New Accents

An Interview with Cilly Kugelmann

The JMB’s new core exhibition is entitled Jewish Life in Germany: Past and Present. On 3,500 square meters, the exhibition tour alternates historical narrative with insights into Jewish culture and religion. We talked to Cilly Kugelmann, the exhibition’s chief curator, about new concepts, modern design and the challenge of setting new accents.

Cilly Kugelmann, you are chief curator of the Jewish Museum Berlin’s new core exhibition. The exhibition presented at the JMB up to 2017 was extraordinarily successful. What has changed, and what will make the new show different from the previous one?

Jewish history hasn’t changed, of course—but our new exhibition accents things differently than before. We are also working with modern exhibition design and an exhibition architecture that integrates the Libeskind building closely. Additionally, the exhibition is based on a different model, in that we separate out the portrayal of historical epochs from the presentation of particular themes in Jewish culture. In the theme-based spaces, visitors can explore religious aspects of Judaism in depth and think about art, music, or discover our family collections.

The exhibition tells the story of Jews in the German-speaking area from the Middle Ages up to the present day. Given such a long span of time, is it even possible to name a single core emphasis of the exhibition?

Yes! What we now stress is the interaction of Jews with their Christian, or non-Jewish, environment. In every era, the various forms of Judaism have taken shape out of that interaction. There are indications of this in what was adopted from Christian neighbors and what theological elements evolved out of a conscious process of demarcation. If I had to pick one focal point out of our multilayered exhibition, it would be that continual interrelationship. Of course, the perspective we take is always a Jewish one. Within this framework, three points have to be carefully borne in mind—just as in any exhibition: the topic has to be relevant; it has to be capable of three-dimensional representation, that is, representation through objects; and it should integrate the museum’s own collections. But for the period from antiquity, especially, and up to the mid-nineteenth century, there are actually very few objects. To compensate for that, we make a lot of use of audiovisual material such as video presentations, models involving projection, and graphics.

X

X

Cilly Kugelmann was Program Director of the Jewish Museum Berlin from 2002 to 2017. She published several books on post-war history and antisemitism and is the chief curator of the JMB’s new core exhibition; Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Yves Sucksdorff

More than 500 objects from our collections wait to be discovered in our Family Album; Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Yves Sucksdorff

Could you give us an idea of what visitors can expect to see in the rooms on Jewish history?

The historical part of the exhibition begins in the early Middle Ages. It is not entirely clear when the first Jewish communities settled in northern central Europe, a region that has come to be known as “Ashkenaz”. In the exhibition, we address that question in a fictional dispute between a Jew and a Christian: Who was here first? What we do know is that in some medieval towns, Jews and Christians lived together in close proximity. An interesting source for that is the "Sefer Hasidim", the "Book of the Pious". This is a kind of handbook written by a group of pious Jews with instructions on everyday life in medieval Germany. The book gives very practical guidelines as to how Jews should behave towards Christians—for example, when a Christian may be asked for help, or how to conduct oneself near a church to avoid anybody thinking it is a holy place for Jews.

What is Ashkenaz?

Ashkenaz, Hebrew, used since the Middle Ages to describe the area of present-day Germany, later also a description of (northern) France and northern Italy.

At the same time, we also find hostility and violence against Jews in the Middle Ages. This was expressed in, for example, allegations of “host desecration”, whereby Jews were accused of injuring or killing the body of Jesus by stabbing the altar bread. These are very stark images, but they characterized the Christian-Jewish relationship as well. So we show both aspects: neighborly coexistence, and the confrontation with persecution and murder.

You once described these early persecutions as the “germ” of antisemitism.

That’s right—or more precisely, they are the beginning of anti-Judaism. Christianity saw itself as having succeeded Judaism in the covenant with God. That becomes evident in the Christian terms “Old Testament” and “New Testament”. The Christian Church staked a new claim to power—and that power had to be reaffirmed towards the Jews again and again. In the exhibition, we show the two allegorical figures Synagoga and Ecclesia: Ecclesia stands for the triumphant Church, while Synagoga is her antithesis, disempowered and humiliated Judaism. But we also show, through the example of medieval book illustrations, how Jews dealt with the negative Christian image of Judaism and reinterpreted it in a positive way.

X

X

The two medieval allegorical figures Ecclesia and Synagoga stood for the triumphant Church and the disempowered and humiliated Judaism; Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Roman März

The Middle Ages ended with expulsions, persecutions, and murder. Most of the Ashkenazi Jews fled to northern Italy and eastern Europe. Why did Jews come back to settle in Ashkenaz in the early modern period?

Between the Middle Ages and the early modern period, acts of violence took place that, in the context of their era, come close to the Holocaust in their destructive impact. Later on, Jews gradually began to resettle the region, mainly in rural parts of Ashkenaz and mainly for financial reasons: for the rulers of these territories, Jews were a lucrative business opportunity because they had to pay special taxes and levies. We have now reached the period of absolutism, when the German lands were made up of many small states under absolutist rulers who could issue whatever laws they liked.

The territorial lords waged expensive wars and maintained elegant courts. A small group of talented Jewish merchants became “court factors”, whose job was to arrange the supply of luxury goods and military funding for the court. These court factors belonged to Jewish communities, and they generally used their influence for the benefit of their community. We present this situation using several examples—including the case of a woman, the celebrated Madame Karoline Kaulla. She was a gifted entrepren€ who became famous as an advocate for her community in the southern German town of Hechingen.

View of the exhibition room Early Modern Times with the Portrait of Johann Georg Faber, mayor of Lichtenfels, Sebastian Mahlmeister, a hunter, and Samuel Salomon, a court Jew in Reichmannsdorf; Johann Georg Faber, Reichmannsdorf, ca. 1730, Oil on canvas; Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Yves Sucksdorff

From the mid-fifteenth century on, Johannes Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press changed the world; it also created a whole new profession. The dissemination of Hebrew and Yiddish writings expanded. The case of an itinerant printer shows what the new textual formats looked like and where the new readerships were located. Most Jews, though, earned their living in the countryside on the basis of regional trade.

For Europe, the early modern era ended with the French Revolution, which appears in the exhibition in the slogan Egalité.

The term Egalité introduces the next historical segment, the era of Enlightenment. It begins with emancipation—that is, a detachment from the sacred core of Judaism and a movement into secular society. In France, Jews acquired legal equality with all other citizens after the Revolution. In Germany, that process took another century. In the more than three hundred German territories, emancipatory legislation might be passed but then reversed, or never instituted in the first place. It was only with German unification in 1871 that Jews gained equal citizenship.

Many times throughout that long period, legal equality was made contingent on the Jews fulfilling some particular requirement: first they had to prove they were capable of citizenship; first they had to learn to conform to the dominant culture, and so on. That’s the German principle, before rights will be granted. You can see present-day parallels in the debate about the integration of refugees. So the theme of this epoch is: How did society open up to grant Jews equal rights, and how did Jews process that internally? What conflicts did they experience, what new opportunities did they welcome, what disadvantages did they fear? In this period, it became possible for the first time to build magnificent and highly visible synagogues. At the same time, the liturgy of the service was adapted to a Christian model, including new musical compositions. A virtual reality installation will enable visitors to take a stroll in one of these sacred buildings, which no longer exist in bricks and mortar.

For many Jews, the First World War confirmed their integration into German society. A large collection of accolades and honors, in the form of medals handed down within families, documents their pride in having taken part in the war for the Fatherland as German Jews. This was an epoch of acculturation—of adaptation to the surrounding German culture. That forms the nexus of all the various themes we bring together in this part of the exhibition.

The segment ends with a film installation on the Weimar period. What does it show?

The Weimar Republic’s fifteen eventful years are portrayed in three chapters. There’s the integration of Jews into German society, which was regarded as successful at the time, and in parallel the emergence of a new Jewish self-confidence, the “Jewish Renaissance”. And then there’s the new type of political antisemitism that cast its shadow over the Weimar years.

X

X

Soldier’s portraits. Jews enthusiastically stood up for the fatherland as soldiers—the participation was considered a milestone of emancipation; Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Roman März

So in the exhibition, what you call the epoch of emancipation lasts from the end of the seventeenth century right up to 1933. Why is that?

Not all historians will agree with our categorization. But in the exhibition, we see this long stretch of time less as a historical periodization than as a picture of an epoch, representing the time between two poles: from the beginning of the Jews’ struggle for legal equality to the abolition of all their rights under Nazism, a process that began when the Nazis took power in 1933.

How do you portray the Nazi period?

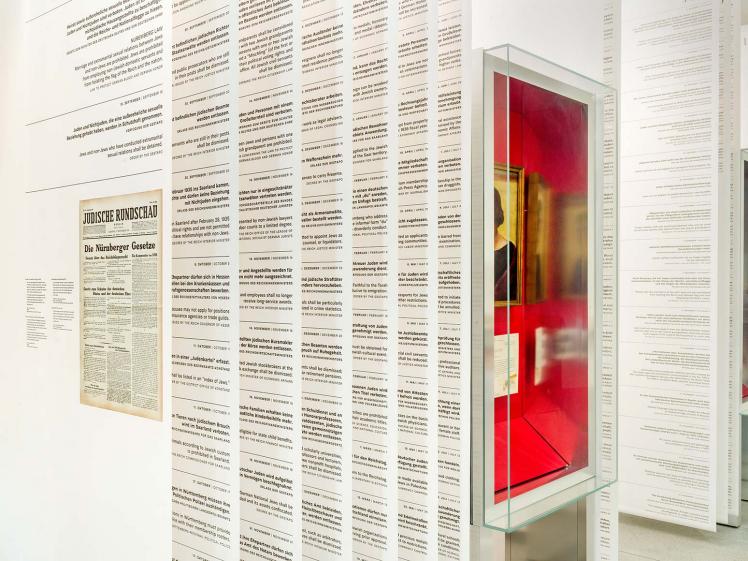

In the room titled "Catastrophe," there is a powerful installation: 962 anti-Jewish laws and policies form the backdrop for the display. What was new about the antisemitism of the Nazis was that it became government policy. That meant the Jews were now completely at the mercy of the state. Alongside this “legal” dimension, there were countless attacks on Jews in the shape of physical violence, which we show on a large map of the German Reich.

Representing Nazism poses a special challenge, and not only in a Jewish museum. We have to take account of the feelings of aged people who experienced the Holocaust, and of their descendants. In recent decades, exhibitions and publications about the Nazi era have tried to turn the spotlight onto individual destinies, individual life stories. “Giving Faces to the Numbers” or “From Neighbors to Jews” were the kinds of titles chosen. But important as individual life stories surely are, we also place value on showing the political developments in those years. As a result, our exhibition addresses both the structure of the Nazi state and individual biographical studies of Jewish families, revealing how the devastating conditions of the Nazi years impacted on their lives.

The installation of 962 anti-Jewish laws and policies form the background of the exhibition room Catastrophe; Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Roman März

In contrast to the previous permanent exhibition, we have now arranged the Nazi period in three broad chapters. The first runs from 1933 until the violence of Kristallnacht on 9 November 1938. These were years when many Jews still wondered whether they could stay in Germany or should plan for a future abroad. The period from November 1938 to 1941 includes the outbreak of war, whenthe growing harshness of anti-Jewish measures escalated to unbearable proportions and attempts to leave Germany became a desperate gamble. The beginning of the war against the Soviet Union marks the start of the third chapter. From 1941, what we now call the Holocaust began to take shape: the systematic murder of all Jews wherever the Nazis took control.

You said at the beginning that the exhibition focuses on the relationship between Jews and non-Jews. But is the term “ relationship” really justified in the context of the Holocaust or in the immediate postwar period?

Most certainly, even if it was a very one-sided relationship, enforced by the Nazis, in which no meaningful options ultimately remained open to the Jews.

The period after 1945 takes up more space in the new exhibition than it did in the old one. We trace an arc from the end of the war up to the most recent wave of immigration of Russian-speaking Jews. Our view onto postwar history begins with photographs and testimonies of survivors of the mass destruction.

We exemplify the topics of restitution and reparations through two very different cases. An important emphasis is placed on the relationship between Germany, Israel, and the Jews in Germany, a striking triangle in the project of “working through the past”—that is, debates around Germany’s political responsibility for the Holocaust. What role does Israel play in that?

In postwar German history, culpability and responsibility for the crimes of Nazism were negotiated mainly within the bilateral relationship between Israel and Germany, and not with the Jews who still lived in Germany after the end of the war. The very fact that the State of Israel was founded changed the self-image of Jews all over the world forever. Thanks to Israel, Jews and Judaism now have a physical, religious, and cultural center. The postwar triangle of Israel, Germany, and Jews living in Germany was both fascinating and extremely precarious, something that we can’t show in all its breadth and depth. Instead, we pick out particular important events to stand for the whole. An example is the 1976 hijacking that ended in Entebbe, in which the German radical Red Army Fraction played a part. The links between Palestinian and German terrorism of the 1970s left traces that are still visible today, in the fact that Jewish institutions are protected by security guards. I think our presentation will prompt controversial discussions—something that is both important and to be expected for every exhibition and every publication.

The section on antisemitism in the exhibition begins with a quote from Theodor W. Adorno: “Antisemitism is the rumor about the Jews.” How do you approach this theme?

It was important to us to have a module that doesn’t show antisemitism from a simplistic perspective. We would like to convey to visitors how difficult the topic of antisemitism is to deal with. You can’t simply look at pictures and say: “Yes, that’s antisemitic.” In a film-based media station, we use four examples to discuss the question of what actually constitutes antisemitism. They don’t address only incontrovertible forms of antisemitism, but also events that invite arguments about whether or not they are antisemitic. Our aim is to dig a little more deeply into the matter, and to show our audience that it’s possible to go beyond hasty judgments.

We have talked a lot about the structure of epochs in the exhibition, but there will also be thematic spaces on cultural and religious aspects of Jewish life.

Yes, these thematic rooms have an important function. Theoretically, we could have classified each historical epoch under the relevant aspect of religious life, and shown historical changes through that prism, but it would be very difficult for a range of reasons—not least because you need to know a lot about a theme before you can understand historically conditioned changes within it. In the dedicated thematic spaces, we can pay more profound and detailed attention to Jewish themes such as the Holy Scriptures and their significance in the everyday life of a particular period.

The Torah is the main exhibit in the center of the first room in the exhibition; Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Roman März

In our exhibition, visitors can gain a clear idea of what being Jewish means in everyday life, what is meant by Shabbat, or how different differently people deal with religious laws and prohibitions. We have also devoted a thematic room to ceremonial objects. We display them very visibly in all their splendor, in a spectacular case presented according to their importance in terms of their holiness. Theme-based rooms offer a great opportunity to present beautiful objects within a very special exhibition design. They promise to be impressive spaces!

Do you see something that has characterized Judaism and Jewish life over the millennia? Is there something that has always remained unchanged?

For me, what has remained unchanged is a capacity: the Jews’ capacity to be flexible, to find their way in constantly new situations, navigating between tradition and transformation. Of course, the traditional aspect lies in the laws (and there are many people who don’t keep those). But there’s something else—and no term is really suitable: in the Weimar Republic, it was called “the tribe”. In antiquity, too, Judaism was described as a tribal religion—unlike Christianity, which entered the world as a universal religion with Christ’s birth. Judaism has a component of universality and a component of particularity at once. Stances on those two aspects of Judaism have changed again and again over history, from feeling affiliated to a group that built a kind of wall about itself, right up to a group in today’s modern society, where people still sense a form of belonging, but often can’t explain quite why.

Is there a particular insight that you hope visitors will gain from the exhibition?

I think the most important insight is always a little obvious: cultures do not arise out of themselves alone. Cultural, religious, or secular characteristics always evolve in an active confrontation with others—for example, with the majority culture. There is friction between people, between what different people do or say. And Jewish life as we know it today has emerged out of that tension. Through a range of historical examples and presentations, our visitors will discover this relationship of tension and gain an impression of how German-Jewish life and the history of the Jews in Germany took shape.

Thank youfor the interview!

The interview was conducted by Marie Naumann & Katharina Wulffius

This interview was first published in 2020 in issue 21 of the print edition of the JMB Journal.

X

X

View of the exhibition room Hall of Fame. Illustrations: Andree Volkmann; Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Yves Sucksdorff

Citation recommendation:

Marie Naumann, Katharina Wulffius (2020), New Accents. An Interview with Cilly Kugelmann.

URL: www.jmberlin.de/en/node/7397

X

X