Kurt

Hunting for Clues

The 1,500 family collections and bequests stored at the Archive of the Jewish Museum Berlin are a trove of history and personal stories. They document and shed light on German-Jewish history by showing numerous individuals’ lives.

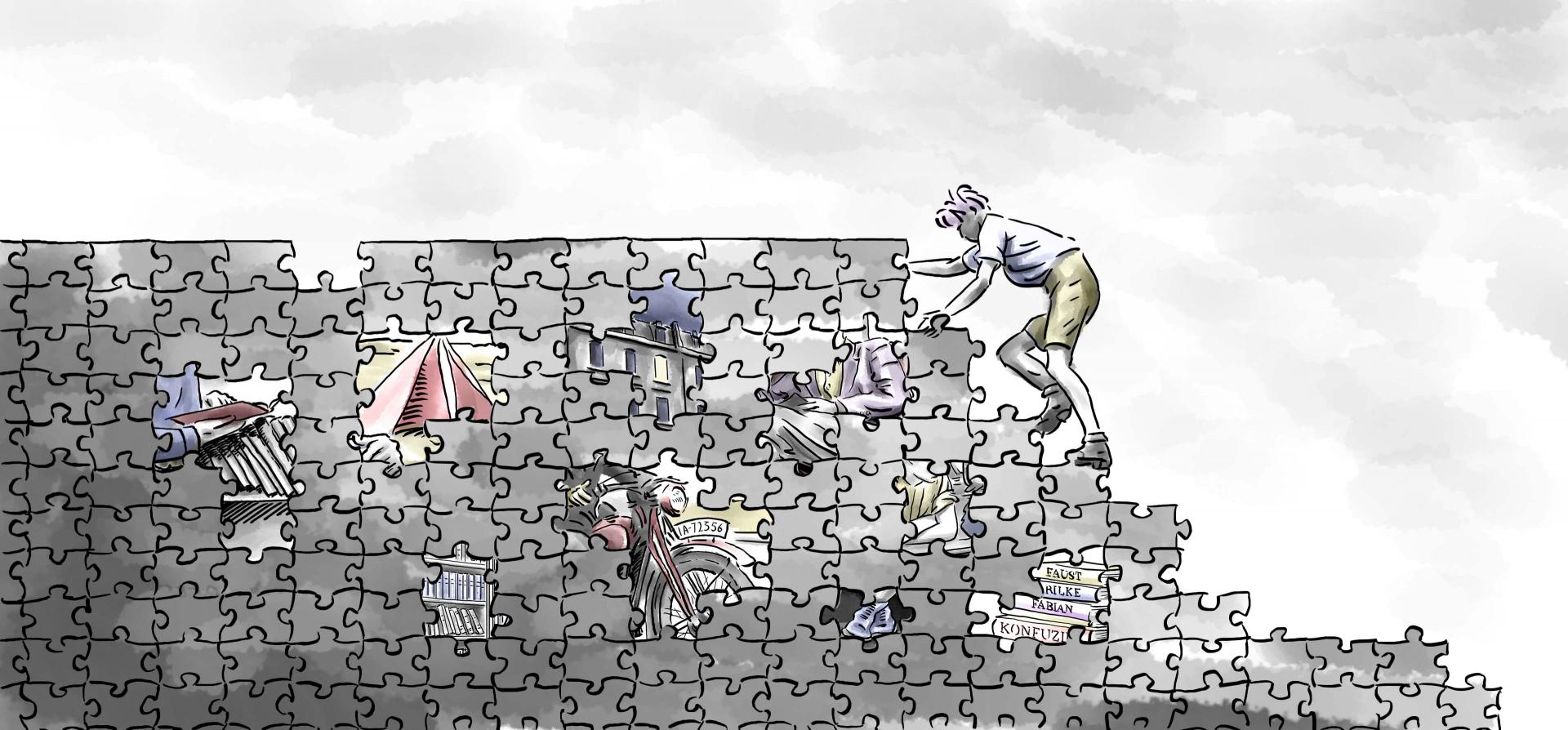

Researchers can view our collections for scholarly analysis in the Reading Room. But before they are made available, new holdings must be cataloged by the staff of the Museum Archive. That inventory process can require background research, which can sometimes become very extensive. With patience, passion, outside assistance, some experience, and a little luck, this process often allows us to fill in gaps and find connections, gradually piecing together a larger picture out of isolated puzzle pieces.

Taking the Oliven Family Collection as an example, we will show what extensive and sometimes surprising insights can emerge from the process of cataloguing and indexing a collection.

Unpacking the Oliven Family Collection; Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Ulrike Neuwirth

Starting Point

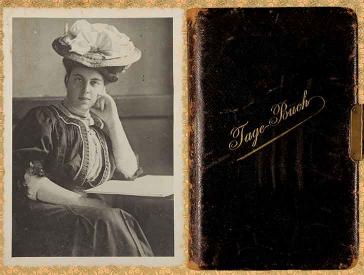

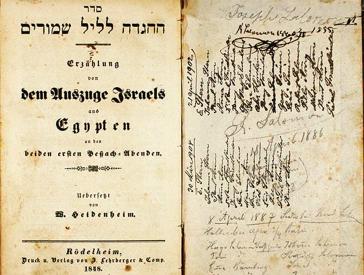

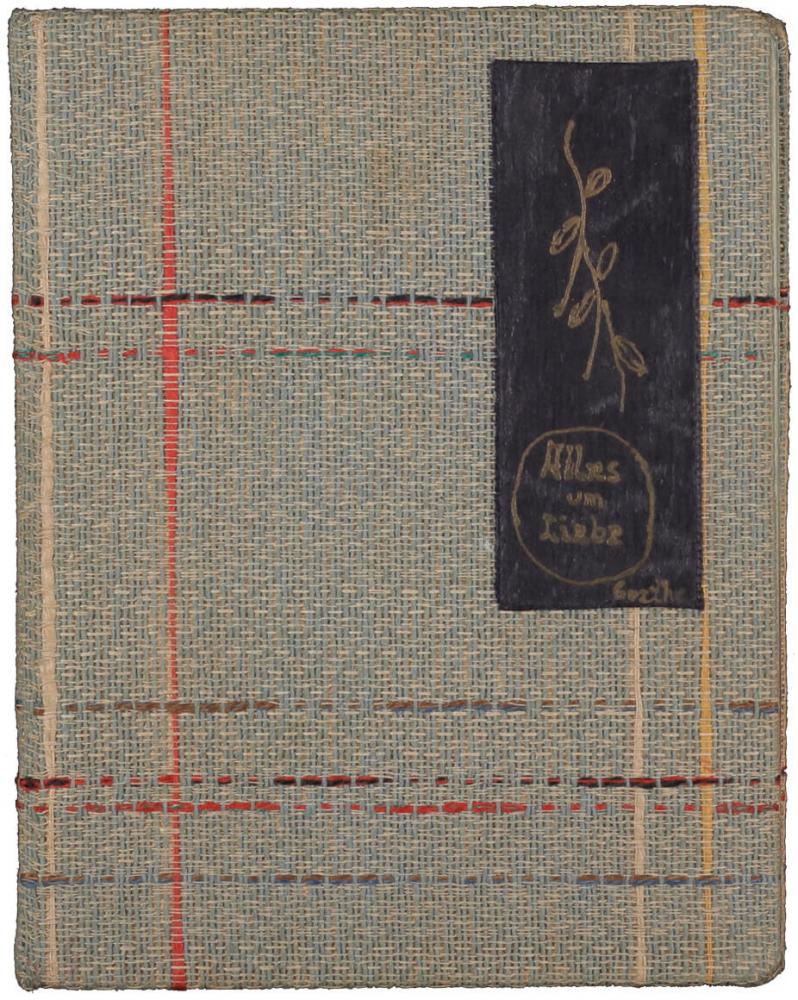

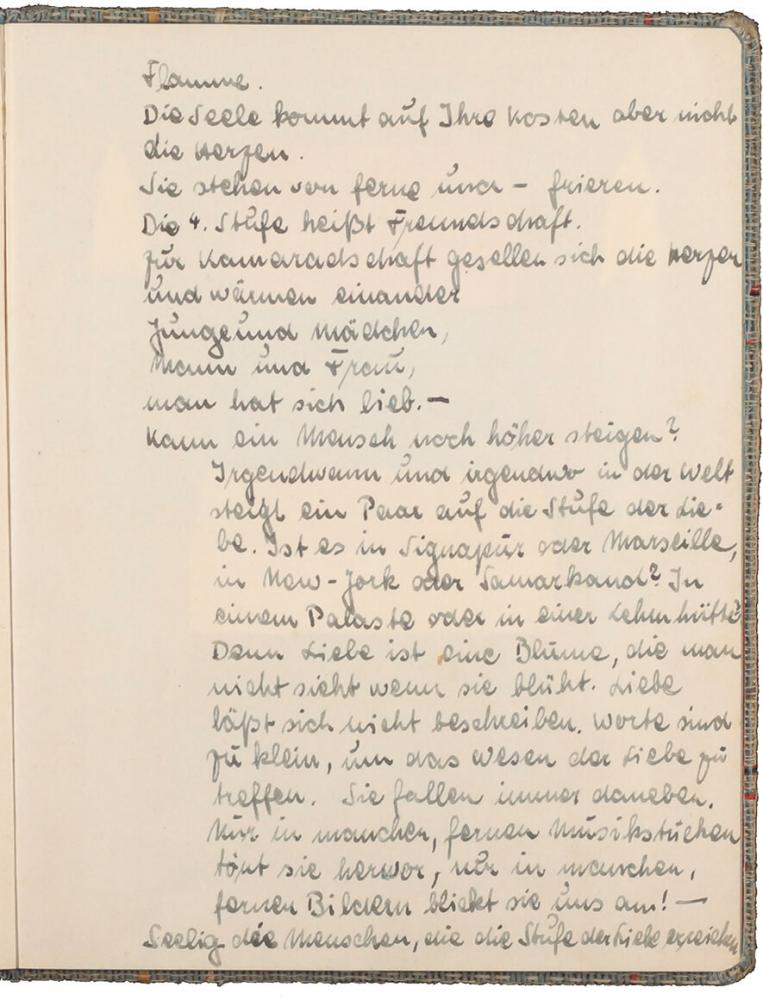

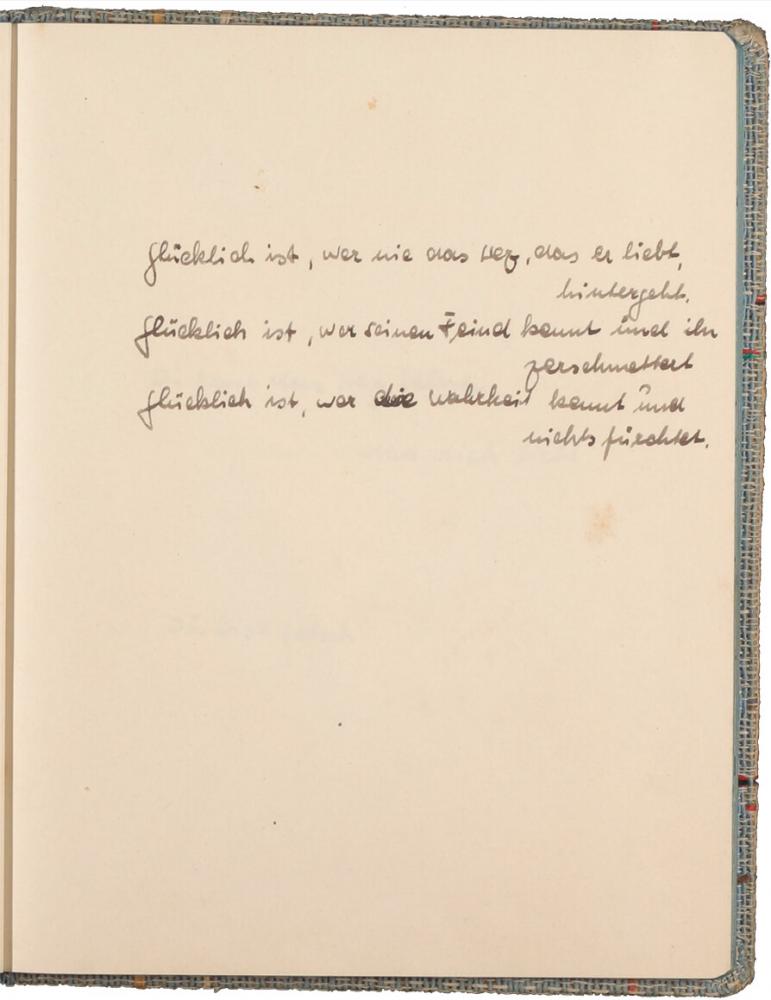

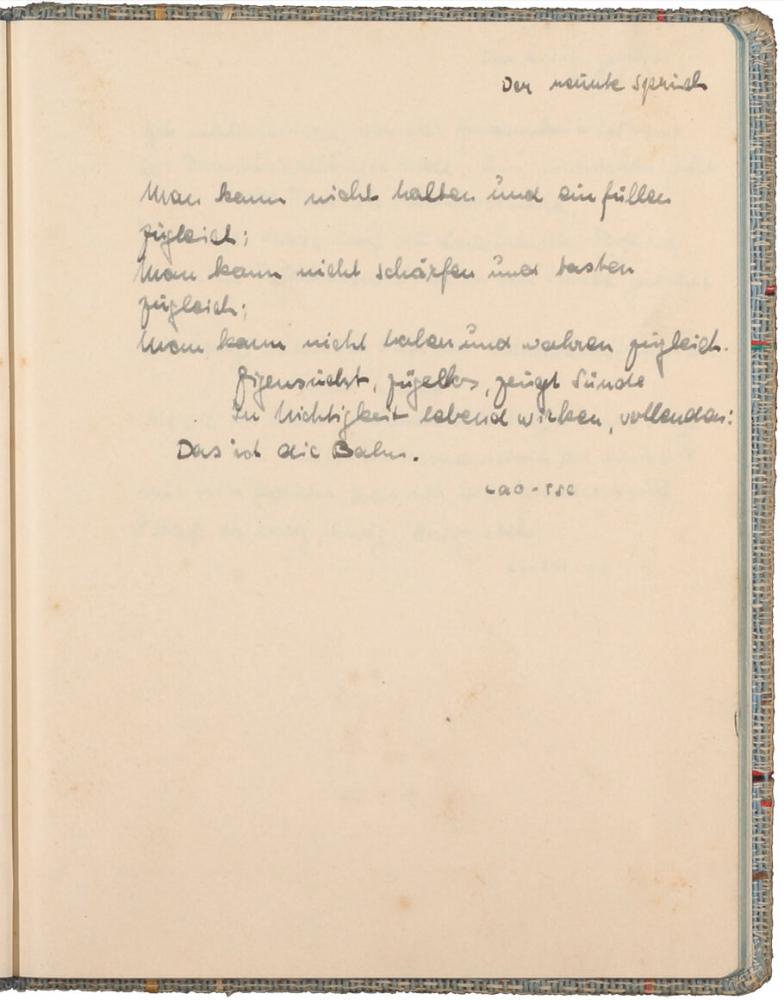

In 2016 and 2018, the Archive of the Jewish Museum Berlin acquired a vast collection from the Oliven Family. After it was unpacked, it wound up on the desk of one of the archive employees to be inventoried. Alongside photographs, diaries, and documents spanning around two hundred years of family history, this collection also included a small book inscribed with the title All for Love, a Goethe quotation, and dedicated “For Klaus from Kurt.”

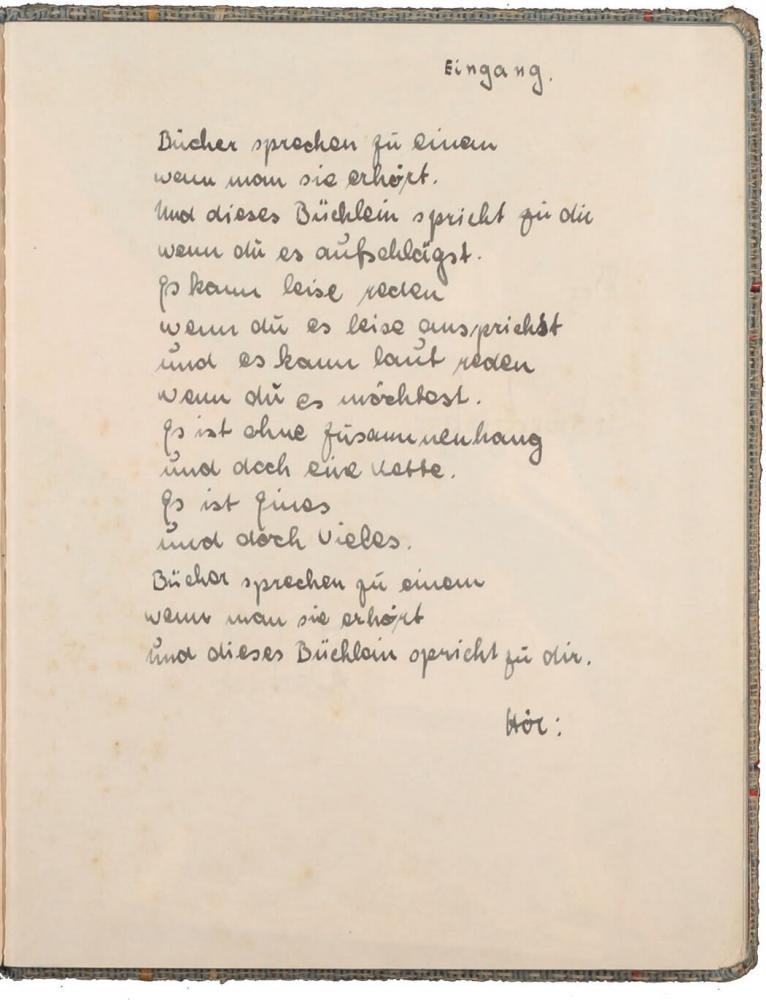

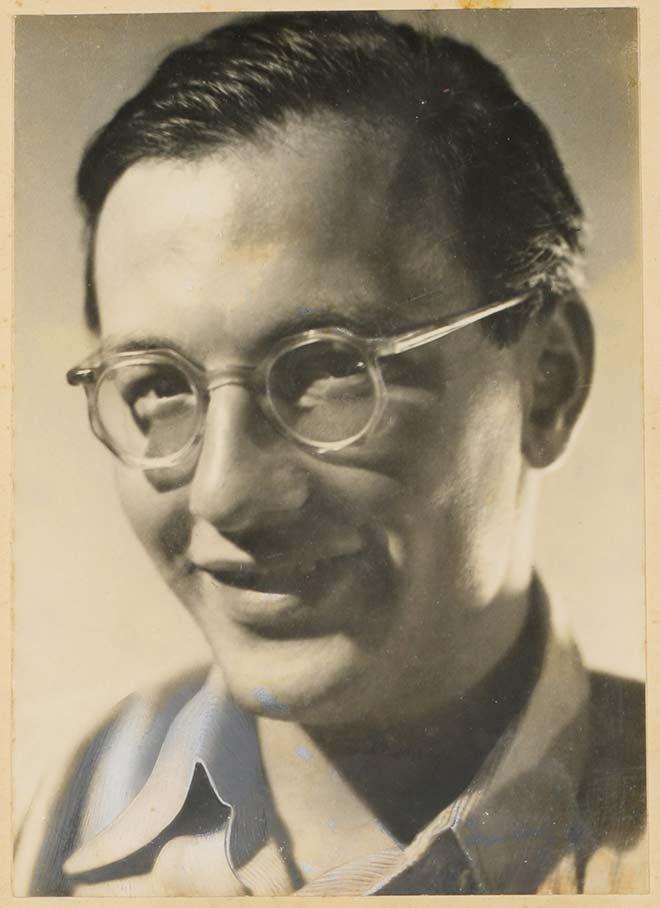

A photograph of Kurt has been pasted in next to the dedication. He is looking straight into the camera with an expression of what might be described as melancholy. The following page reads, in neat handwriting:

“Books speak to a person / if a person hears them out. / And this little book will speak to you / when you open it. / It can talk softly / if you address it softly / and it can talk loudly / if you wish. / It is free of context / yet linked as a chain. / It is one thing / yet many. / Books speak to a person / if a person hears them out / and this little book speaks to you. / Listen:”

The little book contains musings on matters of love, a variety of quotations and poems whose authors we have not always been able to identify, a copy of a “Letter from Silingtal,”

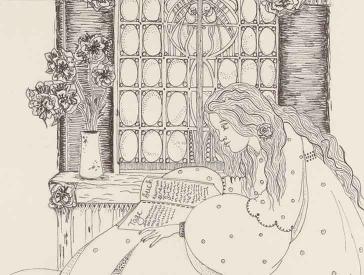

and many lovingly drawn illustrations. See for yourself:

X

X

Portrait of Kurt from the little book All for Love, about 1937 or 1938; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2016/15/322, gift of the Oliven family

All for Love

This and all subsequent images show pages of the little book All for Love, about 1938 (blank pages generally not shown).

Jewish Museum Berlin, gift of the Oliven family

Transkription:

"Prologue

Books speak to a person

if a person hears them out.

And this little book will speak to you

when you open it.

It can talk softly

if you address it softly

and it can talk loudly

if you wish.

It is free of context

yet linked as a chain.

It is one thing

yet many.

Books speak to a person

if a person hears them out

and this little book speaks to you.

Listen:"

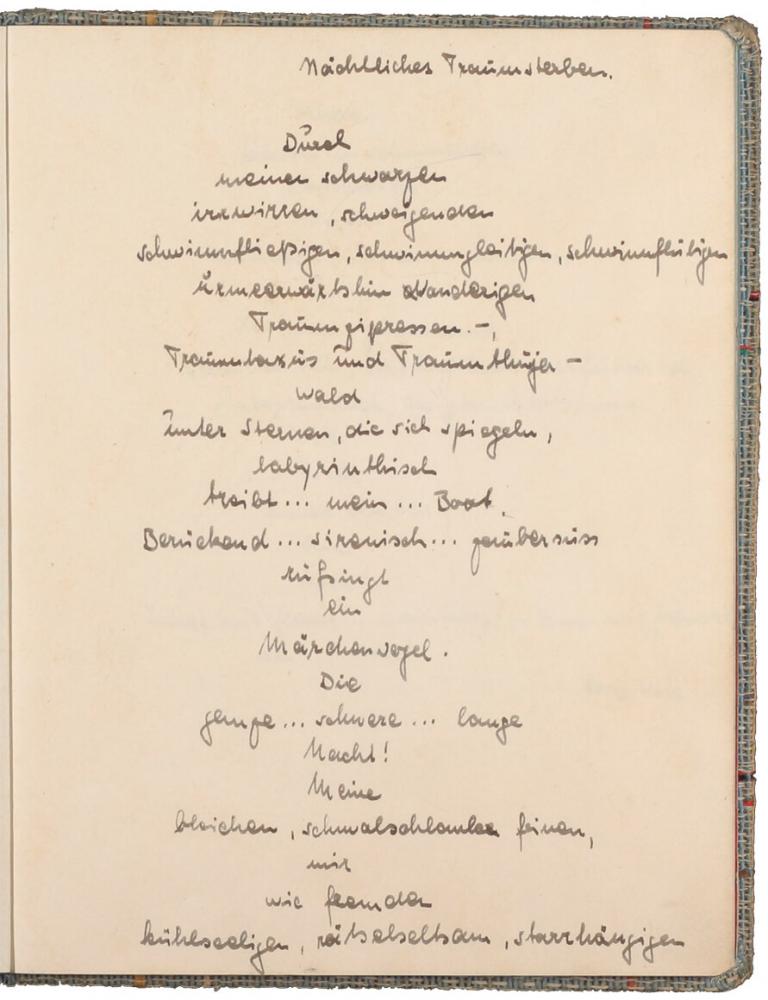

Transkription:

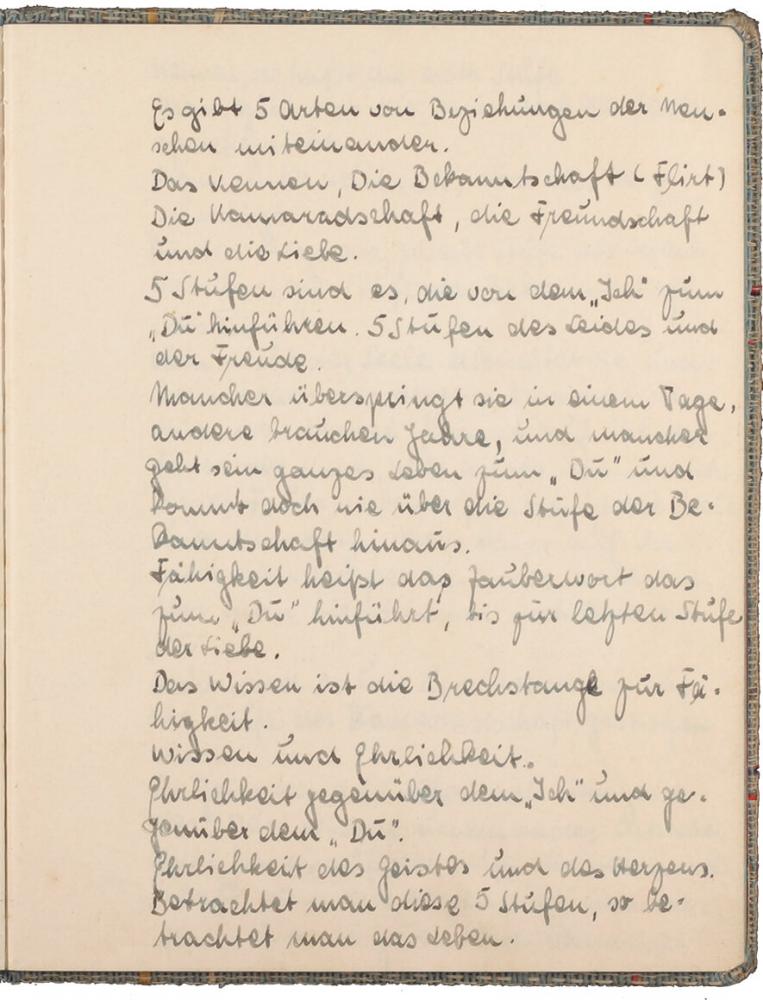

"There are five kinds of human relationships.

Familiarity, acquaintanceship (flirtation),

comradery, friendship, and love.

Five stages that lead from 'me' to the 'you' (du) of intimacy. Five stages of suffering and joy.

Some people leap over them in a day, others need years, and some spend a lifetime on the way to that intimate 'you' but never get beyond the stage of acquaintanceship.

Capability is the magic word that leads to the intimate 'you', to the final stage of love.

Knowledge is the crowbar of ability.

Knowledge and honesty.

Honesty with the 'me' and with the 'you'.

Honesty of mind and of heart.

To observe these five stages is to observe life."

Transkription:

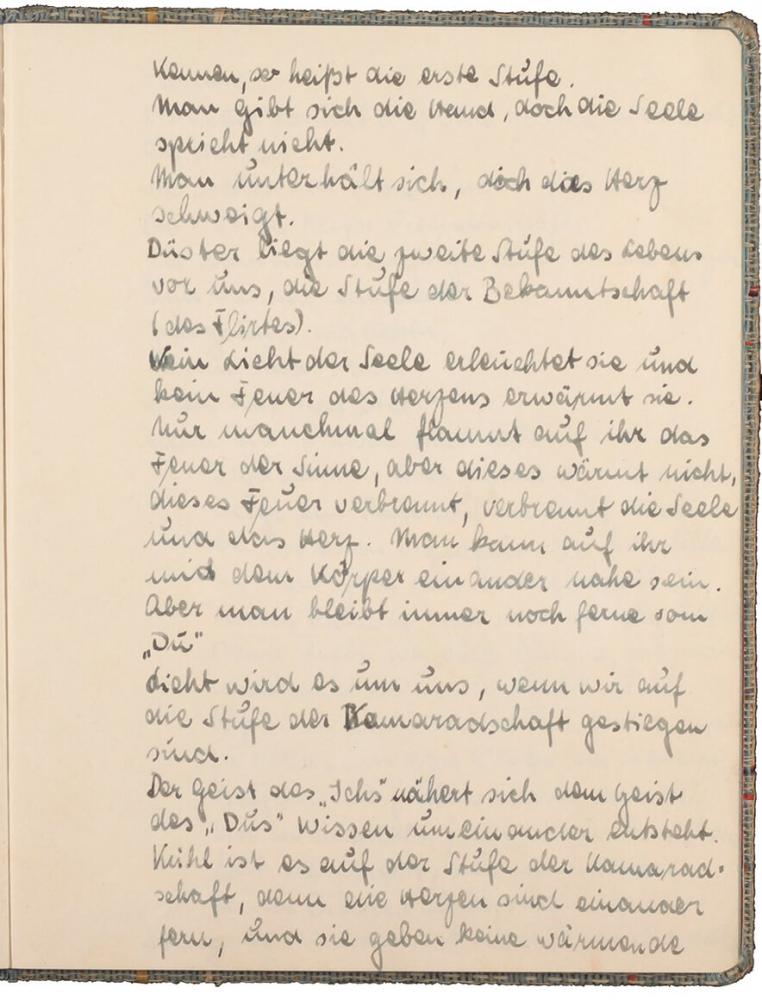

"Familiarity is stage one.

You shake hands, but the soul does not speak.

You have a conversation, but the heart is silent.

Stage two of life lies bleak before us, the stage of acquaintanceship (flirtation).

No soulful light illuminates this stage, no heart-fire warms it. It is only occasionally enflamed by the fire of the senses, but this fire is not warming, it burns out, smolders the soul and the heart. At this stage, you can have physical closeness. But you are still far away from the intimate 'you'.

Light envelops us when we have risen to the stage of comradery.

The mind of the 'me' nears the mind of the 'you' and mutual knowledge emerges. The stage of comradery is chilly because the hearts are far apart and do not give out a warming fire."

Transkription:

"The souls are gratified, but not the hearts.

They wait from afar – and freeze.

Stage four is called friendship.

In comradeship, the hearts mingle

and warm each another

boy and girl,

man and woman,

with affection. –

Can a person rise higher still?

Some time and somewhere in the world, a couple is rising to the stage of love. Is it in Singapore or Marseille, in New York or Samarkand? In a palace or a clay hut? Love is a flower that goes unseen when it blooms. Love is beyond description. Words are too small to strike the essence of love. They always miss the target. Only in some distant music does it resound, only in some distant paintings could we behold it!

Blissful are those who achieve the stage of love."

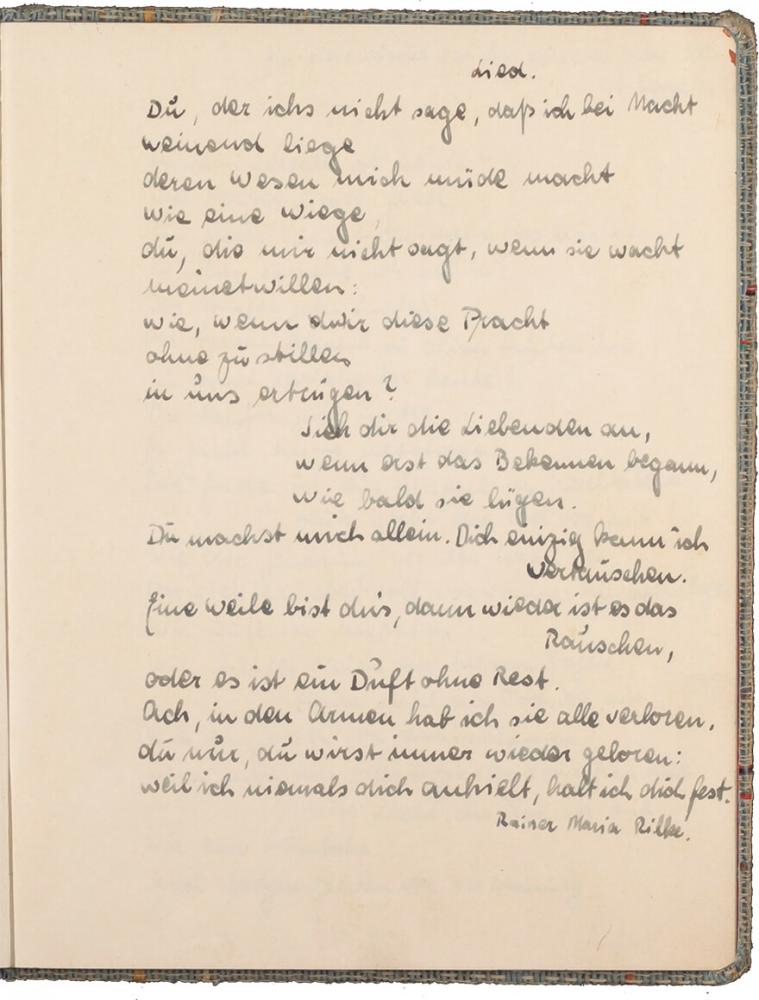

Transkription:

"Song

You, whom I do not tell that all night long

I lie weeping,

whose very being makes me feel wanting

like a cradle.

You, who do not tell me,

that you lie awake thinking of me:

what, if we carried all these longings within us

without ever being overwhelmed by them,

letting them pass?

Look at these lovers, tormented by love,

when first they begin confessing,

how soon they lie!

You make me feel alone. I try imagining:

one moment it is you, then it’s the soaring wind;

a fragrance comes and goes but never lasts.

Oh, within my arms I lost all whom I loved!

Only you remain, always reborn again.

For since I never held you, I hold you fast.

Rainer Maria Rilke"

[translated by Albert Ernest Flemming]

Transkription:

"A Suicide Speaks from the Year 1500 BCE in Egypt

To whom can I speak today?

Hearts are rapacious:

Every man seizes his fellow’s goods.

To whom can I speak today?

The gentle man has perished,

But the violent man has access to everybody.

To whom can I speak today?

The gentle man has perished,

There are no righteous;

The land is left to those who do wrong.

Death is before me today:

Like the recovery of a sick man,

Like going forth into a

Garden after sickness.

Like the odor of myrrh,

Like a cool breeze on a hot day.

Death is before me today:

Like the scent of lotus flowers

When sitting on the banks of intoxication.

Death is before me today:

Like the home that a man longs to see

After years spent as a captive."

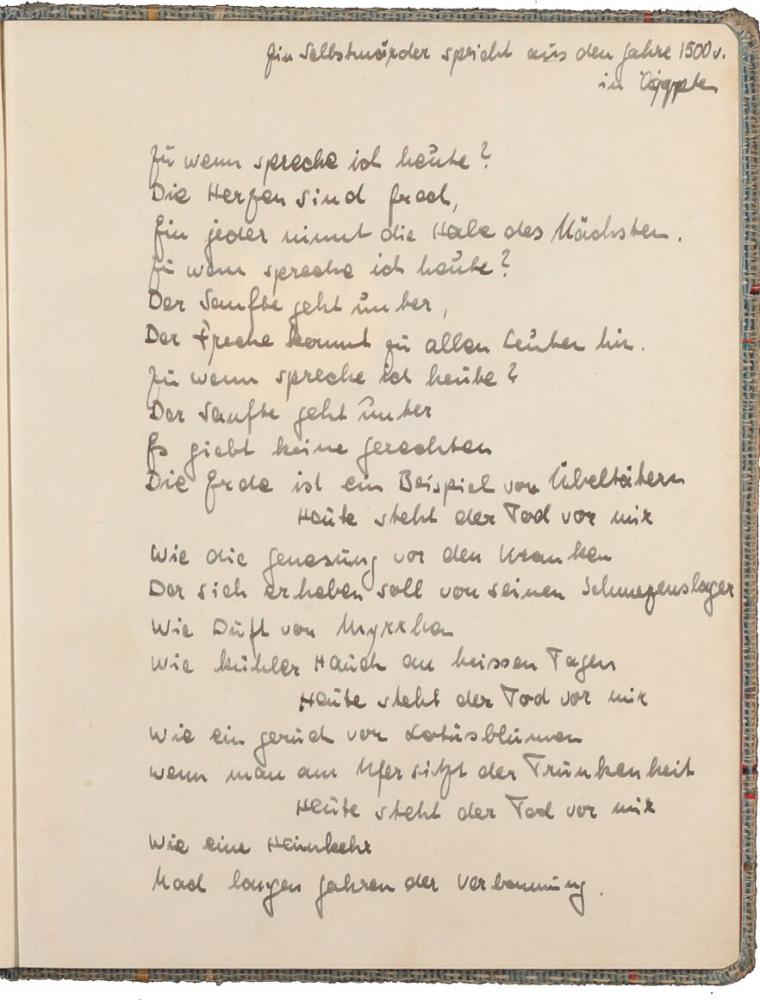

Transkription:

"Nighturnal Dreamdeath

Through

my

madahatter taciturn

floatflowing, floatgliding,

floatflooding black

dreamcypresses,

wanderizing ancient-oceanwards

dreamtaurus and dreamthujer-

forest

under interreflected stars

labyrinthinely

drifts … my … boat.

Beguiling … sirenical … dyssweetifying

a fairybird

callsings.

All through-

out

the … long… thick

night!

My hands,

pallid slimthin fine

as if outlandish

coldsouled, enigmamatic, hangingstiff,"

Transkription:

"Hands

dip down

into shimmering

water lettuce.

Below,

lurking… below… soundless,

below

threatening, glimmering

temptational, emblazonal, seductional

unfathomable, deepdeadsilent

the

… depths! …

on and on

the

banks!

Ever farther from me … my life! … Ever

stranger to me… song!

Arno Holz"

Transkription:

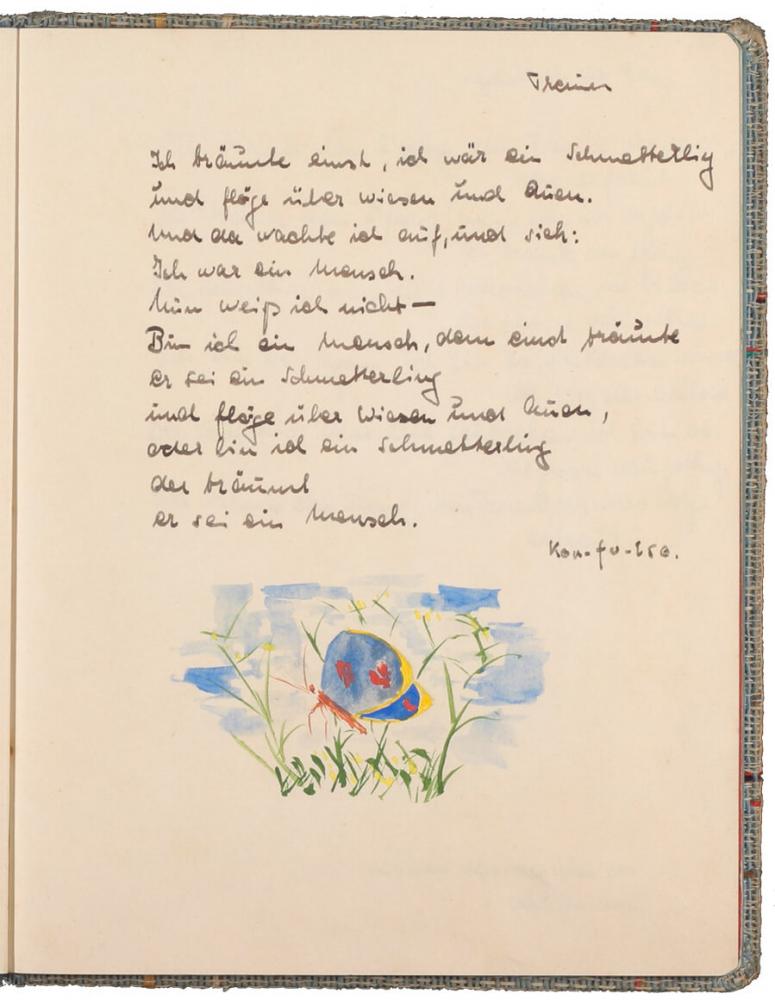

"Dream

Once upon a time, I, Chuang Chou, dreamt I was a butterfly, fluttering hither and thither, a veritable butterfly, enjoying itself to the full of its bent, and not knowing it was Chuang Chou. Suddenly I awoke, and came to myself, the veritable Chuang Chou. Now I do not know whether it was then I dreamt I was a butterfly, or whether I am now a butterfly dreaming I am a man.

Confucius"

[Zhuangzi/Zhuang Zhou, translated by James Legge]

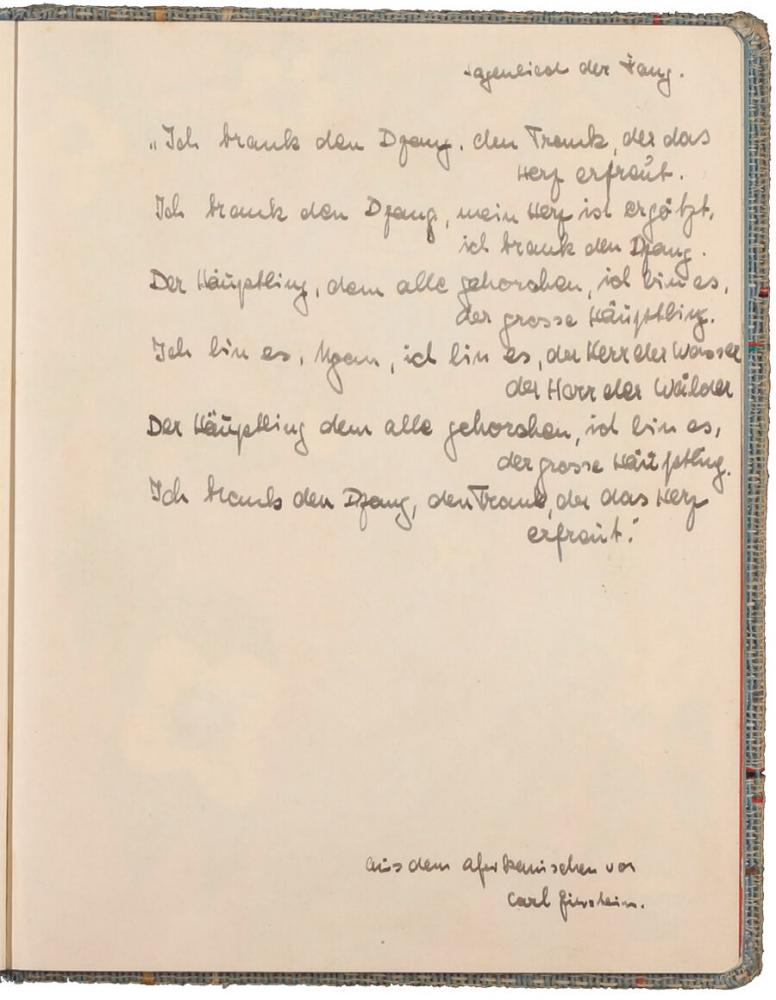

Transkription:

"Chant of the Fang People

'I drank the dzang, the drink that delights the heart.

I drank the dzang, my heart is enthralled, I drank the dzang.

The chief, whom all obey, it is I, the great chief.

It is I, Ngan, it is I, lord of the water, lord of the forest.

The chief, whom all obey, it is I, the great chief.

I drank the dzang, the drink that delights the heart.'

Translated from Fang into German by Carl Einstein."

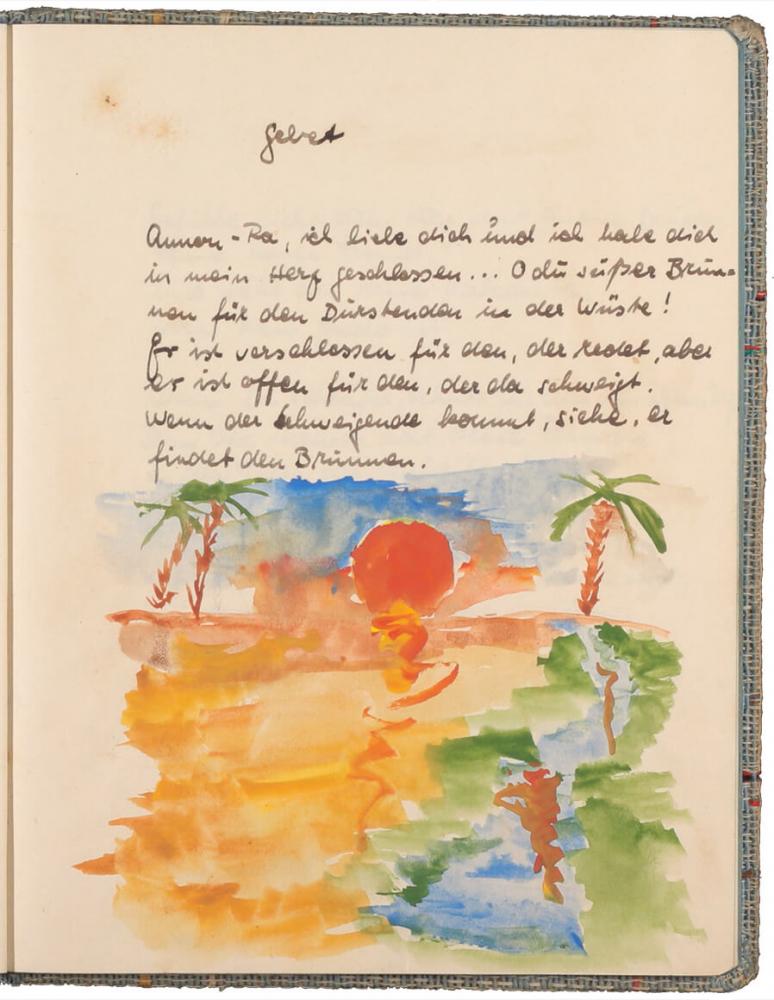

Transkription:

"Prayer

Amon-ra, I love you and have taken you into my heart… O sweet spring for the thirsty in the desert!

He is closed off to those who speak but open to the silent. When the silent man comes, behold, he shall find the spring."

[Egyptian hymn]

Transkription:

"Do not still thy heart with a brother,

know no friend,

and do not select any confidants,

therin lies no end.

When you sleep, keep your heart for yourself

For a man has no friends

In days of doom.

Listen to what I tell you,

That you are a sovereign upon the earth.

That you are a ruler of the land.

That you shall grow strong in goodness.

2900 BCE"

Transkription:

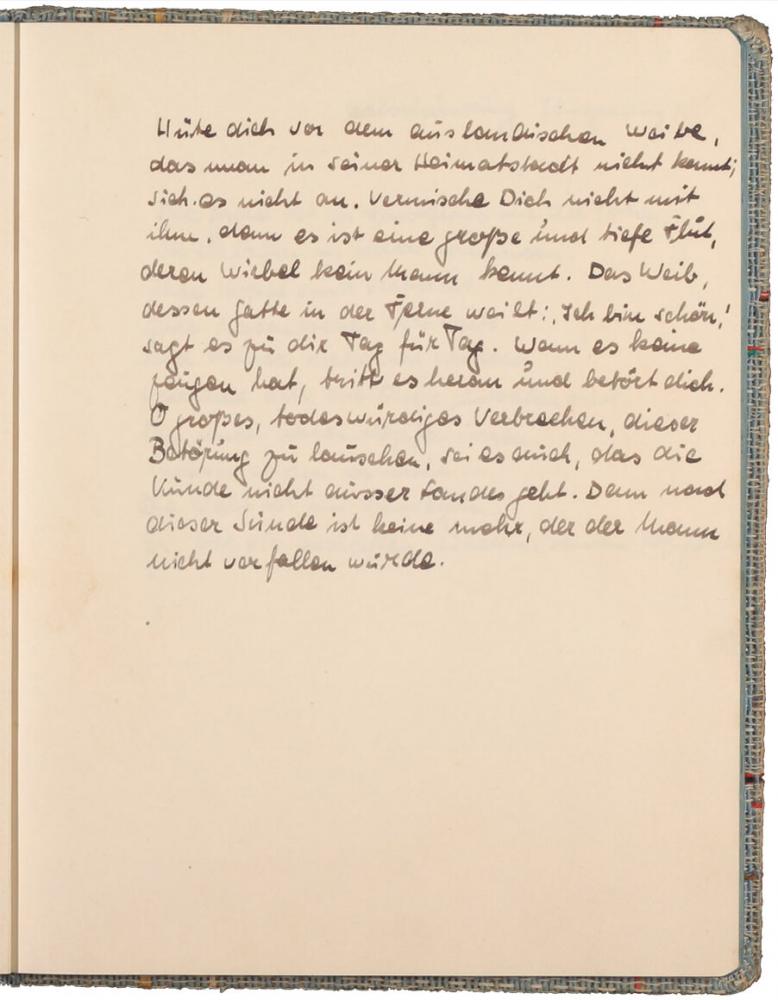

"Guard yourself against the foreign woman

who is unknown in your native town;

do not gaze upon her.

Do not associate with her, for she is a wide and deep flood

whose eddies no man knows.

The woman whose husband is afar tells you 'I am beautiful' day after day.

If there are no witnesses, she comes to you with her charm.

O what an enormous fatal crime to harken to such charms,

even if the tale will not leave the country.

For after committing this sin,

there is none other to which a man would not fall."

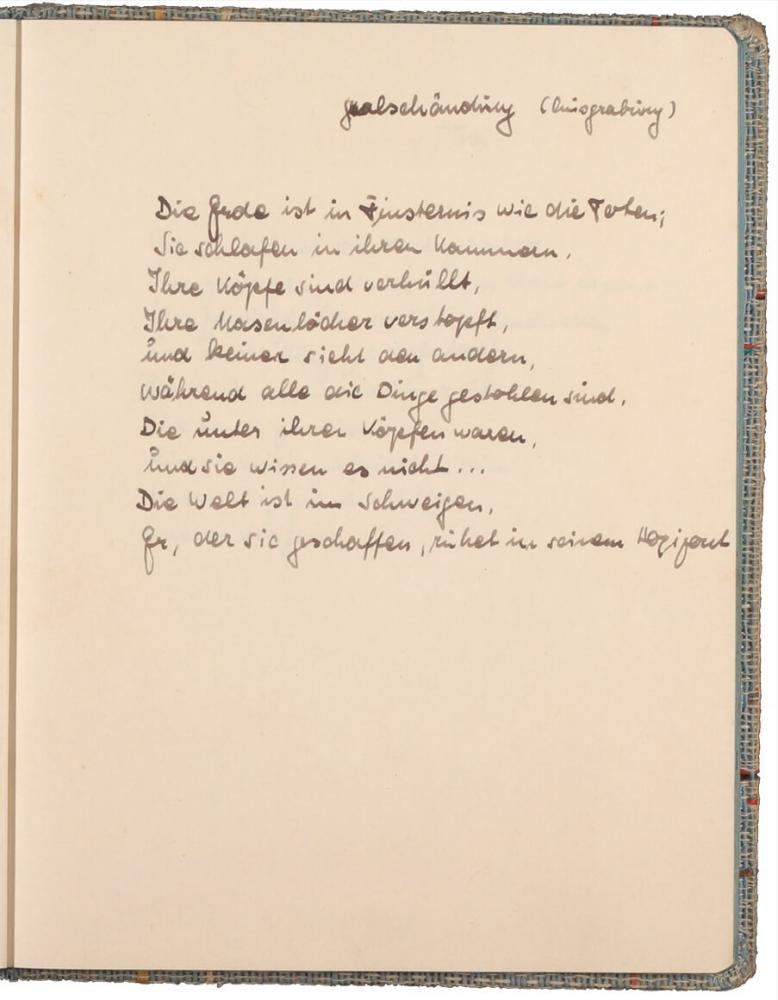

Transkription:

"Grave Robbery

The earth lies in darkness like the dead

Who sleep in their chambers,

Their heads shrouded,

Their nostrils stuffed,

And none can see the others,

While all their things are stolen

From beneath their heads,

And they know nothing of it…

The world is unspeaking,

Its Creator rests in his horizons."

Transkription:

"The Dead

No one returns from there

to tell us how they are faring

to recount to us their fates

and to gratify our hearts.

Till the day we too strike out

to find their land,

we must satisfy ourselves

by encouraging our hearts

to forget."

Transkription:

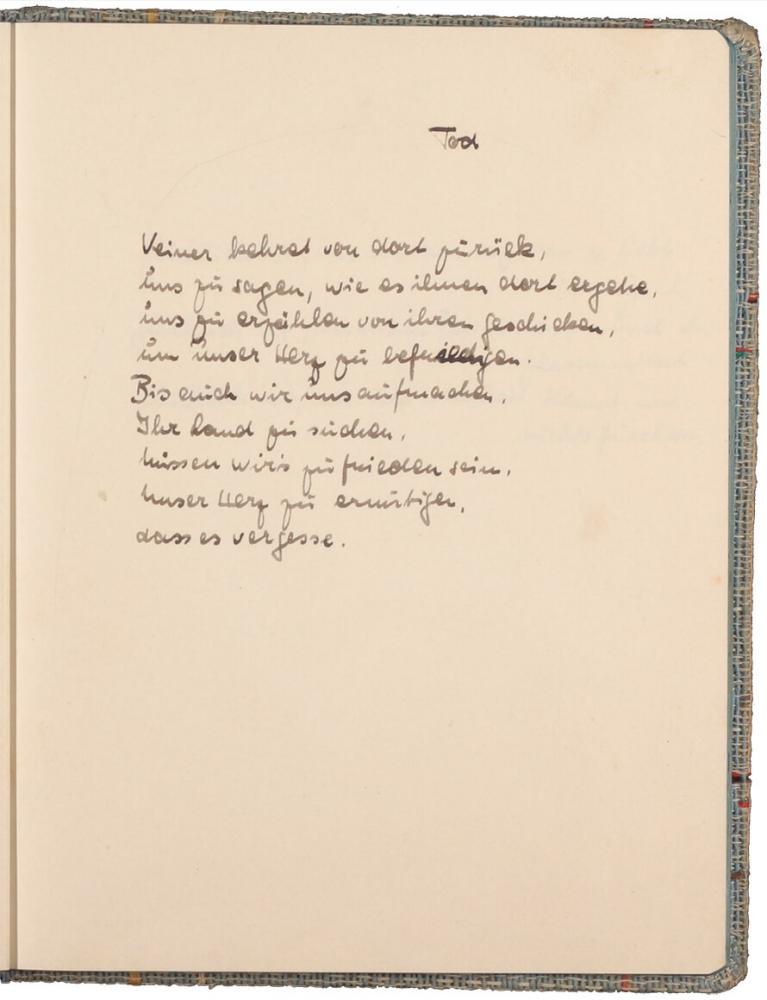

"Happy is he who never betrays his beloved,

Happy is he who knows his enemy and crushes him,

Happy is he who knows the truth and fears not."

Transkription:

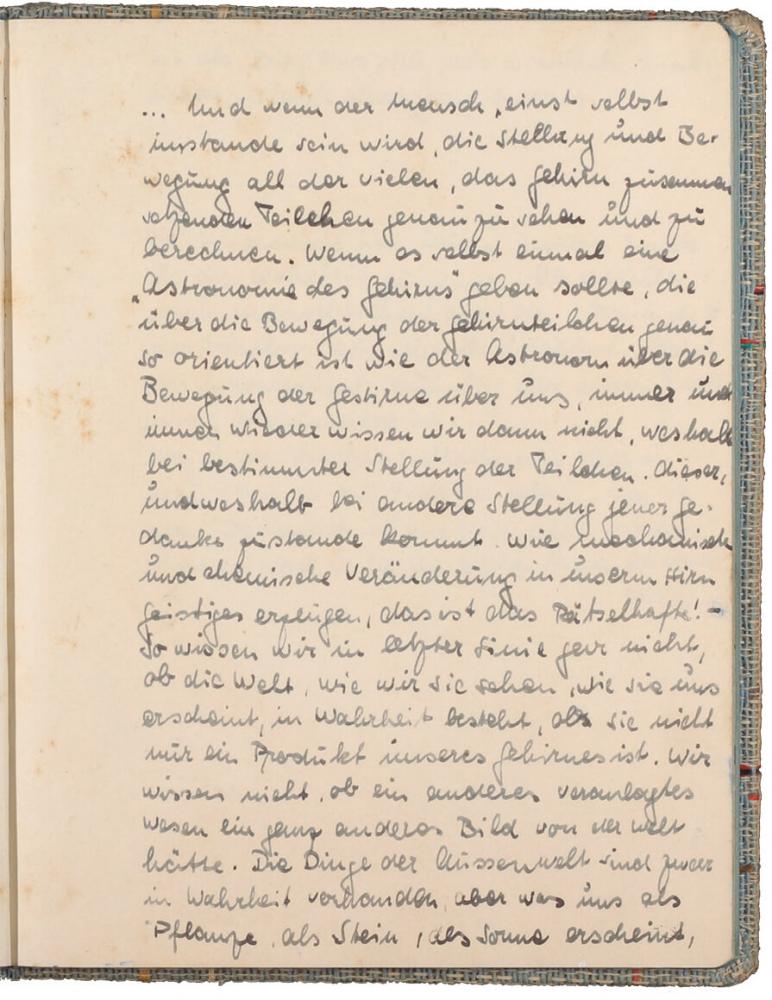

"… And if, one day, mankind will even be able to see and calculate the positions and movements of all the many particles that make up the brain. If someday, there is an 'astronomy of the brain' as well attuned to the movements of brain particles as is an astronomer to the movements of the stars above, even then we would still not know why a particular configuration of particles should produce this thought and another configuration produce that thought. How do mechanical and chemical changes in our brain bring intellect, that is the enigma! Fundamentally, we do not know whether the world truly exists as we see it, as it appears to us, or is merely a product of our brain. We do not know whether a creature of another kind would have an entirely different picture of the world. The objects of the exterior world are truly present, but what appears to us as a plant, as a rock, as the sun"

Transkription:

"is perhaps, as an entity, in its true essence, something entirely different.

The purpose of science is simply to find the truth – no matter whether, to human perceptions, that truth is soothing or bleak, beautiful or unaesthetic, logical or inconsistent, reasonable or foolish, necessary or marvelous.

The truth may state that there is no purpose in living on earth; it might say that 'human beings are an illness of the earth', but it would still be true in the final analysis."

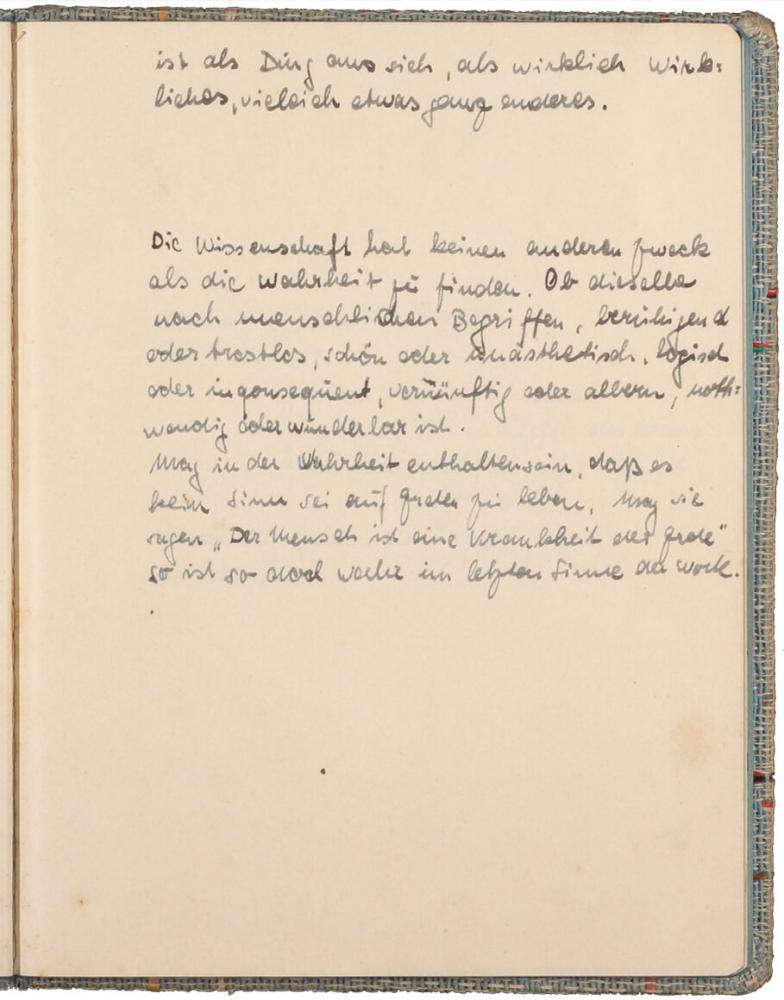

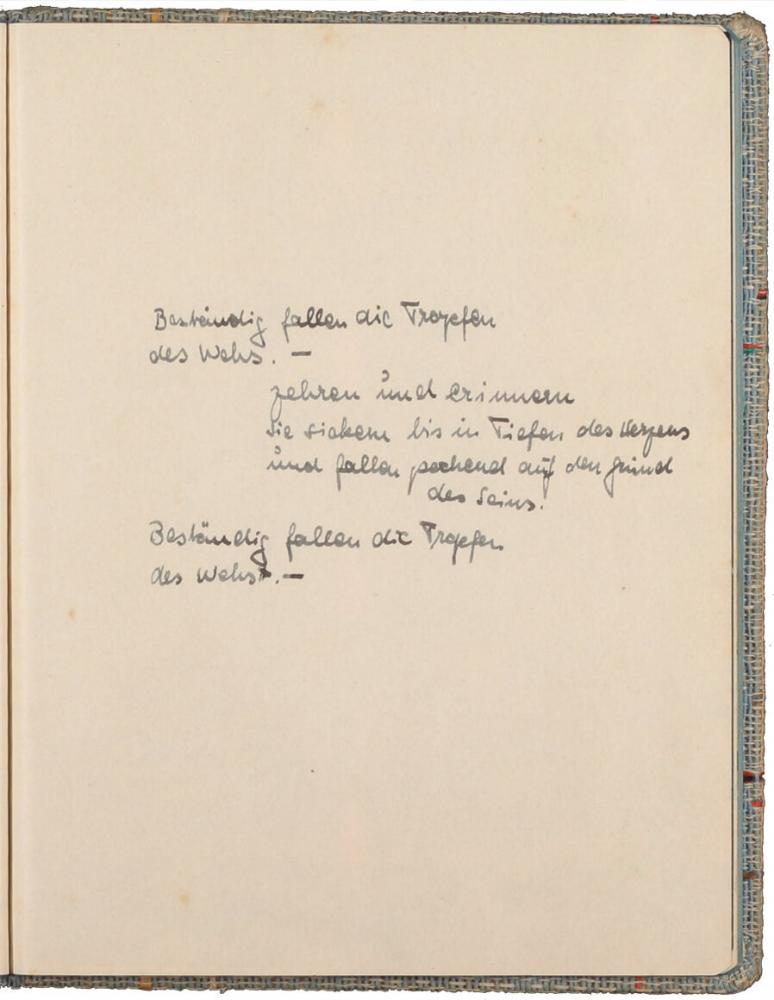

Transkription:

"Steadily fall the droplets

of pain.

Sapping reminders

They trickle into the depths of the heart

and fall throbbing to the floor

of existence.

Steadily fall the droplets

of pain."

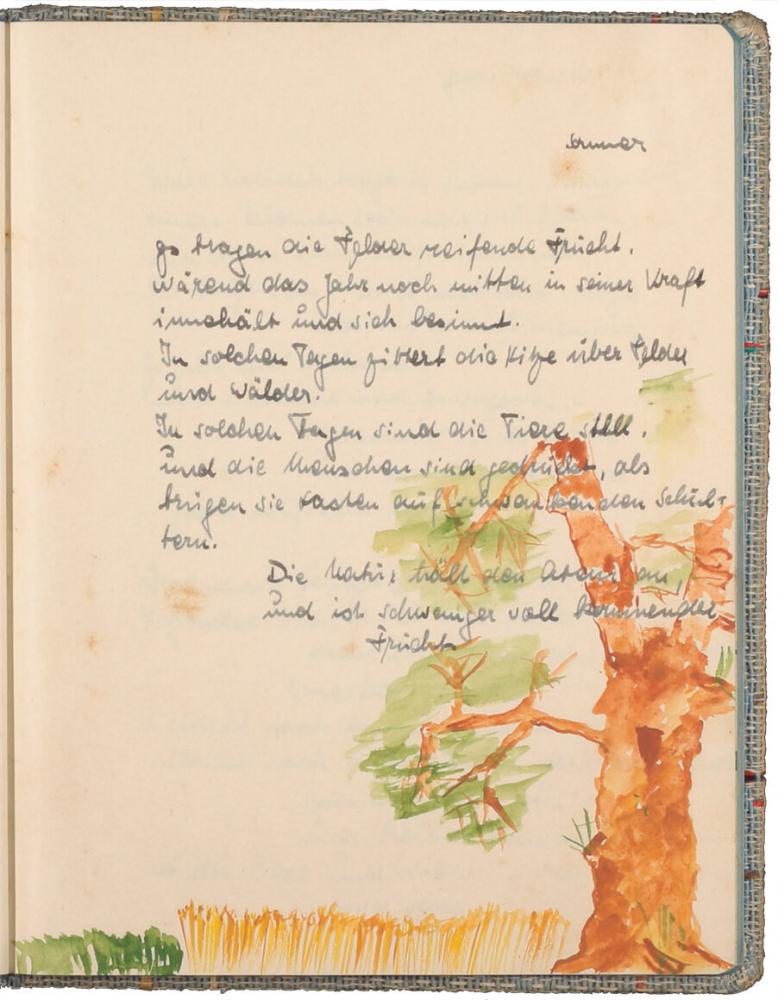

Transkription:

"Summer

The fields bear ripening fruit

while the year, at the peak of its power, pauses and ponders.

On days like these the heat trembles over fields and forests.

On days like these, the animals are quiet

and the people in low moods, as if

carrying burdens on wavering sholders.

Nature holds ist breath

and is pregnant with the fruit to come."

Transkription:

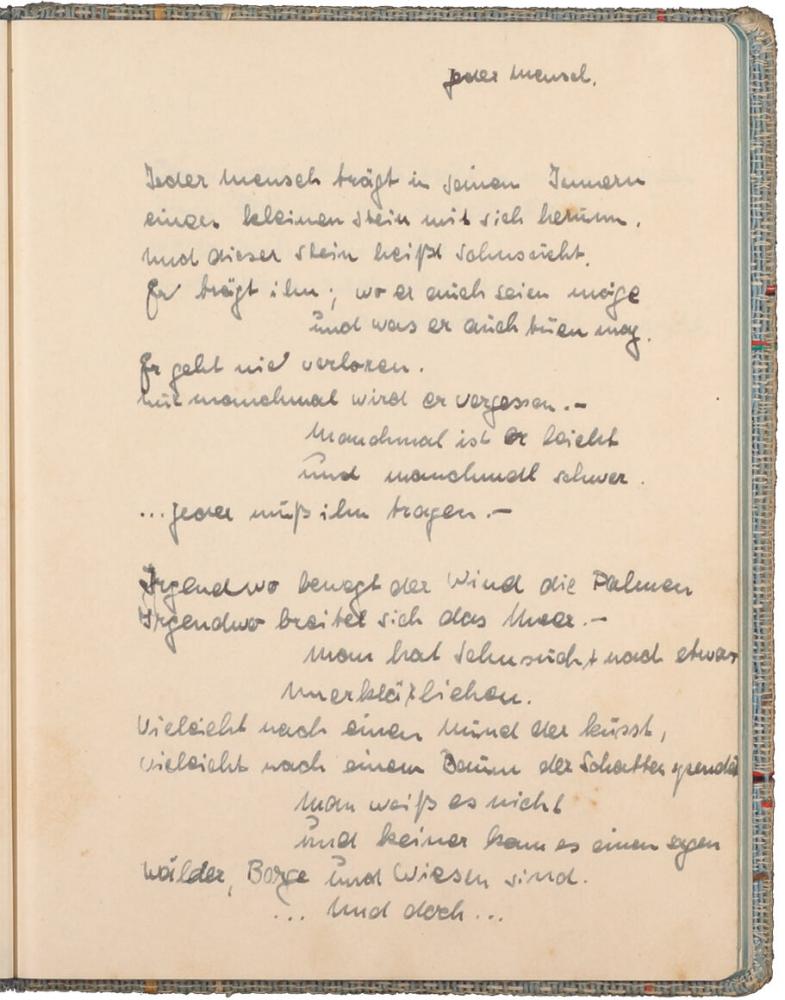

"Each Person

Each person carries around

a little stone inside himself.

And the stone is called longing.

He carries it wherever he may be

and whatever he may do.

It is never lost.

He forgets it only on occasion.

Sometimes it is light

and sometimes heavy.

… Everyone must carry it.

Somewhere the wind whips the palm trees,

somewhere the sea is outspread.

A person longs for something

inexplicable.

Perhaps the kiss of a mouth,

perhaps the shade of a tree.

He does not know

and nobody can tell him.

Forests, mountains, and meadows are…

… And yet…"

Transkription:

"Each person carries around

a little stone inside himself.

He carries it wherever he is

and whatever he does.

And the stone is called longing."

Transkription:

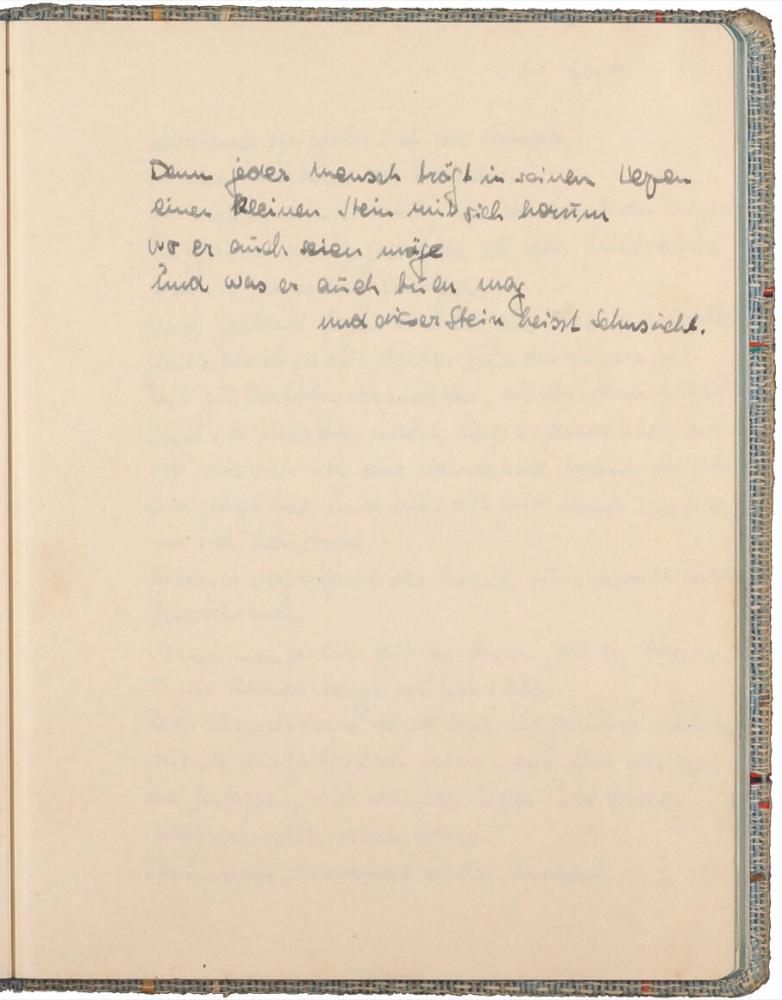

"Time

The screaming lamps reflect each other

in the windows and the streets.

They stand like soldiers at the front

Terror-stricken, prostituting all

that they possess within.

The piercing sounds of traffic ring out

As if attempting with stiff, sore fingers

To stop time from rushing past.

And they do not notice that their haste

has built a stone wall around their existence

and that time is now jolting faster and faster.

Hurried humanity picks up pace with machines

seeking to capture time, which he sees

a scarce arm’s length ahead.

But when his hand is about to grab it,

time jumps, propelled again by his new haste,

faster and faster forward with sore eyes and feet.

Humanity is astonished at the sight."

Transkription:

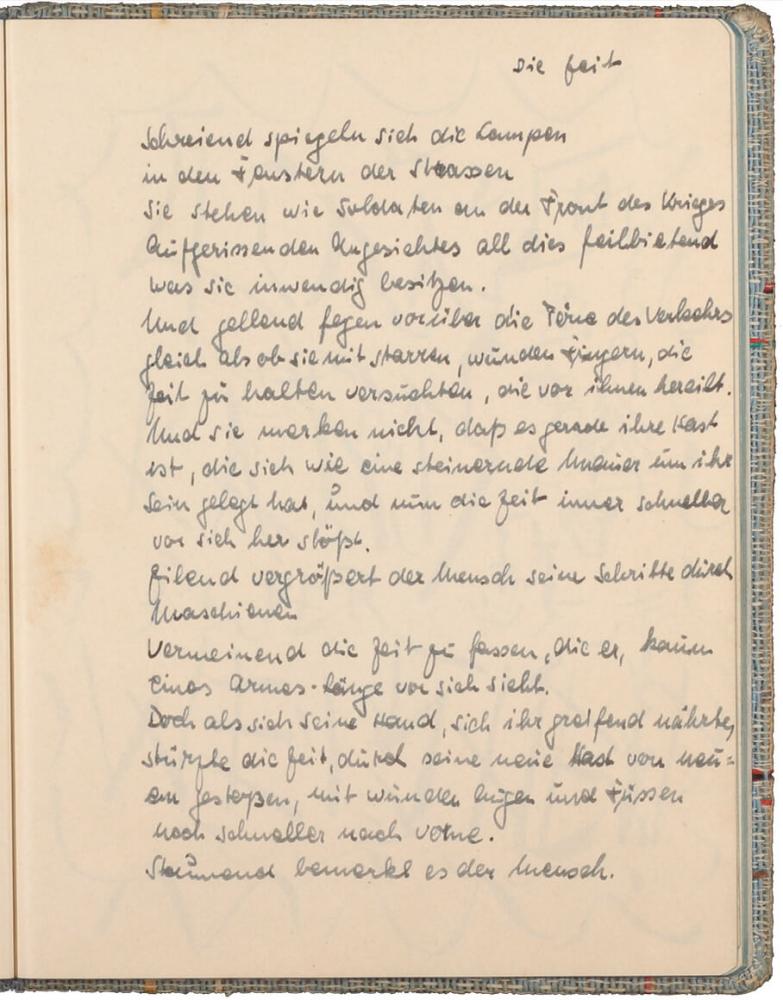

"The Ninth Parable

One cannot hold while pouring;

One cannot whet while touching;

One cannot have while keeping.

Selfishness, unbridled, brings sin.

To work, to complete, living in vacancy:

That is the Path.

Lao Tse"

Transkription:

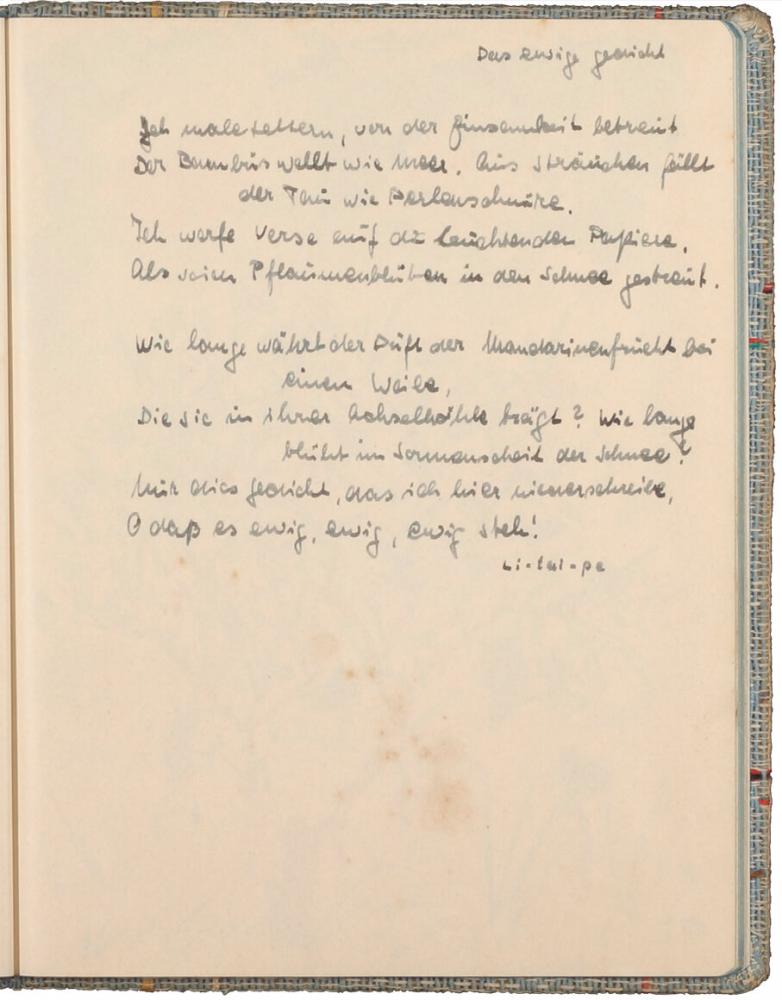

"The Eternal Poem

I paint letters with solitude for company.

The bamboo swells like sea. Shrubs dangle

dewdrops like strings of pearls.

I throw verses onto gleaming paper

like plum blossoms scattered in snow.

How long can the scent of mandarin fruit

linger under a woman’s arms?

How long can the snow

bloom in the sunshine?

Only this poem that I write here,

O, may it last forever, forever, forever!

Li Bai"

[freely translated from Klabund’s German translation]

Transkription:

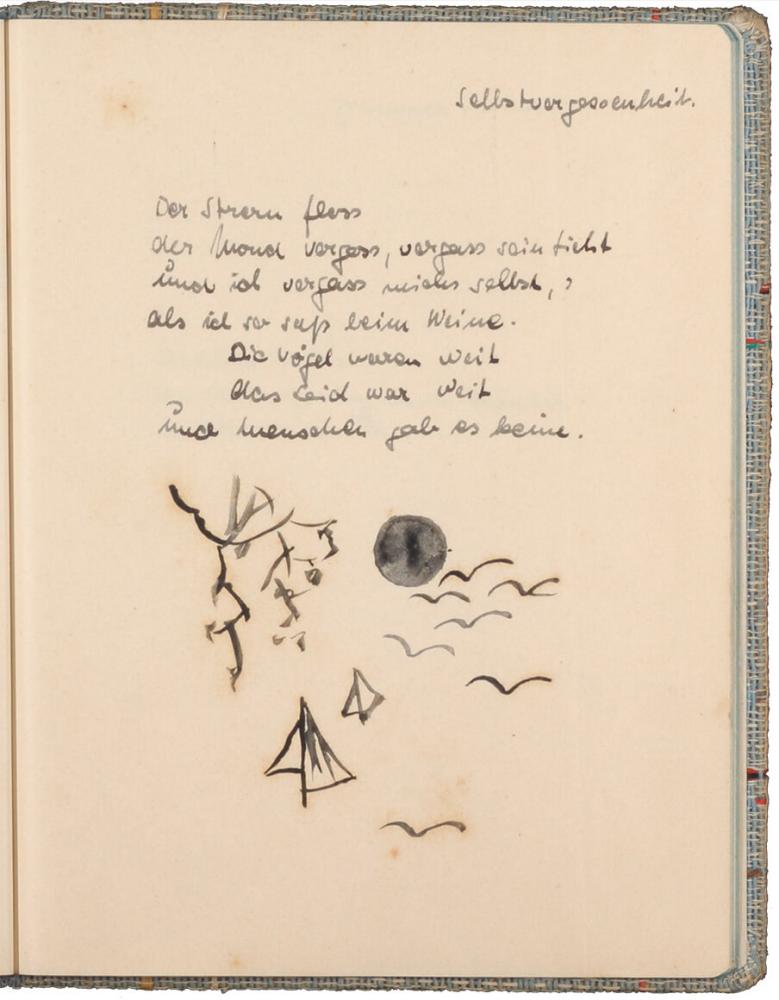

"Self-Abandonment

I sat drinking and did not notice the dusk,

Till falling petals filled the folds of my dress.

Drunken I rose and walked to the moonlit stream;

The birds were gone, and men also few."

[Li Bai, translated by Arthur Waley]

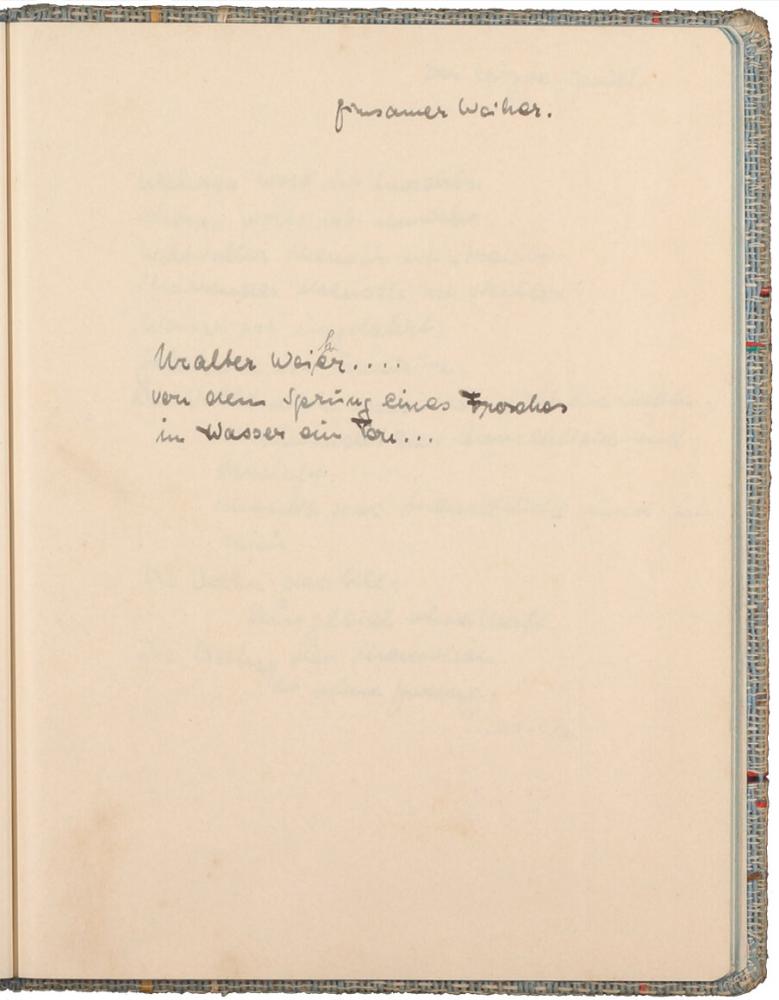

Transkription:

"The lonely pond

The ancient pond

A frog leaps in

The sound of the water."

[Haiku by Matsuo Basho, translated by Donald Keene]

Transkription:

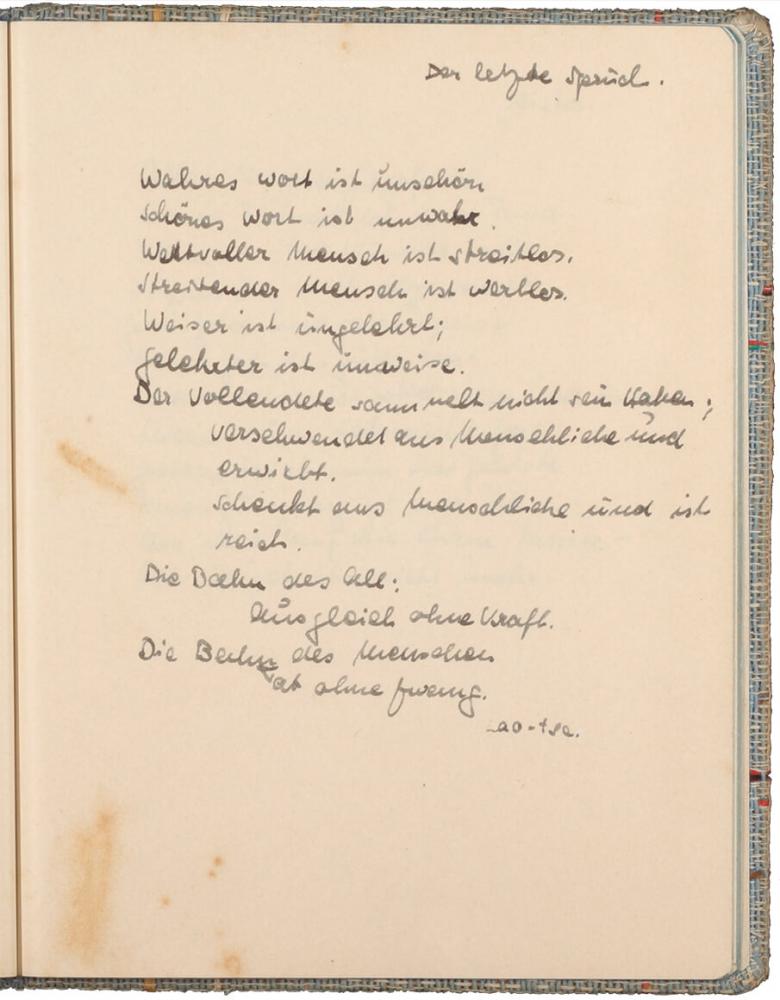

"The Last Word

True words aren’t eloquent;

eloquent words aren't true.

Wise men don't need to prove their point;

men who need to prove their point aren't wise.

The Master has no possessions.

The more he does for others,

the happier he is.

The more he gives to others,

the wealthier he is.

The Tao nourishes by not forcing.

By not dominating, the Master leads.

Lao Tzu"

Transkription:

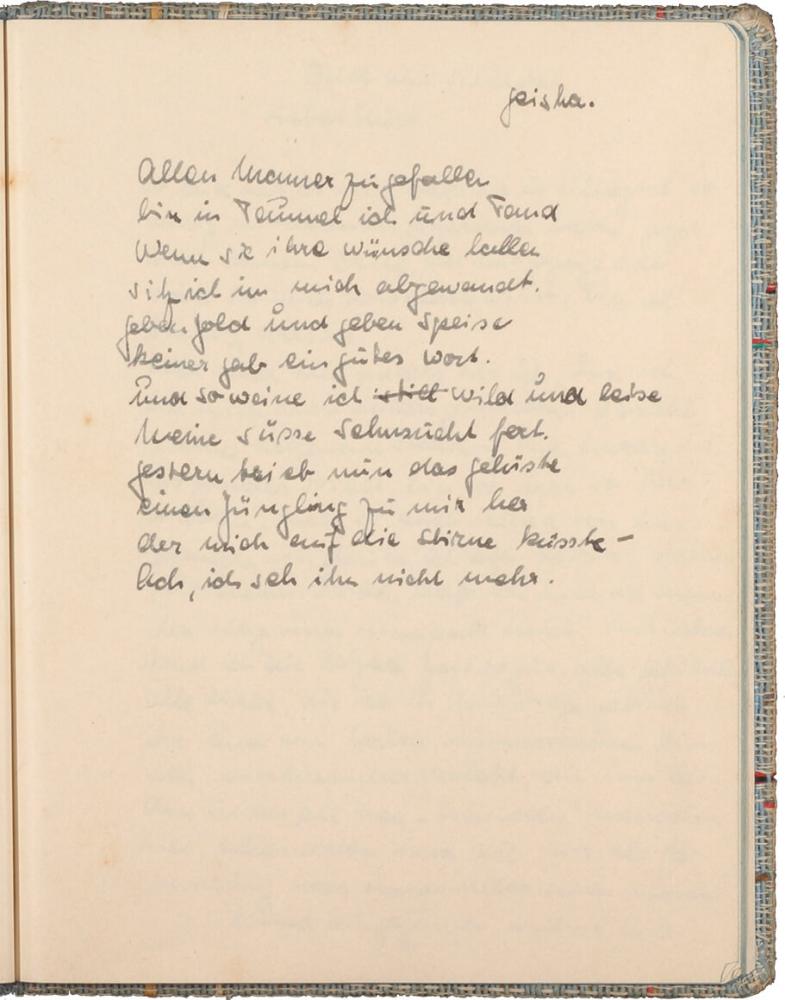

"Geisha

So that all men will like me best

I’m all a whirl and bric-a-brac

But if they’re slurring their requests

I sit aloof and turn my back.

They bring me gold and little morsels

But none have brought a pleasant word.

And so I’m loudly, softly sorrowful

I weep with yearnings sweet, deferred.

Then yesterday a bachelor bowed

Compelled by his magnetic passion.

He left a kiss upon my brow –

I’ll never see his face again."

[Translated from Klabund’s adaptation of the Circle of Chalk by Li Qianfu]

Transkription:

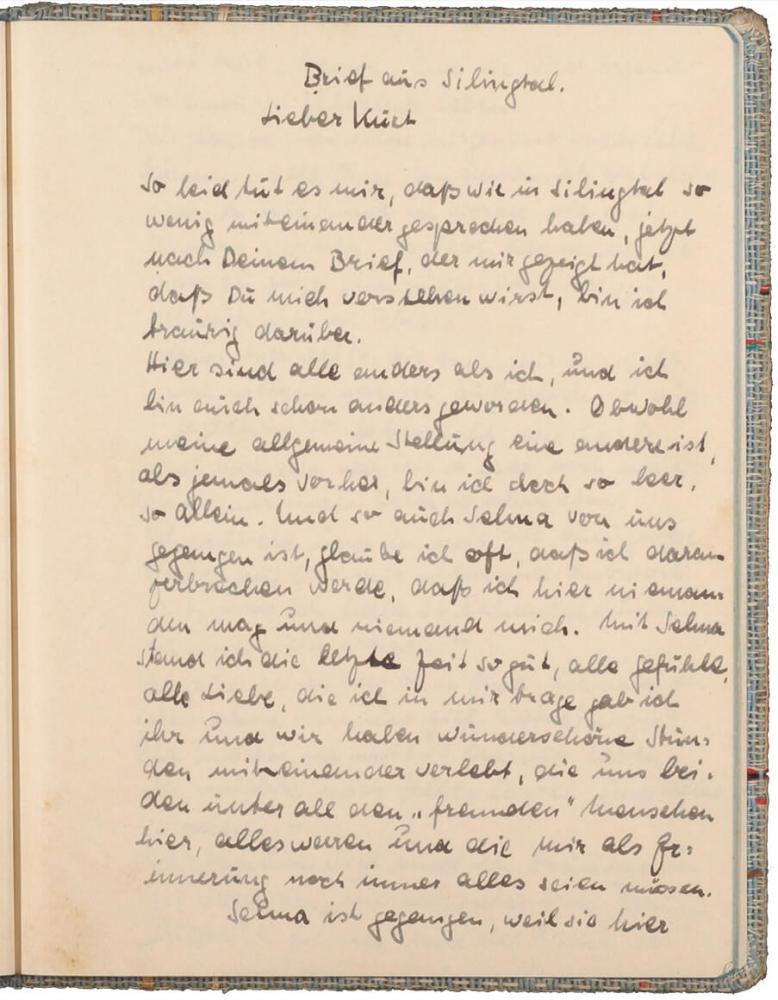

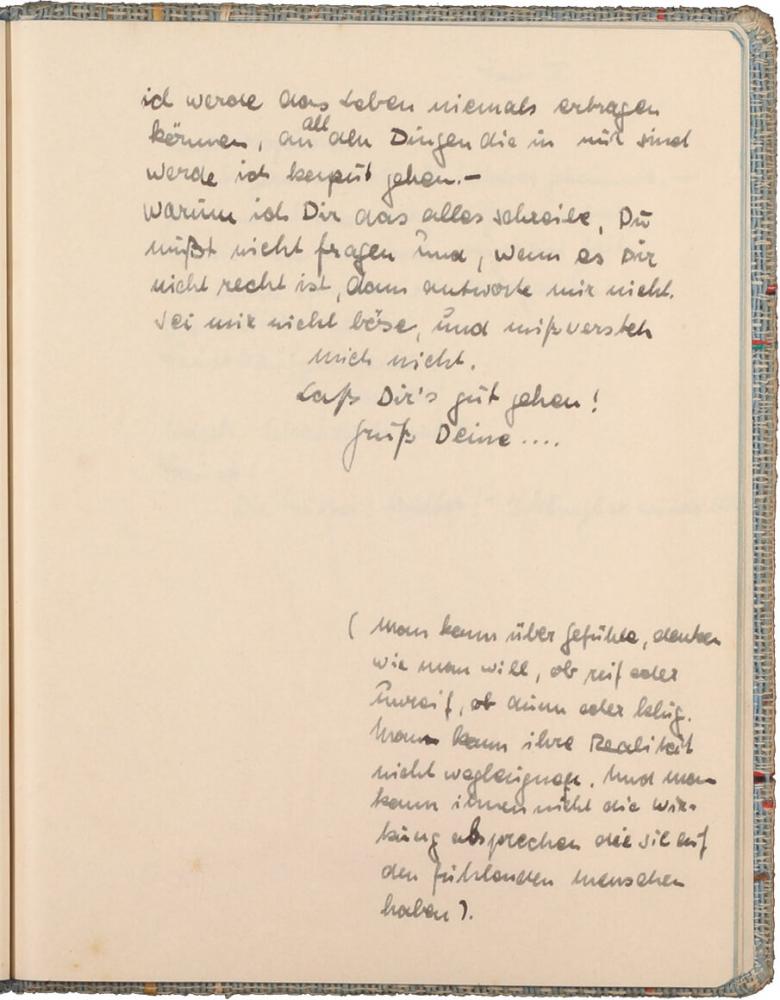

"Letter from Silingtal

Dear Kurt,

I feel terrible that we spoke so little in Silingtal, and now that I saw that your letter showed you would understand me, I’m sad to think of it.

Everyone here is different from me and I have become different too. Although my general status is unlike ever before, I am still so empty, so alone. And since Selma has left us too, I often think it will break me that I don’t like anyone here and no one likes me. With Silma, things were so good recently. I gave to her all the feelings, all the love I carry inside me and we spent beautiful hours together, the two of us among all the “strangers” here, but that was all there was, and must remain all there will be in my memory.

Selma has left because she"

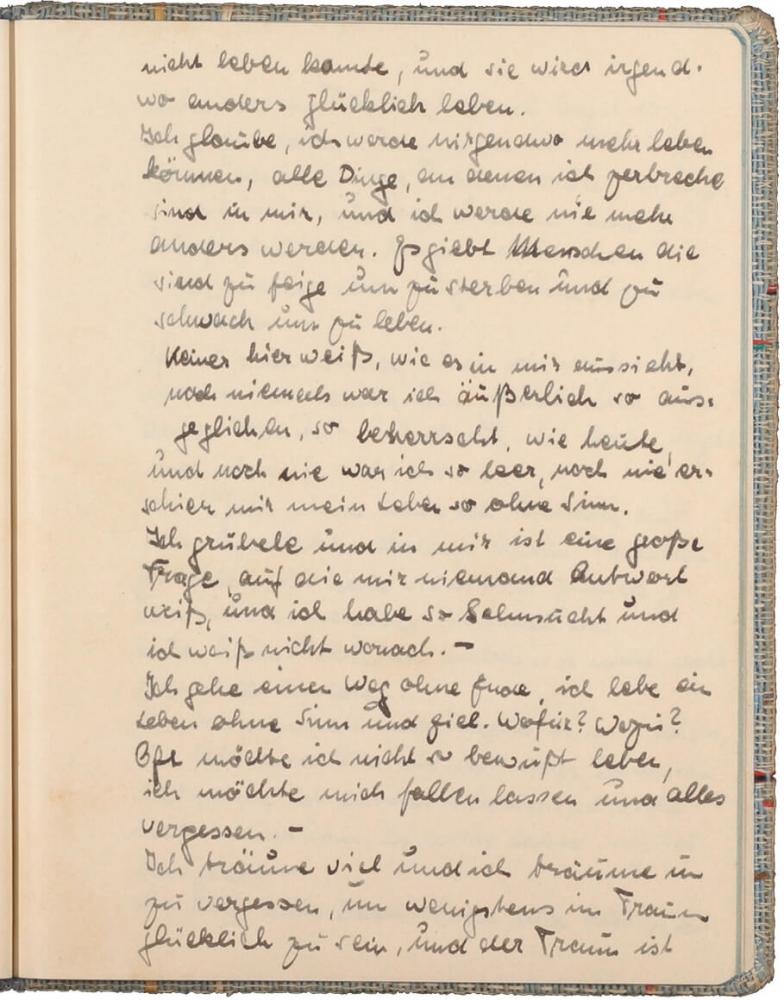

Transkription:

"could not live here and she will live happily somewhere else.

I think I will not be able to live anywhere anymore, all the things that are breaking me are within me and I will never become any different. Some people are too cowardly to die and too weak to live.

Nobody here knows what I’m like on the inside. I’ve never before been so balanced, so in control on the surface as now, and never before so empty; my life has never felt so pointless.

I’m ruminating, and have a big question inside that nobody can answer, I have such longing and I don’t know for what.

I’m walking down an endless path, living a life without meaning or purpose. Why? For what? Oftentimes, I don’t want to live with so much awareness. I want to let go and forget it all. –

I dream a lot and I dream to forget, to be happy at least in my dreams, and the dream is"

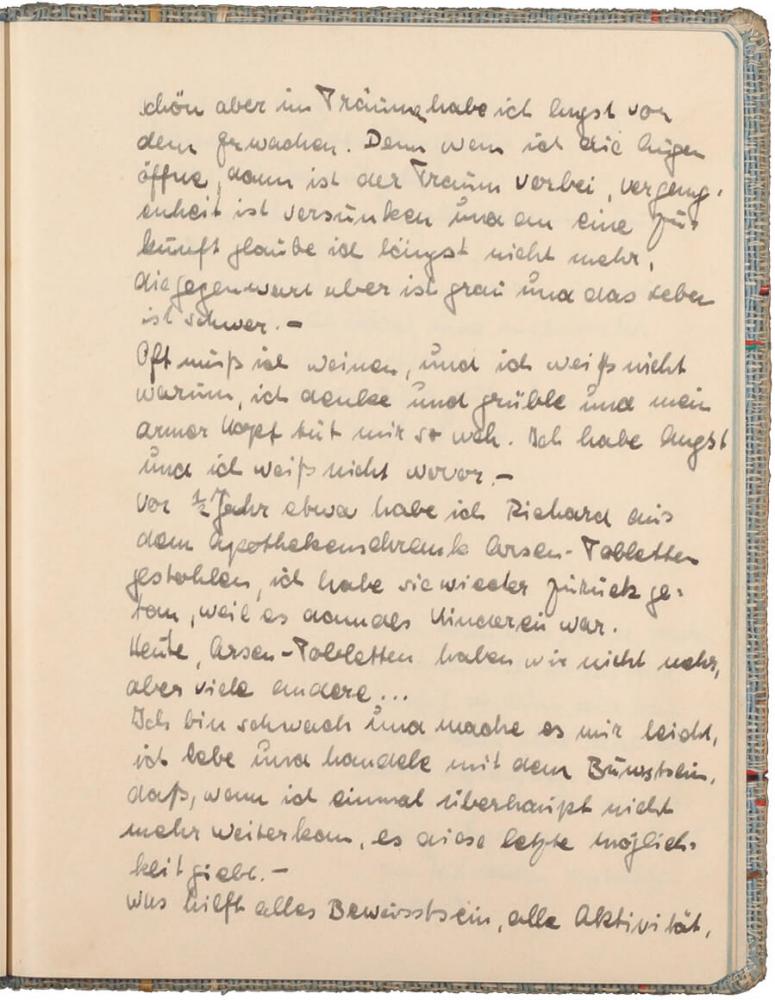

Transkription:

"pleasant, but when dreaming I’m afraid of waking up. Because when I open my eyes, the dream is over, history, has sunk into the depths – and I long ago stopped believing in a future, the present is bleak and life is hard.

I often find myself crying and I don’t know why, I think and I ruminate and my poor head hurts so much. I’m afraid and I don’t know of what.

Half a year ago I stole arsenic tablets from Richard’s medicine cabinet, then I put them back because that was childish back then.

Today we don’t have arsenic tablets, but plenty of other things…

I am weak and I’m taking the easy way out. I’m living and acting with the knowledge if I ever cannot keep going at all, there remains this one last option.

What is all that awareness, all that activity good for?"

Transkription:

"I will never be able to endure life. With all the things inside me, I’ll break.

No need to ask why I am writing all this to you, and if it bothers you, don’t reply. Don’t be angry at me, and don’t misunderstand me.

I wish you all the best!

Yours, …

(One can think what one wishes about feelings, be they ripe or unripe, foolish or wise. One cannot deny their reality. And one cannot negate the effect that they have on a feeling person.)"

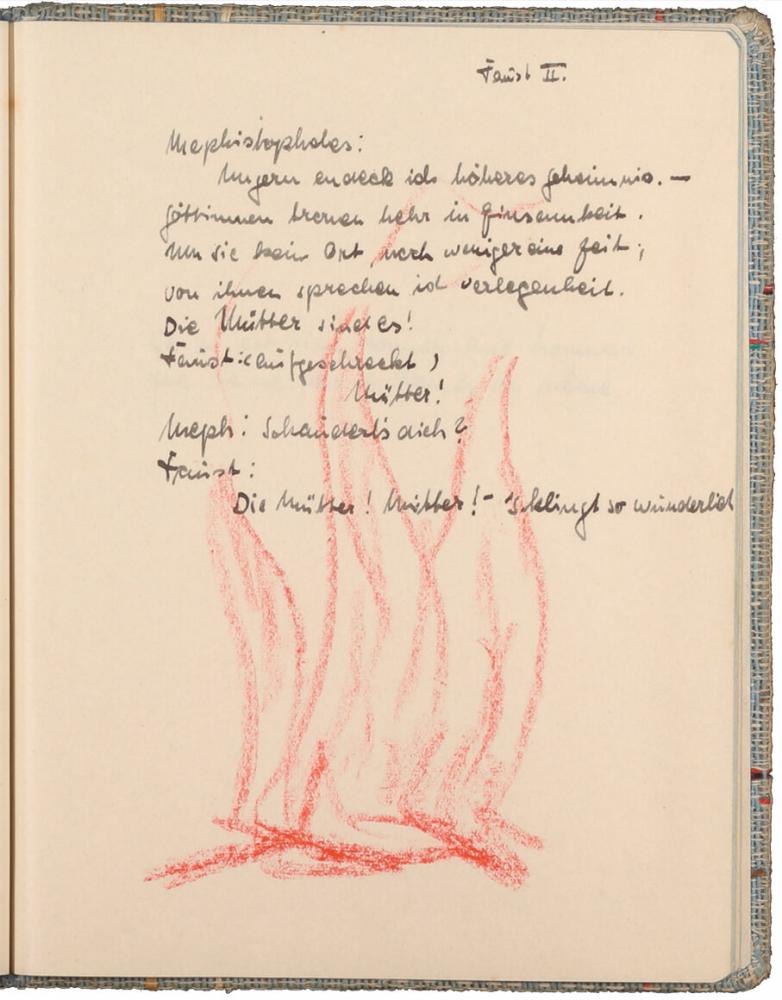

Transkription:

"Faust, Part II

Mephistopheles:

Unwillingly! There’s a greater mystery, I say, Goddesses, enthroned on high, and solitary.

No space round them, not even time: only

To speak of them embarrasses me.

They are The Mothers!

Faust (Terrified.):

Mothers!

Mephistopheles:

Are you afraid?

Faust:

The Mothers! Mothers! It sounds so strange!"

[Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, translated by A.S. Klein]

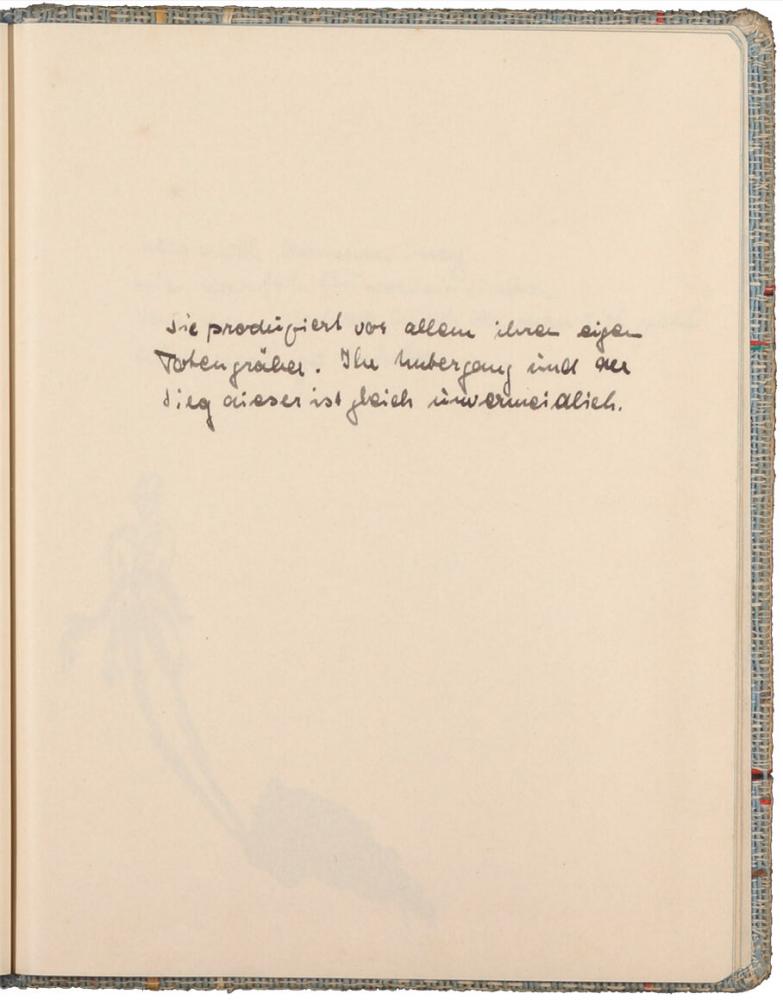

Transkription:

"What it therefore produces, above all, are its own grave-diggers. Its fall and the victory are equally inevitable."

[after Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels]

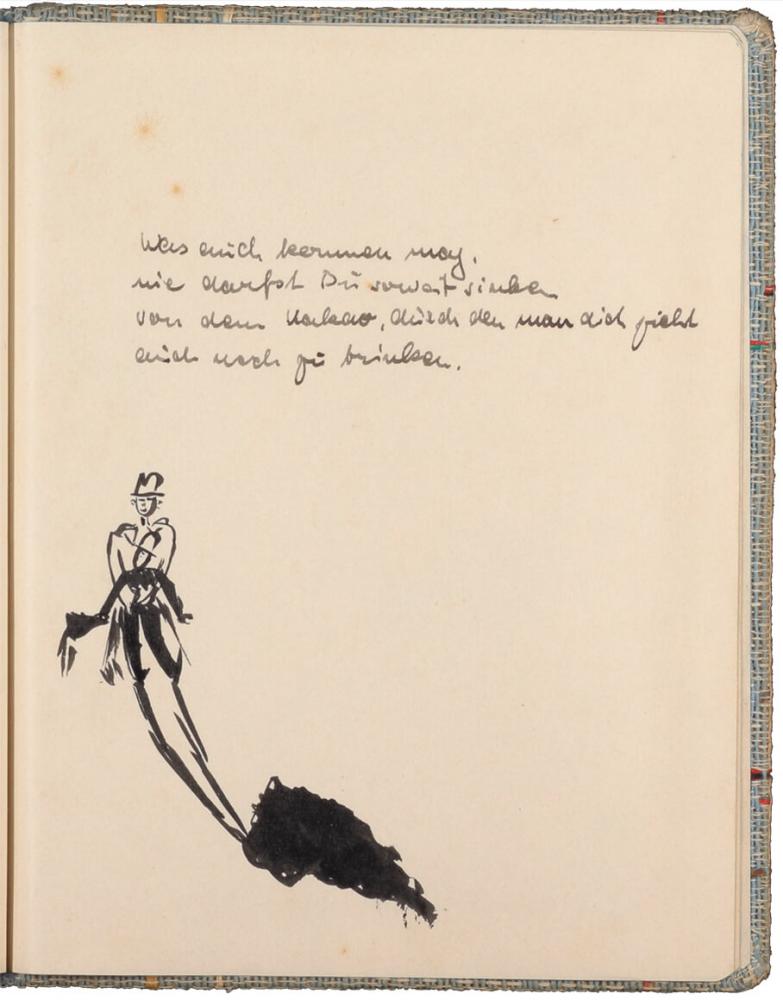

Transkription:

"No matter what should happen,

you must never sink so low

that after being tarred and feathered

you proceed to eat crow."

[after Erich Kästner]

“For Klaus from Kurt”

What was Kurt’s relationship to Klaus? In the beginning, we only knew who Klaus was. Klaus Oliven was born in Berlin in 1918 and emigrated to Brazil in 1939, where he died in 2010. He is at the center of the collection in question, which was donated to us by his children. It contains countless documents from his life as well as many photos depicting him.

But who was Kurt?

Kurt [Unknown]

The book itself contains no further clues as to Kurt’s identity, not even his family name. Perhaps as we indexed the rest of the collection, we would come across more leads to help resolve his identity?

X

X

Portrait of Klaus Oliven, photograph by Margot Neuding, Dresden, 1938; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2016/15/8, gift of the Oliven family

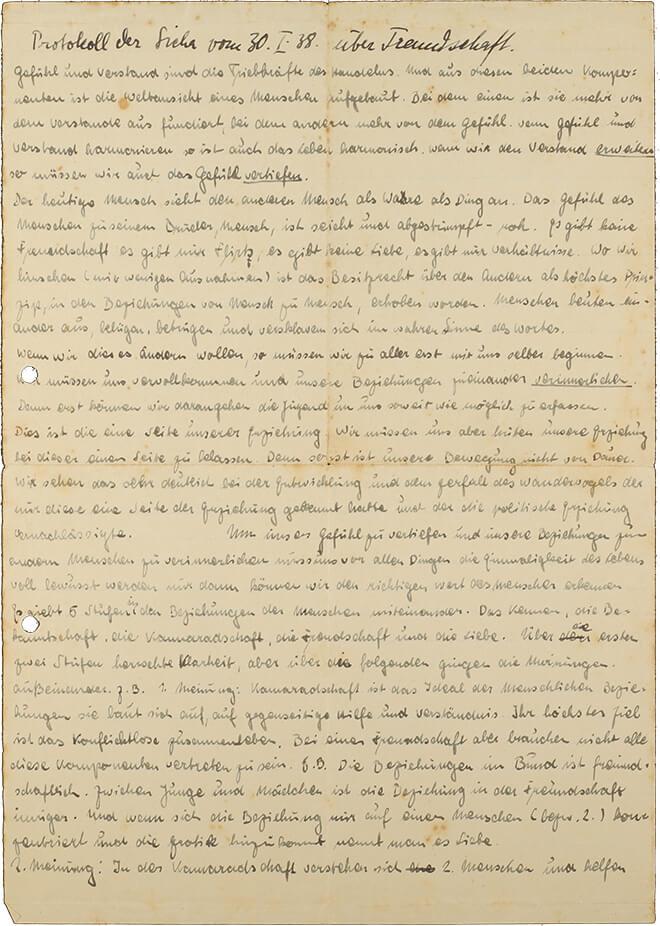

Sicha on Friendship

And so, the inventory process continued. A few days later, we unearthed a stack of minutes from meetings of Hashomer Hatzair, a Jewish youth movement, held in Frankurt am Main in 1937 and 1938. Other documents show that at that time, Klaus Oliven was the leader of the Frankfurt chapter whose discussion group went by the Hebrew name Sicha (conversation).

The Minutes of the Sicha from 30 Jan 38 on Friendship deal with various interpersonal relationships - comradery, friendship, flirtation, and love:

“The modern person views another person as a product, an object... There is no such thing as friendship, only flirtations; no such thing as love, only affaires.”

Aren’t those the very same themes as in the little book, All for Love? The handwriting seems familiar too. And sure enough! The minutes are signed by a “Kurt Friedmann,” who was clearly also living in Frankfurt in 1938.

X

X

Notes on the Sicha about friendship, first page, 30 January 1938; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2016/15/7, gift of the Oliven family

Kurt Friedmann’s signature beneath the notes (detail), 30 January 1938; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2016/15/7, gift of the Oliven family

Nine Different Kurts

This was, then, a sufficient basis for searching the List of Jewish Residents in Germany 1933-1945, a database of the German Federal Archives, which is now in its eleventh edition and is continuously amended and periodically revised.

The database contains nine entries on people by the name of Kurt Friedmann and two others with the spelling Curt. The oldest was born in 1877, the youngest in 1938. The Kurt in question would have been born between 1918 and 1925, we hypothesized. Unfortunately, none of the individuals from the List of Jewish Residents in Germany 1933-1945 matches that age range, and neither did any of them reside in Frankfurt am Main. Ah well; a dead end.

Diaries as a Source

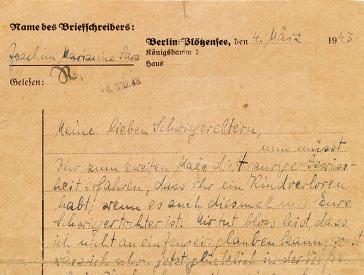

As such, we could only hope that the Oliven Collection, which includes fourteen diaries by Klaus, would furnish more clues. Klaus Oliven wrote at length in his diaries about his involvement in Jewish youth movements, beginning at Habonim Noar Chaluzi and moving over to Hashomer Hatzair in 1936.

His descriptions reveal many interesting details about life in the association, the Bundist vision of education, discussions about issues and ideology, and group activities such as field trips and evening gatherings. The diaries also mention that the 19-year-old Klaus traveled from Berlin to Frankfurt am Main in October 1937 to lead the local chapter, called the “Ken.”

And finally Kurt Friedmann reappears:

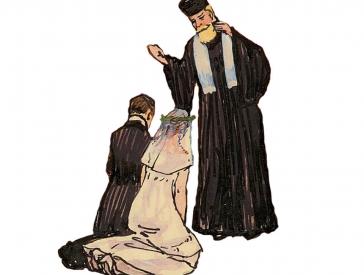

“Kurt Friedmann developed an immediate fondness for me. [...] When I arrived, he was 17 and he later turned 18. A handsome boy, completely blond, but he had very blemished skin, a pimply face. He spoke in authentic Frankfurt dialect. A highly intelligent boy with a mind of his own and also artistic talents. He was good at drawing and made little books of poems and drawings for his good friends... He made one for me too, a long time after I left Frankfurt. A very peculiar, unusual boy, but the only one of them all who was really worth his salt.”

A “little book of poems and drawings”

? Just like the little book All For Love, which you can peruse above?

X

X

One of Klaus Oliven’s diaries; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2016/15/10, gift of the Oliven family

Diary entry by Klaus Oliven mentioning Kurt Friedmann, diary no. 7 (exzerpt), Porto Alegre, 17 March 1940; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2016/15/10, gift of the Oliven family

A False Lead

Invigorated by these new discoveries, our researcher tried once more to track down Kurt Friedmann. A subscription-based genealogy website did indeed reveal a private family tree listing a Kurt Friedmann who was born in 1920 in Wiesbaden and died in 2005. Wiesbaden is not far from Frankfurt. Perhaps this was our man?

The first search result for “Kurt Friedmann 2005 Wiesbaden” was a publication from Wiesbaden titled Poems in Dialect by Kurt Friedmann, raising hopes of a match: poems sounded like the right Kurt, as did the use of (Hessian) dialect. But the genealogist who had created the family tree in question responded promptly, crushing our hopes: this Kurt Friedmann was his father, and was “not Jewish.”

Puzzle Pieces

Alas, it was back to the drawing board and to Klaus Oliven’s diaries, hoping for more mentions of Kurt Friedmann. And sure enough, like puzzle pieces, scraps of information gradually fit together to form a vague picture of Kurt Friedmann from the perspective of his friend Klaus:

Favorite Books

Kurt and Klaus shared a love of literature. Together with some other friends, their chaverim and chaverot, they read Goethe’s Faust, each playing different parts. Perhaps that is how the Goethe quotation “All for Love”

made it on the cover of the little book? The two of them also read the Communist Manifesto together.

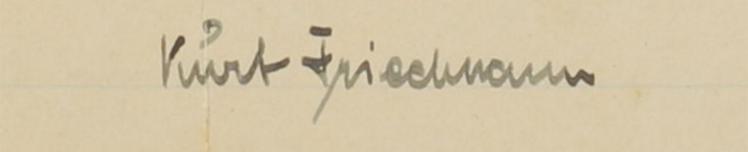

Two-page spread from a photo album with four photos of the “Frankfurt Bund,” 1937/38

(Showing Kurt Friedmann, Fredi Katz [1921–41, murdered in Kaunas], Hans Löwenstamm, Erich Moses, Chajim Pinkus, Grete Schaumberg [1920–41, murdered in Riga], Ruth Sichel [1920-?], and Rony [last name unknown]); Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2016/417/40, gift of the Oliven family

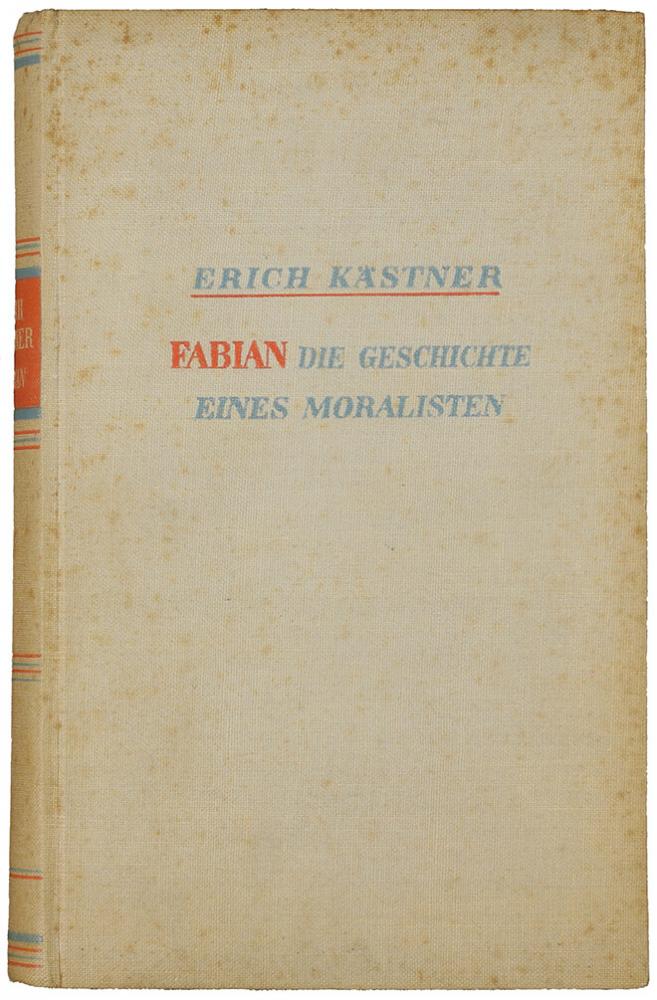

Before Klaus Oliven left Frankfurt in 1938, the members of Hashomer Hatzair organized a “nice farewell neshef with shmonzes,” or a literary evening at Kurt’s house. Kurt suggested that each member read their three favorite passages from their favorite books. Kurt’s favorite books were Fabian by Erich Kästner and Children of Pain by Georg Fink.

At the Hakhshara

Klaus was not the only one leaving Frankfurt. Kurt left as well to attend the Intermediate Hakhshara. The Intermediate Hakhshara prepared teenagers from fifteen to seventeen for emigrating to Palestine by training them in agriculture and skilled labor.

First there was significant resistance to overcome. Hans, Kurt’s previous group leader, “did not think much of Kurt and we had completely different views of him.” But Klaus advocated for him and eventually also convinced Kurt’s parents of the idea.

X

X

Fabian: The Story of a Moralist by Erich Kästner, 1931 edition, Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt (book cover designed by Georg Salter); Jewish Museum Berlin, accession BIB/836/0, gift of George Warburg

Because the Friedmanns were penniless, the Jewish Community had to provide a scholarship. Finally, Kurt was invited to a farm in Silingtal. Silingtal? Where is that? It took an inter-library loan through our colleagues at the Museum Library to locate it: Silingtal was a little-known teaching farm for prospective emigrants located near the village of Klein Silsterwitz in Lower Silesia. It was presumably the only Hakhshara camp operated by Hashomer Hatzair at the time.

Departure from Frankfurt

On 1 March 1938, the two friends parted ways. Klaus returned to his family in Berlin, then continued onward to Dresden. Meanwhile, Kurt traveled to Silingtal.

“He left the same night as I did, only five minutes later... He was going to the Hakhshara with great expectations. He had resolved to start a new life there and wanted to leave Frankfurt as soon as possible because Dorle had left for America a few days earlier, which hit him hard of course, after a girlfriend he had loved very much had already been taken from him in the same way.”

Dorle was Kurt’s fifteen-year-old girlfriend who had worked at his mother’s hat shop. In his diary, Klaus wrote that Kurt had trusted him with “strictly confidential,”

intimate details of their relationship.

“The Book Speaks for Itself”

The two friends stayed in contact after they both left Frankfurt. This is how we know that Kurt was unhappy in Silingtal and in particular had issues with its director, whom he perceived as a dictator. “It was a pity that Kurt couldn’t find his place there,”

wrote Klaus in his diary.

Kurt did not linger long. Within a matter of months, he was making his way back to Frankfurt. By then, Klaus was living in Dresden and had gotten together with a new girlfriend, who was named Margot and known as Spatz. “Kurt told Spatz so many nice things about me from Frankfurt etc. that she was shocked that a boy could gush about me so wildly.”

In turn, Klaus was impressed with Kurt and described him as a “boy who, while peculiar, is so talented and impressionable. He has something girlish, enthusiastic, and soft about him.”

The two of them continued their correspondence, although Kurt did so in secret because his family disapproved of his friendship with Klaus. He worked in Frankfurt. With his wages, he barely kept above water. Klaus helped him out and gave him a knickerbocker suit as a gift.

“From Frankfurt, he finally sent me the little book he’d promised me ever since we parted in Frankfurt.... He’d made one like it for all the people he really liked.... The book speaks for itself and I will take very good care of it.”

Klaus kept that resolution for a lifetime.

“Dearest שלום”

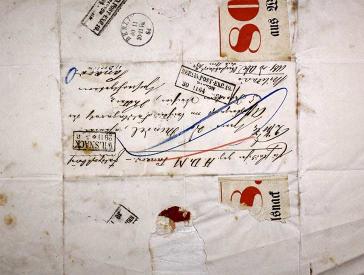

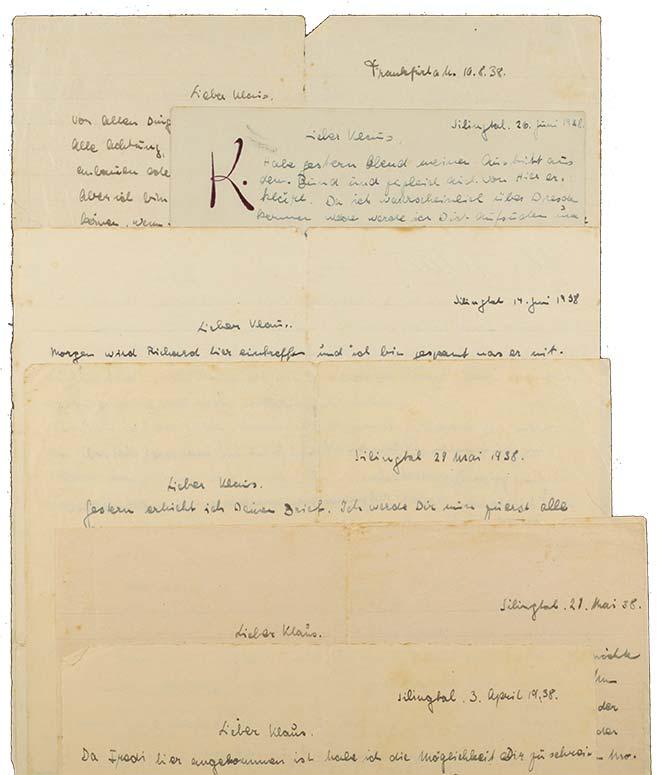

Some of the correspondence between Kurt and Klaus has been preserved in the Oliven Collection: five letters and a postcard that Kurt wrote between 3 April and 10 August 1938, almost all of them sent from Silingtal. The final letter was the only one he wrote from Frankfurt am Main, which he sent together with the little book All for Love: “Enclosed, the long-awaited book.”

Kurt had sent one of the earlier letters from Silingtal together with a letter to his parents, asking Klaus a favor:

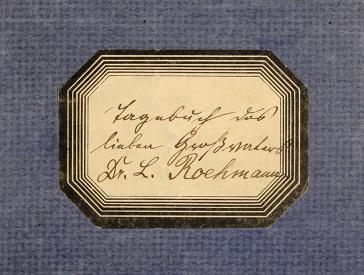

“Could you be so kind as to put it in an envelope and send it to Isaak Friedmann in Frankfurt, Eschersheimerlandstr. 5.”

X

X

Letters from Kurt Friedmann to Klaus Oliven, Silingtal and Frankfurt am Main, 3 April to 10 August 1938; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession Presse/2699/0, gift of the Oliven family

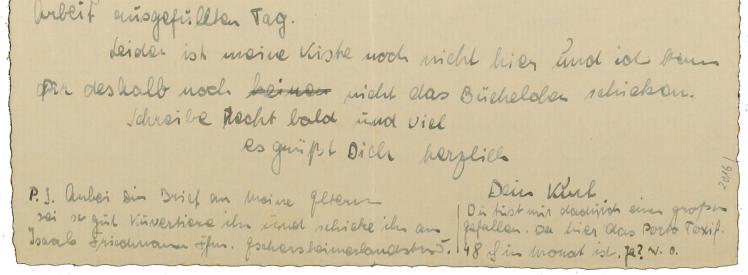

Postscript by Kurt Friedmann at the end of his letter, Silingtal, 3 April 1938; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2016/15/9, gift of the Oliven family

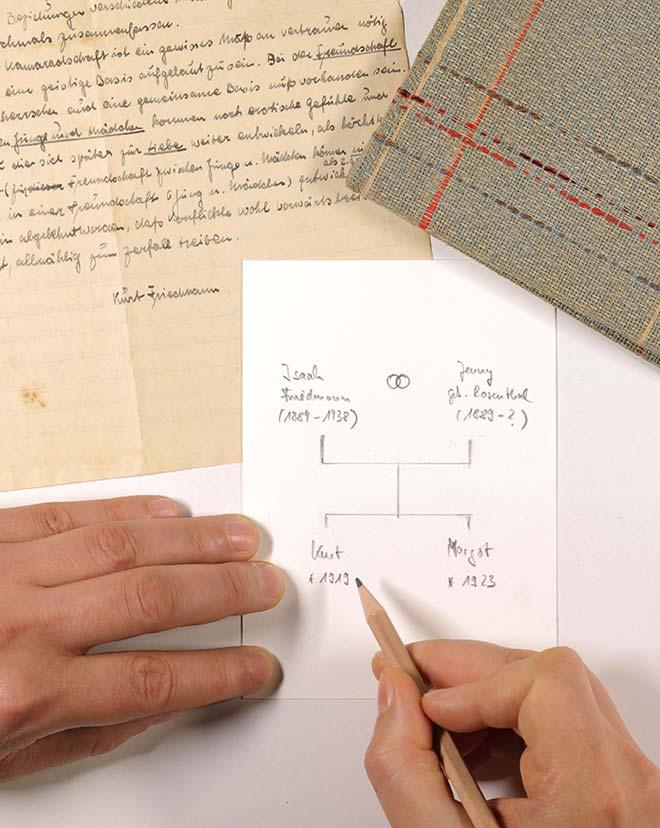

This was our researcher’s stroke of luck. Finally, a new lead! This specific address made it possible to send an inquiry to the Institute of City History in Frankfurt am Main, which responded that same day: Kurt Josef Friedmann was born on 21 September 1919 and had a sister named Margot who was four years younger than him. His mother Jenny Friedmann ran a clothing store on Hochstrasse 4. In 1934, the family moved to Eschersheimer Landstrasse. His father Isaak Friedmann died on 23 September 1938.

Their address registration forms indicated Polish citizenship. The archivist in Frankfurt therefore assumed that the Friedmanns were deported to Poland during the Polenaktion (Polish Action) of October 1938.

Finally, Some Progress!

Thanks to these new leads, we were able to find more information on Kurt’s family via a few detours: A son of Kurt’s cousin, who lives in Jerusalem in her old age, can be found on the Internet. Thankfully, he was able to contact David, the son of Kurt’s sister Margot. David lives in England, and was taken aback by the email from the Jewish Museum Berlin.

X

X

We need a Friedmann family tree to keep track of things; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession Presse/2704/0, photo: Jörg Waßmer

“My Uncle”

David responded:

“Unfortunately my mother passed away some 19 years ago, and when she was alive she did not talk a lot about her life in Germany, maybe she just wanted to try and forget about the horrors. What I do know is that she mentioned that my uncle, whom my father called ‘The Communist’ wished to travel to Russia instead of accompanying my mother and grandmother to England. That’s really where the story ends, as he was never heard from again.... Bizarrely, your email came a week after my wife and I traveled to Yad Vashem in Jerusalem and I tried to gain more information on my uncle whilst we were there. Alas without any success.”

X

X

Portrait of Kurt from the little book All for Love, about 1937 or 1938; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2016/15/322, gift of the Oliven family

Nevertheless, the Archive of the Jewish Museum was able to send him reproductions of two photographs of his mother Margot from one of the photo albums in the Oliven Family Collection. The photos had been pasted in alongside a photo of Kurt with the caption “Kurt’s sister.”

David was stunned. He had never seen a photo of his mother as a young girl before.

Two portraits of Margot Friedmann with dedications on the back: “For you - 3 December 1938” and “Keep me in mind sometimes - 23 February 1939”; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2016/417/42/003 (left) and 2016/417/42/002 (right), gift of the Oliven family

Page of Testimony at Yad Vashem

This exchange also revealed that forty years ago, David had left a Page of Testimony for his uncle at the Israeli memorial museum Yad Vashem. But because it is listed under the name Joseph Friedmann and does not mention his first name Kurt, the Archive staff member had previously been unable to find him in Yad Vashem’s online database.

His 1980 Page of Testimony lists Russia as his presumptive location during the war; meanwhile, the International Tracing Service in Bad Arolsen listed him as “missing” ever since his deportation during the Polenaktion.

Deportation from Germany

Indeed, one of the last people to see Kurt Friedmann in Germany was Klaus Oliven. In the ninth volume of his diaries, he describes the Polenaktion of October 1938, when at least 17,000 Jewish with Polish citizenship residing in the German Reich were arrested, transported to the border, and violently deported. At the time, Klaus was still living in Dresden and experienced the grief of this firsthand:

“Most of the trains passed through Dresden on their way to the Polish border. The community had received authorization from the State Police to set up food and aid at the train station for those passing through.”

Klaus Oliven and his chaverim/-ot signed up as volunteer aid workers. They distributed food such as hot soup, beverages, hygiene items, medicine, and stamped postcards allowing those deported to contact their relatives. Klaus writes:

“Trains also passed through from Frankfurt, and I found many old friends from Frankfurt in one of them. Kurt, his sister Margot, his mother (his father, I found out on the platform, had since died).... The train made a long stop and I had some time to talk to them.... Kurt nearly fell backwards when saw me. He hadn’t expected this.”

Klaus goes on to mention that Margot and her mother returned to Frankfurt: “Only Kurt went over to Poland.”

“We haven’t had a letter from Kurt for four weeks now,”

wrote his sister Margot in December 1938 to Klaus Oliven. “But from others, we’ve heard that sadly he is not doing especially well because he has no work and is living off the Komittée.”

And that was where all traces of Kurt Friedmann, then aged nineteen, ran cold.

Kurt Friedmann climbing on a wall, about 1937 or 1938; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2016/417/42/001, gift of the Oliven family

Remaining Questions

Unfortunately, we have found no leads whatsoever to help us determine where Kurt Friedmann ended up, and we have likely exhausted our options for determining his fate. We have more hope of answering some smaller questions that remained unresolved during the research process described above.

In his diaries, Klaus Oliven mentions in several places that Kurt had sent other friends little books of poems and drawings similar to the one presented here.

- One of those friends was Kurt Sommerfeld, whose identity cannot be conclusively established. There are some indications that he may have committed suicide in exile in London in 1939. It is unclear whether his possessions and papers have been preserved somewhere.

- Bella Reiner, who later married Xiel Federmann, was also mentioned as having received a little book. When the Archive contacted her son in Israel, he informed us that he could not find a little book of that description among her things. (She died in 2011.)

- So far, we have not been able to find out about the later life of Kurt Friedmann’s girlfriend Dorle, who emigrated to the United States. She was also supposed to have received a little book. But we have not been able to find her or any children she may have had.

- Did any of Kurt Friedmann’s other friends receive such books? Have any of them been preserved by the recipients or their heirs?

Can you help? Do you have any other leads?

Jörg Waßmer

Contact

Archive

T +49 (0)30 259 93 318

archive@jmberlin.de

Citation recommendation:

Jörg Waßmer (2018), Kurt. Hunting for Clues.

URL: www.jmberlin.de/en/node/5803

Behind the Scenes: Anecdotes and Exciting Finds while Working with our Collections (22)