“The museum is a storehouse of memories”

Embroidered traditional blouses, ca. 1920–1930, gift of Cornelia Hahn Oberlander, 2021

Traditional blouses; Jewish Museum Berlin, gift of Cornelia Hahn Oberlander, photo: Roman März

Shortly before her death, Cornelia Hahn Oberlander gifted the Jewish Museum Berlin three traditional blouses that she and her sister Charlotte wore during their childhood in Berlin. The sisters first established contact with the museum in the mid-1990s. A painting of them dressed in these garments was acquired by the museum; the blouses themselves arrived a quarter century later. The collection curators Inka Bertz and Leonore Maier share the story behind these objects and illuminate what such stories can tell us about donors and the donation process. They also explain why certain details – like a precarious signature on a contract – can be unexpectedly moving.

Among your acquisitions for 2021 are three traditional blouses. What makes these blouses special?

Leonore Maier: Two of the blouses appear in a double portrait of Cornelia Hahn and her sister, Charlotte. The painting dates from 1932 and has been in the collection of the Jewish Museum Berlin since 1997. It was acquired by the museum in the time before the Libeskind Building opened. Almost 25 years later, in the fall of 2020, Cornelia Hahn Oberlander, then 99 years old, offered the blouses to the museum as a gift via her daughter Wendy Oberlander.

Can you tell us a bit more about the blouses?

Maier: The sisters’ father brought the blouses back from a business trip to Romania in the early 1930s. They were being sold to tourists as souvenirs. The plain blouses were mass-produced items, but their embroidered designs, the intricate handiwork of Romanian women, are unique.

Sabine Lepsius, Double portrait of Cornelia Hahn and her sister, Charlotte, Berlin 1932, oil on canvas, 80,5 x 85,5 cm; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession GEM 96/3/0, photo: Jens Ziehe. Further information on this portrait can be found in our online collections (in German)

X

X

Sabine Lepsius, Double portrait of Cornelia Hahn and her sister, Charlotte, Berlin 1932, oil on canvas, 80,5 x 85,5 cm; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession GEM 96/3/0, photo: Jens Ziehe. Further information on this portrait can be found in our online collections (in German)

Charlotte Hahn recorded a detailed memory of how this double portrait came into being (see illustration). In 1932, Sabine Lepsius painted the sisters at their family home in Berlin-Zehlendorf-Steinstücken. What else do we know about the origin of the portrait?

Inka Bertz: I can’t add much to what Charlotte has so vividly written. But I would like to point out that the painting was done in a garden setting. Gardens were always of great importance to the family. The mother, Beate Hahn, was an author of gardening books for children. The family garden was designed by Karl Foerster, a famous garden architect of early modernism. And the garden tradition continued with Cornelia, who became a renowned landscape architect in Canada and around the world. She even designed the roof garden of the Canadian Embassy at Potsdamer Platz, which is particularly significant.

Charlotte Hahn's memory

[Translation of transcription]

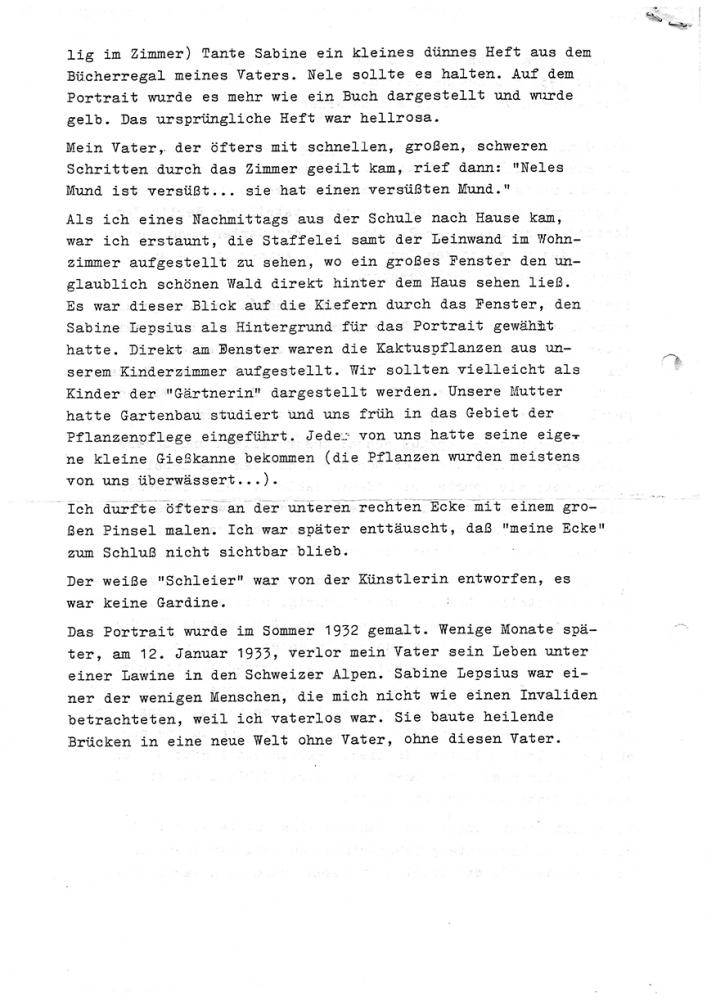

Double Portrait of Cornelia and Charlotte Hahn, painted in 1932 by Sabine Lepsius.

Reminiscence by Charlotte Hahn Arner.

The painting reminds me of that “still”: of still being together with part of my family; of my parents, my father and my mother; and of my sister Cornelia (who went by Nele) in Steinstücken, a neighborhood in Berlin’s Zehlendorf district, at Bernhard Beyer Strasse 3; of the gardens even more than the house, of the “outdoors” with its rock and perennial garden designed by Karl Förster.

The Hahn family had been exclusively painted by Reinhold Lepsius, but he had died back in 1922. And so in 1932, my father asked [Reinhold’s] widow Sabine Lepsius, also a well-known portrait artist, to paint us. To do it, she moved in with us in Steinstücken for several weeks. Originally the picture was supposed to be painted in two weeks, but that stretched out to four.

We already knew Sabine Lepsius; our parents and grandparents, the Jastrow and Hahn families, were close with the Lepsius family; we called her Aunt Sabine. My sister Nele had a “fear” of her – she had a certain gruffness and not much patience; but that was connected to her artistic talent and temperament.

A big easel was set up in my father’s study. Nele, 11 years old at the time, was supposed to sit and I, Charlotte, a six-year-old, was supposed to stand. We were given clothes to wear that my father had brought home from a business trip to Romania. I was amazed at how quickly a sketch of both figures appeared on the canvas thanks to a big wide paintbrush. I never had to stand very long for the painting. We got along. I was allowed to go out to the garden now and then. During those breaks, the artist used to feast on various little meals that she was served straight from the kitchen.

Nele, with her “fear” of Aunt Sabine, had to sit quite a lot. I noticed [she was having] difficulties drawing Nele’s hands. To solve the problem (I happened to be in the room) ...

... Aunt Sabine took down a thin little notebook from my father’s bookcase.

Nele was supposed to hold it. On the portrait, it was shown more like a book and it became yellow. The original notebook was light pink.

My father, who often used to rush through room with big, quick, heavy steps, would shout: “Nele’s mouth is sweetened... she has a sweetened mouth.”

One afternoon, when I got home from school, I was surprised to see that the easel including the canvas had been set up in the parlor, where through a small window, you could see the incredibly beautiful forest directly behind the house. Sabine Lepsius had chosen that view through the window of the evergreens as the background for the portrait. The cactus plants from our bedroom had been placed right on the windowsill. Perhaps we were being depicted as the “gardener’s children.” Our mother had studied horticulture and initiated us in caring for plants from a young age. Each of us got her own little watering can (we usually over-watered the plants...).

I was often allowed to paint on the bottom right corner with a big paintbrush. Later, I was disappointed that “my corner” wasn’t visible at the end.

The white “veil” was invented by the artist; there was no curtain there.

The portrait was painted in the summer of 1932. A few months later, on 12 Janaury 1933, my father lost his life in an avalanche in the Swiss Alps. Sabine Lepsius was one of the few people who didn’t view me as an invalid for being fatherless. She built healing bridges into a new world without Father, without that father.

How did Sabine Lepsius end up being commissioned for the portrait?

Bertz: Her husband, Reinhold Lepsius, had previously painted the Hahn family. After his death in 1922, Sabine depended on her private network for support. The Hahn family was part of this network, and they invited the portraitist to spend the summer in Steinstücken and paint the girls.

What significance do Charlotte’s written memories have for your work?

Bertz: Charlotte’s words allow us access to a certain kind of personal memory. It is very rare that we have access to these kinds of personal memories. The perspective of those who are directly connected to the objects is eminently important to us as museum curators. The original historical recording of her voice is a rare windfall.

Inka, there are photos from 1997 of you unpacking the painting. Can you remember that moment?

Bertz: To be honest, I hadn’t thought about it for a long time before I saw the photos again. The photos also show the girls’ distant cousin Hans Herter as well as Hedwig Wingler. It was through Hedwig and Hans that we made contact with Cornelia and Charlotte. When Cornelia visited Berlin in 1998, I had the pleasure of getting to know her and her daughter Wendy.

What can you tell us about the acquisition?

Bertz: Back then I hadn’t been at the museum for that long, and that acquisition was one of my first. The accession number is from 1996, but it took a good half a year from the first contact to the unpacking, which isn’t unusual. Incidentally, we’ve also kept in touch with Hedwig in the time since.

What was it like corresponding with Cornelia during the gifting process for the blouses?

Maier: We communicated through her daughter Wendy. Cornelia, who would have turned 100 in June 2021, passed away in May. She signed the gifting contract for the blouses in February. I was deeply moved by the sight of her precarious signature. Writing by hand was clearly difficult for her at her advanced age but she was thrilled to know that these precious blouses would be well cared for at the Museum, alongside the painting.

Why was it so important for her to gift the blouses to the museum?

Maier: We’d asked Wendy if her mother could say something about the blouses. Wendy answered, “We're happy to know the blouses will be at the Jewish Museum. This is the right place!”

Bertz: A story finding its completion is not only important for us at the museum. It is also necessary for the donors to have closure for themselves in terms of their own life stories. Sometimes there are these moments of serendipity when an object fits right in at the museum, especially when its meaning becomes “denser” in the context of the other objects.

You’ve been in contact with the Hahn family since 1996. What role does cultivating relationships with donors play in your work?

Maier: As a rule, it’s never just a matter of an object changing hands. We reach out to the donors, listen to them, and show interest in the stories associated with the objects. There’s often a whole world behind them. With some donors, such exchanges take place over a period of years. With others, it may be limited to a one-time meeting or a brief correspondence.

Bertz: It’s about trust, and trusting that we’re handling history in an appropriate manner. Behind this is often the need to affirm one’s own biography, to have it acknowledged. For all parties, this is a complex and emotional process that goes beyond simply handing over a historically relevant object. The museum is a storehouse of memories. It’s not just a collection of objects.

The interview was conducted by Immanuel Ayx, September 2021

Citation recommendation:

Immanuel Ayx (2021), “The museum is a storehouse of memories”. Embroidered traditional blouses, ca. 1920–1930, gift of Cornelia Hahn Oberlander, 2021.

URL: www.jmberlin.de/en/node/8187