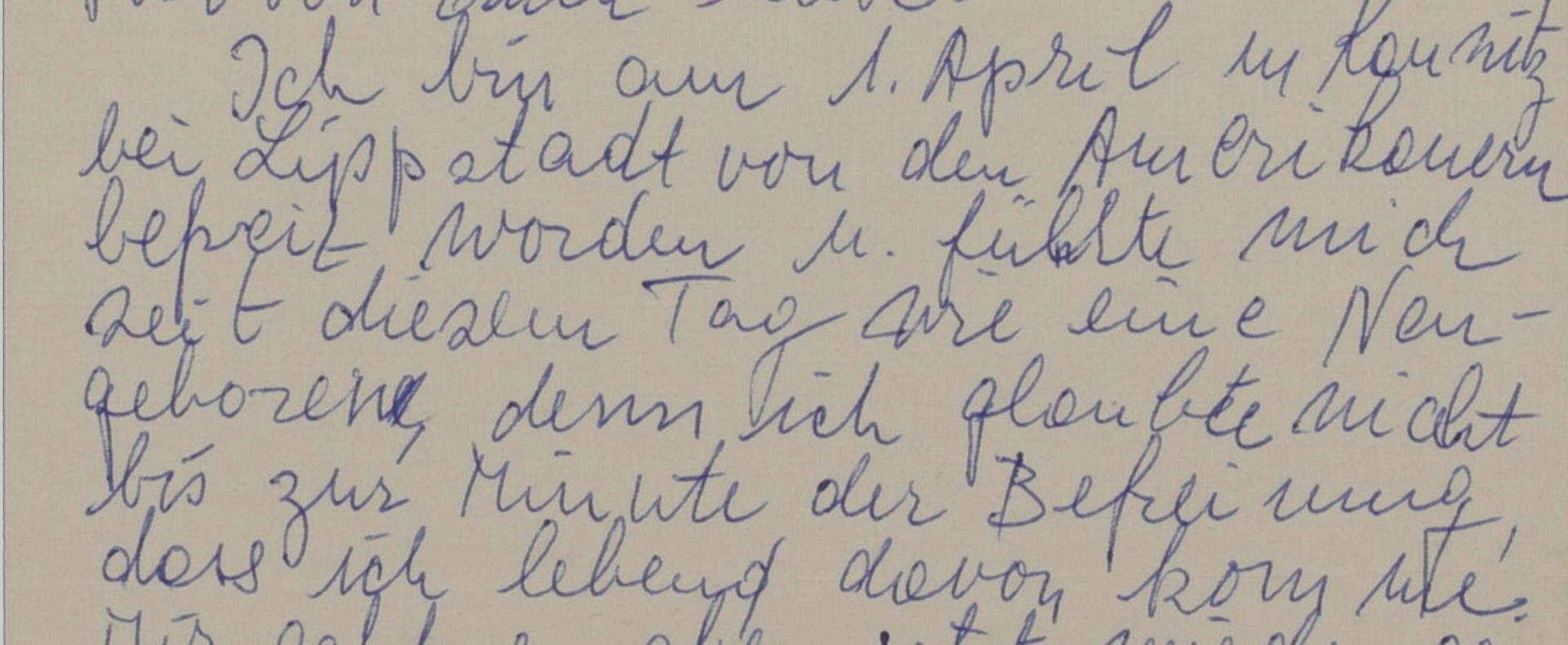

“Since that day, Iʼve felt like a newborn”

A Striking Document from our Collection about the 1945 Day of Liberation

VE Day, the Day of Liberation from National Socialism, celebrates its 75th anniversary on 8 May 2020. Not all Germans experienced the unconditional surrender of the Wehrmacht and with it the end of the Second World War in Europe as an immediate “liberation”—not by any stretch of the imagination. Some were still prisoners of war, while others were pained to see the downfall of an ideology they had believed in or still did.

The outlook was very different for those persecuted by the Nazi regime:

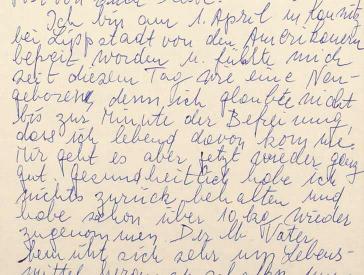

“I was liberated by the Americans on April 1st in Kaunitz near Lippstadt, & since that day, I’ve felt like a newborn, because until the minute of the liberation, I didn’t believe I’d come away alive,”

wrote Irmgard Brill on 21 May 1945 in a letter to her brother Walter, his wife, their children, and others. The Day of Liberation put an end to the unprecedented murder of European Jews, which we call the Holocaust or Shoah today. The Germans persecuted and deported Jewish men, women, and children from all countries that came under their control, and, with the help of collaborators in each country, they systematically murdered between 5.5 and 6.2 million of them.

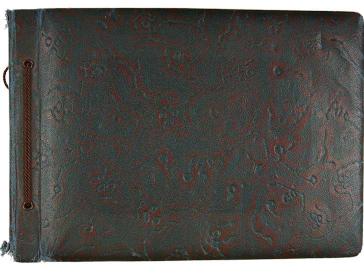

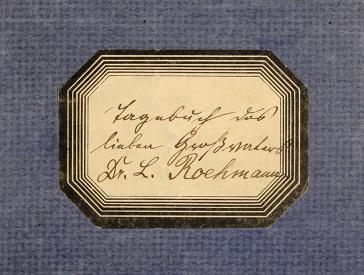

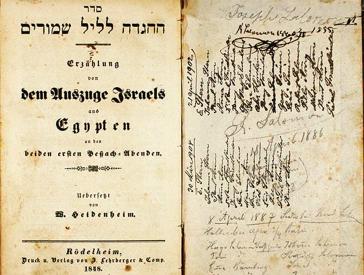

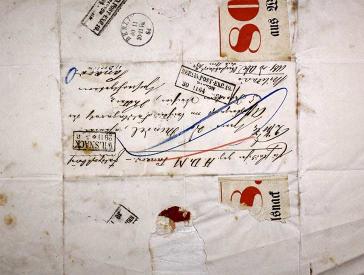

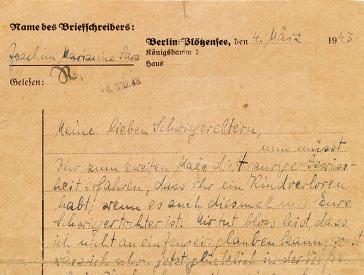

The letter quoted here came into our collection in 2013 through a gift from the writer’s nephew, Ralph Brill (learn more in a post by our curator of photography). It is ten handwritten pages long. Based on the type of paper and the use of a ballpoint pen, the document must be a handwritten copy of the original letter. We therefore cannot rule out the possibility that some words or details were incorrectly transcribed and do not match the original. There are also a number of omissions because several words could not be deciphered during the transcription process. Even so, this later transcript demonstrates that people persecuted by the Nazis who lived through liberation were still not guaranteed survival. Many of them died after the war due to the lasting health impacts of their persecution.

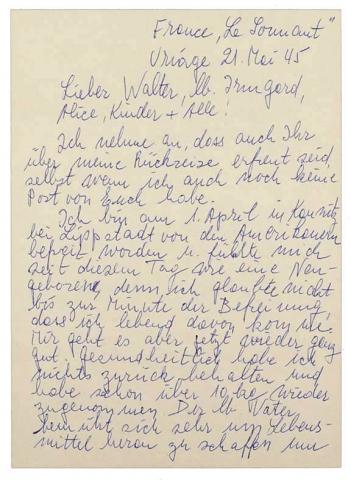

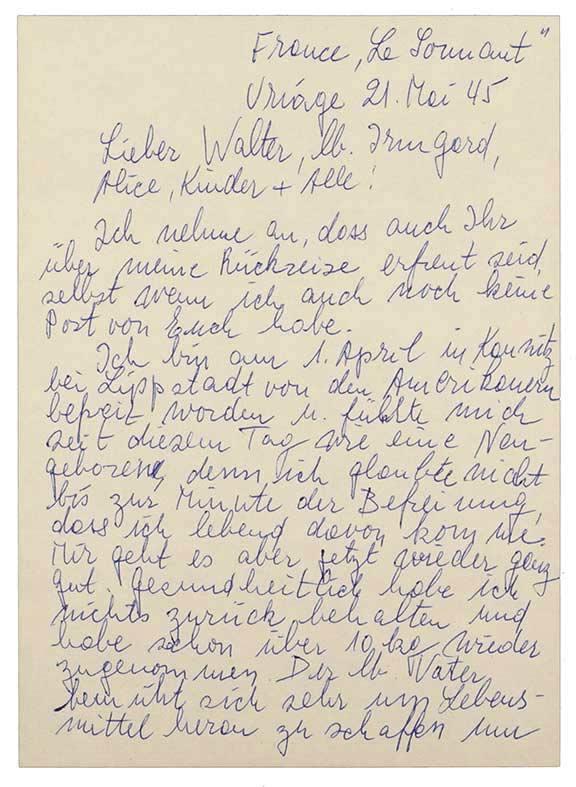

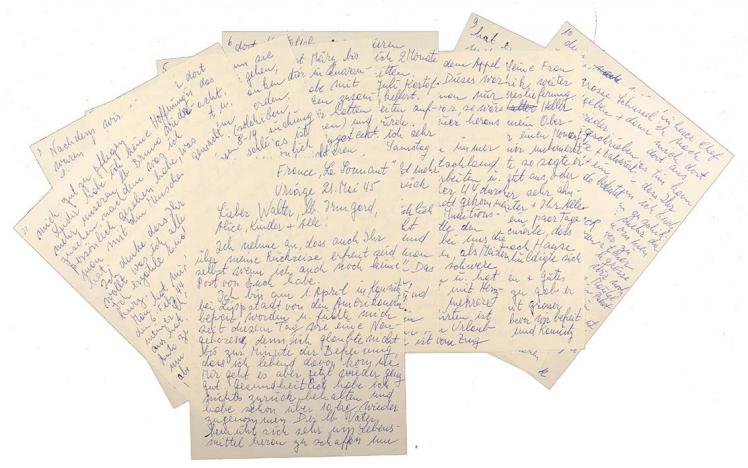

The first page of the handwritten copy of the letter from Irmgard Brill (later Warech, born 1923 in Herzebrock, died 2008 in Paris) to her brother Walter Brill and his family, France, 21 May 1945; Jewish Museum Berlin, accesssion 2013/436/1, gift of Ralph Brill, Brill family archives, photo: Jörg Waßmer

X

X

The first page of the handwritten copy of the letter from Irmgard Brill (later Warech, born 1923 in Herzebrock, died 2008 in Paris) to her brother Walter Brill and his family, France, 21 May 1945; Jewish Museum Berlin, accesssion 2013/436/1, gift of Ralph Brill, Brill family archives, photo: Jörg Waßmer

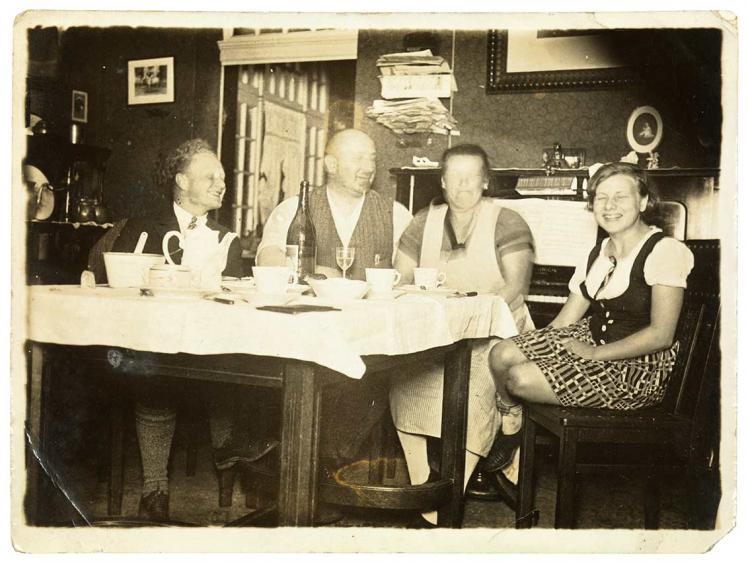

A family meal at the home of Hugo Brill. Irmgard Brill, born 1923, is sitting to the far right. Herzebrock, around 1934; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2013/296/10, gift of Ralph Brill, Brill family archives. Further information on this photograph can be found in our online collections (in German)

In this sense 22-year-old Irmgard was lucky:

“Now I’m doing well again. I’ve not been left with any damage to my health and I’ve already gained back over 10 kg. Dear Father makes a great effort to find food and take good care of me.

Sadly I don’t have any hope of seeing our dear Bruno again, after what I personally saw of what they did with people.”

Indeed, Irmgard and Walter’s brother Bruno was murdered by the Nazis in Sobibor in 1943. The fact that many didn’t survive even after liberation is also a reason why many survivors of 1945 called themselves “the surviving remnant.” While many of them were stranded in Germany and wanted desperately to leave the country as soon as possible, Irmgard Brill wrote her letter from France. On the contrary, she regretted that she couldn’t move back to the German city of her birth:

“Unfortunately after the liberation I couldn’t return to Herzebrock or Rheda, because the French consider me a Frenchwoman. Since we took the train from Münster, I got to see the cemetery where our dear mother [is buried] as well as our house.

Dear Father inquired whether he could return to Germany. As Germans, there’s nothing yet to be done. For the time being, we have to stay here, or I’ll have to look into it myself because my previous bosses have invited me to Paris to recover there, and maybe from there I can do something for dear Father.”

Because the JMB does not have any other documents about Irmgard Brill in its collection to help us interpret this statement, we can only assume that she had good contacts in France and felt more comfortable there than in postwar Germany. Indeed, she died in Paris in 2008. Before she discusses her current situation in France, however, Irmgard first gives a thorough but economical description of her experiences from her detention in February 1944 to her liberation:

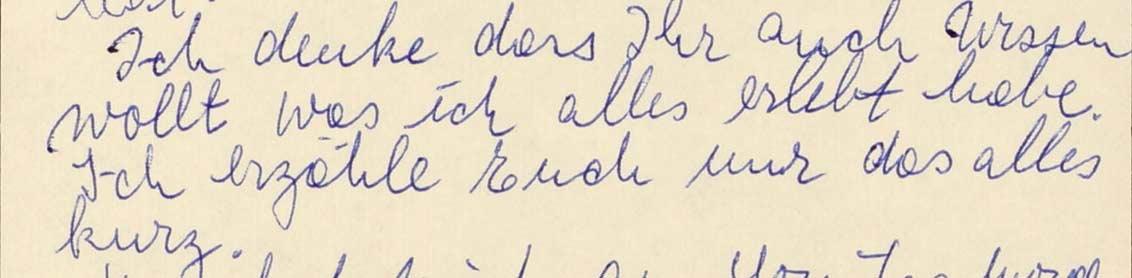

A paragraph from the second page of the copied letter: “I think that you’ll want to know all of the things I’ve been through. I’ll tell you, but briefly.” Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2013/436/1, gift of Ralph Brill, Brill family archives, photo: Jörg Waßmer

“They detained me on Sunday morning, the 6th of Feb. 44 at 8:30 a.m. when I was with my boss. From there they took me in a car to Father's apartment to take him too, but thank God he had a second apartment, and so I could lead them to the one he wasn’t in. From there they brought me to Grenoble where I joined 100 or 120 other detainees.

After we were there for a day, they brought us to the Drancy internment camp. I was there for a month, & from there I was brought with a transport of 1,500 people (a transport like this went about every 8–14 days) to Auschwitz in Upper Silesia, between Katowice & Krakow.

My fate was basically decided upon arrival. To live or die, because when you get out of the cattle car you’re selected & it all depends on luck: out of all of us 1,500 men, women + children, 37 young women + 60 young men were sent into the camp, all of the others into the gas chamber & then the crematorium.”

In fact, Irmgard Brill had arrived in Auschwitz on 10 March 1944 with transport number 69. According to the existing body of research, there were 1501 people on this train, 812 men and 689 women. After the “selection,” 110 men and around 80 women were admitted into the camp – including Irmgard Brill. The other deportees were murdered shortly after their arrival. When Irmgard Brill lists numbers in her letter, we need to keep in mind that these are rough estimates from memory – in addition to the possibility of errors introduced in the transcript. Unlike us today, in May 1945 she was unable to consult other sources and the scholarly literature that would allow her to reconcile her memories with documented statistics. At any rate, her intention here is to describe in general terms the scope of what happened and, most of all, explain how the death camp’s machinery functioned.

It was part of the strategy of annihilation to systematically deceive the victims about their fate, dragging them into the machinery of murder. But for the letter writer, the gas chamber seemed even worse for those who knew what awaited them. She continues:

“They were lucky, they didn’t know where they were going, whereas the weak + sick ones who are picked out from the camp know about everything & stay another 3 days in another barracks after being picked out. That is the worst.”

All ten pages of the copied letter; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2013/436/1, gift of Ralph Brill, Brill family archives, photo: Jörg Waßmer

Next she mainly describes the many coincidences, physical advantages, useful knowledge, personal actions, and meetings with helpful people (including among the perpetrators) that made it possible for her to survive, though she didn’t believe in it until the moment of her liberation:

“In this sense, I personally can’t complain because I didn’t take too many blows, since dear Father told me in advance how you have to behave. Always just keep your eyes open.

Second I didn’t suffer too much from the cold because, thank God, none of my limbs got frostbite Third the fieldwork didn’t make much of a difference to me because I’d often helped father to cultivate the land.

The first month, the month of March until April 10 44 we were in quarantine against typhus. I laid together with several people sick with typhus (that is, we were six to a pallet) and thank God I didn’t catch it. Most people had horrible diarrhea & imagine that we could only use a bucket 2 or 3 times per day, and during that month we could only shower 2x instead of bathing. A shower means quickly undress, under the shower head, quickly dress. No soap, no towel, just 2 minutes of lukewarm water.

After the quarantine I went to the potato bunker. This was one of the best work crews for the initial time because you could get hold of potatoes. Then for 2 months I cut turnips and later until early July I dug + stored potatoes. Then I stopped working because I got sick. For 24 hrs. I had a very high fever & spent Saturday to Tuesday in the sick bay.

When I heard that I wasn’t supposed to come back to the potato bunker, I was overjoyed to go to a knitting mill instead because you weren’t beaten there, light work + sitting the whole day & you could "get hold" of things more easily. That meant you stole aprons, sweaters, or other things and could get about 1 lb. bread for them. Things even went so far that in the evening after roll call we went to the market. That was forbidden, but if you only did what was allowed, no one would have made it through the inferno.

Beginning in the month of June, transports were always going to Germany to work in factories & so by coincidence I went to Lippenstadt in November 44. I worked in a munitions factory there + my foreman was the man who was there with Kürten to inspect the machines. He didn’t give me any hard work & often gave me some bread with beating heart. Many of them knew father. Kürten had an accident when he was at home on vacation. He was run over by a train. His wife took over running the canned food factory. She was an army supplier.

X

X

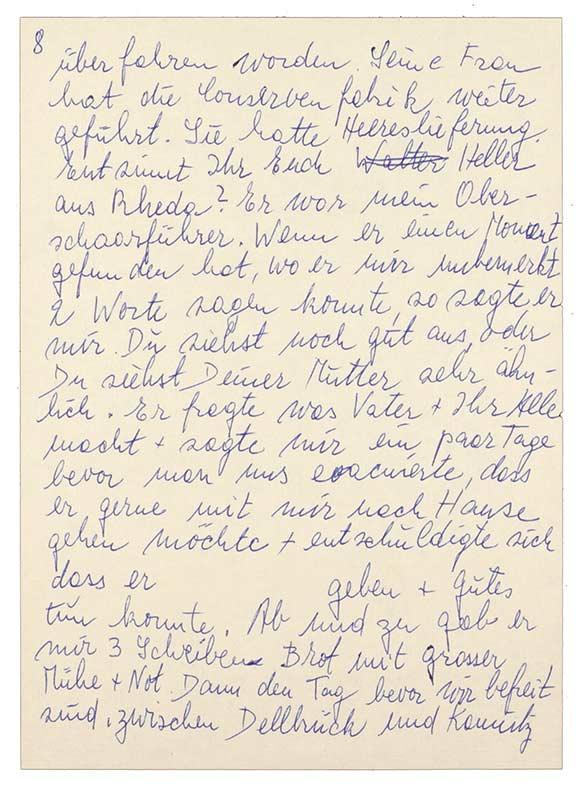

Page 8 of the quoted letter; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2013/436/1, gift of Ralph Brill, Brill family archives, photo: Jörg Waßmer

Do you recall Walter Heller from Rheda? He was my Oberschaarführer [SS squad leader]. Whenever he had a moment when he could say 2 words to me unnoticed, he’d say to me you still look good, or you look a lot like your mother. He asked what Father + you all were doing + said to me a few days before they evacuated us that he’d like to go home with me + apologized that he could give + do good. Now and again he took great pains to give me 3 slices of bread. Then the day before we were liberated, between Dellbrück and Kaunitz he gave me a big bowl of pea soup + then I didn’t see him again.”

When the work camp in Lippstadt had to be evacuated due to approaching American troops, Irmgard was marched on foot with the remaining workers toward the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. As she writes at the beginning of the letter, the group was liberated by the Americans on 1 April 1945 near Kaunitz, Germany.

Arriving at the present in her letter, she adds:

“I didn’t tell you that my head was shaved + I’m tattooed. I have the number 75911 + a triangle underneath it that means Jew on my arm now.”

The male prisoners who were deported to Auschwitz together with Irmgard Brill were assigned the numbers 174,904 to 175,013 upon their registration. The numbers the women were assigned are unknown to researches. At Auschwitz, the numbers were tattooed onto the prisoner’s forearms, sometimes along with a triangle symbol. However, unlike the triangles sewn onto uniforms at other concentration camps, these tattoos were not color-coded. In other words, there was no yellow triangle in the tattoo to designate a person as Jewish.

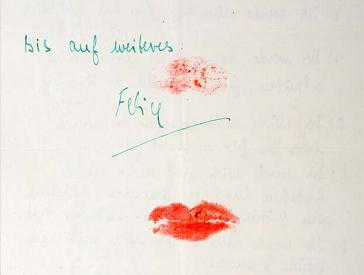

Finally, she asked them

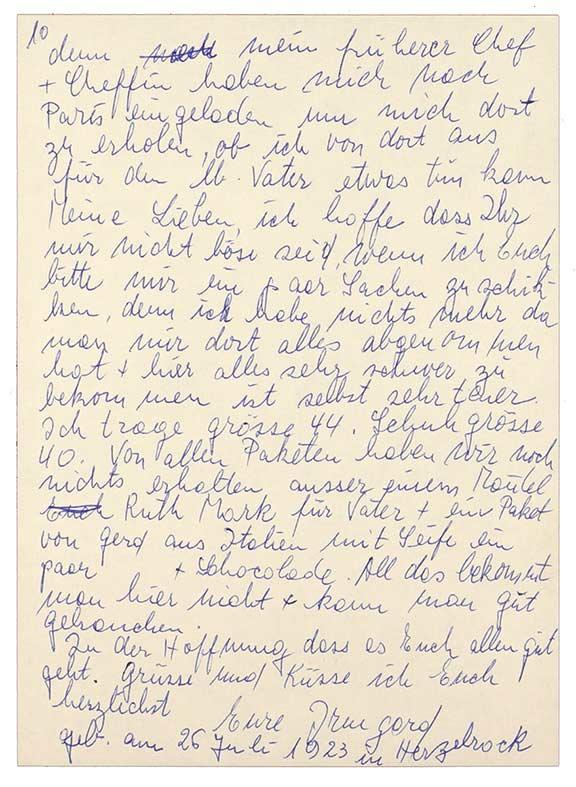

“to send a pair of shoes because I don’t have any since they took everything from me there + everything is very hard to get here even if very expensive. I wear size 44. Shoe size 40. […]

Hoping that you are all doing well. Warm greetings and kisses to you all.

Your Irmgard

Born July 26, 1923 in Herzebrock”

The insertion of a date and place of birth reinforces the status of this document in our collection as a copy. Irmgard Brill is unlikely to have included these details in her letter to her brother. They were probably added when the copy was made.

After reading the entire letter, the feeling of being a newborn mentioned at the beginning of the letter resonates with the exertion that must have been caused by being forced to start completely over again after so many horrible experiences. But for young Irmgard, her will to live and love of life remain in the foreground.

Dr. Mirjam Bitter, digital & publishing research associate

Note: The collection had not yet been fully catalogued when this post was first published on 8 May 2020. We therefore revised it in several places based on additional insights and information gathered during the cataloguing process. For this, we extend our gratitude to our colleague Jörg Waßmer at the JMB Archive. If you are interested in learning more about Irmgard Bril’s life story, you can find an oral history interview with her from 1996 at the Shoah Foundation, titled “Irmgard Warech oral history” (interview code: 8083).

X

X

The last page of the copied letter from Irmgard Brill to her brother and his family; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2013/436/1, gift of Ralph Brill, Brill family archives, photo: Jörg Waßmer

Citation recommendation:

Mirjam Bitter (2020/2024), “Since that day, Iʼve felt like a newborn”. A Striking Document from our Collection about the 1945 Day of Liberation.

URL: www.jmberlin.de/en/node/6979

Behind the Scenes: Anecdotes and Exciting Finds while Working with our Collections (22)