Kindertransporte (Children’s Transports) 1938/39

After the 1938 November Pogrom (Kristallnacht), thousands of Jews tried to leave the German Reich as quickly as possible. But it was unclear who would take them in. Immigration requirements everywhere remained strict, and the waiting lists were long. Some countries declared themselves willing to only take in Jewish children — chief among these countries was Great Britain.

There, a few days after the pogroms in the German Reich, a group of influential Jews and Quakers advocated to British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain to at least take in children temporarily. They promised to provide every child with a guaranteed sum of 50 British pounds, to find housing for the children, and to ensure that they received an education. In this way, the British state sought to ensure that the children would quickly settle in and not become a financial burden on the country.

20,000 children brought to safety

The first Kindertransport, or “children’s transport,” left German territory on 1 December 1938. In this large-scale rescue operation – which continued until the German attack on Poland and the beginning of the Second World War – 10,000 children were brought to safety in Great Britain alone, and another 10,000 children in the Netherlands, Belgium, France, Switzerland, and Sweden.

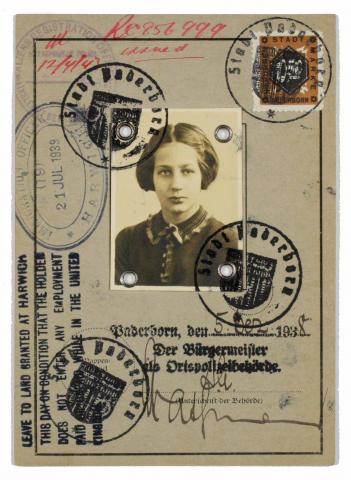

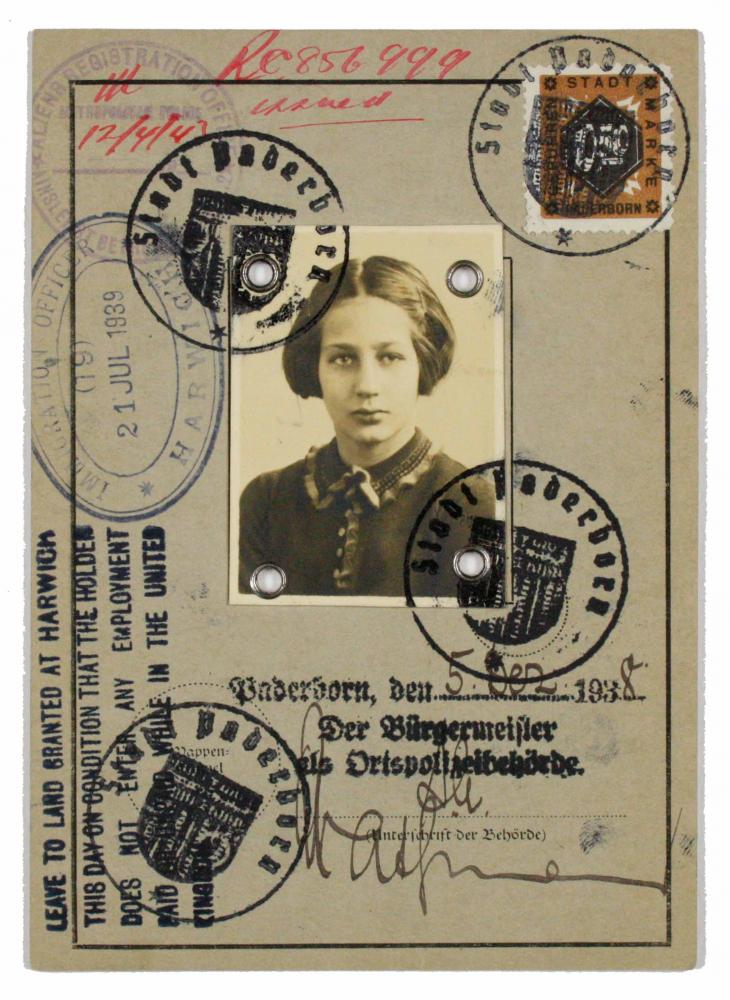

Beate Rose’s childhood passport; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2010/217/93, gift of Beatrice Steinberg. Further information on this document can be found in our online collections (in German)

X

X

Beate Rose’s childhood passport; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2010/217/93, gift of Beatrice Steinberg. Further information on this document can be found in our online collections (in German)

Along with German and Austrian children, Czech Jewish children were also saved by the Kindertransport. Jewish communities and charitable organizations in the German Reich and the receiving countries took care of the immigration requirements, means of travel, and the new accommodations for the children. Great Britain, for example, issued group visas, which allowed the departure to be organized as quickly as possible.

Restrictions on emigration

The National Socialists welcomed the emigration of Jewish children, but they didn’t allow them to take capital out of the country. As such, their parents weren’t able to give them money or jewelry to secure their existence. They were only allowed a single suitcase, a pocketbook, and 10 Reichsmarks.

Beate Rose’s number tag from the Kindertransport rescue mission; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2010/217/99, gift of Beatrice Steinberg. Further information on this object can be found in our online collections (in German)

X

X

Beate Rose’s number tag from the Kindertransport rescue mission; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2010/217/99, gift of Beatrice Steinberg. Further information on this object can be found in our online collections (in German)

Transit and a new home

The children traveled in groups by train and ship, and were accompanied by adults until they arrived in their new country. Some children could live with relatives there who had already emigrated, but most were sent to foster families or group homes. Often they had to perform housework in their foster homes, but they generally were able to continue attending school.

Contact with parents

Gerhard Berliner's stuffed monkey; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2004/46/0, gift of Gert Berliner. Further information on this object can be found in our online collections (in German)

X

X

Gerhard Berliner's stuffed monkey; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2004/46/0, gift of Gert Berliner. Further information on this object can be found in our online collections (in German)

After emigrating, the children could only stay in contact with their parents via letters. When the war broke out, preprinted forms had to be used, which were sent via the Red Cross, and often took a long time to reach the addressee. In many cases, communication was broken off after the beginning of the deportations in fall 1941, and the children received no further news.

The separation of children and parents was traumatic on both sides, but it was often the only possibility to save the children’s lives.

In our collections

In its collections, the Jewish Museum Berlin has preserved documents, photographs, and objects from the Kindertransport. These include letters and postcards from children and their parents, identity cards with which the children left the German Reich, and mementos, such as stuffed animals that accompanied them on the journey.