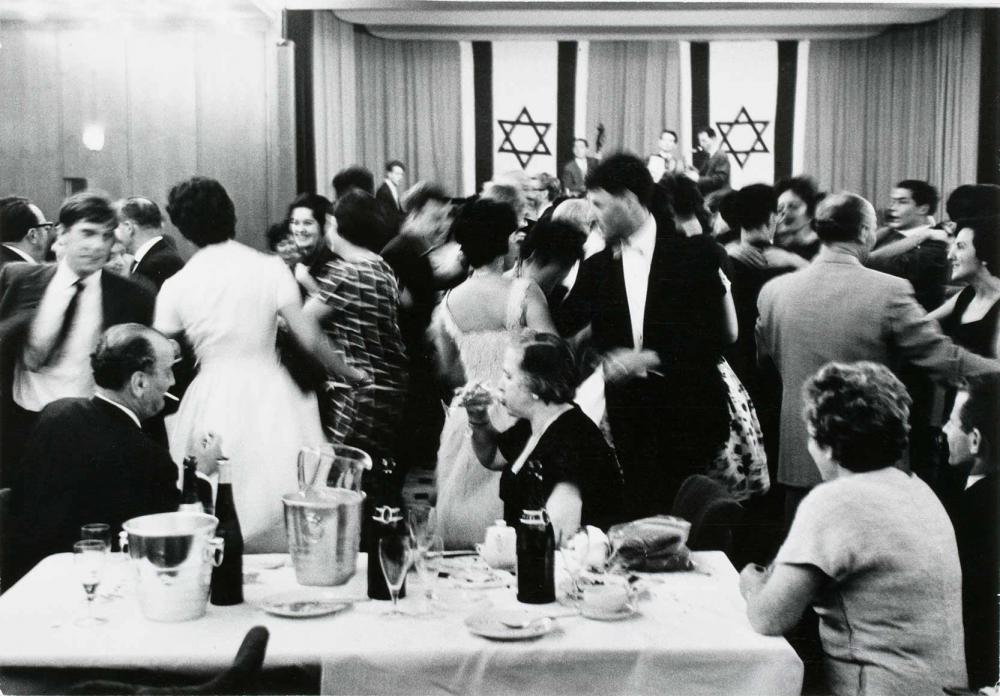

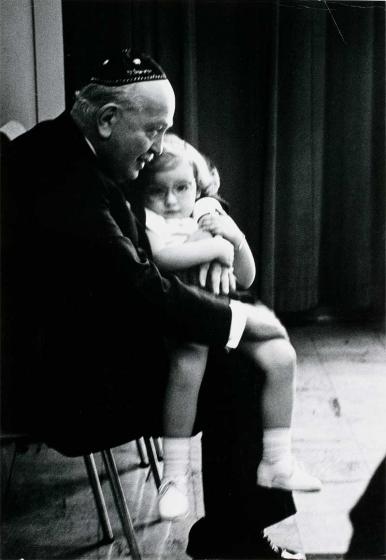

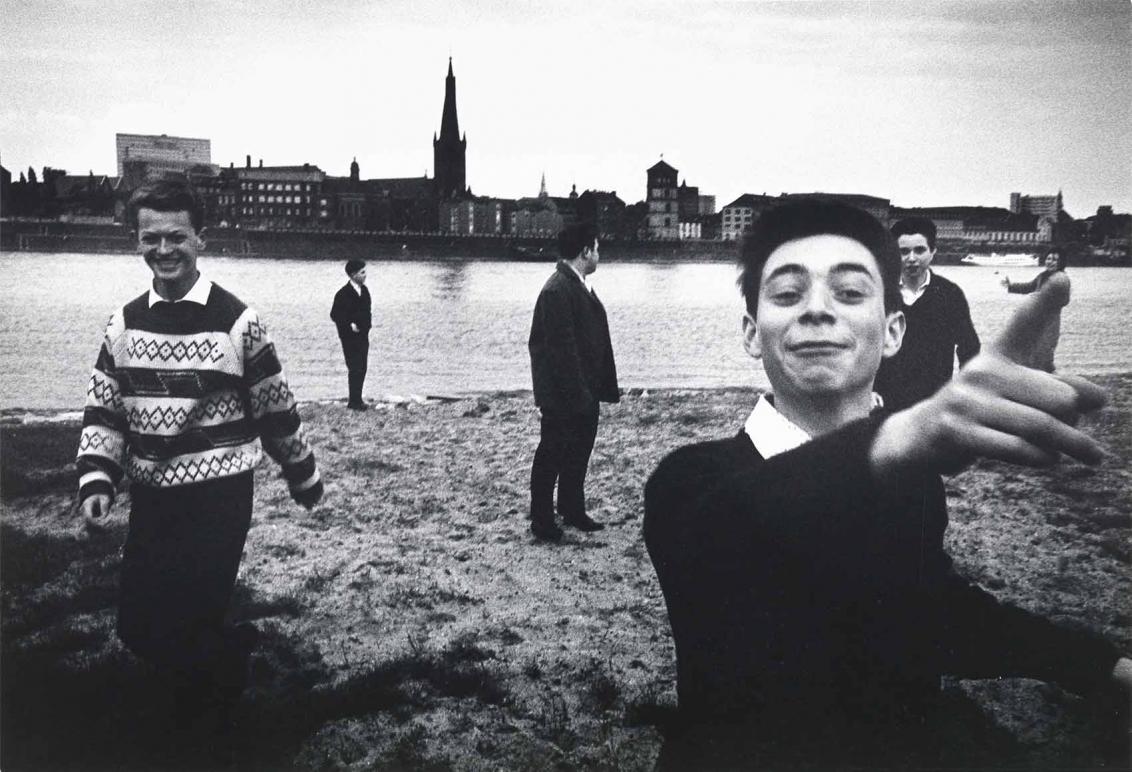

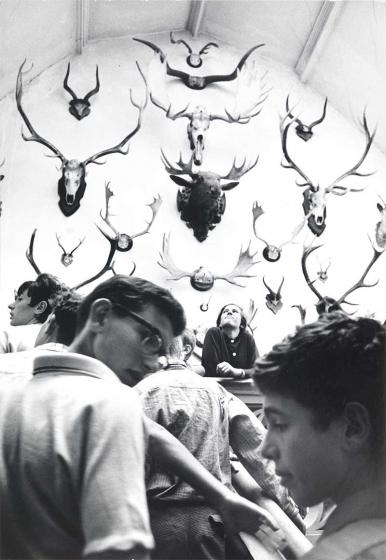

Leonard Freed, Simhat Torah ball, Köln, 1961; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2006/198/8

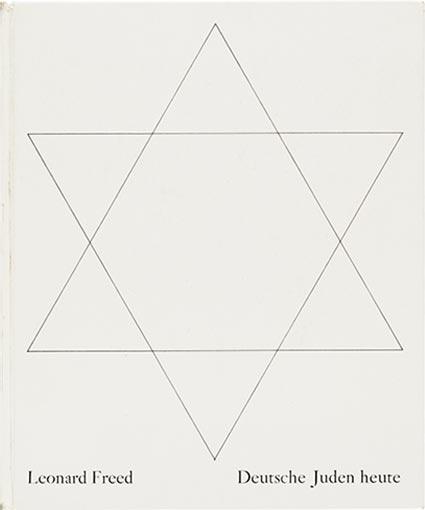

German Jews Today

Leonard Freed

At the start of the 1960s, not even 20 years after the abyss of the Holocaust, the American-Jewish photographer Leonard Freed (1929‒2006) spent several months traveling through West Germany. He wanted to use his camera to capture how German Jews were currently living. Through his images, Freed set out to counteract the Germans’ ignorance of the invisible Jewish minority living among them. He took photographs in several Jewish communities, especially in the areas around Frankfurt and Düsseldorf.

11 Nov 2024 to 27 Apr 2025

Where

Libeskind Building, ground level, Eric F. Ross Gallery

Lindenstraße 9–14, 10969 Berlin

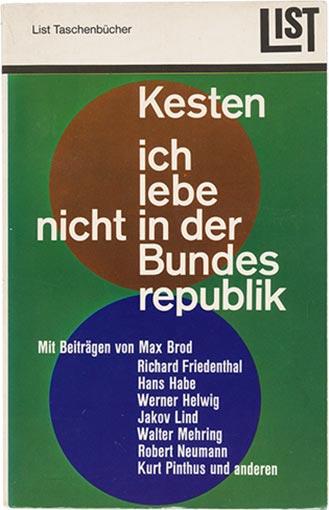

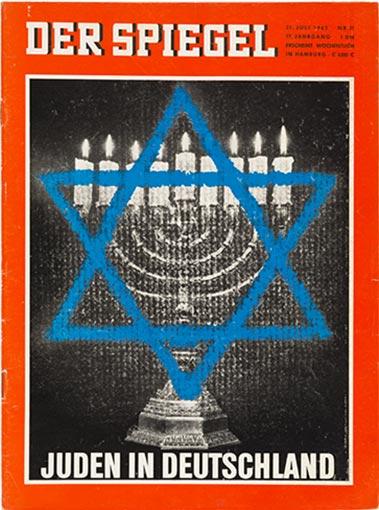

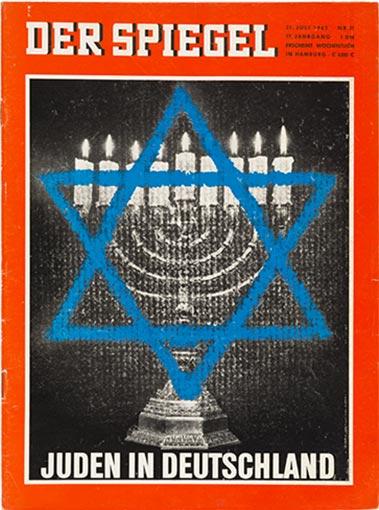

In 1965, 52 of his photographs were published with accompanying texts under the title Deutsche Juden heute (German Jews Today). These images and texts focus on the Jewish communities and discuss the relationship between Jews and Germans. Jewish life is fragile; there are only a few small communities whose existence is controversial both within and outside of Germany. The themes in Freed’s book were also discussed in two earlier publications that appeared in 1963 and 1964: an issue of the news magazine Der Spiegel with the title “Juden in Deutschland” (Jews in Germany); and a volume published by Hermann Kesten called ich lebe nicht in der Bundesrepublik (I don’t live in the Federal Republic). The question of whether it is possible to live as a Jew in Germany shapes a debate that lasts until today.

All 52 photographs from Leonard Freed’s series, purchased from the photographer’s widow Brigitte Freed, are part of the museum’s collection. They are exhibited in their entirety for the first time.

Leonard Freed’s Photo Series German Jews Today

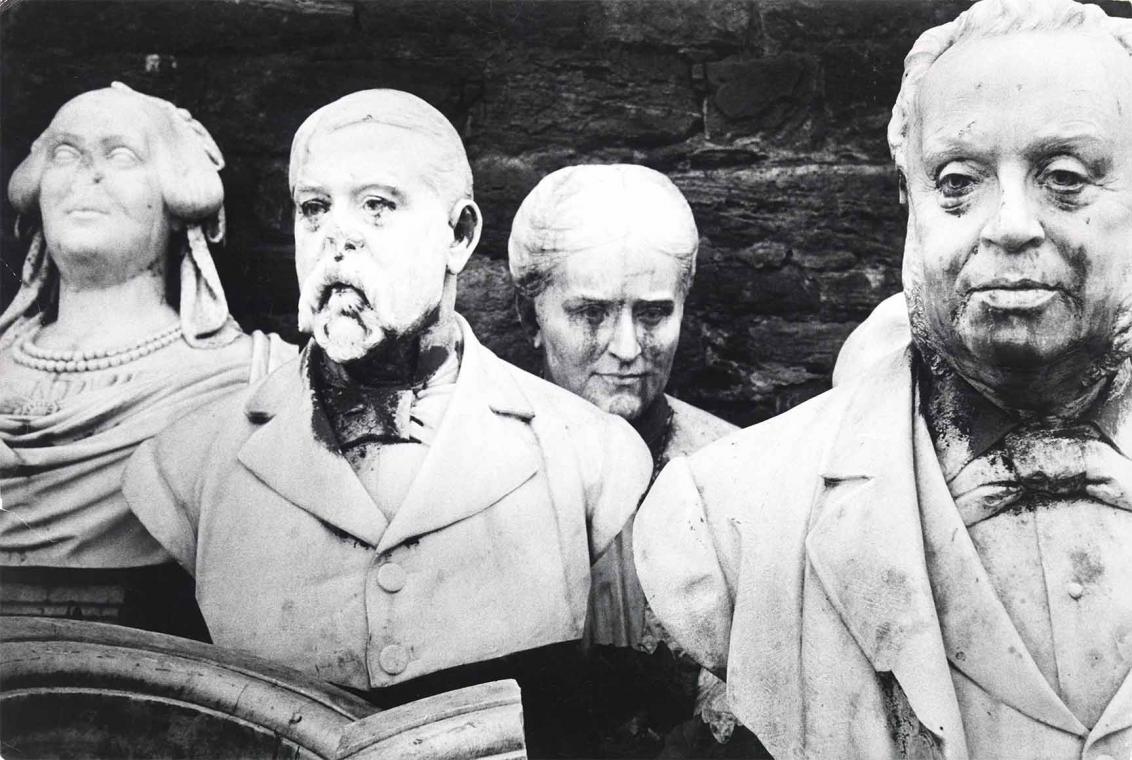

Leonard Freed, Marble busts in front of the wall of the old Jewish cemetery, Frankfurt am Main, 1961; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2008/305/1.

Further information about this photo can be found in our online collections (in German)

Leonard Freed, Jewish cemetery, Worms, 1961; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2008/305/2.

Further information about this photo can be found in our online collections (in German)

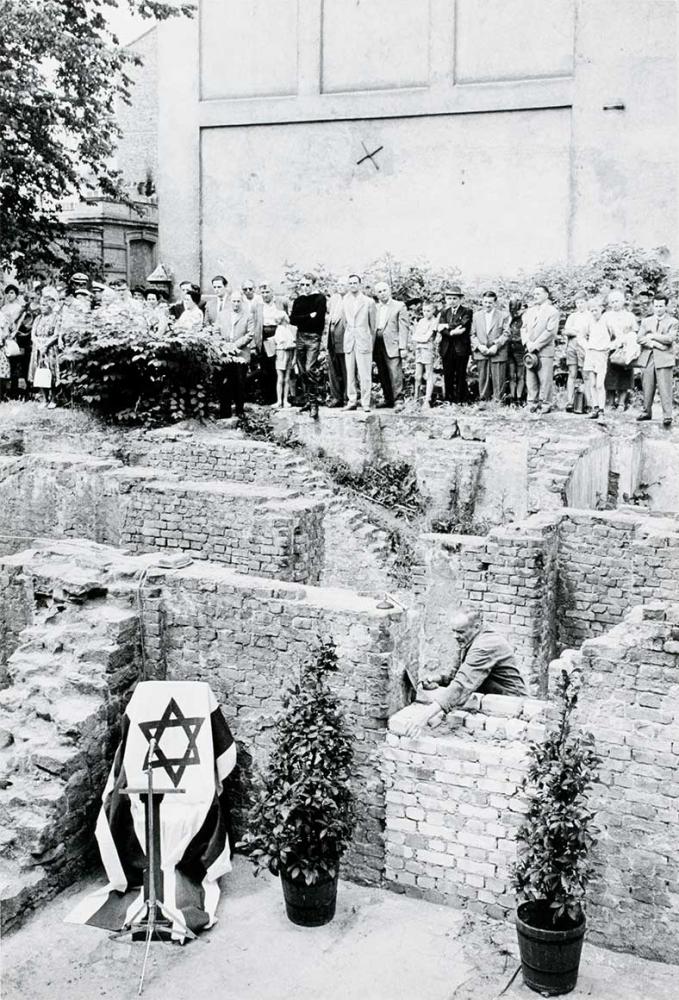

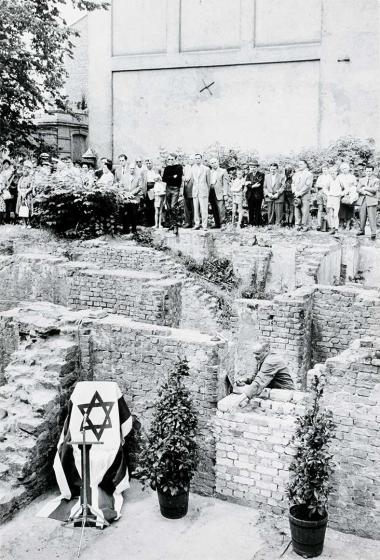

Leonard Freed, Groundbreaking ceremony for the new synagogue, Mainz, 18. Juni 1962; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2006/198/13.

Further information about this photo can be found in our online collections (in German)

Leonard Freed, Re-dedication of the synagogue, Worms, 1961; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2008/305/31.

Further information about this photo can be found in our online collections (in German)

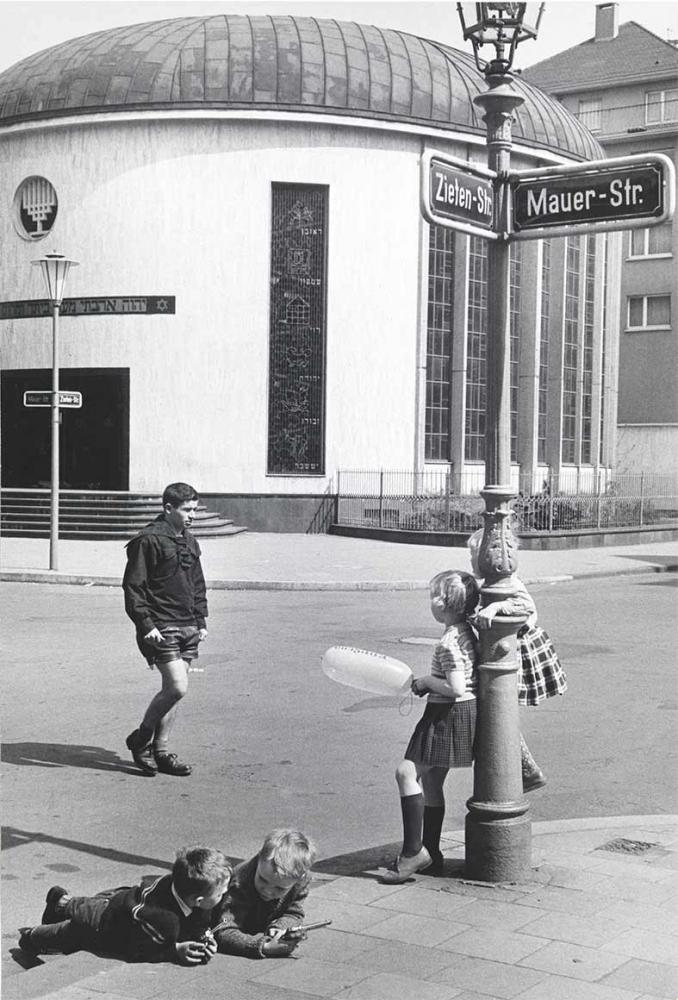

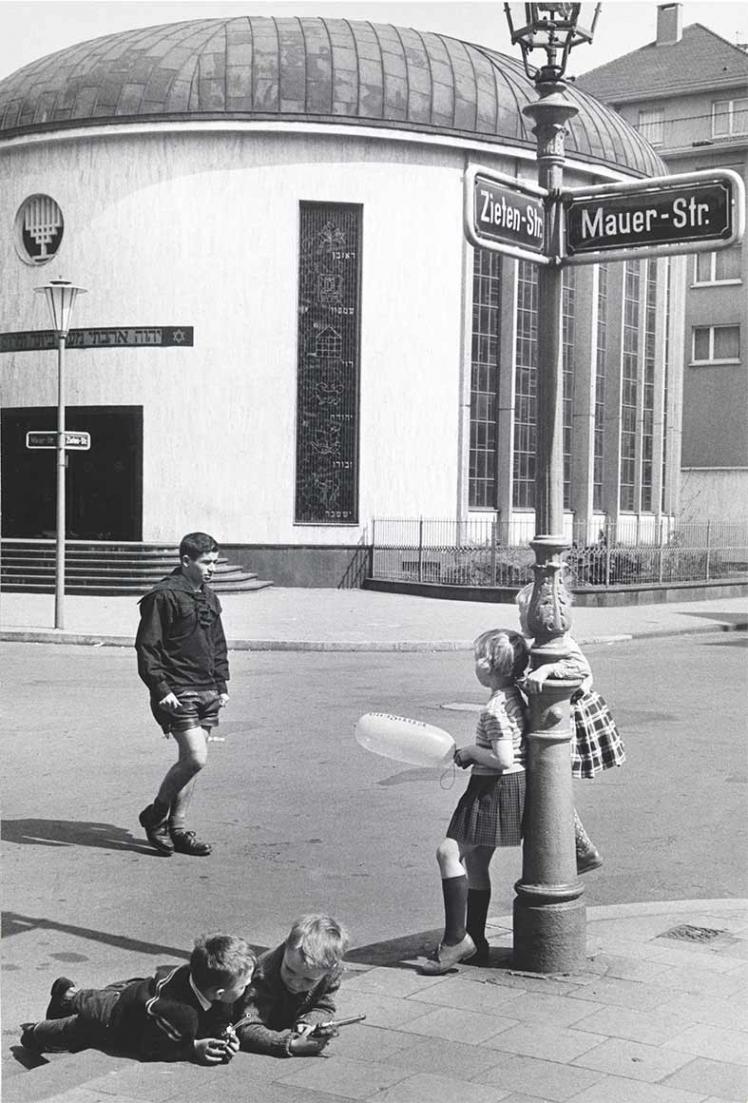

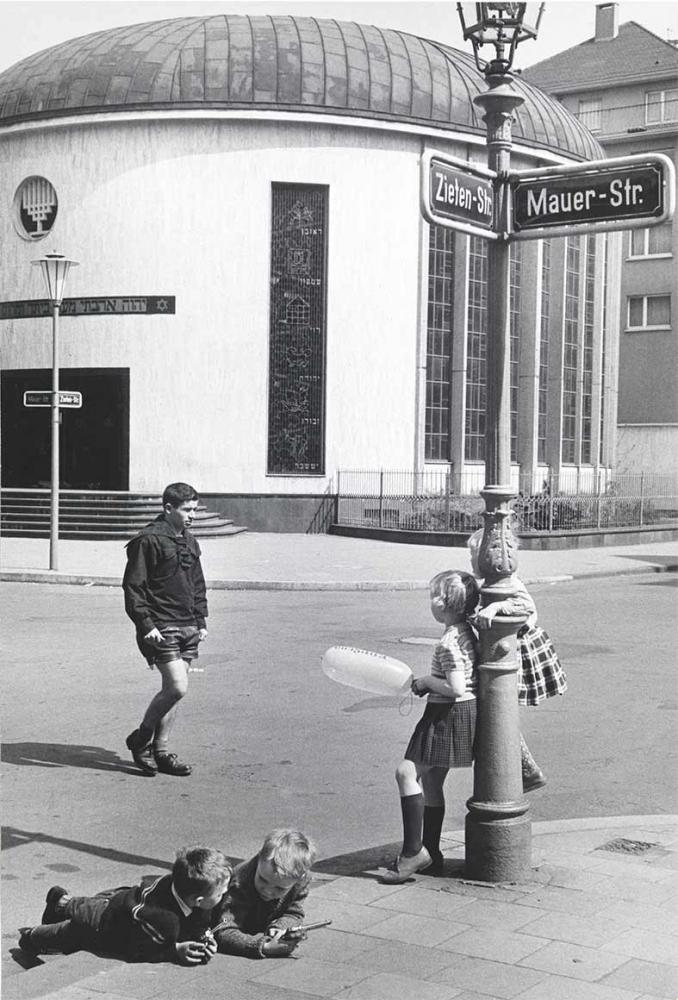

Leonard Freed, New synagogue and new community center, Düsseldorf, 1961; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2008/305/3.

Further information about this photo can be found in our online collections (in German) as well as in the essay The New Synagogue in Düsseldorf: A Symbol of the Eternal “Nevertheless” further down on this page

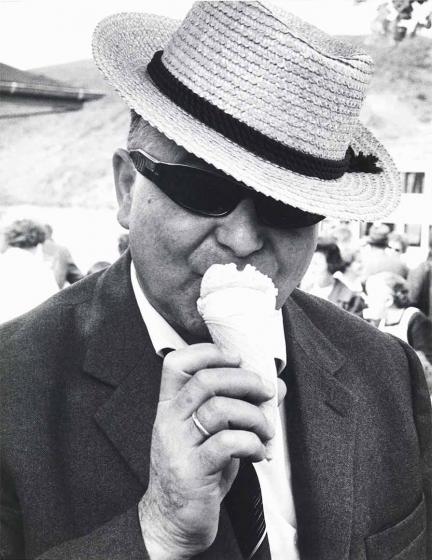

Leonard Freed, Hugo Spiegel (1905‒1987) as the champion shot, Warendorf, 1962; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2006/198/3.

Further information about this photo can be found in our online collections (in German)

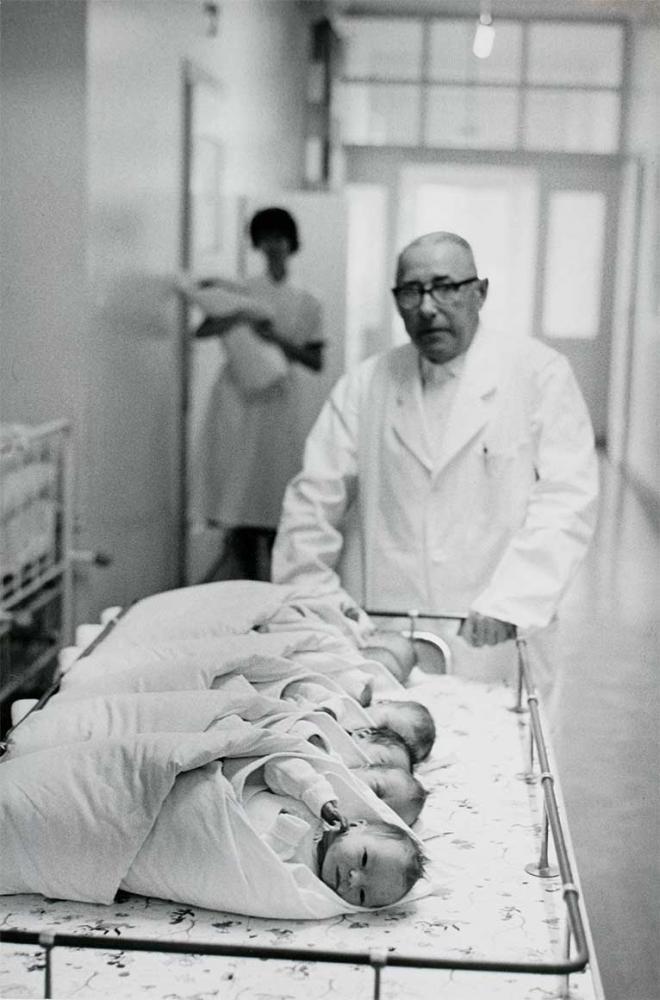

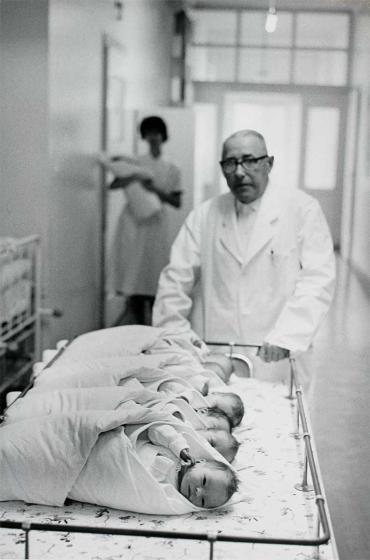

Leonard Freed, In the Jewish hospital, West-Berlin, 1961; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2008/305/4.

Further information about this photo can be found in our online collections (in German)

Leonard Freed, Arm of a woman with a tattooed number from the Auschwitz concentration camp, on a ship on the river Rhine, 1961; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2008/305/5.

Further information about this photo can be found in our online collections (in German)

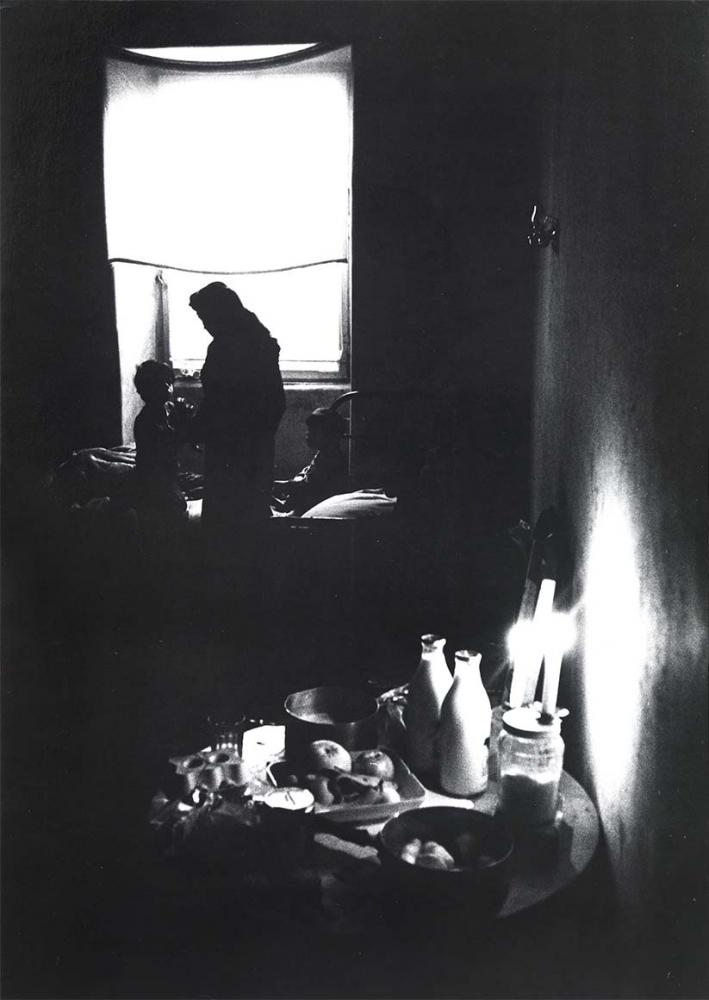

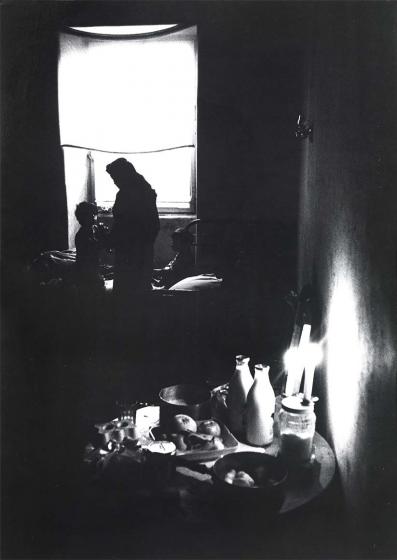

Leonard Freed, Apartment of a poor family, Frankfurt am Main, 1961; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2008/305/6.

Further information about this photo can be found in our online collections (in German)

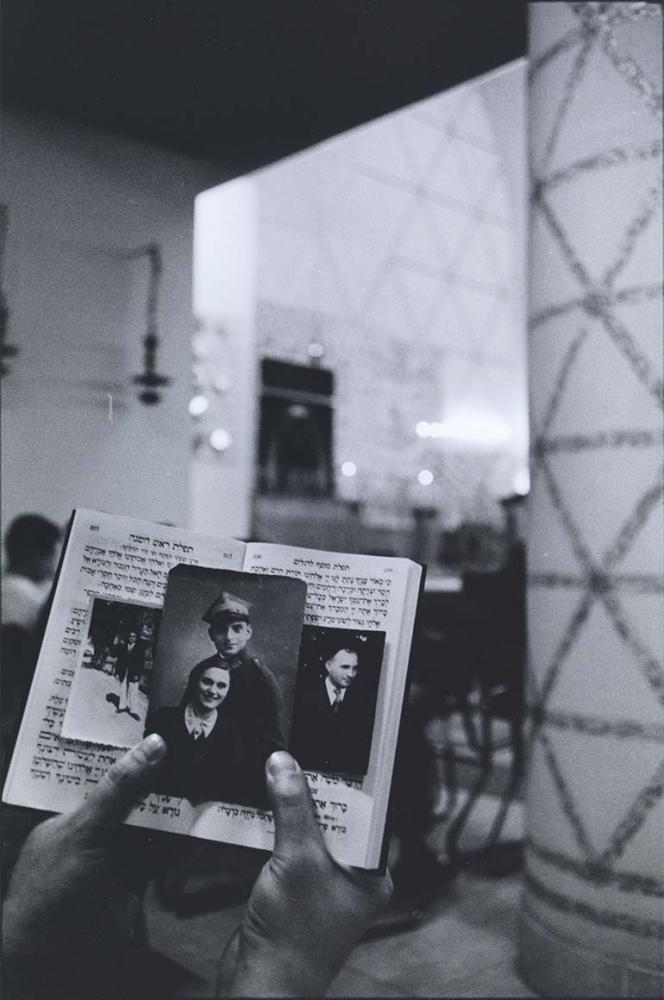

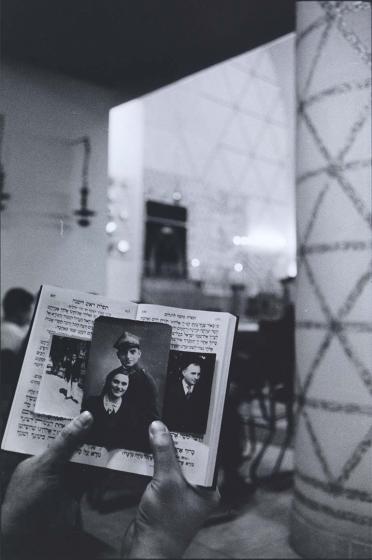

Leonard Freed, Photographs of relatives in the prayer book of a member of the Jewish community, Frankfurt am Main, 1961; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2008/305/32.

Further information about this photo can be found in our online collections (in German)

Leonard Freed, Wooden grating over the blood trenches in the former concentration camp, Dachau, 1965; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2008/305/7.

Further information about this photo can be found in our online collections (in German)

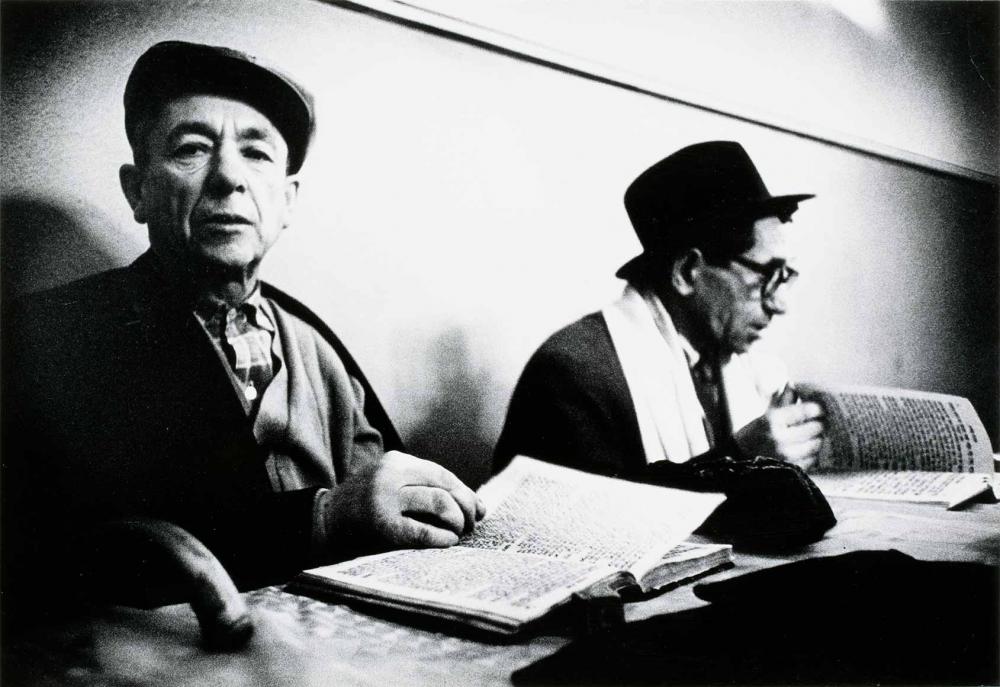

Leonard Freed, In the Polish prayer room, Frankfurt am Main, 1961; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2006/198/9.

Further information about this photo can be found in our online collections (in German)

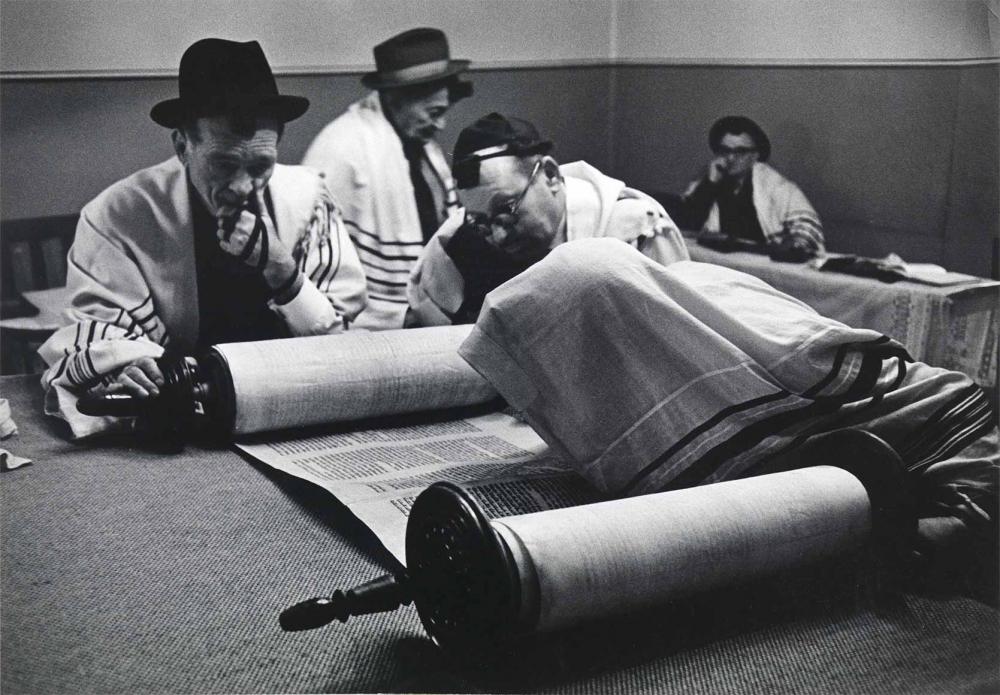

Leonard Freed, Morning service in the Polish prayer room, Frankfurt am Main, 1961; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2008/305/8.

Further information about this photo can be found in our online collections (in German)

Leonard Freed, Reading the Torah in the Polish prayer room, Frankfurt am Main, 1961; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2008/305/9.

Further information about this photo can be found in our online collections (in German)

Leonard Freed, After the reading of the Torah in the Polish prayer room, Frankfurt am Main, 1961; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2008/305/10.

Further information about this photo can be found in our online collections (in German)

Leonard Freed, Havdalah ceremony in the Polish prayer room, Frankfurt am Main, 1961; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2008/305/11.

Further information about this photo can be found in our online collections (in German)

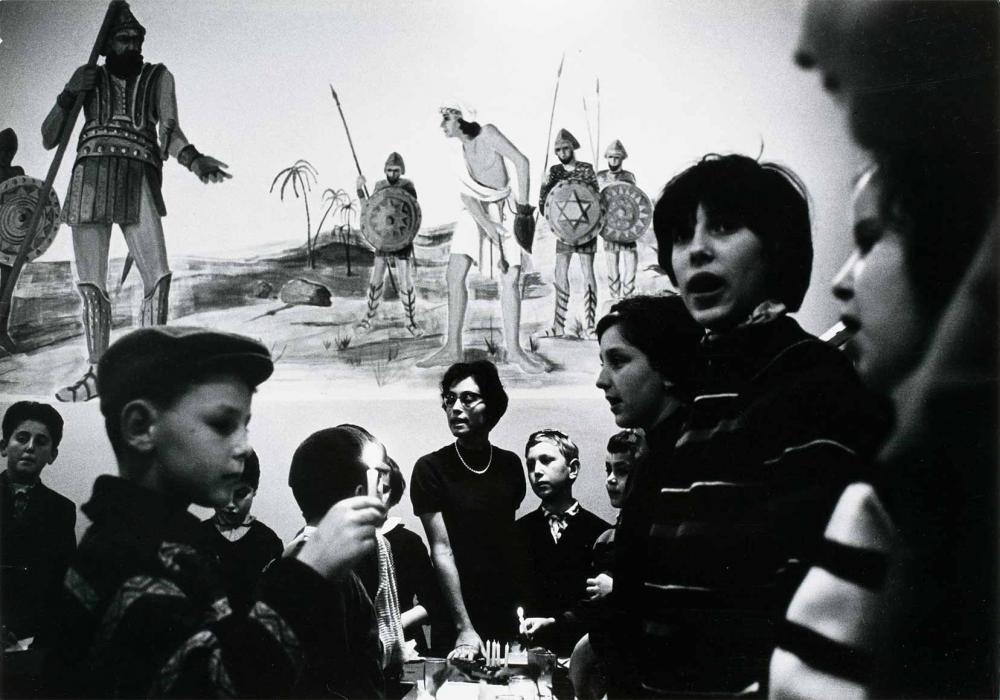

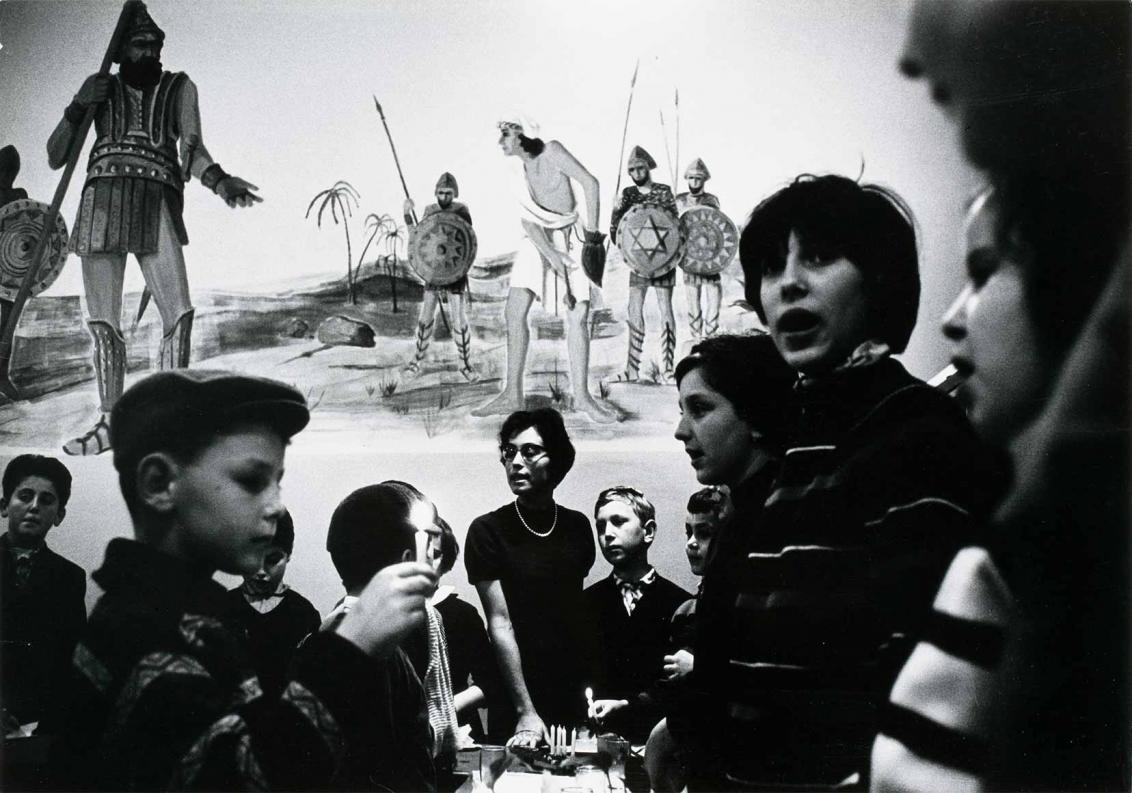

Leonard Freed, Hanukkah in the Jewish community, Frankfurt am Main, 1961; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2006/198/5.

Further information about this photo can be found in our online collections (in German) as well as in the essay “Another Book About the Jews?” further down on this page

Leonard Freed, Girl, Düsseldorf, 1961; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2008/305/12.

Further information about this photo can be found in our online collections (in German)

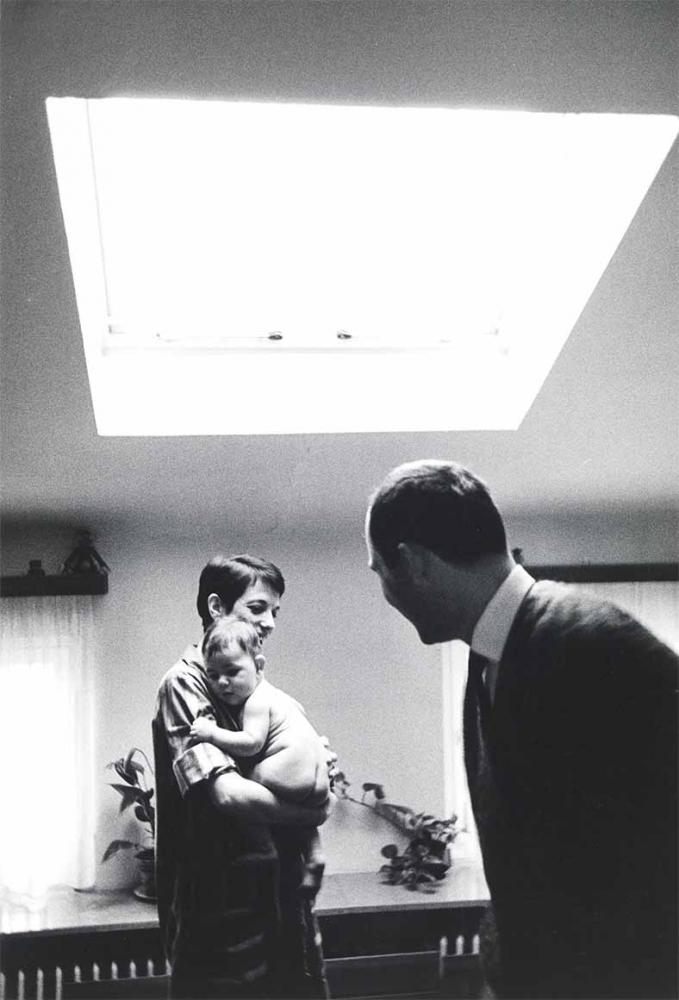

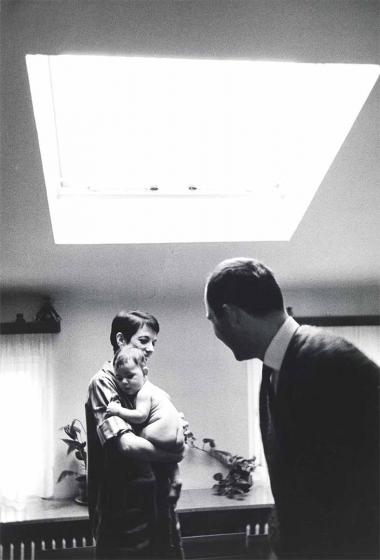

Leonard Freed, Young married couple, Düsseldorf, 1962; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2008/305/13.

Further information about this photo can be found in our online collections (in German)

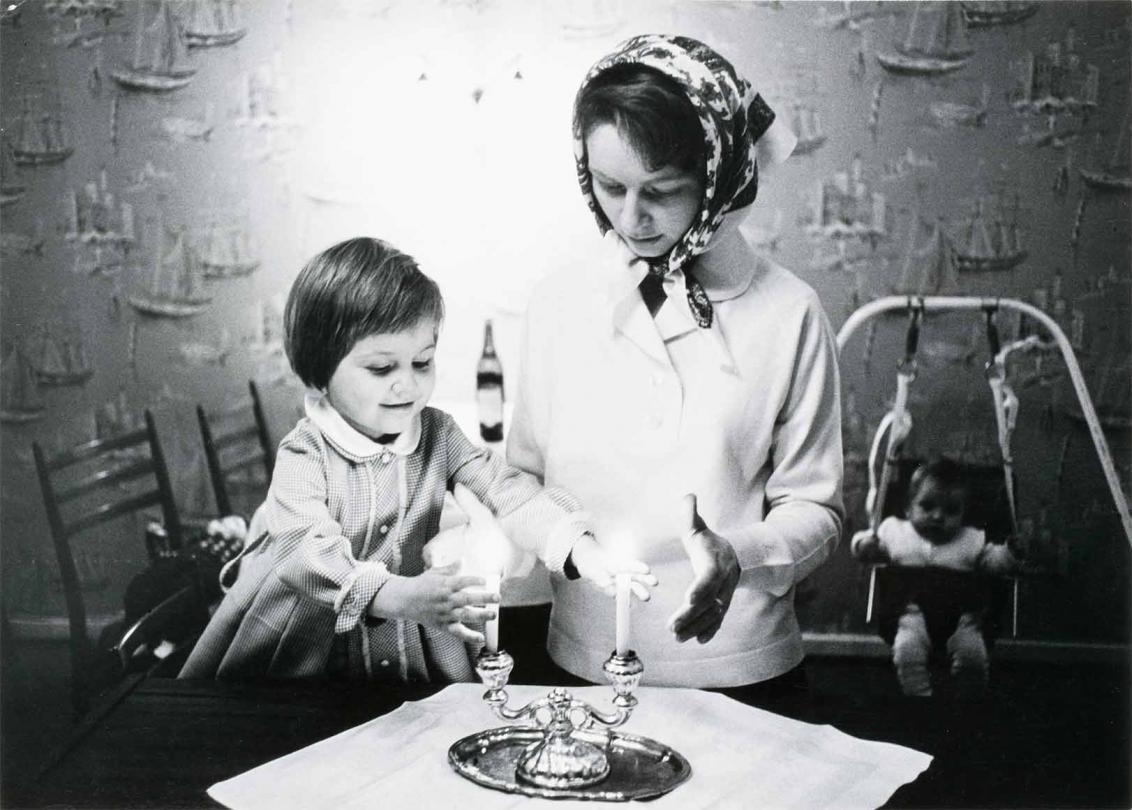

Leonard Freed, Lighting the candles on Shabbat, Frankfurt am Main, 1961; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2006/198/7.

Further information about this photo can be found in our online collections (in German)

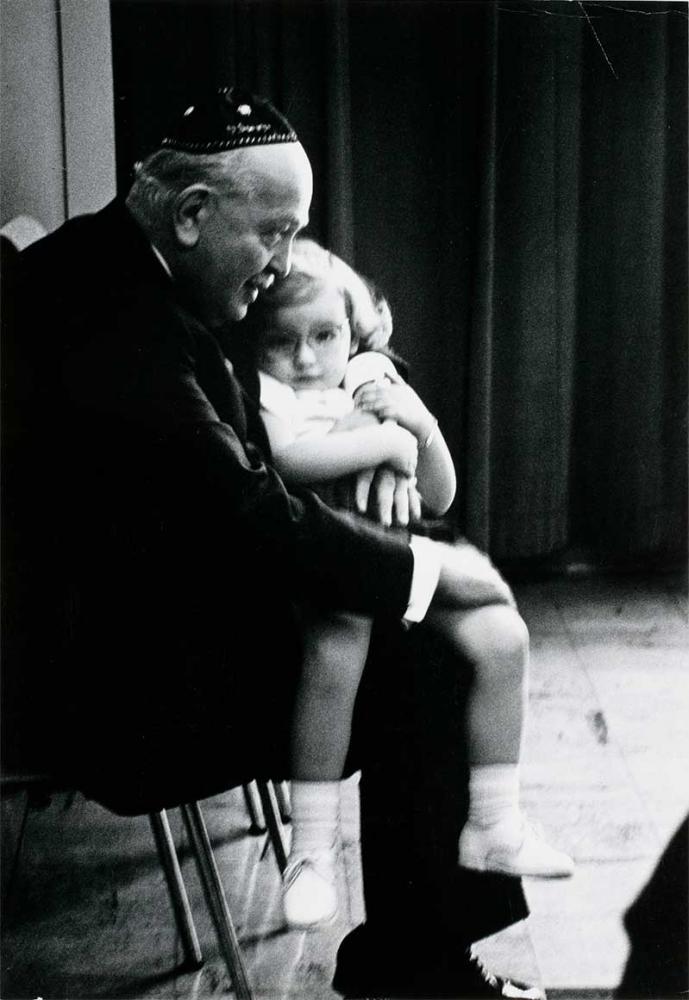

Leonard Freed, Grandfather and grandchild, Düsseldorf, 1961; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2006/198/10.

Further information about this photo can be found in our online collections (in German)

Leonard Freed, Wedding ceremony in the synagogue, West-Berlin, 1961; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2008/305/33.

Further information about this photo can be found in our online collections (in German) as well as in the essay “Another Book About the Jews?” further down on this page

Leonard Freed, Bar Mitzvah celebration, Düsseldorf, 1961; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2008/305/14.

Further information about this photo can be found in our online collections (in German)

Leonard Freed, Bar Mitzvah, Düsseldorf, 1961; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2006/198/1.

Further information about this photo can be found in our online collections (in German)

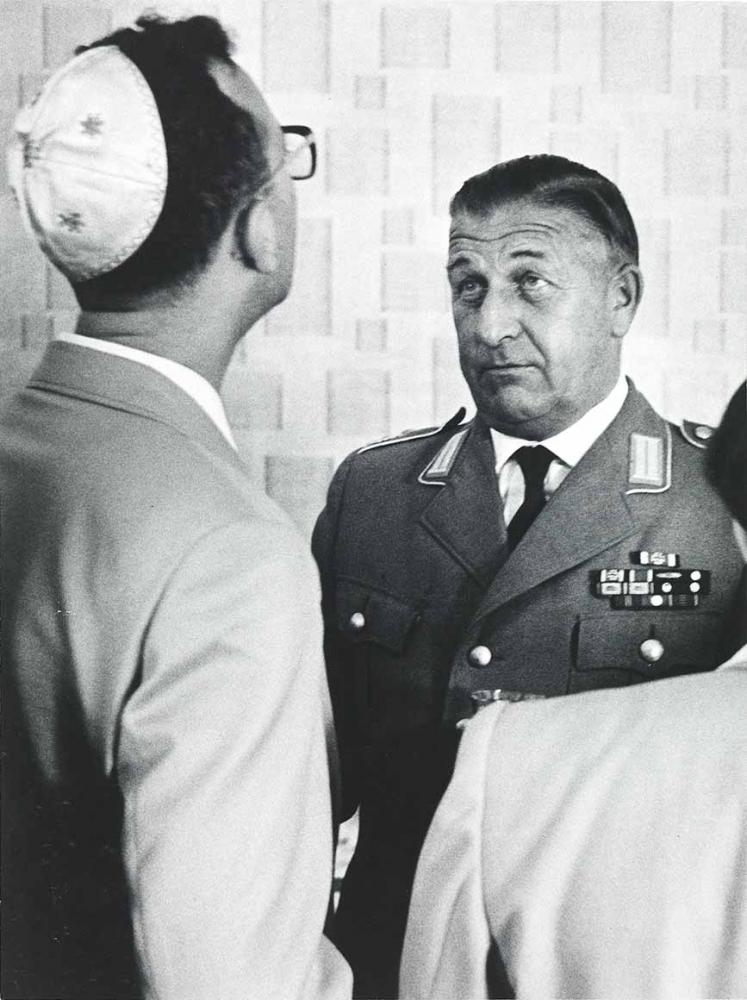

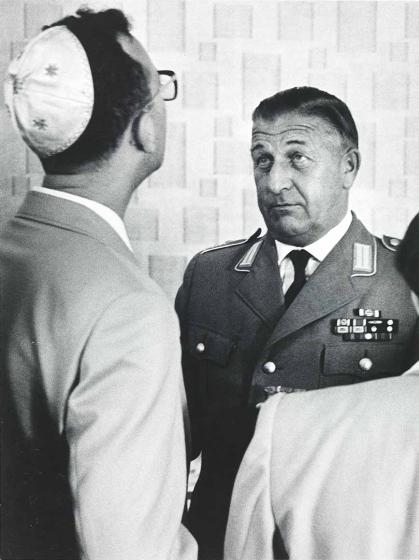

Leonard Freed, The chief of the city’s police in the Jewish community hall, Mainz, 1961; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2008/305/15.

Further information about this photo can be found in our online collections (in German)

Leonard Freed, The synagogue’s chief cantor, Köln, 1961; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2008/305/16.

Further information about this photo can be found in our online collections (in German)

Leonard Freed, Before service in the synagogue, Düsseldorf, 1961; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2008/305/17.

Further information about this photo can be found in our online collections (in German) as well as in the essay The New Synagogue in Düsseldorf: A Symbol of the Eternal “Nevertheless” further down on this page

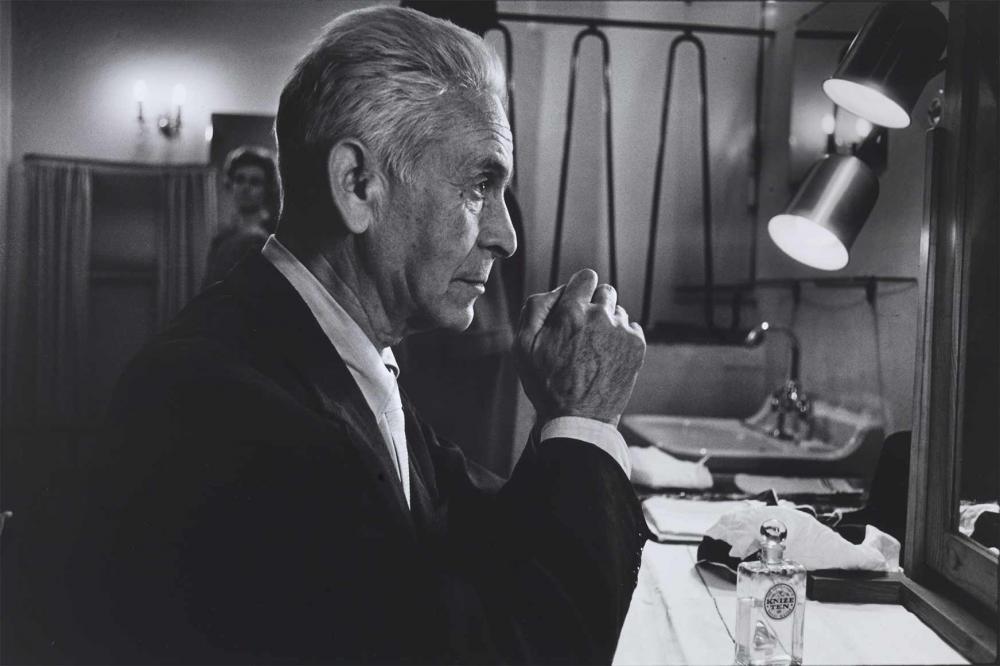

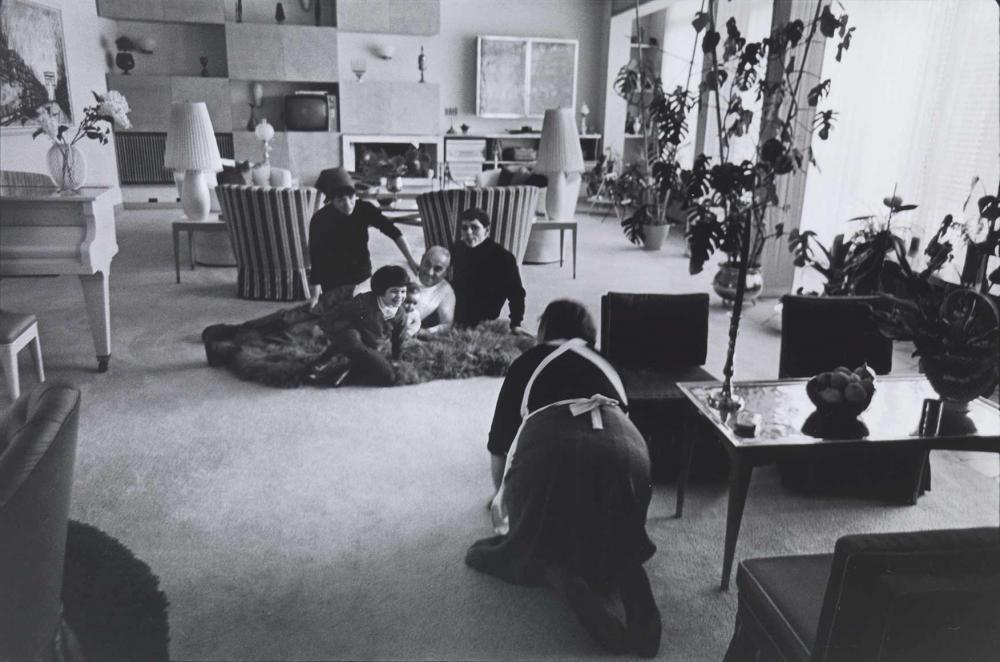

Leonard Freed, Simhat Torah ball, Köln, 1961; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2006/198/8.

Further information about this photo can be found in our online collections (in German)

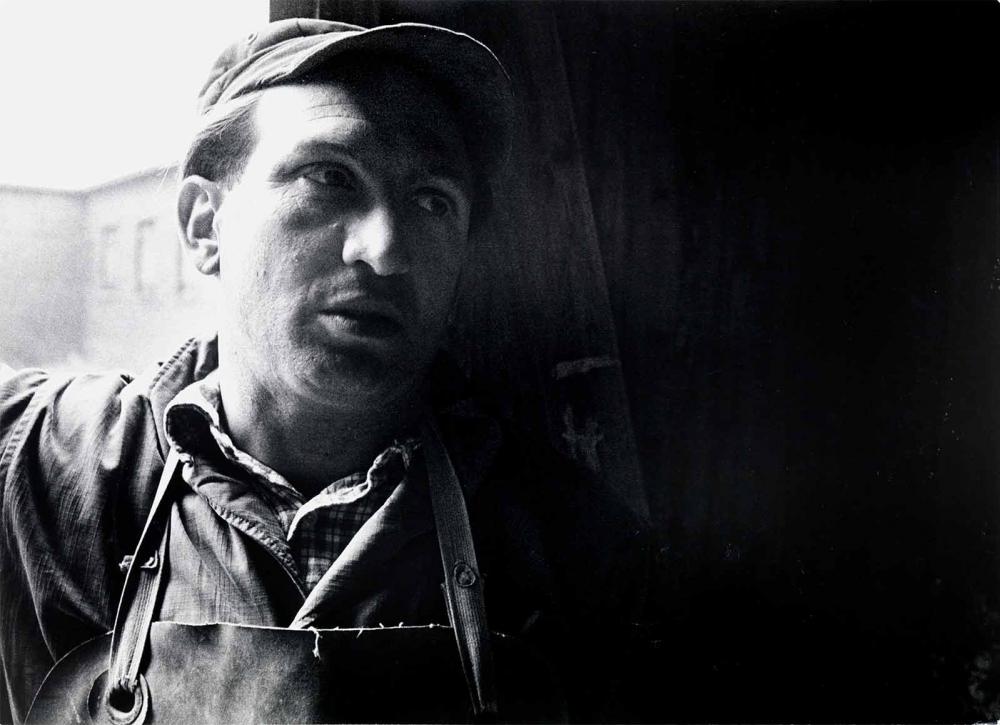

Leonard Freed, Stonemason Jakob Horowitz, Frankfurt am Main, 1961; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2008/305/18.

Further information about this photo can be found in our online collections (in German)

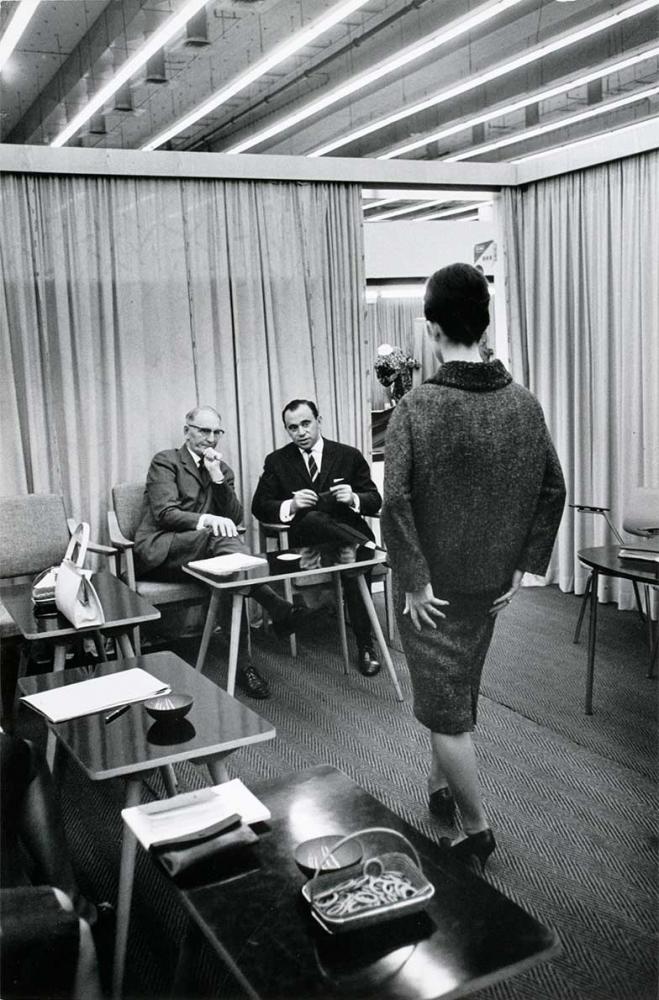

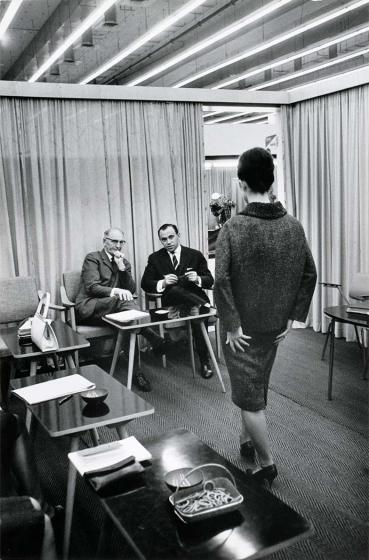

Leonard Freed, Textile manufacturer Arno Lustiger (1924‒2012), Düsseldorf, 1961; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2006/198/12.

Further information about this photo can be found in our online collections (in German)

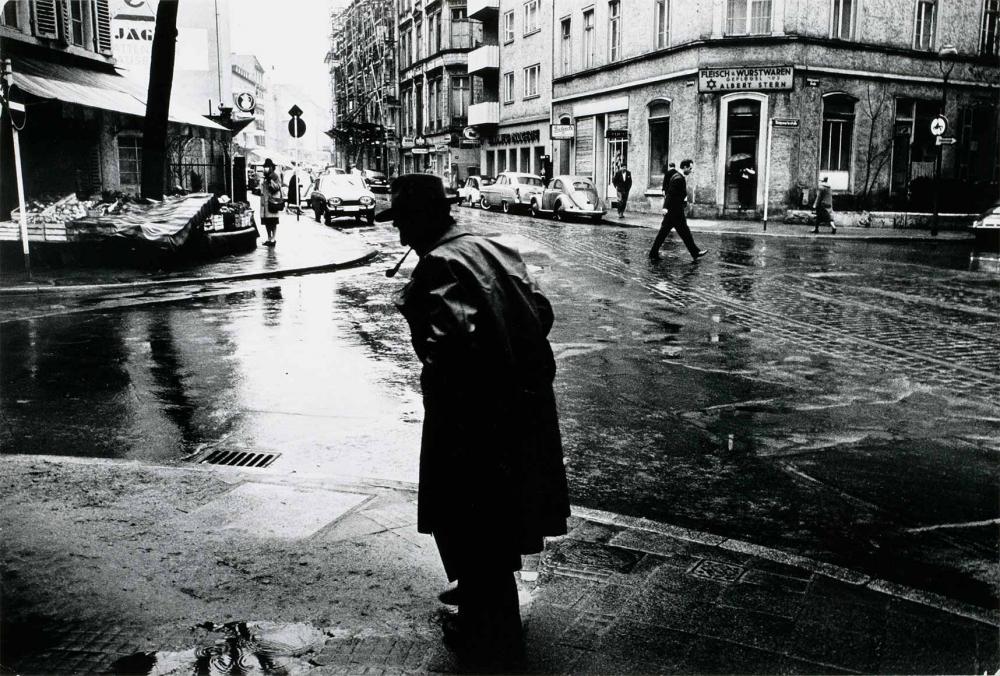

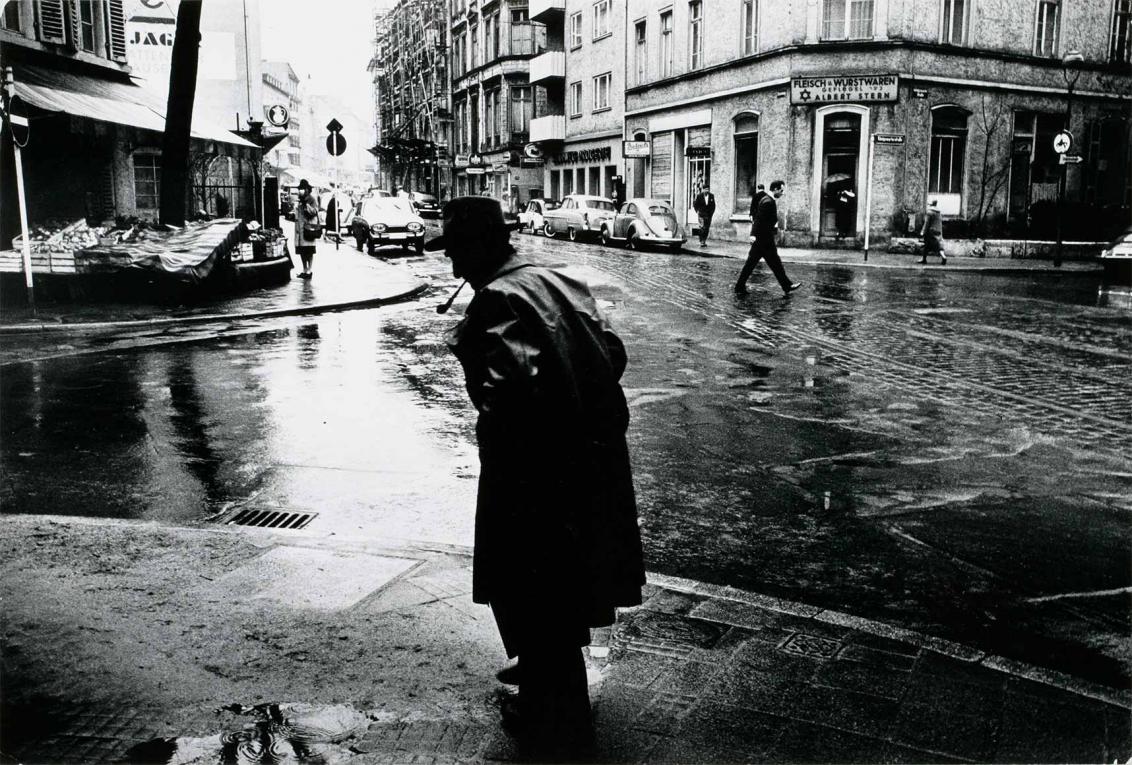

Leonard Freed, Kosher butcher on a street corner, Frankfurt am Main, 1961; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2006/198/11.

Further information about this photo can be found in our online collections (in German)

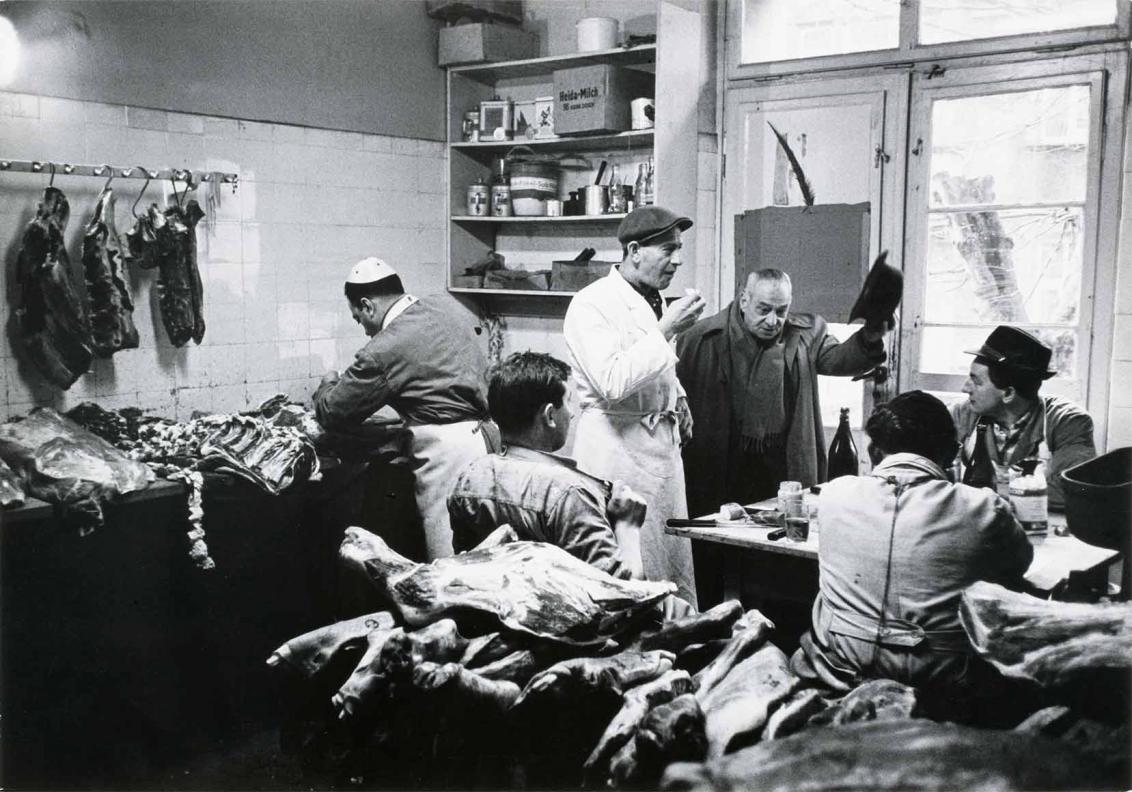

Leonard Freed, Kosher slaughterhouse, Frankfurt am Main, 1961; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2006/198/6.

Further information about this photo can be found in our online collections (in German)

Leonard Freed, Insurance inspector Walter Seligmann, on a ship on the river Rhine, 1961; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2008/305/19.

Further information about this photo can be found in our online collections (in German)

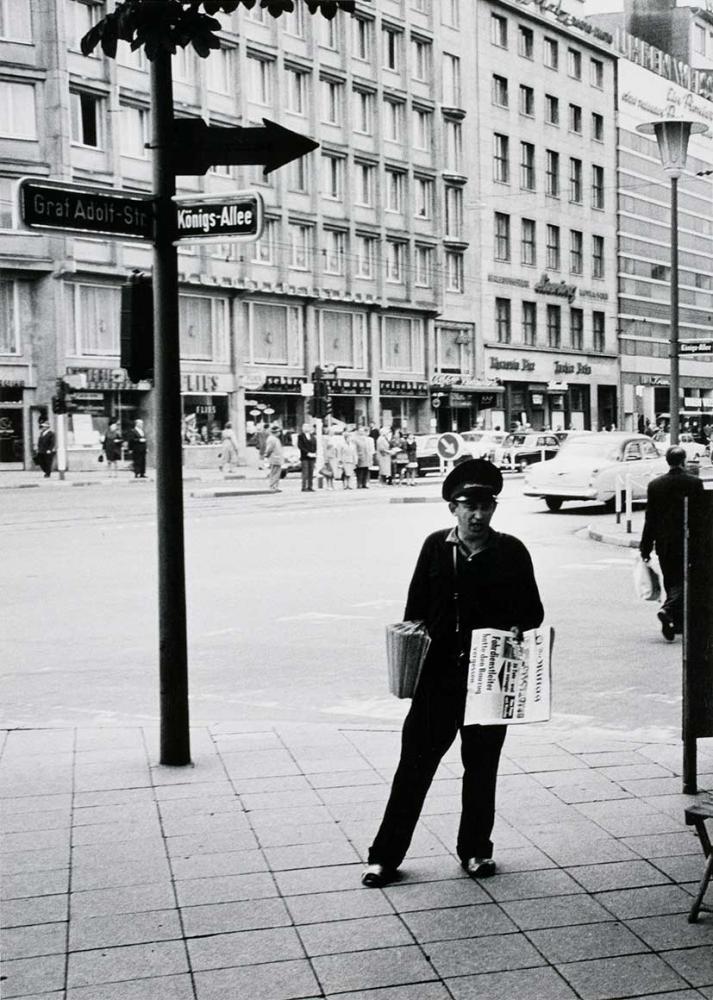

Leonard Freed, Newspaper salesman Streigold, Düsseldorf, 1961; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2006/198/2.

Further information about this photo can be found in our online collections (in German)

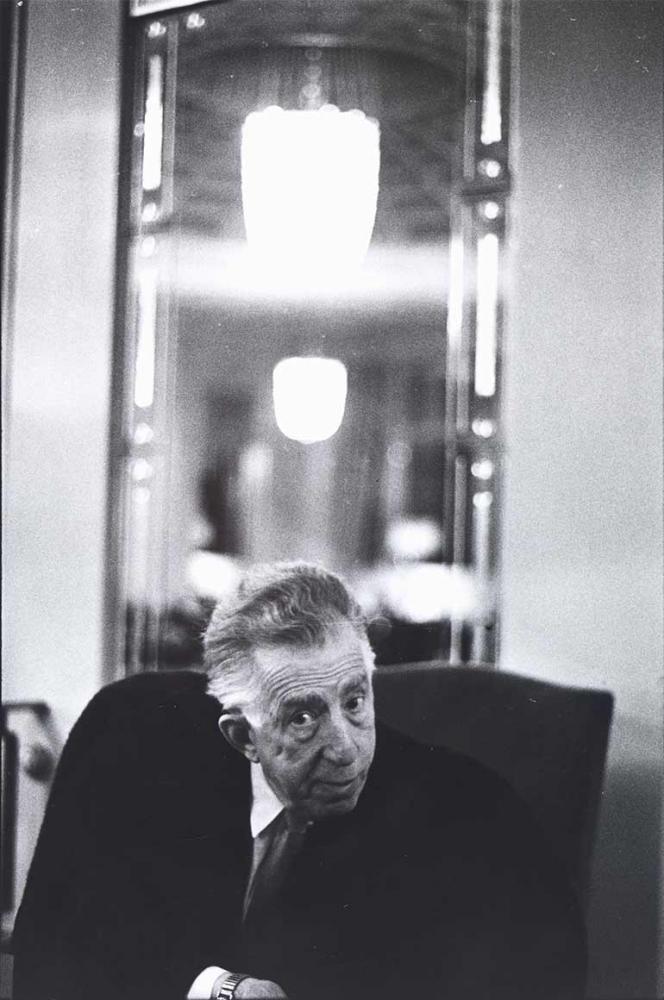

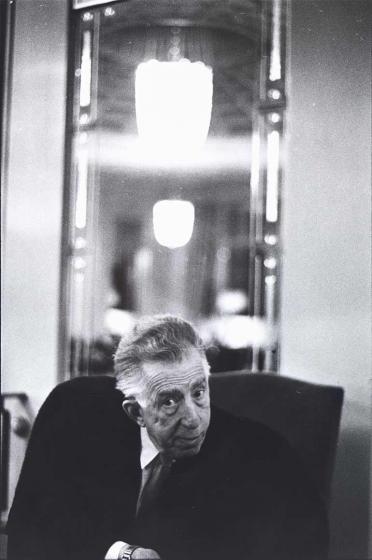

Leonard Freed, Ernst Deutsch (1890–1969), West-Berlin, 1961; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2008/305/34.

Further information about this photo can be found in our online collections (in German)

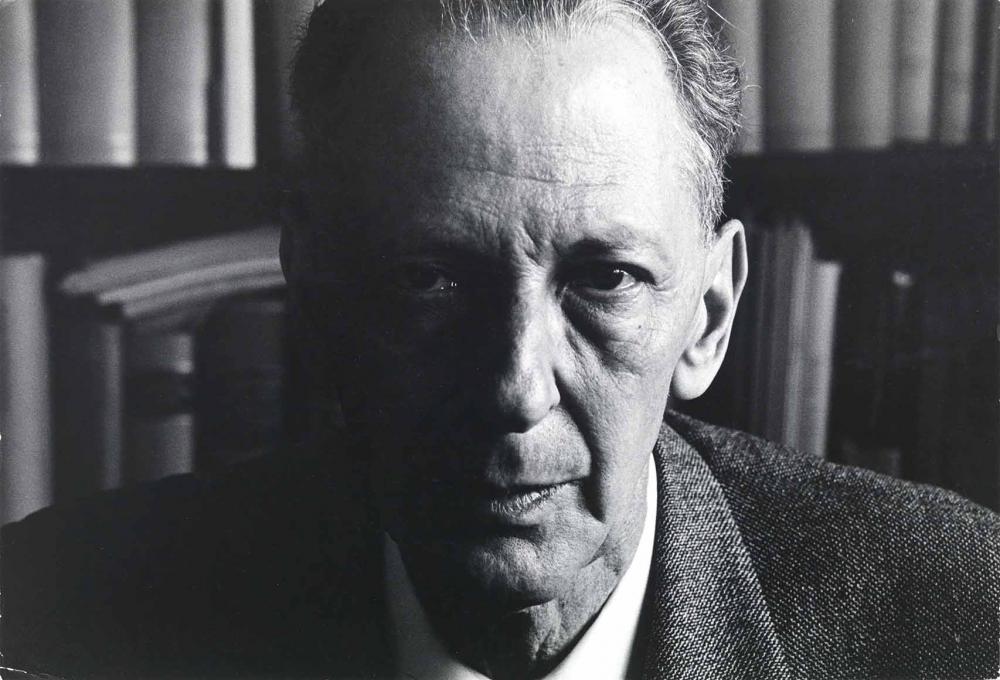

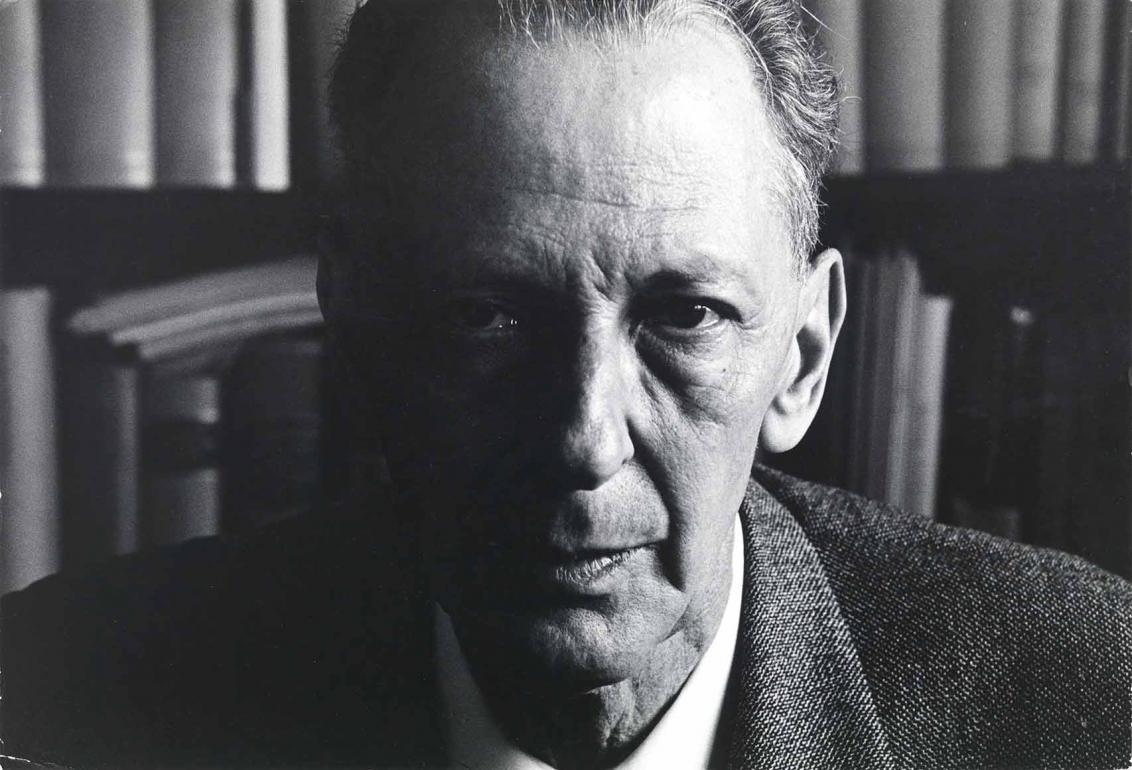

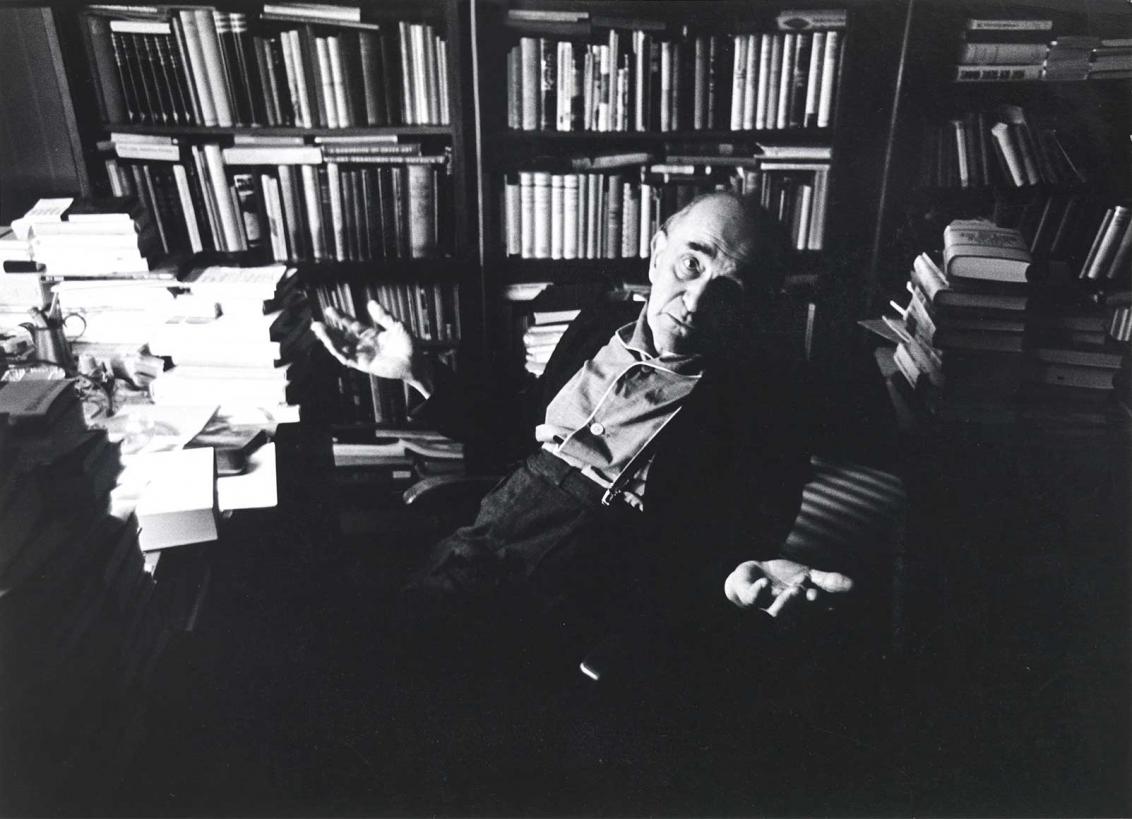

Leonard Freed, Alfred Kantorowicz (1899–1979), Hamburg, 1961; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2008/305/20.

Further information about this photo can be found in our online collections (in German)

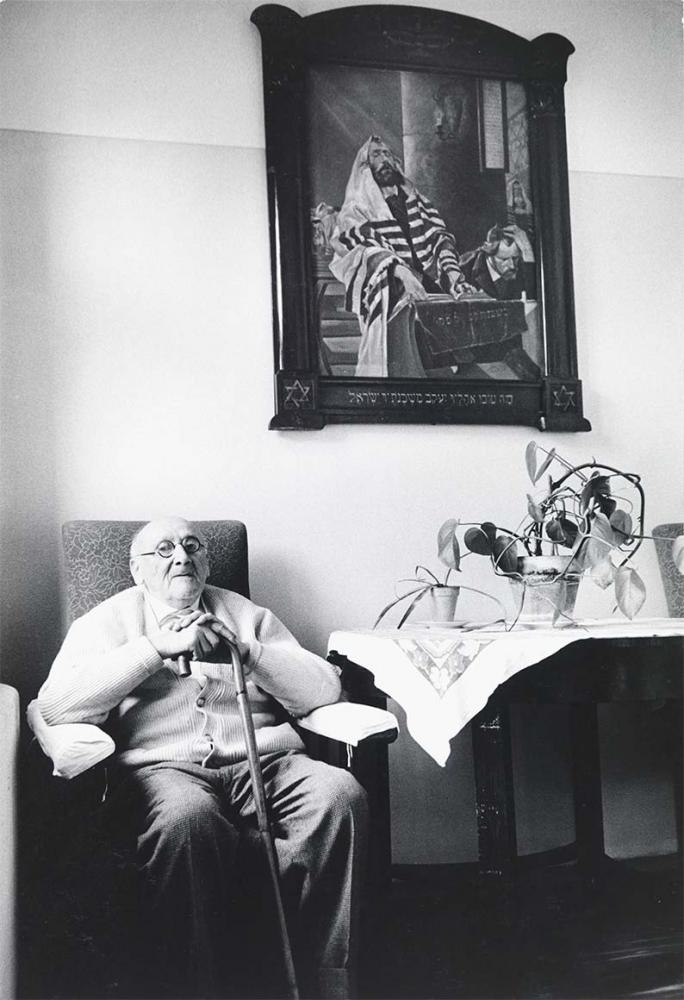

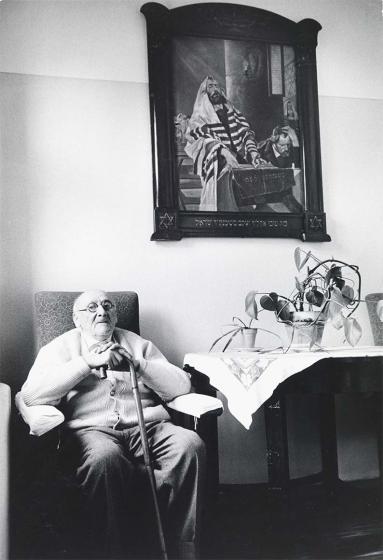

Leonard Freed, Herbert Lewin (1899–1982), Offenbach am Main, 1964; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2006/198/4.

Further information about this photo can be found in our online collections (in German)

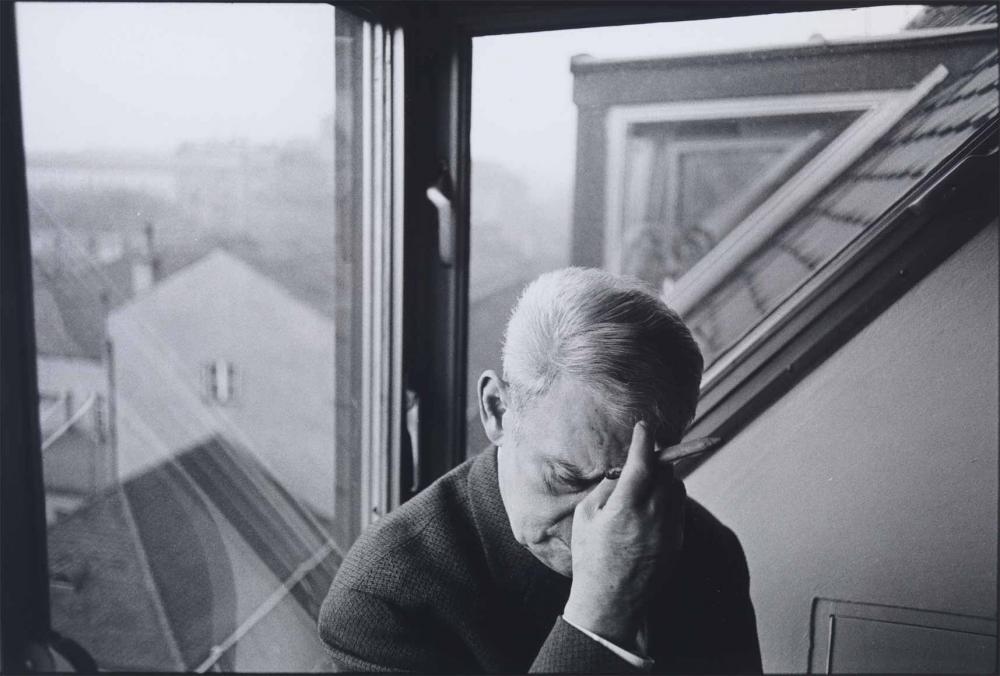

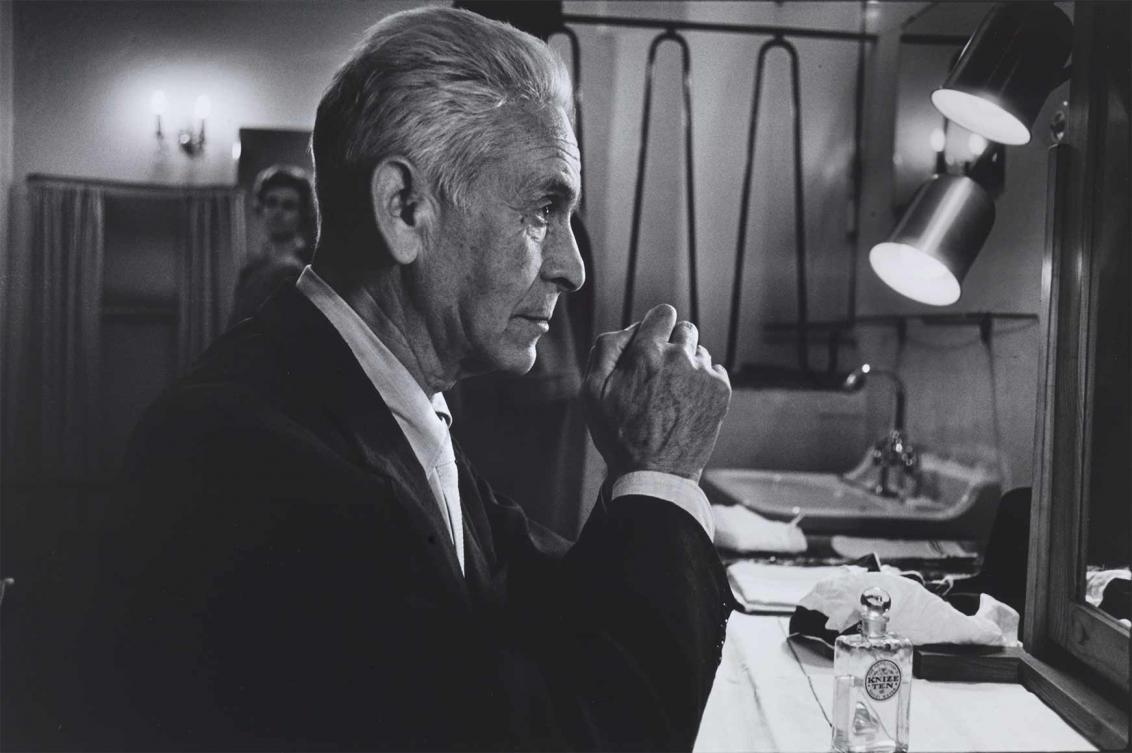

Leonard Freed, Fritz Kortner (1892–1970), München, 1962; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2008/305/35.

Further information about this photo can be found in our online collections (in German)

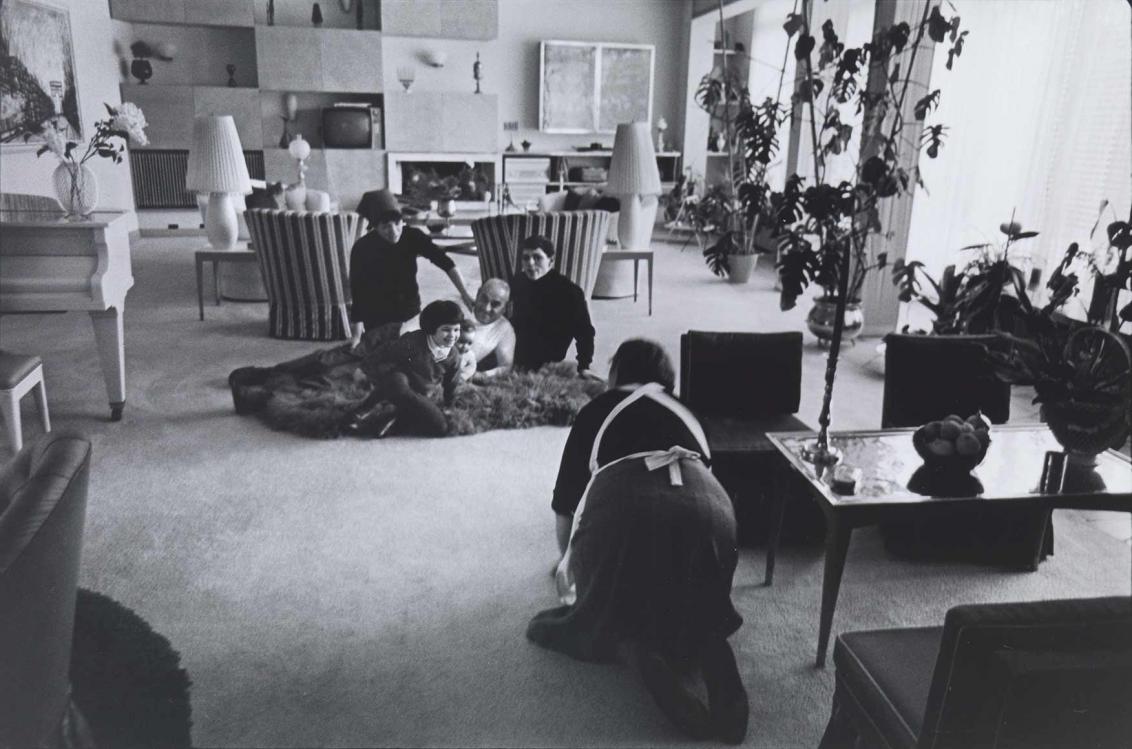

Leonard Freed, Artur Brauner (1918–2019) with his family, West-Berlin, 1962; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2008/305/36.

Further information about this photo can be found in our online collections (in German)

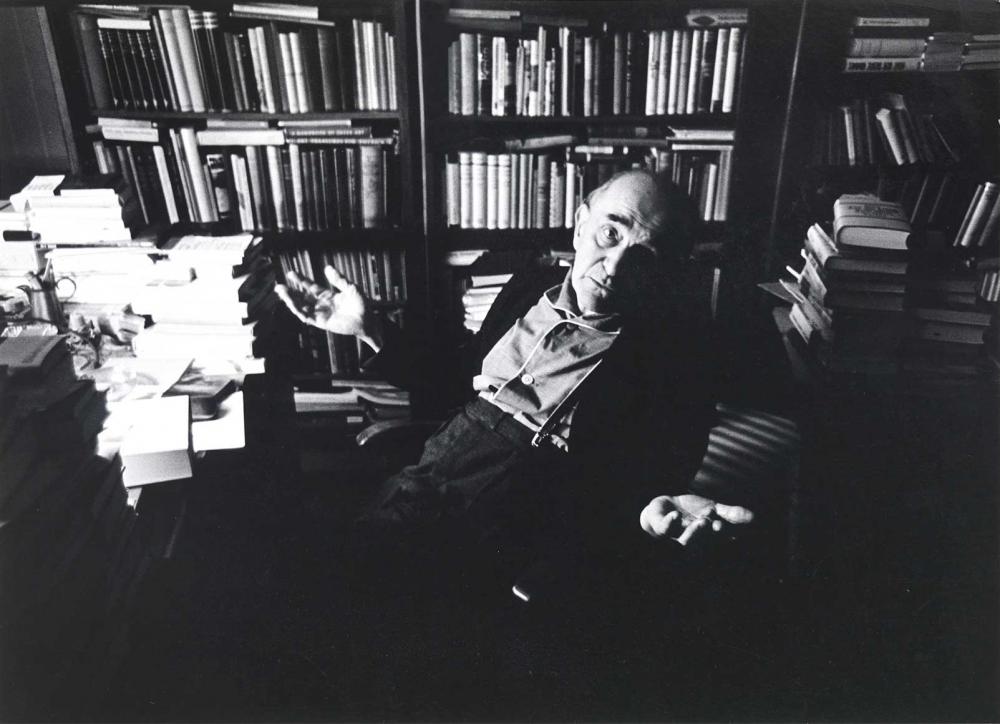

Leonard Freed, Ludwig Marcuse (1894–1971), Frankfurt am Main, 1962; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2008/305/37.

Further information about this photo can be found in our online collections (in German)

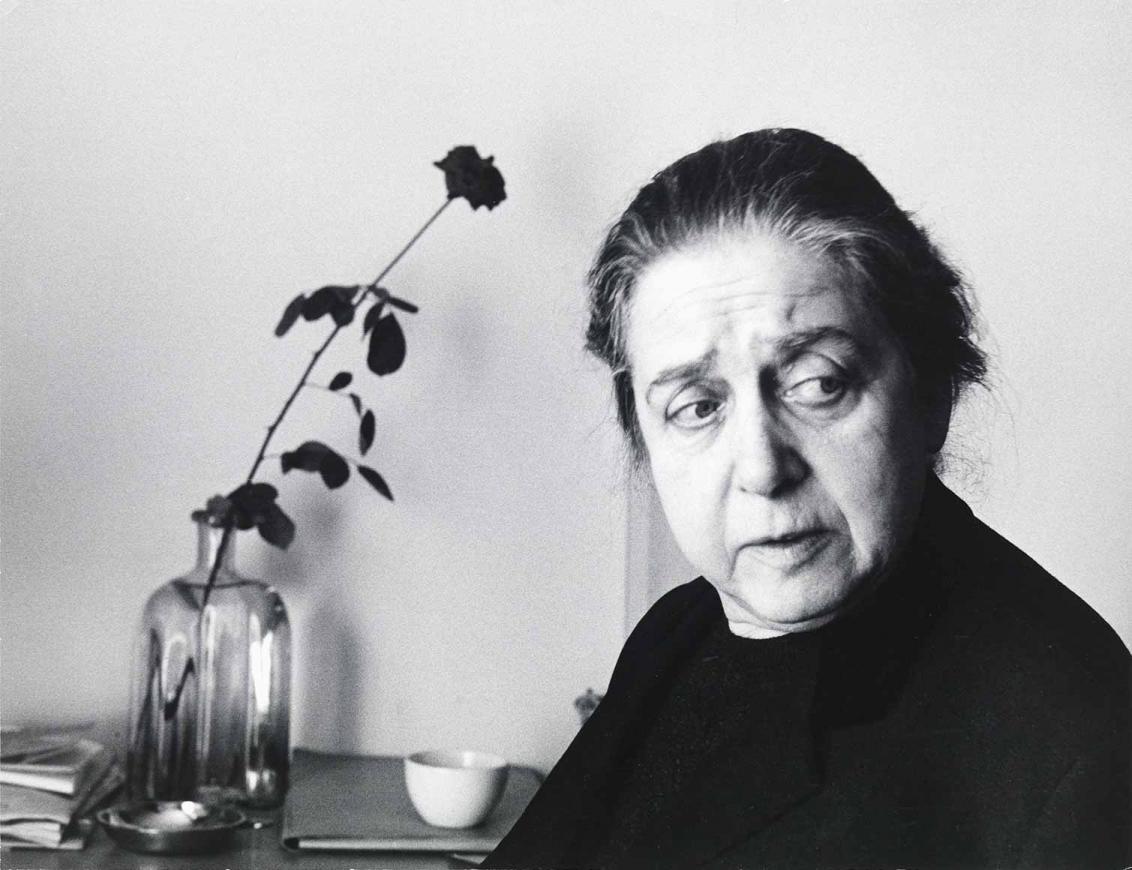

Leonard Freed, Therese Giehse (1898–1975), München, 1961; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2008/305/21.

Further information about this photo can be found in our online collections (in German)

Leonard Freed, Willy Haas (1891–1973), Hamburg, 1961; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2008/305/22.

Further information about this photo can be found in our online collections (in German)

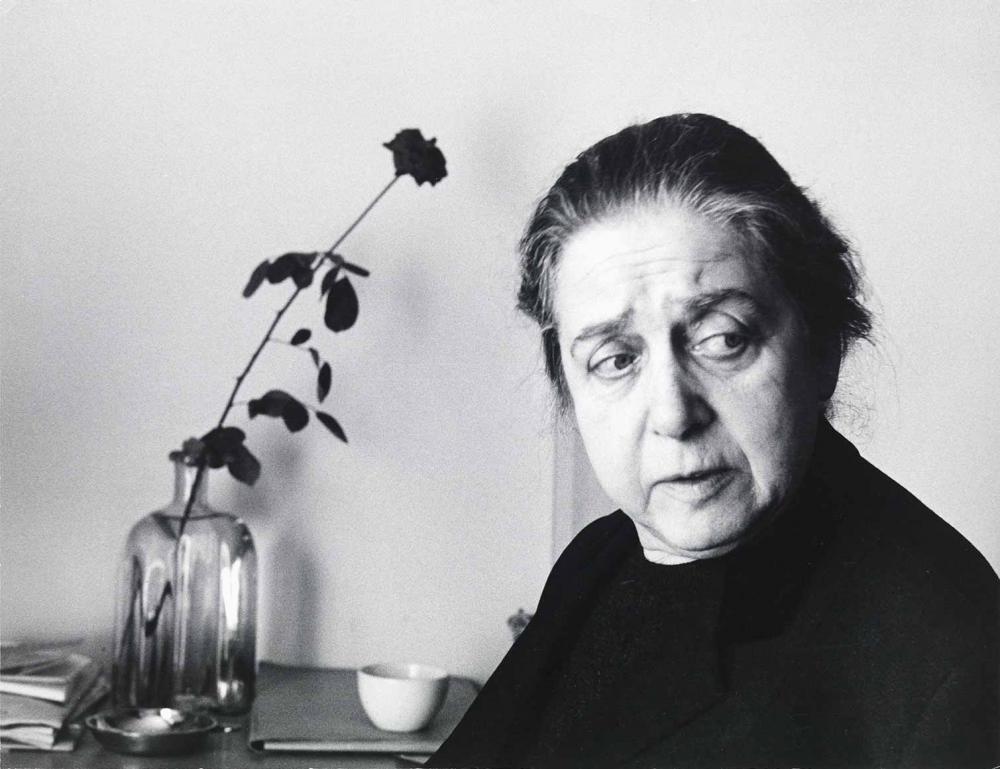

Leonard Freed, Ida Ehre (1900–1989), Hamburg, 1961; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2008/305/38.

Further information about this photo can be found in our online collections (in German)

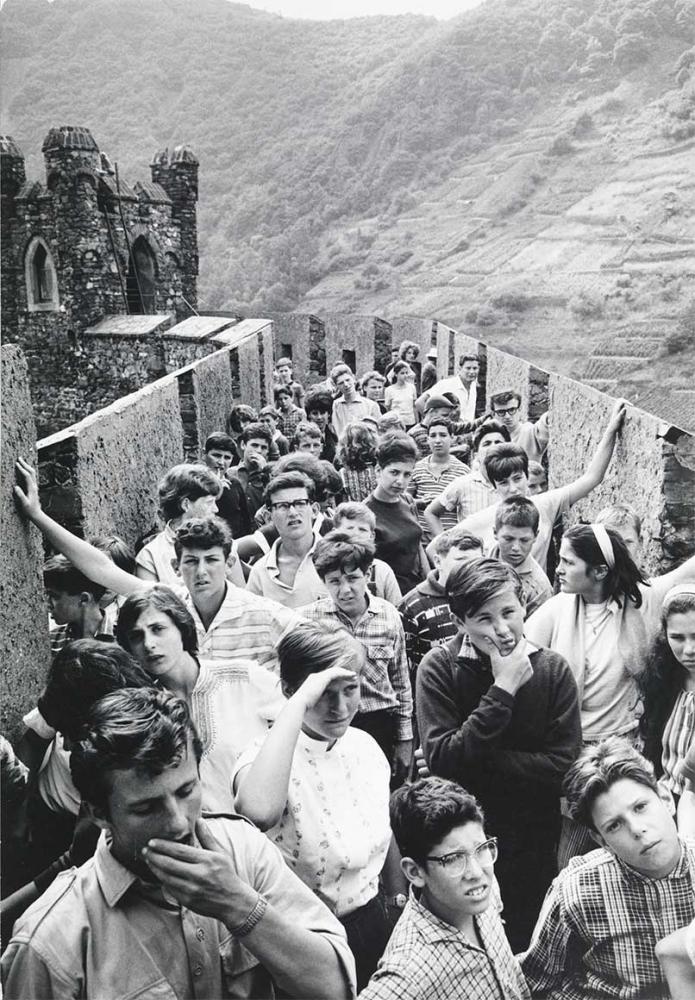

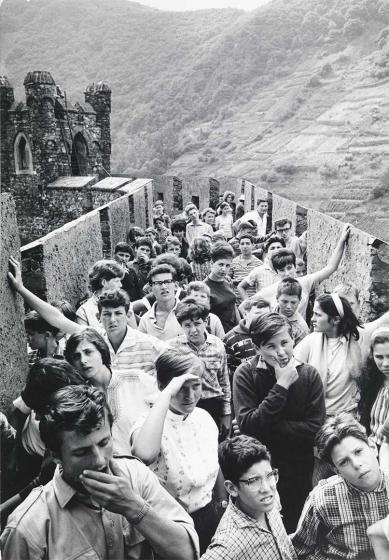

Leonard Freed, A group from the Bad Sobernheim holiday camp on a field trip, Reichenstein Castle, 1961; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2008/305/23.

Further information about this photo can be found in our online collections (in German)

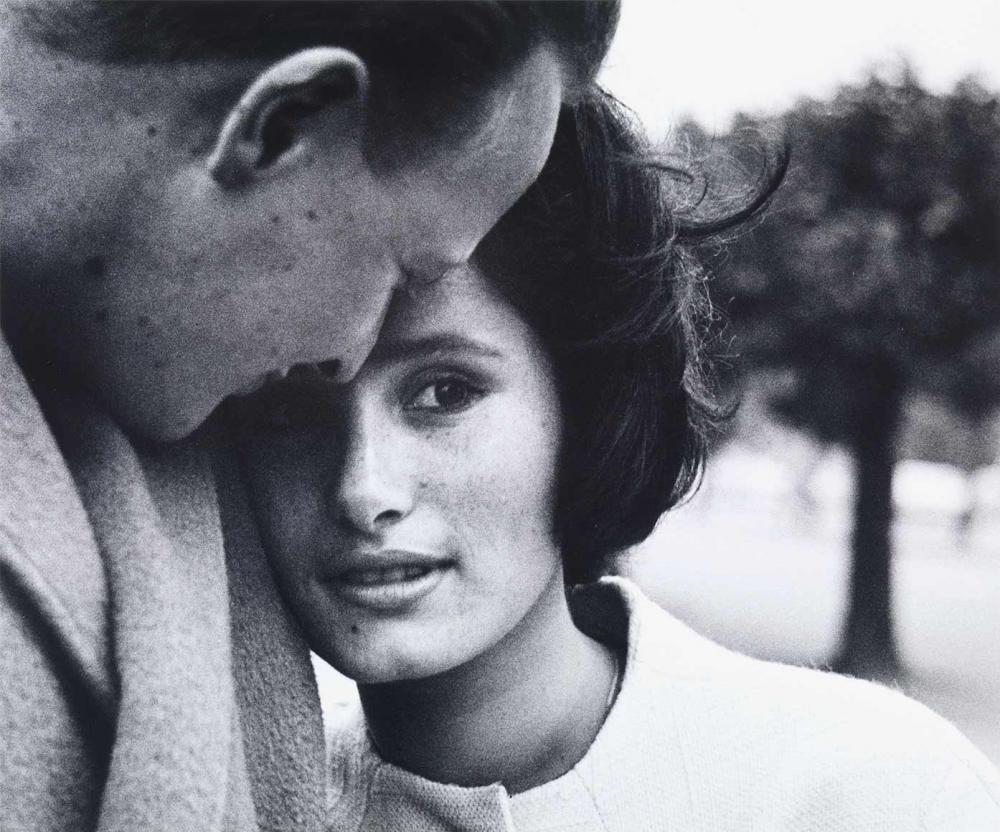

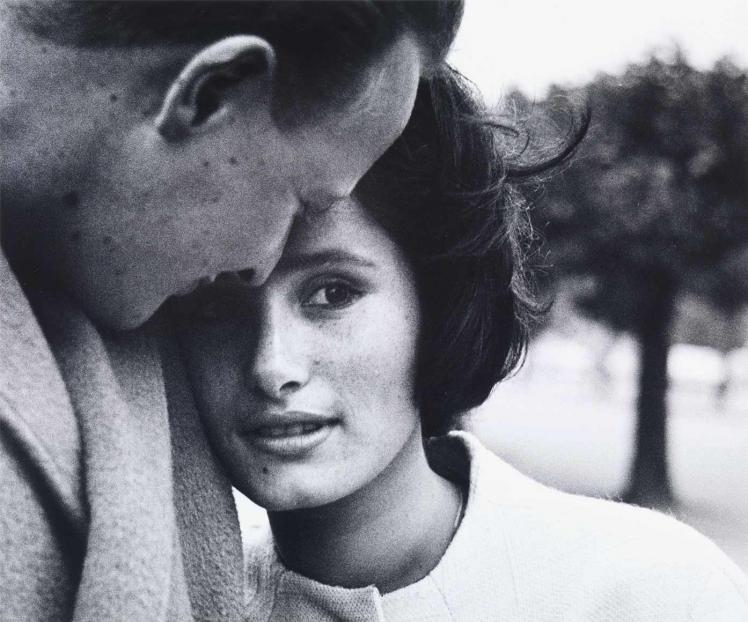

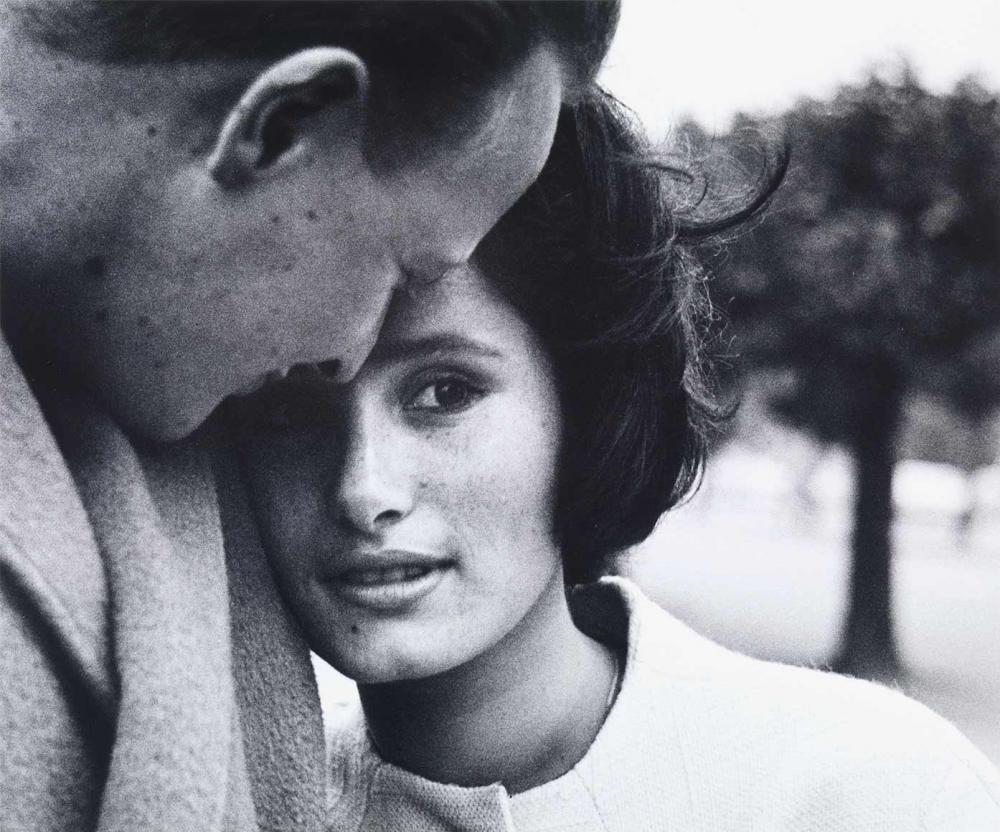

Leonard Freed, Young couple, Düsseldorf, 1961; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2008/305/39.

Further information about this photo can be found in our online collections (in German) as well as in the essay Ruth and Herbert Rubinstein: Two Lives in Düsseldorf further down on this page

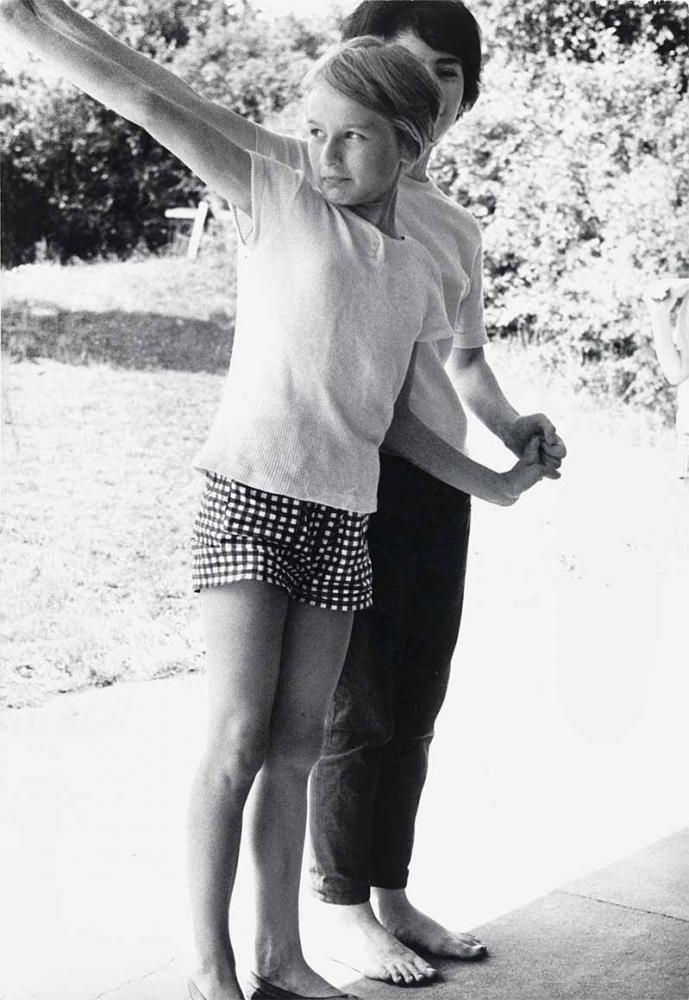

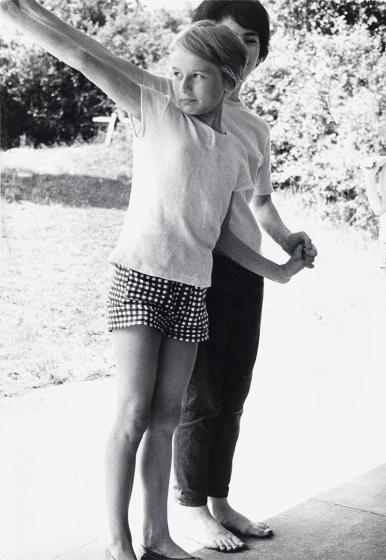

Leonard Freed, Children dancing the Hora at the holiday camp, Bad Sobernheim, 1961; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2008/305/24.

Further information about this photo can be found in our online collections (in German)

Leonard Freed, Children playing, Bad Sobernheim, 1961; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2008/305/25.

Further information about this photo can be found in our online collections (in German)

Leonard Freed, The youth group, Düsseldorf, 1961; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2008/305/26.

Further information about this photo can be found in our online collections (in German)

Leonard Freed, Children at the Makkabi sports club, Düsseldorf, 1961; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2008/305/27.

Further information about this photo can be found in our online collections (in German)

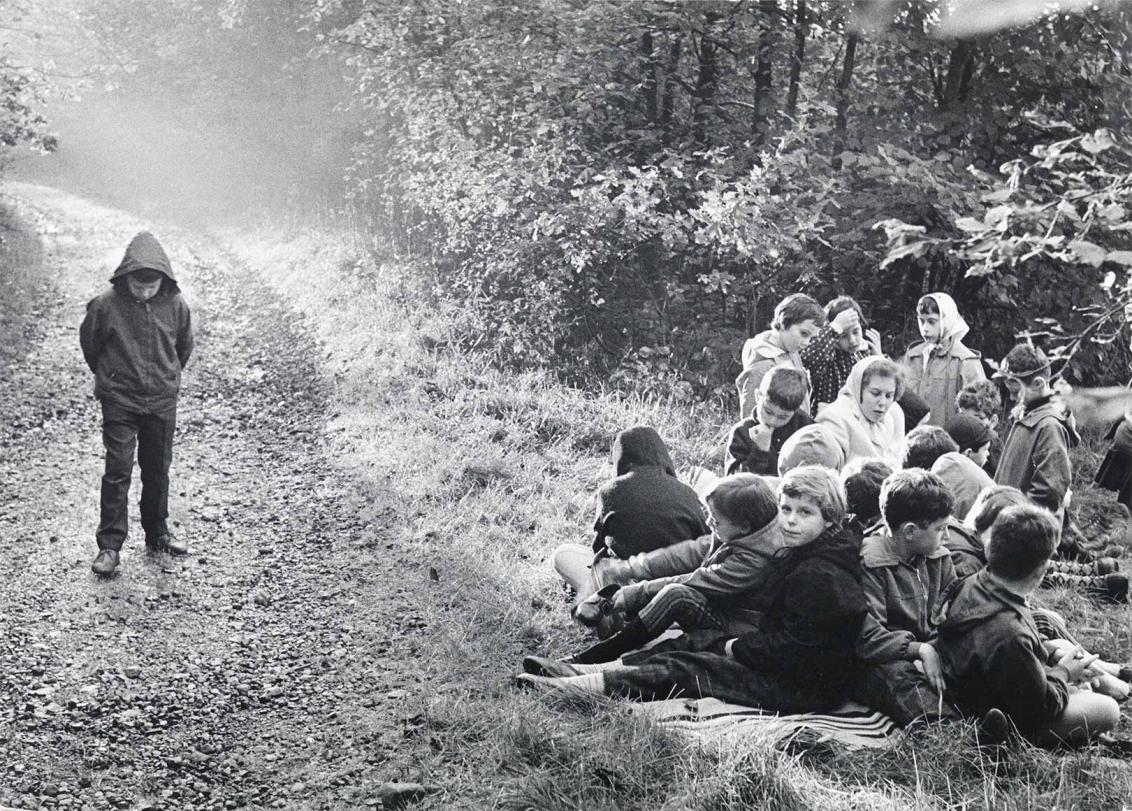

Leonard Freed, Children from Düsseldorf at a school camp, Westerwald, 1961; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2008/305/28.

Further information about this photo can be found in our online collections (in German)

Leonard Freed, Children from Bad Sobernheim on an excursion, Reichenstein Castle, 1961; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2008/305/29.

Further information about this photo can be found in our online collections (in German)

Leonard Freed, Children on an autumn excursion, Westerwald, 1961; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2008/305/30.

Further information about this photo can be found in our online collections (in German)

Essays by the Curators on the Exhibition German Jews Today

Leonard Freed’s Photo Series German Jews Today

In 1961 and 1962, Leonard Freed turned his lens toward the Jewish community of West Germany. It was not his first time focusing on Jewish subject matter. As early as 1954, he had photographed Orthodox Jews in the Williamsburg neighborhood of Brooklyn, New York, where he was born and raised. In 1958, he published his first book, Joden van Amsterdam, containing fifty-two photographs from an extensive series on Jewish life in Amsterdam.

For his project in Germany, Freed primarily took photographs in Frankfurt, Düsseldorf, and the surrounding regions, but also in Bad Sobernheim, Berlin, Dachau, Essen, Hamburg, Cologne, Mainz, Munich, Nuremberg, Offenbach, Warendorf, Worms, the Westerwald mountains, and Reichenstein Castle. Nearly every picture features people – but not as conventional portraits. Rather, the images reflect situations and moods.

Historical Context

The Holocaust was less than twenty years in the past. West Germany’s few Jewish communities were small, with around 25,000 Jews residing in the country altogether. Their presence in the “land of the perpetrators” could not be taken for granted. Most were there for lack of other options, living with “packed suitcases,” as the saying went. Observers abroad were also perplexed by their decision to live in Germany, where antisemitism remained mainstream and the process of reckoning with the legacy of Nazism was only getting started, and at a snail’s pace. After the 1961 Eichmann trial in Jerusalem, two more years went by before the second Auschwitz trials began in Frankfurt. Israel did not establish diplomatic relations with West Germany until 1965. That year, the Bundestag debated whether the statute of limitations for Nazi crimes had expired. Many Germans wished to “draw a line” under the past. In 1966, the World Jewish Congress held a special discussion in Brussels on the theme “Germans and Jews: A Problem Unresolved.” Such an event would have been unthinkable then in Germany.

Freed’s Concern

With his photographs, Leonard Freed sought to counteract Germans’ ignorance about the invisible Jewish minority in their midst. This was an important concern for him, as he observed Germans’ refusal to confront their recent past. This impression was reinforced when he met his future wife Brigitte and visited her at her parents’ home in Dortmund. Alongside this educational motivation, his quest for his own Jewish identity played a formative role in this long-term project.

Realization of the Photo Project

By the early 1960s, Brigitte and Leonard Freed were already living in Amsterdam with their young daughter, Elke Susannah. In order to travel together to different German cities for the photography project, they often left their daughter with her grandparents in Dortmund. Brigitte served as Freed’s interpreter, organized photography appointments, and accompanied her husband during the shoots. Later, she developed prints in the darkroom and labeled the photographs.

Out of several thousand images, Leonard Freed selected fifty-two for the ninety-six-page book, which he published in 1965 under the title German Jews Today. The book was designed by renowned designer Willy Fleckhaus, and essays by prominent Jewish intellectuals accompanied the photographs, juxtaposing powerful writing against Freed’s visuals. For each image, Freed wrote his own captions, some of them quite detailed. Unlike the subjective impressions he recorded in his other books, these captions were written in a neutral and informative style.

The Arrangement of the Photographs

No doubt the sequence of photographs was also deliberate. Leonard Freed’s camera captures both skepticism and hope. The book is divided into five thematic sections linked by accompanying texts. It opens with a panorama, presenting various themes via individual photographs. The very first image depicts marble busts along a wall of the old Jewish cemetery in Frankfurt am Main; the identities of their subjects are unknown. The second photograph shows the Jewish cemetery in Worms, one of the oldest in Europe. Both images highlight the long tradition of Judaism in Germany and the profound rupture the Holocaust represented.

The book includes three images with direct visual references to Nazi atrocities, all of which appear in the first chapter of photographs. The first shows a woman’s arm tattooed with a concentration camp number from Auschwitz; the second, a prayer book containing photographs of murdered family members; and the third, spaced wooden boards over a blood trench at the site of Dachau concentration camp.

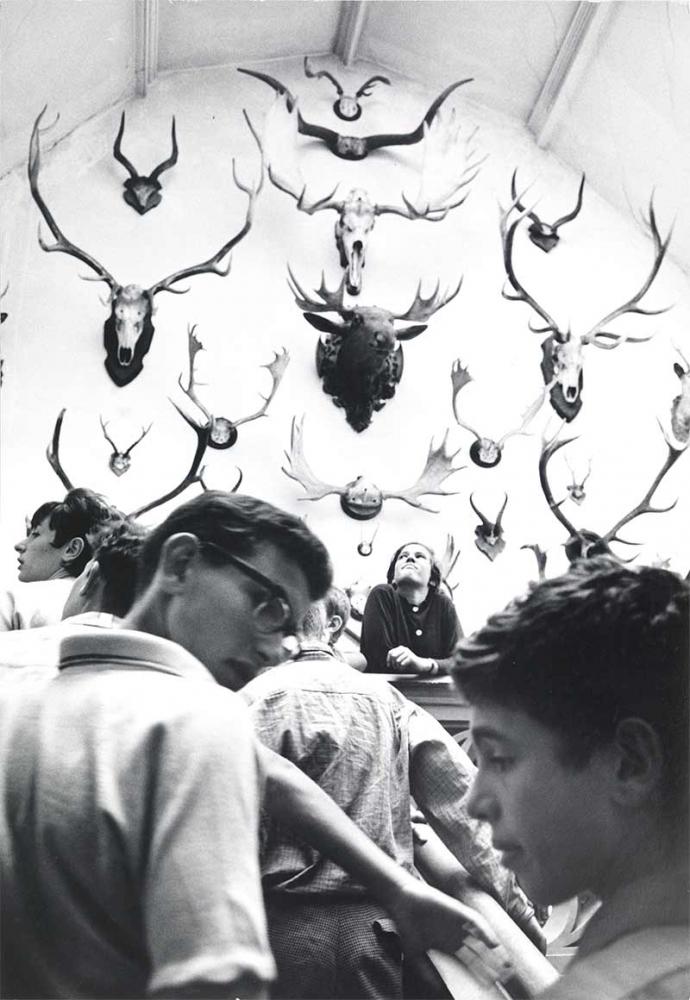

The second group of photographs is dedicated to religious aspects of Jewish communal life, including several images from the Polish-Jewish prayer room in Frankfurt as well as scenes from a Jewish wedding and a Bar Mitzvah. The following section depicts various professions, such as a stonemason, a textile manufacturer, and two scenes from a kosher slaughterhouse. The penultimate section features well-known individuals. Finally, Freed turns his lens to young people, children and teenagers. This conclusion, with its largely open-ended and optimistic images, reinforces the photographer’s hopeful outlook. Freed’s photos are marked by empathy, sensitivity, and seriousness but also have humorous touches.

A US Perspective on Germany

Alongside Jewish themes, Leonard Freed had been photographing other aspects of Germany since the early 1950s, which he compiled in the 1970 book Made in Germany. Freed was fascinated by the country and its people; his introduction wondered what it would look like in twenty-five years. Particularly notable are a series of short texts at the end of the extensive pictorial section, titled Trauma I–IV, which recount personal stories and experiences of prejudice and antisemitism from Freed’s perspective.

Freed later wrote, “I feel being born in the United States gives me a fresh or extra eye to observe what the average German will overlook.”

(fax from Leonard Freed to Ute Eskildsen, 1990; Leonard Freed Archive). This is undoubtedly true of the pictures he took in the 1960s for the German Jews Today series.

Theresia Ziehe, Curator of Photography and of the exhibition

I (Don’t) Live in the Federal Republic

“The rift is still unbridged. There is no going back, because there can be no forgetting and no consolation.”

Manès Sperber (Kesten, p. 156)

X

X

“The rift is still unbridged. There is no going back, because there can be no forgetting and no consolation.”

Manès Sperber (Kesten, p. 156)

In 1964, the Munich-based Paul List Verlag published a paperback whose title ich lebe nicht in der Bundesrepublik translates to I Don’t Live in the Federal Republic – in other words, West Germany. The book was edited by the writer Hermann Kesten, who had fled the Nazi regime in 1933 – first going to France, and later to the United States. A US citizen since 1949, he repeatedly returned to Germany to visit, but never settled back down in his birthplace. The book features contributions from 34 authors, many of them Jews who had emigrated from Germany. As Kesten mentions in the introduction, the book was inspired by another paperback, ich lebe in der Bundesrepublik (I Live in the Federal Republic), which had been edited by journalist Wolfgang Weyrauch and released by the same publisher in 1961. The earlier anthology presented critical self-reflections on Germany by fifteen well-known German authors.

Leonard Freed’s photographs were taken mostly in 1961 or 1962, and his book of photography, Deutsche Juden heute (German Jews Today), was released in 1965 by the Munich publisher Rütten & Loening. The thematically grouped photographs are interwoven with essays by well-known Jewish intellectuals examining the state of Jewish communities in West Germany and the relationship between Jews and Germans. Three of the authors – Hermann Kesten, Ludwig Marcuse, and Robert Neumann – had also contributed to I Don’t Live in the Federal Republic. In his essays for both books, Kesten vividly describes his ambivalent relationship with Germany, which ruled out the prospects of staying for long periods, let alone returning permanently, despite his deep emotional ties to the country.

“During this time, many people asked me: ‘Do you feel more German or Jewish?’ I don’t know what they mean by ‘do you feel?’. But I know for sure that I am above all Jewish, Jewish, Jewish—as long as Jews are persecuted.”

Ludwig Marcuse (Freed, p. 68)

X

X

“During this time, many people asked me: ‘Do you feel more German or Jewish?’ I don’t know what they mean by ‘do you feel?’. But I know for sure that I am above all Jewish, Jewish, Jewish—as long as Jews are persecuted.”

Ludwig Marcuse (Freed, p. 68)

What kind of country was Leonard Freed capturing on film?

These books offer diverse perspectives on the political and social landscape of West Germany, less than twenty years after the Nazi dictatorship. The country had two faces. “The intellectual and moral climate of the Federal Republic of Germany is contradictory and peculiar enough. The contrast between decent, feeling individuals and unfeeling cynics, whether conscious or unconscious, seems sharper than ever,”

Kesten writes in his introduction, “The Eternal Exile”

(Kesten, p. 20). Recurring themes include anti-communism; the Germans’ relentless industriousness paired with the related desire to forget their recent past, and the burgeoning prosperity of West Germany’s “economic miracle,” with its rebuilding of cities devastated by the war. “The whole country appears renovated,”

Kesten remarks (Freed, p. 79).

The Federal Republic of Germany was a liberal democracy with a free press and separation of powers. Yet, alongside committed democrats, former Nazis once again occupied prominent positions. “The murderers are walking around free,”

writes Robert Neumann (Kesten, p. 127). The courts had only begun reckoning with Nazi crimes, and antisemitic attitudes persisted, even though they were officially shunned and punishable by law. At the same time, a kind of philosemitism tinged with guilt was commonplace. The country’s Jewish communities lived “in that atmosphere, a peculiar blend of bad conscience and goodwill,”

as the journalist Hans Hermann Köper, editor of German Jews Today, observed (Kesten, p. 8).

Home on cursed ground?

The weekly news magazine Der Spiegel, which had hundreds of thousands of readers, published a special issue about Jews in Germany on 31 July 1963, addressing all these themes. “Home on cursed ground?”

ran the cover story headline. The issue also included an interview with Hendrik G. van Dam, the Secretary General of the Central Council of Jews in Germany, and an article titled “Antisemitism Among Us?”

written under a pseudonym by Der Spiegel’s publisher, Rudolf Augstein.

“I believe that the Federal Republic of Germany should be politically designed in such a way that Jews can live here as Jews.”

Hendrik van Dam (Der Spiegel, 31 July 1963, the whole interview in German)

X

X

“I believe that the Federal Republic of Germany should be politically designed in such a way that Jews can live here as Jews.”

Hendrik van Dam (Der Spiegel, 31 July 1963, the whole interview in German)

The questions raised in these three publications remain timeless and no less pressing: As a Jew, where do I want to live? Where can I live? Where wouldn’t I live? And why?

Leonore Maier, Curator of Collections and of the exhibition

The New Synagogue in Düsseldorf: A Symbol of the Eternal “Nevertheless”

Eleven of the 52 photographs in the German Jews Today series were taken in Düsseldorf. In the early 1960s, when Leonard Freed took photographs there, the city’s organized Jewish Community had around 1,000 members and was home to some of postwar Germany’s most important Jewish institutions, such as the Allgemeine Wochenzeitung der Juden in Deutschland (General Weekly Newspaper of Jews in Germany) under editor-in-chief Karl Marx (no relation), and the Central Council of Jews in Germany.

Freed primarily focused his camera on individual members of the Jewish community. However, he also took an interest in the place where Düsseldorf’s Jewish residents came together for celebrations, social gatherings, events, and religious services: the newly built synagogue, inaugurated in 1958, and the associated community center. This street view was taken on a sunny summer day in the Golzheim district.

Leonard Freed, New synagogue and new community center, Düsseldorf, 1961; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2008/305/3.

Further information about this photo can be found in our online collections (in German)

X

X

Leonard Freed, New synagogue and new community center, Düsseldorf, 1961; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2008/305/3.

Further information about this photo can be found in our online collections (in German)

The image shows the synagogue at the corner of Zietenstrasse and Mauerstrasse (the community center, behind it, is out of view). The visual symbolism makes clear that this is a Jewish house of worship. Above the closed door is a seven-branched menorah or candelabrum, a central symbol of Judaism. Below it, a Hebrew inscription from Psalm 26:8 reads, “O Lord, I love Your temple abode, the dwelling-place of Your glory.”

To the right, a tall stained-glass window is adorned with the emblems and Hebrew names of the Twelve Tribes of Israel.

In the foreground, children of elementary school age are playing; a teenager strolls past them casually. The surviving contact sheets of this published photograph also show parked Volkswagen Beetles and other cars along Zietenstrasse – status symbols of West Germany’s ongoing “economic miracle.” Yet the apparent tranquility of the quiet residential neighborhood is deceptive: one of the two boys lying prone on the sidewalk, facing each other, is holding a toy gun. And we know that not long after the synagogue was consecrated in 1959, it became the target of swastika graffiti.1

The Papers of Hermann Zvi Guttmann

In 2017, the Jewish Museum Berlin received the personal papers of Hermann Zvi Guttmann, the architect of the Düsseldorf synagogue, as a gift from his family. Visitors to the JMB’s permanent exhibition can explore parts of the collection digitally through the interactive Family Album display.

The collection includes extensive materials related to the design and construction of the synagogue and its adjacent community center, as well as documentation and media coverage of the consecration. This treasure trove is closely linked to Leonard Freed’s photograph, which was taken less than three years after the consecration ceremony in the summer of 1961.

Hermann Zvi Guttmann, Street view of the Düsseldorf Synagogue, Frankfurt am Main, ca. 1954–1958, diazo print, gouache, watercolors; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2017/311/406, gift of Dr. Gitta Guttmann and Dr. Rosa Guttmann.

Further information about this object can be found in our online collections (in German)

X

X

Hermann Zvi Guttmann, Street view of the Düsseldorf Synagogue, Frankfurt am Main, ca. 1954–1958, diazo print, gouache, watercolors; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2017/311/406, gift of Dr. Gitta Guttmann and Dr. Rosa Guttmann.

Further information about this object can be found in our online collections (in German)

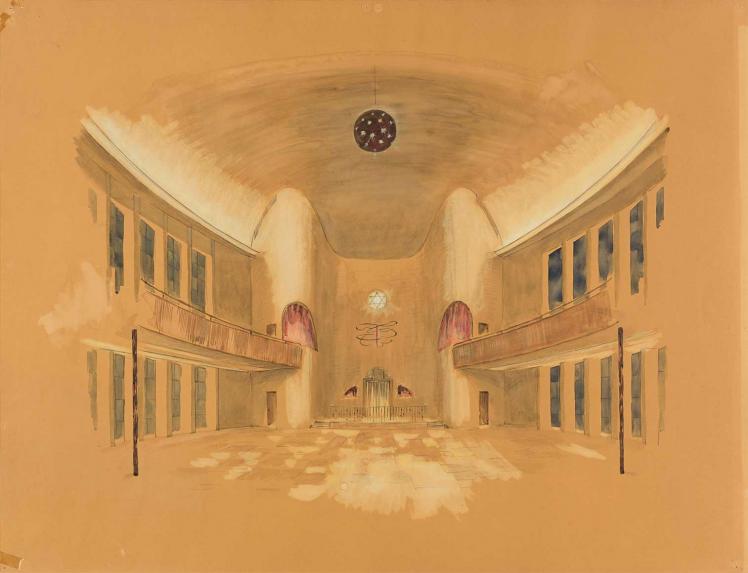

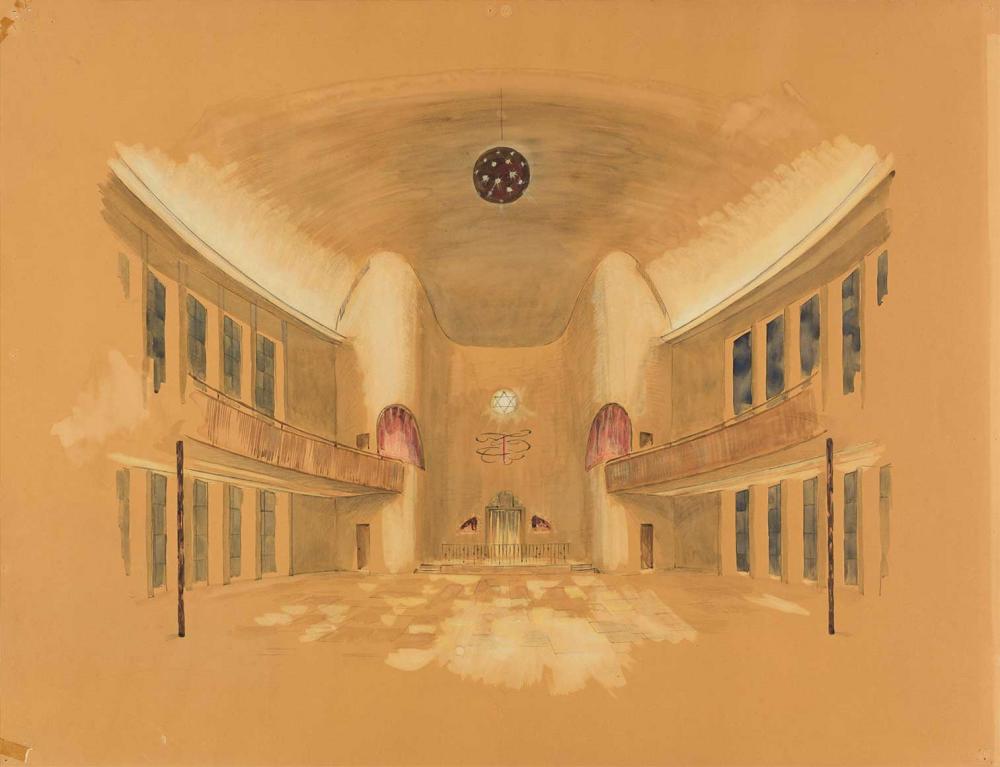

Hermann Zvi Guttmann, Perspective of the Interior of the Düsseldorf Synagogue, Frankfurt am Main, ca. 1953–1962, watercolor on diazo print paper; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2017/311/404, gift of Dr. Gitta Guttmann and Dr. Rosa Guttmann.

The synagogue has approximately 400 seats: 250 on the ground floor for men and another 150 upstairs in the surrounding women’s galleries. Further information about this object can be found in our online collections (in German)

X

X

Hermann Zvi Guttmann, Perspective of the Interior of the Düsseldorf Synagogue, Frankfurt am Main, ca. 1953–1962, watercolor on diazo print paper; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2017/311/404, gift of Dr. Gitta Guttmann and Dr. Rosa Guttmann.

The synagogue has approximately 400 seats: 250 on the ground floor for men and another 150 upstairs in the surrounding women’s galleries. Further information about this object can be found in our online collections (in German)

Leonard Freed, Before service in the synagogue, Düsseldorf, 1961; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2008/305/17.

One of the women’s galleries is partially visible in this image. Further information about this photo can be found in our online collections (in German)

X

X

Leonard Freed, Before service in the synagogue, Düsseldorf, 1961; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2008/305/17.

One of the women’s galleries is partially visible in this image. Further information about this photo can be found in our online collections (in German)

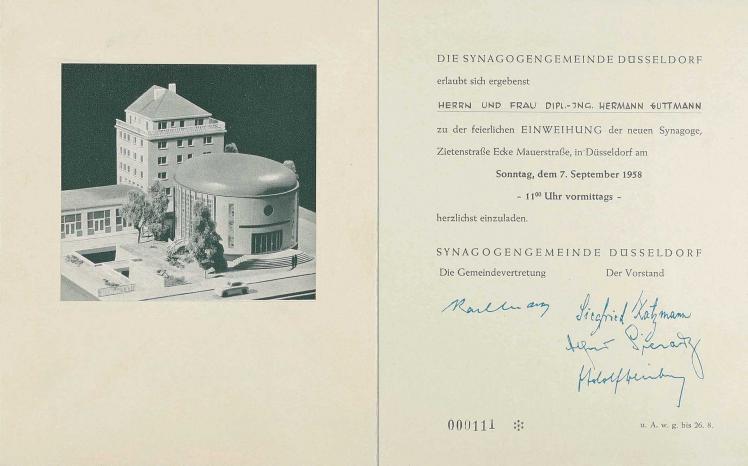

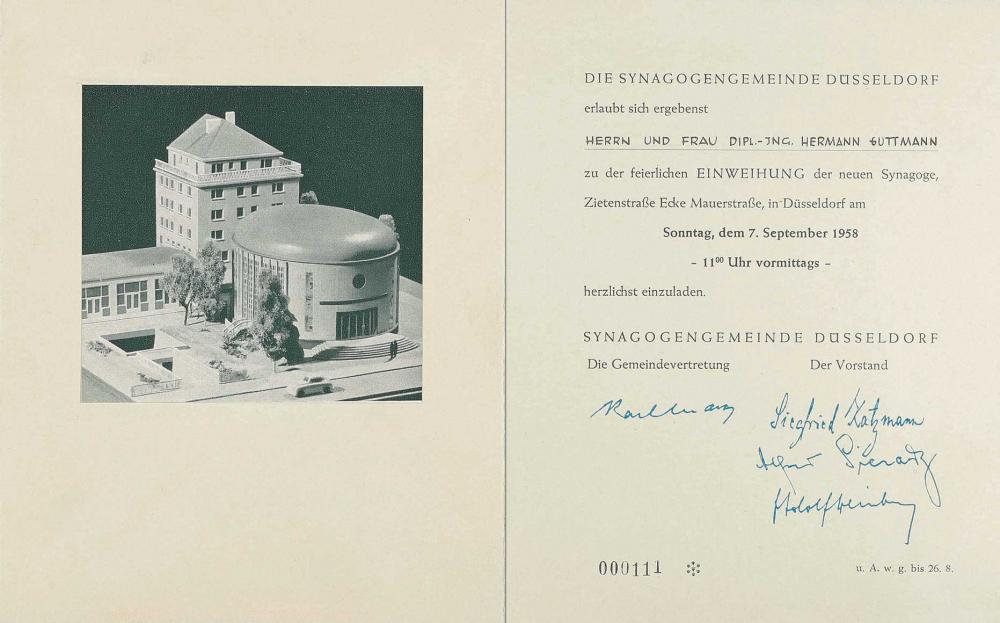

The synagogue’s consecration ceremony on 7 September 1958 is exceptionally well-documented among Guttmann’s papers. This includes the synagogue’s invitation card to Mr. and Mrs. Guttmann, featuring an illustration of the entire building complex, as well as the brochure Die neue Synagoge in Düsseldorf (The New Synagogue in Düsseldorf), which contains messages from politicians – including West Germany’s Chancellor Konrad Adenauer – as well as Jewish representatives, each reflecting on the significance of the synagogue’s construction nearly twenty years after the “Kristallnacht” pogroms and the destruction of the old synagogue.

Front (left) and inside (right) of the invitation card for the synagogue’s consecration, addressed to architect Hermann Guttmann and his wife, 7 September 1958; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2017/309/196, gift of Dr. Gitta Guttmann and Dr. Rosa Guttmann.

The invitation reads: “The Düsseldorf Synagogue Congregation cordially invites Mr. and Mrs. Hermann Guttmann, certified engineer, to the formal consecration of the new synagogue at the corner of Zietenstrasse and Mauerstrasse in Düsseldorf on Sunday, 7 September 1958 – 11:00 a.m.”

X

X

Front (left) and inside (right) of the invitation card for the synagogue’s consecration, addressed to architect Hermann Guttmann and his wife, 7 September 1958; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2017/309/196, gift of Dr. Gitta Guttmann and Dr. Rosa Guttmann.

The invitation reads: “The Düsseldorf Synagogue Congregation cordially invites Mr. and Mrs. Hermann Guttmann, certified engineer, to the formal consecration of the new synagogue at the corner of Zietenstrasse and Mauerstrasse in Düsseldorf on Sunday, 7 September 1958 – 11:00 a.m.”

Chancellor Adenauer’s congratulatory message invoked the “successes” of West German “reparation policies” in lights of the re-emergence of Jewish houses of worship. Meanwhile, Hendrik van Dam, a representative of the Central Council of Jews in Germany, quoted Rabbi Leo Baeck’s notion of the eternal dennoch (“nevertheless”) as a running theme of Jewish history. In the immediate aftermath of the Shoah, it seemed unthinkable that synagogues would be rebuilt and Jewish communities would have a lasting presence in Germany. In an article titled “A Testament to Survival: What Does the Consecration of a Synagogue Mean?” and published on 5 September 1958, Karl Marx, editor-in-chief of the Allgemeine Wochenzeitung der Juden in Deutschland, wrote:

“Today, there is no longer any doubt about the future of Judaism in Germany – just as there is no doubt about the past. Knowing that we cannot simply continue where the threads were abruptly cut, we have resolved to shape the present with remembrance of the past. … All that matters is the fact that Jews have a future in Germany.”

Despite the stark differences in their perspectives, all these texts bear witness to the profound symbolic significance attributed to the new Düsseldorf synagogue and its community center in the rebuilding of Jewish life in Germany after the Shoah.

Leonore Maier, Curator of Collections and of the exhibition

On 7 September 2023, the Jewish Community of Düsseldorf released this film by Zeev Reichard commemorating the 65th anniversary of the synagogue’s inauguration, which presents the synagogue in great visual and informative detail (in German).

- City of Düsseldorf, Mayor’s Office, Stadtmuseum, ed. Von Augenblick zu Augenblick. Juden in Düsseldorf nach 1945 (From Moment to Moment: Jews in Düsseldorf after 1945), chapter on antisemitism. ↩︎

Ruth and Herbert Rubinstein: Two Lives in Düsseldorf

Leonard Freed, Young couple, Düsseldorf, 1961; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2008/305/39.

Further information about this photo can be found in our online collections (in German)

X

X

Leonard Freed, Young couple, Düsseldorf, 1961; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2008/305/39.

Further information about this photo can be found in our online collections (in German)

The photograph shows a young man and woman in an intimate pose with their faces close together, just as Leonard Freed captured them in Düsseldorf in 1961. In 2015, this print was displayed at the Stadtmuseum Düsseldorf as part of the exhibition Von Augenblick zu Augenblick – Juden in Düsseldorf nach 1945 (From Moment to Moment: Jews in Düsseldorf after 1945), on loan from the Jewish Museum Berlin along with other photographs from the German Jews Today series.

During the preparations for that exhibition, the previously anonymous couple was finally identified: Ruth and Herbert Rubinstein. They are both still living in Düsseldorf today and have since maintained a close relationship with the Jewish Museum Berlin for several years.

Ruth Rubinstein

Ruth Rubinstein was born in 1942 in Tel Aviv and grew up in nearby Herzliya. Her mother was from Bad Nauheim, outside Frankfurt, and her father grew up in Cologne, but the two met in Palestine, where they started a family. They ran a small grocery store, but life was difficult, and after suffering multiple heart attacks, her father realized that he could no longer risk his health.

So, in the autumn of 1956, the family relocated to Cologne, her father’s birthplace. At the time, Ruth was 15 years old. She did not want to leave Israel and could not understand why her parents would choose to return to Germany, of all places. She and her sister, who was four years younger, were not allowed to tell anyone about the move. They left the country without saying goodbye – an especially painful experience for Ruth.

In Cologne, the family lived across the street from the synagogue on Roonstrasse, which was reconsecrated in 1959. Through the window, Ruth could see the synagogue. She spent much of her free time there, singing in the choir and taking part in activities at the youth center. Her dedication to the Jewish community would remain a constant throughout her life. Her parents ran three menswear shops in Cologne. She helped out there occasionally, but ultimately became a kindergarten teacher.

Herbert Rubinstein

Herbert Rubinstein was born in 1936 in the city of Czernowitz, which was then in Romania and is now Chernivtsi, Ukraine. He and his mother survived the Holocaust, but his father was shot by the Nazis in 1945.

After the war, his mother met Auschwitz survivor Max Rubin, who was originally from Düsseldorf. The new couple brought Herbert to Amsterdam, where they married. In 1956, Herbert relocated with his mother and stepfather to Düsseldorf. The family started small. Max Rubin had a business manufacturing women’s belts.

Herbert also cherished the companionship of his fellow Jews and became very active in youth work for the Jewish Community.

A Life Together

Ruth and Herbert Rubinstein met at a Hanukkah ball in Düsseldorf. Herbert was attending with his best friend, Paul Spiegel; Ruth had come from Cologne. They danced together – a moment that would change their lives.

In 1964, they were legally married at the registry office in Düsseldorf, followed shortly after by a Jewish wedding at the synagogue on Roonstrasse in Cologne. They soon moved to Düsseldorf, where their daughter was born in 1965, followed by twin sons in 1972.

Jewish friends and neighbors remained a strong source of support for them as a family, and to this day, they remain deeply involved in Jewish life in Düsseldorf. Ruth Rubinstein is the honorary chair of the local Jewish Community and served on its board for more than twenty years. Herbert Rubinstein also serves on the Community’s board and continues to speak as an eyewitness to history and Holocaust survivor, frequently sharing his wartime experiences with schoolchildren.

The Rubinstein couple, Düsseldorf, 2018; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2018/314/0, photo: Stephan Pramme

X

X

The Rubinstein couple, Düsseldorf, 2018; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2018/314/0, photo: Stephan Pramme

The Rubinsteins and the JMB

For the 2018 Jewish Museum Berlin exhibition A Is for Jewish: Journeys through Now in 22 Letters, the couple was photographed again, fifty-seven years after Leonard Freed’s original image. This time photographer Stephan Pramme captured them in a nearly identical pose at the same location: the Rhine Promenade in Düsseldorf.

For the current exhibition German Jews Today. Leonard Freed, Ruth and Herbert Rubinstein provided the museum with key details about the people and situations depicted in Freed’s photo series. Their contributions have recontextualized the fifty-two images, assembling biographical details and personal experiences of the individuals portrayed.

Ruth and Herbert Rubinstein looking at the photo book German Jews Today by Leonard Freed; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession Presse/3136/2, photo: Theresia Ziehe

X

X

Ruth and Herbert Rubinstein looking at the photo book German Jews Today by Leonard Freed; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession Presse/3136/2, photo: Theresia Ziehe

At the end of 2024, they visited the exhibition with their family, now including three children, four grandchildren, and two great-grandchildren. Not all of them could attend, but four generations were represented.

As in 2018, this new encounter with the couple was deeply moving. They had recently celebrated their diamond wedding anniversary, and each describes the other as their greatest stroke of luck; their deep appreciation for each other is palpable. Herbert Rubinstein calls his wife “the best woman in the world.”

In turn, Ruth shared a story about her father. Once, when she asked why their family had left Israel, her father responded, “If we hadn’t emigrated, you never would have met this golden treasure.”

Ruth and Herbert Rubinstein in the exhibition German Jews Today. Leonard Freed; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession Presse/3136/1, photo: Theresia Ziehe

X

X

Ruth and Herbert Rubinstein in the exhibition German Jews Today. Leonard Freed; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession Presse/3136/1, photo: Theresia Ziehe

Theresia Ziehe, Curator of Photography and of the exhibition

“Another Book About the Jews?”

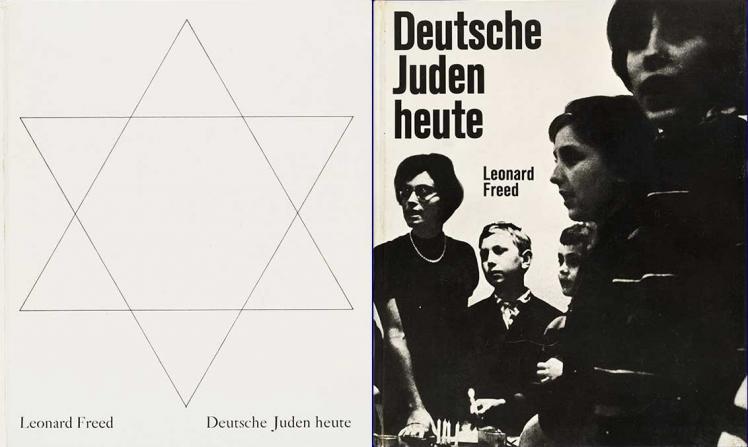

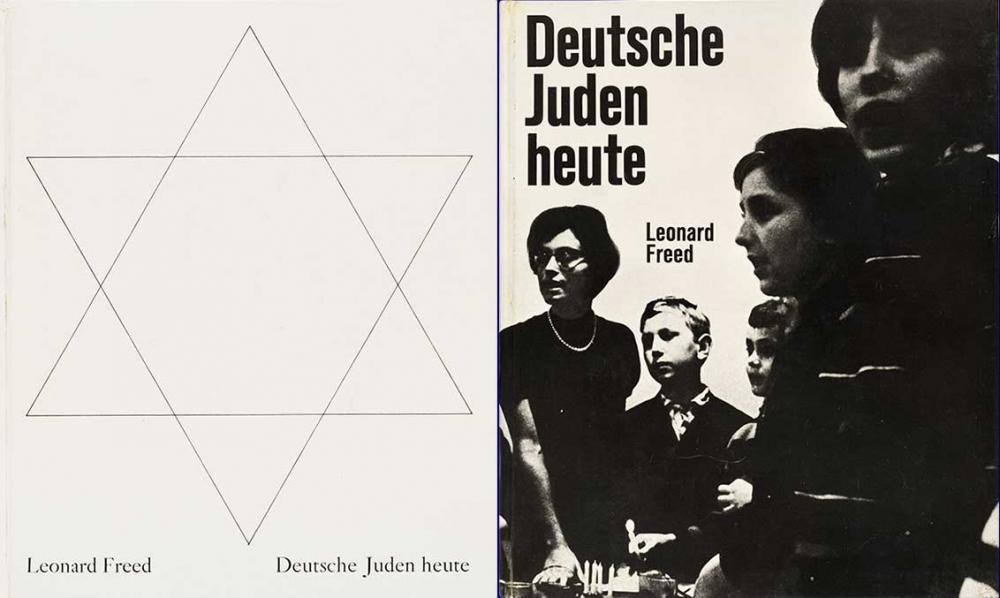

A closer look at the publication history of Deutsche Juden heute (German Jews Today) reveals surprising links among the people involved behind the scenes. While developing his book project, Leonard Freed came across individuals who were committed to countering historical amnesia and educating the German public. The original edition of German Jews Today, with a cover designed by Willy Fleckhaus, was published in 1965 by Rütten & Loening. It won an award as one of the most beautiful books of the year and exhibited at the Frankfurt Book Fair.

Shortly thereafter, the book was reprinted as a “licensed edition” from the Bertelsmann Lesering mail-order book club. This edition had a larger print run than the version sold in bookstores – 10,000 compared to the original 2,000 copies – and cost half the price. The dust jacket now featured a photograph from Freed’s series showing children and young people celebrating Hanukkah. The book club catered to a wide-ranging, mass audience, with 2.5 million members in 1960.

Cover of the first edition (left) and the Bertelsmann Lesering book club edition (right) of German Jews Today

X

X

Cover of the first edition (left) and the Bertelsmann Lesering book club edition (right) of German Jews Today

In 1966, the first and second quarterly issues of the Lesering-Illustrierte (the book club’s illustrated catalog/magazine) promoted the licensed edition as a new release. The lengthy blurb opened with the question “Another book about the Jews?”

, referencing widespread antisemitic attitudes, and recommended the book as a “vivid testament to a living minority: the German Jews of today.”

Page from the Lesering-Illustrierte catalog, 1st quarter, March 1966, featuring an blurb for German Jews Today by Leonard Freed.

The blurb reads:

Leonard Freed

German Jews Today95 pages on coated paper, including 21 pages of text and 65 pages of 52 black-and-white photographs. Large format 20.6 x 25 cm. Hardcover

“Another book about the Jews?” some readers may ask themselves at first, only to discover with some surprise that the authors of this book would almost agree. They state in no uncertain terms that overly desperate efforts to address the subject have done nothing to the few Jews still living in Germany – roughly 21,000 of them – in fact, they assert that the officially sanctioned and enthusiastically practiced philosemitism actually revives old resentments and turns the Jews once again into a warily watched minority.

“We don’t want special treatment,”Robert Neumann writes in his essay,“not Himmler’s version and not the version that handles us like raw eggs and wants to gold-plate us. The only right I claim for us is the right to sin: to park illegally like any other driver, then later, to palm off a run-down car with undisclosed flaws on some hapless buyer like anyone else, to rant drunkenly in the street at night, or even commit robbery or murder – and yet hear from others that it was Meier who did it, not Meier the Jew... Only then, I believe, will antisemitism in Germany be over.”The quiet, human images in this book speak for themselves and, together with the idiosyncratic essays, form a vivid testament to a living minority: the German Jews today.

Item no. 1489

Discounted price: 11 DM

X

X

Page from the Lesering-Illustrierte catalog, 1st quarter, March 1966, featuring an blurb for German Jews Today by Leonard Freed.

The blurb reads:

Leonard Freed

German Jews Today95 pages on coated paper, including 21 pages of text and 65 pages of 52 black-and-white photographs. Large format 20.6 x 25 cm. Hardcover

“Another book about the Jews?” some readers may ask themselves at first, only to discover with some surprise that the authors of this book would almost agree. They state in no uncertain terms that overly desperate efforts to address the subject have done nothing to the few Jews still living in Germany – roughly 21,000 of them – in fact, they assert that the officially sanctioned and enthusiastically practiced philosemitism actually revives old resentments and turns the Jews once again into a warily watched minority.

“We don’t want special treatment,”Robert Neumann writes in his essay,“not Himmler’s version and not the version that handles us like raw eggs and wants to gold-plate us. The only right I claim for us is the right to sin: to park illegally like any other driver, then later, to palm off a run-down car with undisclosed flaws on some hapless buyer like anyone else, to rant drunkenly in the street at night, or even commit robbery or murder – and yet hear from others that it was Meier who did it, not Meier the Jew... Only then, I believe, will antisemitism in Germany be over.”The quiet, human images in this book speak for themselves and, together with the idiosyncratic essays, form a vivid testament to a living minority: the German Jews today.

Item no. 1489

Discounted price: 11 DM

How did German Jews Today get published—and who was involved?

The Literary Agent, Hein Kohn

The book’s backstory began with Freed’s first book and photo project in Amsterdam, where he had lived since 1957. For a year, he photographed the city’s Jewish community. The resulting book, Joden van Amsterdam (Jews of Amsterdam), with text by a journalist from the Algemeen Handelsblad, was published in late 1958 and received considerable public attention in the Netherlands. This success likely inspired the idea of undertaking a similar project in Germany. Perhaps that was when the publisher and literary agent Hein Kohn came into play. His name appeared in 1961 as an intermediary in the licensing agreement between Leonard Freed and the publishing house Rütten & Loening.1

Kohn had fled Germany for the Netherlands in 1933 and went on to become an important figure and bridge-builder in the German-Dutch publishing world. Rütten & Loening and the authors of the essays included in Freed’s book were part of Kohn’s professional network and that of his Internationaal Literatuur Bureau, established in 1951. We do not know when or under what circumstances the photographer and Kohn first met, but it seems quite likely that Kohn played an instrumental role in initiating Freed’s book project, which paired images with essays.

The Program Director, Karl Ludwig Leonhardt

Another key figure whose name and signature appeared on the licensing contract was Karl Ludwig Leonhardt, managing director of Rütten & Loening (which had been part of the Bertelsmann publishing group since 1960) and was also the lead editor of the Bertelsmann Lesering book club. He represented generational shift in leadership at the publishing house and was responsible for including titles in the catalog that critically engaged with the Nazi past. For example, the book club had published The Diary of Anne Frank in 1958, when the subject was still largely taboo in German society. In 1960, Gerhard Schoenberner’s groundbreaking book The Yellow Star, with harrowing photographs of the persecution of Jews in Europe, appeared in a print run of 100,000 copies.2

When Leonard Freed’s book was published, the book club’s catalog was also promoting several other titles that confronted recent history: Wir haben es gesehen (We saw it), a collection of documents and eyewitness accounts of the persecution of Jews during the Third Reich; the memoirs of Max Tau, who had fled Germany for Norway; novels by Leon Uris; and journalistic travelogues about the partition of Germany.

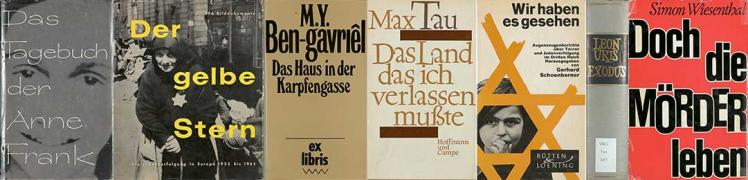

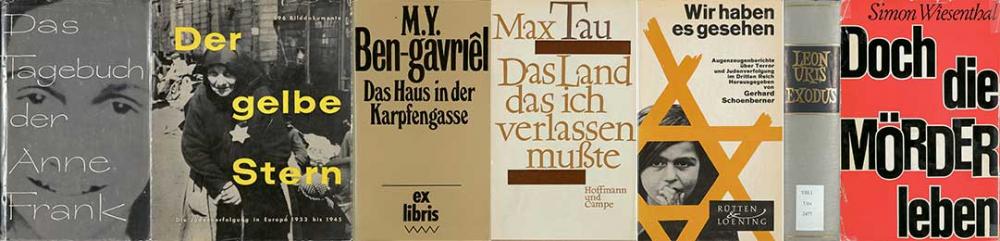

The Jewish Museum Berlin only holds a few exceptional licensed editions from the Bertelsmann Lesering in its collection. Shown here is a selection of book titles from the JMB library that were part of the Lesering catalogue. Each title is followed by the year in which it was announced as a new release in the Lesering-Illustrierte, with a detailed summary (from left to right): Anne Frank, The Diary of Anne Frank (1958); Gerhard Schoenberner, The Yellow Star (1961); Moscheh Ya’akov Ben-Gavriêl, The House on Karpfgasse (1962); Max Tau, The Country I Had to Leave (1964); Gerhard Schoenberner (ed.), We Saw It (1964); Leon Uris, Exodus (1965) ; Simon Wiesenthal, But the Murderers Live (1968).

X

X

The Jewish Museum Berlin only holds a few exceptional licensed editions from the Bertelsmann Lesering in its collection. Shown here is a selection of book titles from the JMB library that were part of the Lesering catalogue. Each title is followed by the year in which it was announced as a new release in the Lesering-Illustrierte, with a detailed summary (from left to right): Anne Frank, The Diary of Anne Frank (1958); Gerhard Schoenberner, The Yellow Star (1961); Moscheh Ya’akov Ben-Gavriêl, The House on Karpfgasse (1962); Max Tau, The Country I Had to Leave (1964); Gerhard Schoenberner (ed.), We Saw It (1964); Leon Uris, Exodus (1965) ; Simon Wiesenthal, But the Murderers Live (1968).

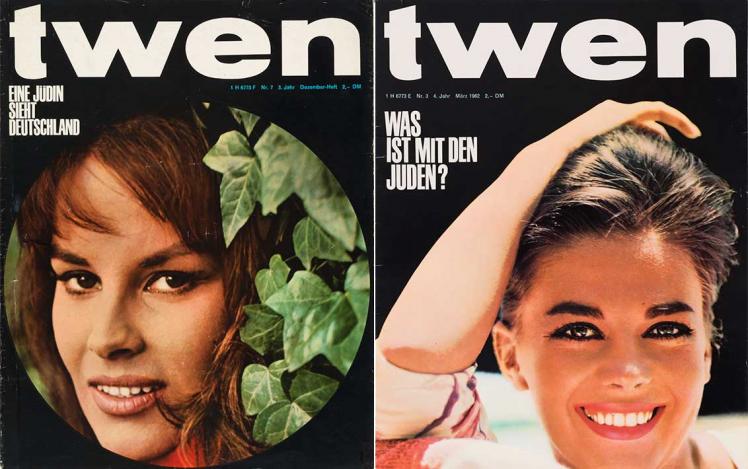

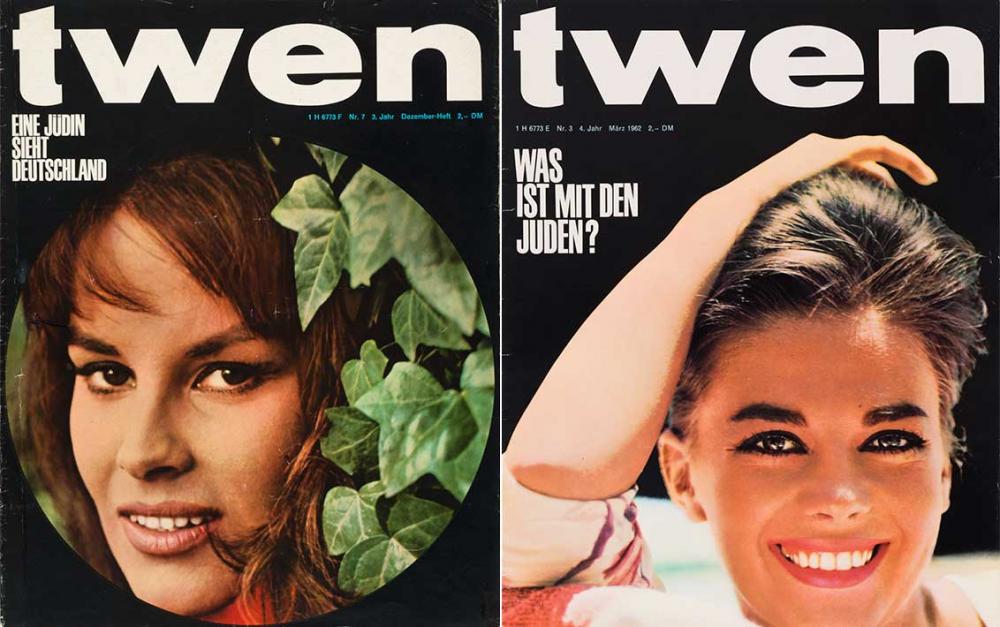

The Magazine, twen

Other figures who shaped the tone and look of German Jews Today included the journalist Hermann Köper and the designer Willy Fleckhaus. Both were associated with a magazine called twen. Fleckhaus had co-founded the magazine in 1959 and was responsible for its distinctive design, while Köper wrote articles to twen. For German Jews Today, he served as co-editor, responsible for copy-editing the text and writing the introduction.

Covers of twen magazine: on the left, the headline that translates as “A Jewish Woman Looks at Germany” (twen, vol. 3 (1961), issue 7); on the right, “What About the Jews?” (twen, vol. 4 (1962), issue 3)

X

X

Covers of twen magazine: on the left, the headline that translates as “A Jewish Woman Looks at Germany” (twen, vol. 3 (1961), issue 7); on the right, “What About the Jews?” (twen, vol. 4 (1962), issue 3)

As a magazine, twen targeted a younger readership and, besides “lifestyle” topics, also reported on social and political issues. In two issues from the early 1960s – around the time when Freed was taking photographs in Germany – the magazine ran cover stories with the headlines “A Jewish Woman Looks at Germany”

and “What About the Jews?”

, foregrounding German attitudes toward Jewish people. The overwhelmingly antisemitic responses to Mary Lea Meyersohn’s article Can One Live in Germany? were printed alongside the editors’ comments in a subsequent issue.3

German Jews Today remained in the Bertelsmann catalogue for three years, until 1968, during which more than 4,000 copies of both editions were sold.

Leonore Maier, Curator of Collections and of the Exhibition

- Contract dated 23 November 1961, Bertelsmann Unternehmensarchiv (corporate archive), reference no. 0011/17. The author is grateful to Mr. Knura from the Bertelsmann Unternehmensarchiv for his kind research support.↩︎

- Siegfried Lokatis. Ein Konzept geht um die Welt. Vom Lesering zur Internationalisierung des Clubgeschäfts, [A concept heard around the word: From the Lesering to Internationalizing the Club Business] in: Bertelsmann AG, ed. 175 Jahre Bertelsmann. Eine Zukunftsgeschichte [175 years of Bertelsmann: A history of the future], Munich: Bertelsmann, 2010, pp. 144ff. ↩︎

- twen, vol. 3 (1961), issue 7, incl. Mary Lea Meyersohn. Kann man in Deutschland leben? [Can one live in Germany?], pp. 32–37; and twen, vol. 4 (1962), issue 3: Was ist mit den Juden? Twen antwortet auf graue Leserbriefe. [What’s the story with the Jews? Twen responds to appalling letters from readers]. ↩︎

Exhibition German Jews Today. Leonard Freed: Features & Programs

- Exhibition Webpage

- Current page: German Jews Today. Leonard Freed – 11 Nov 2024 to 27 Apr 2025, featuring all photos from the exhibition and essays by the curators

- Accompanying Events

- Curator’s tour: Thu 23 Jan & 13 Feb & 13 & 27 Mar & 10 Apr 2025, 4 pm, in German

- “German Jews Today” – a discussion from the 1960s – Panel discussion on 18 Mar 2025, in German

Exhibition Information at a Glance

- When 11 Nov 2024 to 27 Apr 2025

- Entry Fee Free of charge. You can book tickets for a specific time slot online before your visit at our ticket shop, or in person at the ticket counter.

- Where Libeskind Building, ground level, Eric F. Ross Galerie

Lindenstraße 9–14, 10969 Berlin

See Location on Map

Credits

Curators

Leonore Maier

Theresia Ziehe

Project Management

Daniel Ihde

Graphic Design

Team Mao, Berlin (Siyu Mao und Björn Giesecke)

Web Page

Dagmar Ganßloser

Marketing & Communication

Sandra Hollmann

Marketing Campaign Design

bürominimal / Hanno Dannenfeld and Kristina Friske

Graphics Production

Fotoreklame Gesellschaft für Werbung FRG mbH

Art Handling and Exhibition Maintenance

Leitwerk Servicing

Translations

Jake Schneider

SprachUnion

X

X