Access Deferred

Kafka’s Judaism

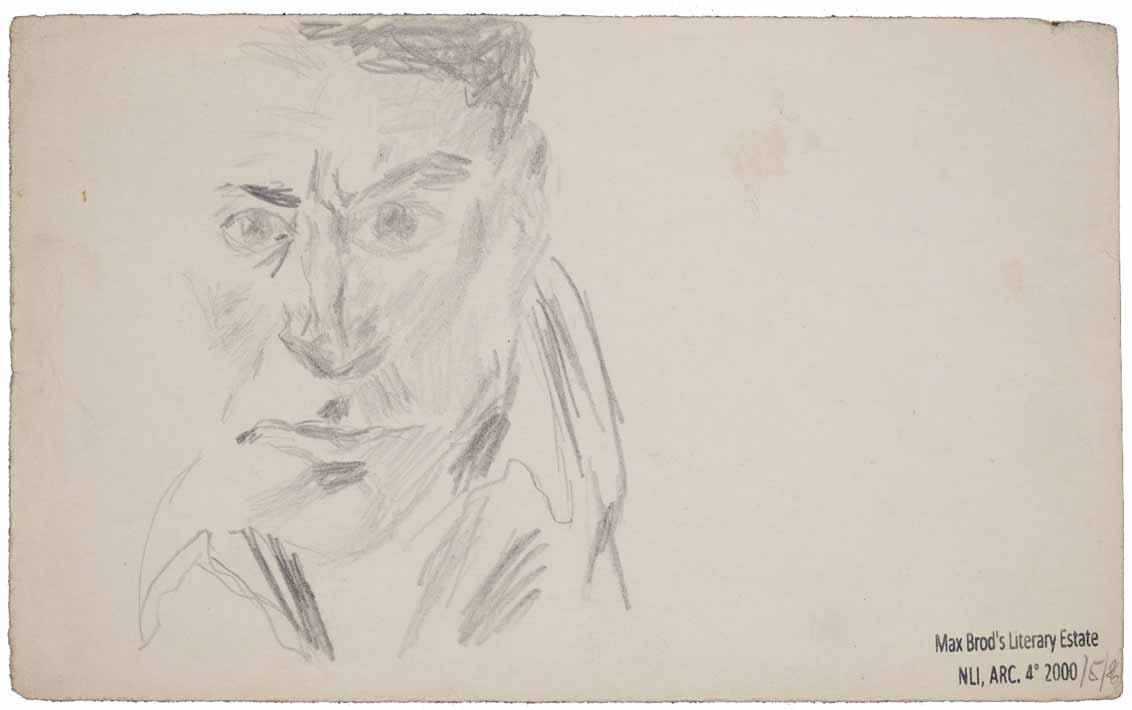

Franz Kafka, self-portrait, [ca. 1911]; סימול ARC. 4* 2000 05 086, Max Brod Archive, National Library of Israel

“It is possible, but not now,”

says the doorkeeper in Before the Law,1 Kafka’s most frequently interpreted prose text, to the man from the country who has arrived at the entrance to the law and asks to be admitted. The man obeys and waits days and years before the gate. There he spends his life in the hope of admission, of knowledge, revelation, justice, or redemption. He spends it in conversation, in waiting and hoping, observing and questioning: he negotiates and curses, asks and bribes, he studies and speculates until the end of his life. The scene of the doorkeeper’s encounter with the man from the country occurs in a place and time that underlie Kafka’s reflections on Jewish existence: it is the place of the threshold and the time of postponement.

The attempts to find an approach to Kafka’s relationship to Judaism are so numerous that it is difficult to make out which entrance provides the most convincing access to its essence. This is as much due to Kafka’s own fluctuating and ambivalent statements about Jews and Judaism as it is to the variety of interpretive approaches that have developed in the more than a century of his reception. The crucial question of Kafka’s relation to Judaism is at the heart of early interpretations of his work, for example those by Max Brod, Felix Weltsch, Margarete Susman, Martin Buber, Walter Benjamin, and Gershom Scholem. It was precisely the opacity and contradiction of Kafka’s remarks about his belonging to the Jewish community, about messianism and Zionism, the Jewish tradition, its rituals and laws, the acculturated way of life of Western Jews, the Eastern Jewish theater, and the Yiddish language that inspired these thinkers’ many interpretations. Despite their very different conceptions of Kafka’s attitude toward Judaism, they all regard him as a visionary of Jewish existence in the modern age.

X

X

Franz Kafka. Black notebook – drawings, ca. 1923; סימול ARC. 4* 2000 05 037, Max Brod Archive, The National Library of Israel

Whereas in the years after the Second World War, Kafka was mostly read in existentialist and universalist terms, scholars and critics writing in the 1980s and 1990s were increasingly interested in his relationship to Judaism, which they mostly conceived in terms of a threshold and an interim period in biographical, historical, and cultural terms. Whether as a paradigmatic Jewish pariah who truly does not belong to any community or as a failing seeker of truth who, like one of his protagonists, sits longingly at the window and waits in vain for the message of the divine emperor, whether as a timid Zionist who, like Moses, will never set foot on the promised land or as a Luftmensch who has lost the foundations of Jewish tradition without having found new ground, Kafka became the epitome of the disoriented city dweller, the quintessential homeless person, the alienated individual in the modern age.

What is striking in the recent reception of Kafka’s writings, however, is not only the increasingly precise biographical and cultural-historical research on Kafka’s Jewish environment in Prague or interpretations that reveal Kabbalistic references in his writings, but also readings that underline his distance from the Jewish religion. One then associates him with heresy, gnosis, marcionism, Paulinism, inverse or negative theology, or “atheology.”2 Kafka’s undeniably idiosyncratic attitude to Judaism is regarded in these interpretations as a rejection of a religion that is seen as legalistic, repressive, and authoritarian. But turning to passages in his texts where he refers explicitly to the Jewish textual tradition and exegesis, the Hebrew Bible and the Talmud, a different picture emerges. There, too, we find hardly any mention of a successful search, a fulfilled hope, or an arrival in the longed-for land—yet the missed, denied, or rejected access does not necessarily prove to be a failure. Rather, it is the idea of a thoroughly Jewish way of life.

This is already laid out in Before the Law. In many respects, the doorkeeper’s answer to the request for admission and the consequences that the man from the country draws from it can be read as a primal scene of Kafka’s relationship to Judaism. As has often been noted, the “man from the country”

is a literal translation of the Hebrew am ha’aretz, the designation for a person who is ignorant of the law. The fact that the am ha’aretz is outside the law because of his ignorance implicitly places him in opposition to the Talmid Chacham, a scholar of the law. However, it is far from clear that the Talmid Chacham would try to enter the law. Perhaps only a person ignorant of the law, an am ha’aretz, can want to enter the law, someone who does not know that in Judaism access to the law does not consist in entry, who does not understand that infinite study in the Talmudic tradition is the encounter with the law itself. A Talmid Chacham would know the Talmudic saying Tzedek, Tzedek Tirdof (“Justice, righteousness, strive for it!”

). The law is to be strived for, but this saying also implies that it cannot be fully attained and fulfilled. There is no final entry.

The Unfulfilled Moment

“I am the end or the beginning.”

3 With these words, Kafka locates himself and his time in a space between the past and the future. As a reversal of Revelation—“I am the Alpha and the Omega, the First and the Last, the Beginning and the End”

(Rev. 22:13)—Kafka’s dictum undermines the claim to totality and the certainty of this Christian creed. His statement, however, is neither a simple reversal nor a negation of it. By replacing the “and” with an “or,” Kafka conveys an uncertainty about his present, and thus implicitly his conception of the present in general as something unfulfilled. He invokes a mode of uncertainty that deprives the end of its finality and the beginning of its foundation. By introducing doubt as an oscillating movement into the interval between end and beginning, the statement sketches a notion of the present that not only subverts all wholeness, but also keeps open the moment on the threshold between past and future.

Søren Kierkegaard, to whom Kafka refers repeatedly in his diary, called the Jews “the most unfortunate of peoples, because they are situated between memory and waiting, namely between two unfulfilled presences.”

4 Kierkegaard’s remark goes back to one of the most fundamental differences between Judaism and Christianity. Whereas Judaism is characterized by the commandment to remember the past and wait for a Messiah who is yet to come, Christianity, for which the Savior has already arrived, harbors the experience of a “fullness of time,”

a moment that once took place and is repeated in every believer. Jewish thought lacks the Christological idea of the pleroma, literally the “fullness,” in which time is fulfilled and, as it were, completed. However, the resulting figure—a postponed, imperfect, and unfinished present—is seen not as the cause of misfortune, but as the possibility of a living care for the world. Although the longed-for, commanded, or strived-for goal remains inaccessible, at its threshold a potential space opens up in which the waiting, questioning, studying, and hoping mode of being of the man from the country unfolds before the law. This mode of being suggests the idea of a human existence that is flawed and unfulfilled, but for that very reason meaningful.

Moses Coming Down from Sinai

On 6 July 1916, Kafka noted laconically in his diary: “Only the Old Testament sees—say nothing yet about it.”

5 Indeed, Kafka will not say much about it, but those of his texts that refer to biblical motifs and figures stage a striking affirmation of the world out of the spirit of Judaism. A fragment from Kafka’s notebooks later known under the title Zum Scheintod (On the Near-Death Experience) vividly shows Kafka evoking a biblical moment in which the culmination of the Jewish conception of origin, Moses’s “encounter” with God on Mount Sinai, is depicted as a threshold experience:

“Whoever has experienced near-death can tell terrifying things about it, but what it is like after death, that he cannot say. He has not even been closer to death than anyone else, he has merely ‘lived’ something extraordinary and this has made his not extraordinary but common life more valuable to him. It is similar for anyone who has lived something extraordinary. Moses, for example, certainly lived something extraordinary on Mount Sinai, but rather than surrendering to this exceptional experience ... , he rushed down the mountain and had valuable things to tell and loved the humans to whom he fled even more than before ... . One can learn much from both the one who returned from near death and the one who returned from Sinai, but one cannot learn what is decisive [das Entscheidende] from them, because they themselves have not experienced it. And if they had experienced it, they would not have come back. But in truth, we don’t even want to know it."6

Kafka draws an analogy between the most terrifying and the most uplifting experience—the confrontation with death and the encounter with God—and reflects on the relationship between these experiences and ordinary life. Paradoxically, both “missed” encounters with the absolute cause the individual to turn to the world instead of surrendering in fear or awe to a beyond. Both experiences lead to an intensification of the relationship to the everyday. Although—or precisely because—neither of the two encounters is fully accessible, those who have experienced them have “valuable things to tell,”

and this telling—stories or texts—and the increased attention to worldly life are implicitly connected. In both cases, Kafka emphasizes the tension between the attraction of an unnameable absolute, which eludes representation, explodes the everyday, and transcends human imagination, and a humanizing impulse directed toward the intelligible and concrete, which affirms the imperfect diversity of the ordinary world. The survivor, who has only almost met death, and Moses, who has only almost met God, return to this world, respectively, from the abyss and the heavenly heights with stories of their experience at the threshold of the other world. Kafka attributes the fruitfulness of these experiences not so much to their proximity to the afterlife as to their significance for ordinary life. The fact that the epiphany—of death or revelation—is not reached and not depicted, and that it even remains uncertain whether an encounter with the beyond has taken place at all, defines the structure of the narrative. In particular, Moses’s encounter with God, of whom in the original story of revelation he sees only the back, confirms the biblical account. What Moses brings back into the world from the threshold to the kingdom of heaven is the Torah as a sign of God’s care for man, as an instruction for life, and as an object of endless study

X

X

Franz Kafka. Black notebook – drawings, ca. 1923; סימול ARC. 4* 2000 05 037, Max Brod Archive, The National Library of Israel

Abraham Before Mount Moriah

An impulse similar to that in Zum Scheintod is expressed in Kafka’s idea of an “other Abraham.” “I could imagine another Abraham.”

7 This first sentence of a letter Kafka wrote to Robert Klopstock in June 1921 is an implicit response to his reading of Kierkegaard’s reflections on the biblical forefather and the sacrifice of Isaac in Fear and Trembling. For Kierkegaard, Abraham is a “knight of faith”

who submits to God.8 Kafka’s idea of a different Abraham refuses this obedience:

“I could think of another Abraham, who—of course he would not make it to the patriarch, not even to the second-hand clothing dealer—who would be ready to fulfill the demand of the sacrifice immediately, willingly like a waiter, but would not be able to make the sacrifice after all because he cannot leave home, he is indispensable, the economy needs him, there is always something else to be arranged, the house is not finished, but without his house being finished, without that support he cannot leave, as the Bible also acknowledges, because it says: “He ordered his house.” […] The next day, I thought a great deal about this Abraham, but they are old stories, no longer worth mentioning; especially not the real Abraham [...]. Not so the above Abrahams, who are standing on their building site and are now suddenly supposed to climb Mount Moriah [...]. So all that remains is the suspicion that these men deliberately do not finish their houses [...] so as not to have to lift [their face] and see the mountain that stands in the distance.”9

Kafka imagines an Abraham who does not go to Mount Moriah to sacrifice his beloved son. Like the biblical patriarch, Kafka’s “other Abraham” is a pious man who could not accomplish the sacrifice. This Abraham, in an imaginary response to God, argues that he “cannot leave home”

because he is needed there. Kafka invents Abraham’s excuses for the fact that he postpones the observance of God’s command, that he can fulfill it only after the completion of his house, “but not now”

: his “other Abrahams,” now in the plural, have become an existential attitude. These Abrahams “are standing on their building site and are now suddenly supposed to climb Mount Moriah.”

An indignant exclamation mark is heard here: the divine decree reaches them in the midst of their care for their house, for their business, for their world, and they are now commanded to give up all that in order to go up the mountain in the service of God and make the sacrifice! As much as Kafka’s “other Abrahams” would have been willing to obey, they are too busy with their “building site” to follow God’s call, and thus defer the sacrificial act. The last sentence of the scene explains this potentially endless postponement. Referring to his other Abrahams who resist the invitation of the call to sacrifice, Kafka speculates: “So all that remains is the suspicion that these men deliberately do not finish their houses [...] so as not to have to lift their face and see the mountain that stands in the distance.”

10

Abraham’s claim that there is always still one more thing to take care of in his house suggests an analogy with Kafka’s own way of writing. Could this house— not a real home, but an infinite building-site—be similar to the Bible and its endless interpretations or, perhaps even more, as Walter Benjamin suggests, to the Talmud? This potentially infinite text, with its meticulous instructions for everyday life and its endless reflections on the organization of the common world, would then offer a place for the homeless to dwell. And maybe even lessen human fear and trembling. For, just like Kafka’s Abraham, endless studying—just like Kafka’s infinite writing—would allow us to avoid what awaits us when we lift our eyes and stare at nothing but the “mountain in the distance,” that terrifying place of martyrdom and sacrifice. It is precisely this understanding of the biblical commandment set out in the Talmud that, contrary to the view of the Apostle Paul, makes humans not miserable, trembling sinners, but world-builders—or, come to that, authors who write unfinished stories and imagine Abrahams who deliberately do not finish their house.

The Tower and the City

Like the texts about Moses’s and Abraham’s failed or avoided visions of God, Kafka’s version of the biblical story of the Tower of Babel in his short text The City Coat of Arms deals with the relationship between transcendence and immanence.11 And as in the other two texts, here the urge to reach the kingdom of heaven is redirected toward the world. The building of the biblical tower is a lofty undertaking in every respect, a striving that signifies elevation to heaven. In the Bible, it fails miserably: the tower is not completed, the city is abandoned, and the project ends in dispersion and fragmentation, marking the true beginning of human history. Most of the time, the biblical text is interpreted to mean that the great project of human unity fails because of divine punishment: God sees the project as hubris or as an attempt to get too close to the divine, to compete with it or replace it, as a rebellion against His commandment to populate the earth and spread over it.

The City Coat of Arms has obvious parallels to the biblical story, but also deviations. In both texts, the tower symbolizes the aspiration to reach heaven. In both, the project fails. But in the Bible, it is God’s punishment that prevents the endeavor’s success, whereas in Kafka’s work, human inaction hinders it. Kafka, it seems, tells his story as an inversion of the original. In the Bible, the construction of the tower is carried out so quickly and impatiently that God puts an end to it. In Kafka’s story, the construction is delayed further and further; the project seems increasingly pointless, and is eventually abandoned and nearly forgotten.

In his rewriting, Kafka turns the biblical story of excessive human ambition into a founding myth for the acceptance of the inevitable limitations and inadequacy of the human endeavor. He transforms the myth of the failed attempt to access heaven through the construction of the tower into an archaeology of human community. Kafka’s builders gradually abandon the construction of the tower, but meanwhile a horizontal structure emerges, the workers’ city. It manifests an imperfect humanity that struggles, quarrels, competes, and fights, but also endures together: The builders are “too attached to each other to leave the city.”

12 They build not a tower, but an imperfect urban community. Access to heaven is replaced by this quarrelsome but intertwined humanity living in the shadows of the incomplete tower. Of course, in the end there is no arrival at the goal, but the story suggests it is precisely abandoning the storming of the sky that holds the city together.

X

X

Franz Kafka. Black notebook – drawings, ca. 1923; סימול ARC. 4* 2000 05 037, Max Brod Archive, The National Library of Israel

The Postponed Messiah

In his 1959 essay "Toward an Understanding of the Messianic Idea in Judaism, Gershom Scholem famously characterizes Jewish existence as “a life lived in deferment, in which nothing can be done definitively, nothing can be irrevocably accomplished.”

13 Whether this is meant as a criticism of the lack of participation by Jews in historical events or as an affirmation of their awareness of an unredeemed humanity is debatable. Scholem traces the mode of deferment back to the messianic idea in Judaism, which longs for redemption as much as it keeps it in check: the supposedly infinite need to prevent the coming of the end is, for Scholem, both the greatness and the “constitutional weakness”

of Jewish messianism.14

Kafka’s “other Abraham” as well as his forgetful tower-builders reinforce this idea, which aligns with the foundations of the Hebrew Bible and its commandment to care for the world. It finds a surprising counterpart in Kafka’s most famous statement on Jewish messianism, the hope of final access to a redeemed world at the end of time: “The Messiah will come only when he is no longer necessary; he will come only on the day after his arrival, he will not come on the last day, but on the very last.”

15 Kafka’s distinction between the last and the very last day is probably only permissible and meaningful as a language game in literature: the last day, which invokes the end of the world including the last judgment, does not seem to be quite the end of things here. It also seems as if Kafka is reflecting on the incompleteness of his writing, which continues more or less blithely after every seemingly final conclusion, after every decision made. It would hardly be surprising if the very last day, after having turned the last day into the penultimate day, were to suffer the same fate—that is, to be only the day before the last one. In this sense, the infinite postponement would not be just a literary game, but would correspond to the “life in deferment” defined by Scholem as the epitome of Jewish existence. With the small difference of literature: because it is only in its performative, thus processual, temporality that the very last can be shifted to the last and then to the penultimate day, on which everything can still happen. Only the unfinished, the uncompleted, with all its expectations and fears, but also its contingency and sense of possibility, can remain open, and not only for the last things, but for the penultimate ones, the ordinary things of imperfect everyday life.

All the texts discussed here seem to invert the biblical source to which they refer, but in the end, they affirm—with slightly different emphases—the worldly dimension that is already inherent in the biblical text. Kafka’s references to Moses, Abraham, the Tower of Babel, and the Messiah are therefore neither heretical, gnostic, nor Pauline. Although they do not remain faithful to the biblical stories literally, they return to their spirit and reveal their underlying worldly orientation. They are not transgressive, as heresies are, nor do they deny the value of worldly existence or attribute the existing evil to a malevolent deity, as a gnostic attitude would. They do not call for the abolition of divine Law, as in Paulinism, and do not declare the absence of God to be the flip side of theism, as in “atheology.” They do not negate, they do not submit, and they do not give up. However, God is not entirely absent from these stories: Moses does not negate his encounter with God; he only turns his attention—and ours—to the people to whom he descends and the stories that he brings. Abraham does not rebel against God’s commandment; he merely indefinitely postpones the act of sacrifice to which he was called for the sake of an unfinished world-building. The non-completion of the tower and human discord are attributed not to the divine punishment of a vengeful god, but to imperfect human dealings with one another. That “we don’t really want to know”

what happened to Moses on Mount Sinai and instead receive his stories from the mountain, that the other Abrahams keep their eyes fixed on the endless construction sites so as not to have to see the holy mountain in the distance, that the builders of Babylon forget their storm on heaven while keeping both its memory and its threat alive in literature, also reflects Kafka’s conception of his own way of relating to the world, his quasi-religious commitment to his writing, which is directed at turning to the world against all odds. The failure to reach the goal, inherent in all the texts discussed here, corresponds to the fundamental view of the Jewish textual tradition that the Bible is “not in heaven” but on earth.16 It indicates a direction, not a result. It does not invite us to access an ultimate truth, but, like Kafka’s man from the country before the law, to enter into a lifelong confrontation with it and everything it stands for.

Vivian Liska is a Professor of German Literature and Director of the Institute for Jewish Studies at the University of Antwerp, Belgium. Since 2013 she is Distinguished Visiting Professor at the Hebrew University, Jerusalem. Her research focuses on modern German literature, literary theory, and German-Jewish thinkers and authors. She is editor of the book series Perspectives on Jewish Texts and Contexts (De Gryuter). Her recent book publications include When Kafka Says We: Uncommon Communities in German-Jewish Literature (Combined Academic Publishers, 2009) and German-Jewish Thought and its Afterlife: A Tenuous Legacy (Indiana University Press, 2016).

This essay can also be found in the catalog accompanying the exhibition ACCESS KAFKA

Citation recommendation:

Vivian Liska (2024), Access Deferred. Kafka’s Judaism.

URL: www.jmberlin.de/en/node/10573

- Franz Kafka, Before the Law, in: A Hunger Artist and Other Stories, a new translation by Joyce Crick, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012, 21.↩︎

- Paul North, The Yield: Kafka’s Atheological Reformation, Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2012. ↩︎

- Franz Kafka, Nachgelassene Schriften und Fragmente II. Schriften, Tagebücher, Briefe, ed. Jost Schillemeit, Frankfurt am Main: S. Fischer, 1992, 98 (my translation). ↩︎

- Maurizio Ferraris, “The Aporia of the Instant in Derrida’s Reading of Husserl,” in: The Moment: Time and Rupture in Modern Thought, ed. Heidrun Friese, Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2001, 34 ↩︎

- Franz Kafka, Diaries, trans. Ross Benjamin, New York: Schocken, 2023, 792. ↩︎

- Kafka, Nachgelassene Schriften und Fragmente II, 141 (my translation). ↩︎

- Franz Kafka to Robert Klopstock, Matliary, June 1921, in: Briefe, 1902– 1924, ed. Max Brod, Frankfurt am Main: S. Fischer, 1980, 333. ↩︎

- Søren Kierkegaard, Fear and Trembling, trans. Howard Hong and Edna Hong, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1983. ↩︎

- Kafka to Klopstock, Briefe, 1902–1924, 333. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Franz Kafka, The City Coat of Arms, trans. Willa and Edwin Muir, in: The Complete Stories, ed. Naum N. Glatzer, New York: Schocken, 1971, 143. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Gershom Scholem, “Toward an Understanding of the Messianic Idea,” trans. Michael A. Meyer, in: The Messianic Idea in Judaism, New York: Schocken, 1971, 1–36, here: 35. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Franz Kafka, Parables and Paradoxes, German and English, New York: Schocken, 1935, 81. ↩︎

- לֹ֥א בַשָּׁמַ֖יִם הִ֑וא (lo ba-shamayim hi), Deuteronomy 30:12. ↩︎

Exhibition ACCESS KAFKA: Features & Programs

- Exhibition Webpage

- Access Kafka (13 Dec 2024 to 4 May 2025): Information on the exhibition chapters, artworks and documents

- Accompanying Events

- Exhibition Opening: 12 Dec 2024, 7 pm

- Curator's Tour with Shelley Harten: Tour with fixed dates, in German

- Access Word – JMB Book Club The Vegetarian by Han Kang: 21 Jan 2025, in German

- Kafka and Art – Lecture by Hans-Gerd Koch: 30 Jan 2025, in German and German Sign Language (DGS)

- Access Word – JMB Book Club A Hunger Artist by Franz Kafka: 25 Feb 2025, in German

- CANCELLED: Access Kafka in the JMB Library: Public tour through our library, 19 Mar 2025, in German

- Access Space – Night Walk with Artist Alona Rodeh: 20 Mar & 10 Apr 2025

- Access Judaism – Kafka & Visuality and Judaism: 1 Apr 2025, in German

- The Happy End of Access Kafka! A Sunday with Kafka and Kippenberger to mark the final week of the exhibition, 27 Apr 2025, in German

- On Fathers. Writing workshop with brunch and guided tour: Event with fixed dates

- Public Tour in German: Tour with fixed dates

- Public Tour in English: Tour with fixed dates

- Public Tour in Hebrew: Tour with fixed dates

- Bookable Tour for Groups: Tour by appointment

- Bookable Workshop for Students: Workshop by appointment, in German

- Digital Content

- Current page: Access Deferred: Essay by Vivian Liska on Kafka’s Judaism, from the exhibition catalog, 2024

- Franz Kafka: A short biography and further online content on the topic

- Kafka in Berlin: Berlin walk on Jewish Places to biographical stations of Franz Kafka, written by Hans-Gerd Koch

- Publications

- Exhibition catalog: German edition, 2024

- Exhibition catalog: English edition, 2024