Diagonal Line of Diversity

The Lindenstrasse in Berlin, Caught Between Past and Future

Stephan Becker

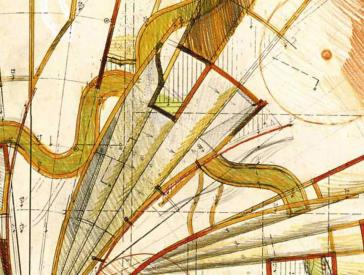

When the first trade union building was built in imperial Berlin around 1900, the labor movement was still considered a “danger to the public safety.” The building still stands in Engeldamm in Luisenstadt, the part of the district of Kreuzberg that begins just behind the Jewish Museum Berlin. The building was financed by Leo Arons, a successful scholar, pioneer of social democracy, and son of an upper-class Jewish family. Arons brought together many lines of historical development that continue to shape the area today, and that can be experienced spatially just in front of the Jewish Museum Berlin, which holds his papers. Indeed, the diagonal course of Lindenstrasse resulted from the convergence of the prestigious quarter of Friedrichstadt (marked by a rigid north-south orientation), and the disorderly Luisenstadt to the east (where working-class housing was built, often in an informal style), along the street to Köpenick in the southeast. This interface not only symbolizes the area’s past but will also determine its future. More on this later.

Middle Classes Contrast With Working Classes

Beginning in 1688, the center of Berlin was significantly expanded with the addition of the Friedrichstadt quarter. The strict regulation of building activity was the result not only of the king’s baroque aesthetic program, but also of the fact that the settlement was promoted by the state. It was also built specifically for aristocratic and wealthy residents in addition to French religious refugees. Impressive urban spaces emerged at the gates of the Berlin Customs Wall: the square at Pariser Platz; the octagon at Leipziger Platz; the circle at present-day Mehringplatz. The planners deliberately added decorative edifices, such as the old building of the Jewish Museum Berlin, which from 1735 onward housed various legal institutions. Formally a part of Luisenstadt, this building was conceived as a visual anchor at the end of Markgrafenstrasse, as seen from the Gendarmenmarkt looking south.

By contrast, the adjacent Luisenstadt was developed mainly at the initiative of small-scale tradespeople who were given the freedom to build as they pleased. Poor job-seeking immigrants found a home here as well. With the transformation of Berlin in the Wilhelmine era, its districts grew more similar in appearance, but the social differences remained: the middle classes, government authorities, and commercial enterprises in Friedrichstadt contrasted with the working classes, courtyard factories, and home workers in Luisenstadt. At the same time, connective spaces emerged. Hallesches Tor became an important transport hub; Friedrichstrasse was transformed into a business and entertainment quarter; a newspaper district was established in Berlin that is recalled today by the Springer tower, and the headquarters of the Tageszeitung (taz) newspaper across the way.

From Newspaper District into a Neighborhood of Internet Companies?

The left-wing taz and the large Springer media group are not only the vestiges of a bygone era, but continue to shape the area today. Springer is planning a digital hub at the northern end of Lindenstrasse: a huge building designed by Rem Koolhaas in which all its online activities are to be combined. And the taz is planning a new headquarters in nearby Friedrichstrasse, yet another project testifying to a company’s successful adaptation to present requirements. With the GSW tower on Rudi-Dutschke-Strasse, which will be occupied by a large startup, the newspaper district is rapidly evolving into a neighborhood of Internet companies.

The new taz headquarters is part of a construction project that could point the way forward not only for the district, but also for the entire city. Thanks to a local initiative, a new quarter is emerging directly opposite the Jewish Museum that points to a shift in political paradigms. The site was once home to a centrally located wholesale flower market. The old market hall was remodeled by Daniel Libeskind, and now houses the W. Michael Blumenthal Academy. Instead of selling the rest of the lot to the investor who made the highest bid, the city-owned company in charge of the market opted for an alternative tender procedure that gave special consideration to projects with a good mix of social and creative functions. This is why a lively neighborhood is likely to emerge here in the future. In other words, experimentation triumphed over speculation. That the new residents happen to include one of Leo Arons’ great grandsons is not only an interesting twist, but reveals much about the district’s recent history.

"Kreuzberg Mix"

Architect and bar owner Julian Arons lives and works in the eastern part of Luisenstadt, where a new Kreuzberger Mischung (“Kreuzberg mix”) of migrant life and alternative culture has evolved since the 1970s. This term was coined by city planners to resurrect the historical mix of functions that was typical of Kreuzberg in the Wilhelmine era. The city originally planned to demolish an entire neighborhood of old buildings in order to construct a highway that would have run across what today are the grounds of the Jewish Museum Berlin. However, the project was successfully blocked by protestors. The vacant buildings were occupied by squatters and various social biotopes emerged that continue to influence the character of the neighborhood today. These housing and lifestyle experiments from the past can be seen as forerunners of projects like the one at the former wholesale flower market. Within the framework of the 1987 International Building Exhibition (IBA), preparations for which began in 1979, ideas like these caught on in official policies. Thus, to the north of the Jewish Museum Berlin, between Lindenstrasse, Oranienstrasse, and Alte Jakobstrasse, many residential buildings were constructed that broke with the paradigm of a car-friendly, less densely built city that had been followed since the end of the war. In line with the idea of a critical reconstruction, historical streetscapes were supplemented with understated contemporary architecture. New types of buildings such as the “urban villa”—a freestanding multifamily structure—rounded off the architectural offerings that were intended to attract people, and especially families, back to the city.

The many open spaces around the Jewish Museum are a consequence of the war. Due to its proximity to the government district, the southern part of Friedrichstadt was heavily damaged by air raids. Densely developed city blocks were reduced to urban voids more reminiscent of the city periphery than the city center. However, the flower market, with its huge parking lots and turning areas, was not located on a bombedout site. A large indoor market had been constructed on the site in the nineteenth century in order to sell the food that was delivered to the city via the Hallesches Tor.

The Rise of Modernitiy

In terms of its functionality, the area surrounding the Jewish Museum Berlin was always more diverse than the average city district. This is still evident today in the former Imperial Patent Office and the House of the German Metal Workers’ Union. It was not until the 1950s and 1960s that the leap in scale from individual plot to entire city block became the norm for urban planners. With the rise of modernity, streets were no longer constructed house by house by individual builders. Rather, larger areas were developed uniformly by housing associations. One example is the Spring development east of the Jewish Museum, which was completed in 1962 and named after its American backers. In the period to 1974, the circle at Hallesches Tor was rebuilt to plans by Hans Scharoun and later by Werner Düttmann. In the process the former Belle-Alliance-Platz, renamed Mehringplatz, was completely redesigned with an impressive high rise complex.

In the Shadow of the Berlin Wall

It is precisely the loose arrangement of these architectural fragments of modernity that the IBA planners felt needed to be fought, not only ideologically, but also in terms of their spatial characteristics. The goal was to eliminate emptiness and openness, which is why a dense perimeter block development was planned for the remaining vacant lots. But even the proponents of a comprehensive urban renewal could not entirely resist the special atmosphere that still prevailed in the area in the mid-1980s. Situated in the shadow of the Berlin Wall, a strangely provisional cityscape flourished, consisting of historical legacies, the enchanted wastelands of war, and imposing new towers whose utopian elements had long given way to dystopian connotations. This state of affairs vanished with the last vacant lots, but unusual open spaces and passages emerged as domesticated variations in their place, such as the Theodor Wolff Park and the E.T.A.-Hoffmann-Promenade at the southern end of Friedrichstrasse. With their stone steps, low walls, and austere arcades, they recall Greek and Italian ruins and even today open up views of back courtyards and firewalls.

Due to this systematic layering of old and new, the area is a good example of how twentieth-century architectural dogmas can be overcome. Fittingly, the new quarter at the former wholesale flower market defies clear categorization, not only in terms of its spatial configuration, which creates a field of cross-period tensions, but also in terms of its use. After all, in addition to apartments, commercial spaces, and studios, it will offer project spaces and cultural activities for the entire neighborhood.

A Place of Dialog

The responsible parties hope for a place of dialog, which is in fact urgently needed. The district currently resembles an archipelago of autonomous city fragments, and the residents—separated by wide streets and green parks—mostly keep to themselves. Certainly, such an urban structure ensures diversity, but this diversity only grows fecund when people become better acquainted. If the plans are successful, they will revive old traditions. From its beginnings, the Lindenstrasse was a place where very different life-worlds collided—which is why the street, with its diagonal orientation, can be understood as important symbol of diversity today.

The Author

Stephan Becker, born 1978 in Rheinfelden, studied architecture in Berlin, specializing on the topic of cities and architectural theory. After having worked as an architect, he today focuses on publications, exhibitions and urbanistic initiatives. His articles have been published with various newspapers and magazines. Since 2013 he is an architectural editor at BauNetz.

Citation recommendation:

Stephan Becker (2016), Diagonal Line of Diversity. The Lindenstrasse in Berlin, Caught Between Past and Future.

URL: www.jmberlin.de/en/node/3980