Our Museum’s History, Part Two

Controversies and Contradictions

The concepts agreed upon in the 1980s contained many ambiguities and textual compromises as to whether the Jewish Museum would have organizational independence within the Berlin Museum and how exactly the "integrative concept” would be concretely implemented. Daniel Libeskind’s architecture added another new interpretation.

Throughout the 1990s, conflict among the various stakeholders continued to escalate. Several factors played a role:

- The architectural design’s reception

- The question of how to implement the design and allocate the rooms of the Libeskind building

- The merger of the Berlin Museum with eastern Berlin’s Märkisches Museum to form a City Museum Foundation

Daniel Libeskind’s Design:

Extension to the Berlin Museum or a Jewish Museum?

The Berlin Senate intended to implement Daniel Libeskind’s design and, at the same time, retain the "integrative concept,” which conceived of the Jewish Museum as part of the Berlin Museum.

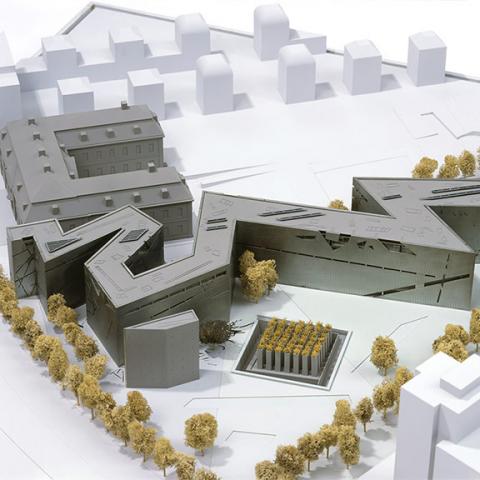

Most of the architectural designs submitted to the 1988–89 competition subdivided the floor area, devoting about a third to the future Jewish Museum as stipulated. Daniel Libeskind’s concept, on the other hand, set out to inscribe symbolically the trauma caused by the Nazis’ crimes into the presentation of Berlin city history.

Inspired by Walter Benjamin’s essay “One-Way Street," a Federal Archives book of remembrance for the victims of the Holocaust, the invisible web of relationships between Jews and Germans, and the unfinished last act of Arnold Schoenberg’s opera Moses and Aaron, he created the "Voids" – cavities that lend the museum a unique atmosphere. Based on the misconception of the Holocaust as "Jewish history," Libeskind’s design came to be seen as a symbol for a "Jewish" museum.

X

X

Brochure from the celebration for the topping-out of the Jewish Museum Berlin, 1995; Jewish Museum Berlin

Numerous publications in the early 1990s were already referring to the design by the shortened form of a "Jewish Museum." In the context of the debate on the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, the building was increasingly perceived as a Holocaust memorial.

Helmuth F. Braun, former Head of Temporary Exhibitions until 2015, on the architecture of the Libeskind Building and its impact on the emergence of the Jewish Museum Berlin, in German

Questions of Authority

In the early 1990s, in the wake of reunification, the Berlin Senate merged the museums of the city’s history. In June 1995, the Stiftung Stadtmuseum Berlin (Berlin City Museum Foundation) was formed from the Berlin Museum of West Berlin, the Märkisches Museum of East Berlin, and other institutions from both sides of the city. The Senate spokesperson responsible for museums, Reiner Güntzer, was named director general of the City Museum Foundation.

By uniting the local history collections in the Berlin City Museum Foundation in 1995, the weight of the Jewish Museum shifted in relation to other areas of the collection. The Jewish Museum was now one of five “departments,” comprising two of the twenty-three "sections" of this museum association. This development jeopardized the original "integrative concept" of Jewish and Berlin history, and minority and majority perspectives, coexisting on an equal basis. The exhibition and storage rooms of the extension were to contain not only holdings of the Berlin Museum, but also the far more substantial collections of the Märkisches Museum.

Shortly before the museum merger, the Israeli art historian and curator Amnon Barzel was appointed head of the "Jewish Museum Department" in the summer of 1994. In 1995, he explained his interpretation of the "integrative concept." He argued that the Jewish Museum should tell the story of the majority society from the perspective of the Jewish minority and not vice versa, as previously planned.

In doing so, he raised the idea of seriously considering the building to be a Jewish Museum – an interpretation already familiar to the public. This forced a reconsideration of the museum’s use, the exhibition concept, and the museum’s administrative status. However, a public discussion of Barzel’s criticism of the "integrative concept" was not what the cultural administration intended.

Reiner Güntzer and the Berlin cultural administration held firm in their conviction to house the Jewish collection only in the basement of the new building, while reserving the rooms on the upper floors for the fashion and theater departments and the city-history exhibition. The latter would also contain a "Jews in Society" section, whose precise content could not be agreed upon.

However, Amnon Barzel, now with the backing of the Jewish Community of Berlin, was pressing for the Jewish Museum to be autonomous not only in cultural matters, but also financially and administratively.

The conflict came to a head in summer 1997, and Amnon Barzel was fired. This attracted international attention, as well as harsh criticism from the Jewish Community.

Inka Bertz, our Head of Collections, on the structure and concept of the Jewish Museum Berlin’s collections before the museum existed and the paradox that the idea of an integrated Jewish museum reduced Jewish history to religious history (in German).

Incompatible Collection Concepts

In November 1992, the Märkisches Museum presented a selection of its exhibits on Jewish history in the Jewish Museum’s rooms at the Martin-Gropius-Bau. These were seen to supplement the holdings of the Jewish Department at the Berlin Museum.

Founded in 1874 as the "Märkisches Provinzial Museum," the collection included not only purchases and donations from Jewish citizens from the period before 1933, but also acquisitions made during the Nazi era and under force. Among them, for example, was so-called "Jewish silver."

The remains of this collection and the circumstances of its acquisition were presented in the exhibition The Other Half in 1992. When Nazi pillaging in 1939 forced Jews to hand over their silver items to the municipal pawnshops, the then director of the Märkisches Museum, Walter Stengel, was able to acquire objects for the commodity price of the metal, which fell far short of the objects’ true value.

The planned merger of the collections of the Berlin Museum and the Märkisches Museum now put the Jewish Department in the precarious position of being assigned to a museum that had been involved in Nazi art looting and whose holdings included Jewish cultural artifacts that had been gained by dispossession.

By contrast, the Jewish Department had often received loans and donations on the explicit grounds that the Berlin Museum had only been founded after the Second World War. The merger with the Märkisches Museum called into question the collection’s ethics and the legitimacy of collecting practices.

Continue to the next chapter of the museum’s history, “Political Decisions.”

Citation recommendation:

Jewish Museum Berlin (2020), Our Museum’s History, Part Two. Controversies and Contradictions.

URL: www.jmberlin.de/en/node/2011

History of the Museum: Ideas, Debates, Decisions, Inauguration (4)