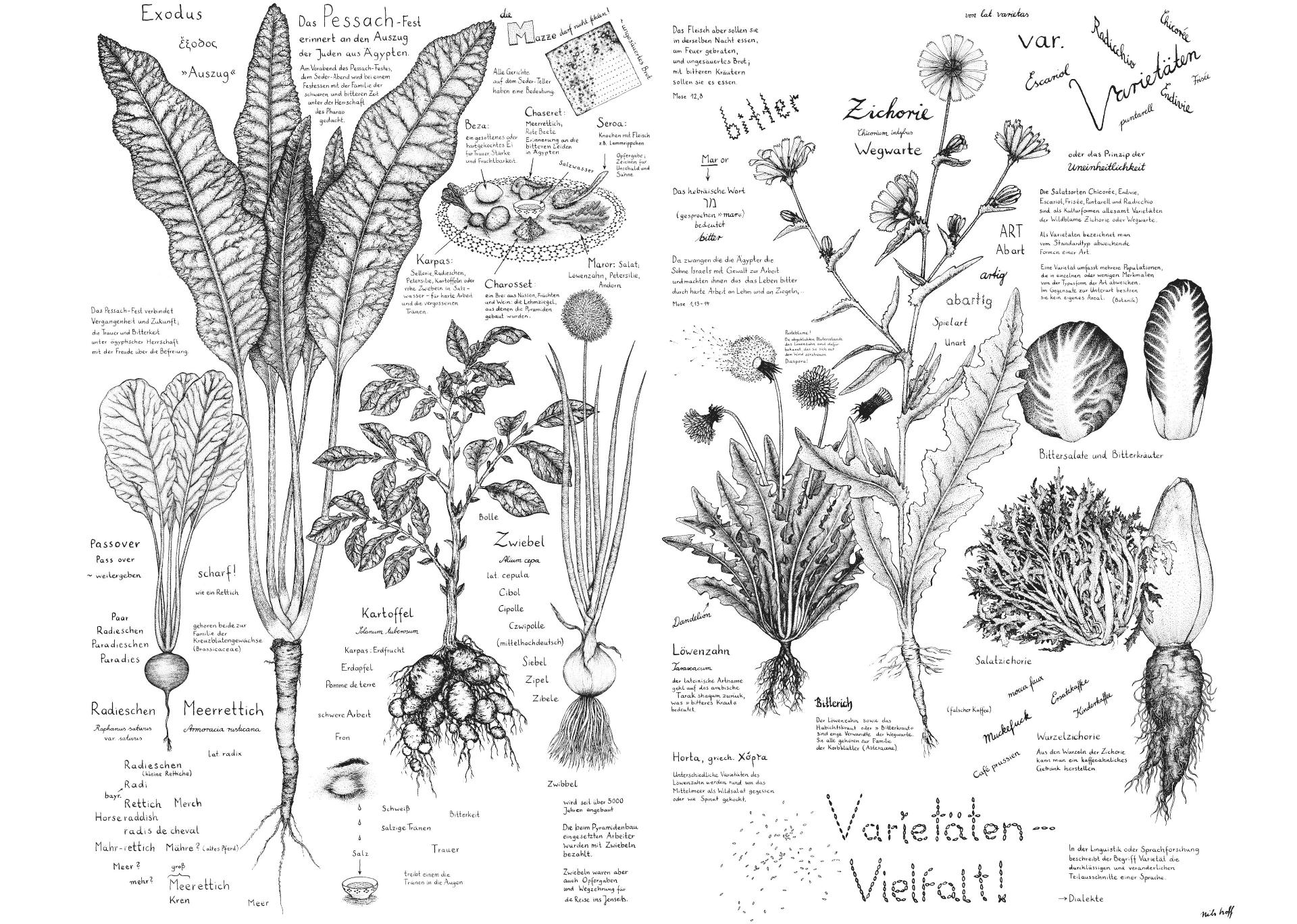

Illustration of the bitter herbs; Jewish Museum Berlin, illustration: Nils Hoff, 2017

It’s Seder and the family is getting together. Some are traveling from farther away, others are flourishing right here. At the table are escarole, lettuce, parsley, kohlrabi, Belgian endive, and dandelion. But what about horseradish and red radish? They’re both late this year.

The story of the plants and their fruits that have particular meaning on the Seder plate at Passover could be told in various similar ways. They all grow in the Diaspora Garden, which you can visit inside the W. Michael Blumenthal Academy at the Jewish Museum. It features a kind of green sculpture by the landscape architects le balto that came into being through a collaboration with the museum, particularly with our education department. As a botanist and the officially-designated garden guardian I make my rounds through all four long plateaux of beds, plucking a brown leaflet here, bending new shoots in the right direction there. I enjoy the strawberry’s first leaves and check to see which of the bitter plants made it through the winter. The horehound didn’t survive so I’ll be asking the gardeners to plant a new one.

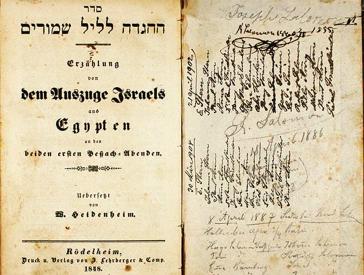

X

X

Shlomit Tulgan made this Seder plate from clay for our children’s exhibition on Passover; Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Jens Ziehe.

During our 2016 school holiday program the children used the Diaspora Garden too; Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Tanja Petersen

Bitter herbs make a double appearance on the Seder plate, since the commemoration of slavery in Egypt and the bitterness connected with it is an important narrative. Three different seasonal holidays — Passover, the Feast of Weeks (Shavuot), and the Feast of Tabernacles (Sukkot) — recall the exodus from Egypt, the transmission of the commandments, and the years of wandering in the wilderness. From the beginning of their existence Jews have been dealing with a life between the poles of diaspora and homeland. Thus since time immemorial, the Jewish community has been grappling with the question of how, in the diaspora, to substitute accustomed but often unobtainable foods and ritual dishes with available options — and so to extend and update these traditions.

The Mishnah cites five bitter herbs: Romaine lettuce, thistle, what’s known as endive or chicory, eryngo, and other “salads.” The leaves are supposed to be enjoyed fresh or wilted, but shouldn’t date back to the previous year. Another translation calls them the “vegetables with which people fulfill their Passover obligation: lettuce, endive, chervil, eryngo, and oxtongue” (from Die Mischna. Festzeiten Seder Mo’ed, translated and edited by Michael Krupp).

Horseradish isn’t mentioned here. It belongs, together with other well-known salad leaves like arugula and mustard, to the crucifers, while most of the others mentioned in the Mishnah (eryngo, chicory, thistle, and dandelion) are asters or “composites” — part of the Asteraceae family. It gets even more confusing when you consider that horseradish (Armoracia rusticana) actually belongs to the extended family of crucifers, but isn’t closely related to the other types of radish, of the genus Raphanus, like the little red radish for instance. At Passover, it’s a bit more like a brother-in-law who married into the family.

How did horseradish get onto the Seder plate? After all, it’s not bitter, it’s hot. In fact it didn’t always belong with the chosen dishes of the Seder. It has, however, been a part of the story of Ashkenazi Judaism since the Middle Ages. In Hebrew the word maror is often there on the Seder plate, though maror (bitter) can indicate horseradish or watercress. The second symbolic food, chazeret, is represented by another bitter herb.

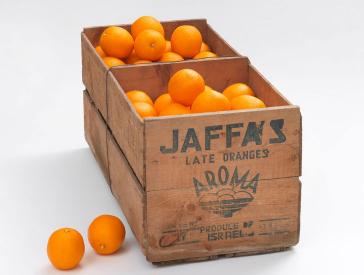

Radish was first mentioned in the rabbinical literature in the middle of the 12th century and its use discussed by scholars for two hundred years. The history of horseradish on the Seder plate and its authorization as one of the five bitter herbs specified by the Mishnah reflects Jews’ mobility and the founding of growing Jewish communities in the Western and Eastern European diaspora between the 12th and 18th centuries. For the prescribed plants were often simply unavailable or the consumption of fresh, new leaves ever less likely, the further one went into the climatic Northeast. Gardens and whole landscapes were still covered with snow at Passover.

The Seder plate with its contents, with what it’s currently allowed to feature and the newly added symbolic dishes or species, demonstrates the complexity and long historical development of this holiday. With its particular pungency, horseradish and its symbolic meaning don’t just recall the bitterness of slavery and forced migration. It is also, itself, a symbolic product of this history of migration.

Today there’s much that is no longer bitter, since centuries of cultivation have bred out the bitter compounds. Those who really want to taste the bitter flavor could consider tasting the crop from the Diaspora Garden. Due to the unnatural conditions of the location and the lack of sun, even the off-the-shelf varieties available here are woody and bitter — nearly inedible.

Regardless of the actual selection of bitter herbs for Seder this year, it will surely be a wonderful holiday with kith and kin.

Chag Pessach Sameach 5777!

Tanja Petersen studied history and biology. She has been conveying complex content and cultural subjects to Jewish Museum Berlin visitors for over 15 years.

X

X

Visitors in the Diaspora Garden on the 2015 Open Day at the Academy; Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Hanna Wolf

Citation recommendation:

Tanja Petersen (2017), A Kind of Family Gathering . Bitter Herbs and Their Relatives in the Diaspora Garden .

URL: www.jmberlin.de/en/node/7471

Holidays: Old Rituals, New Customs (19)