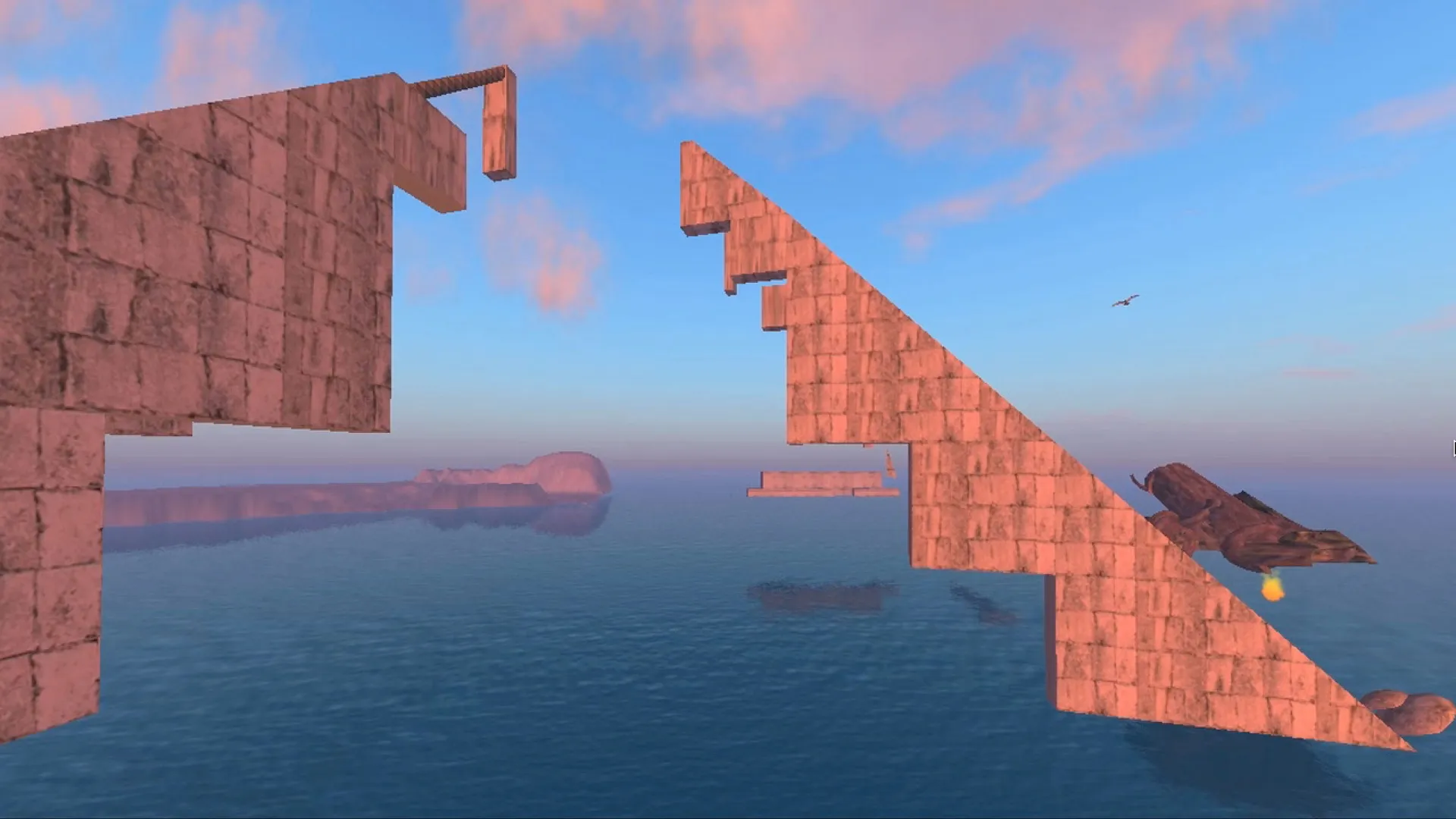

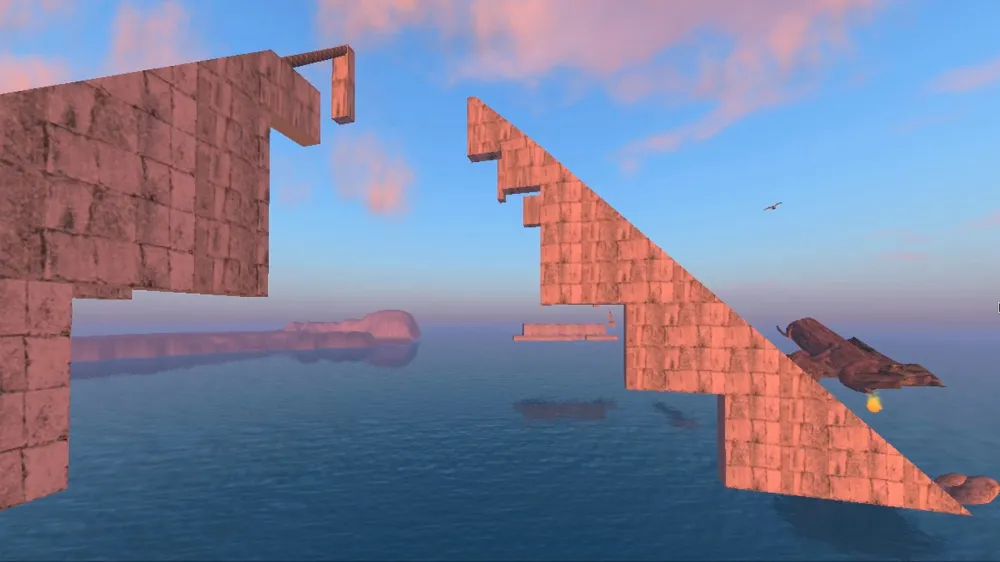

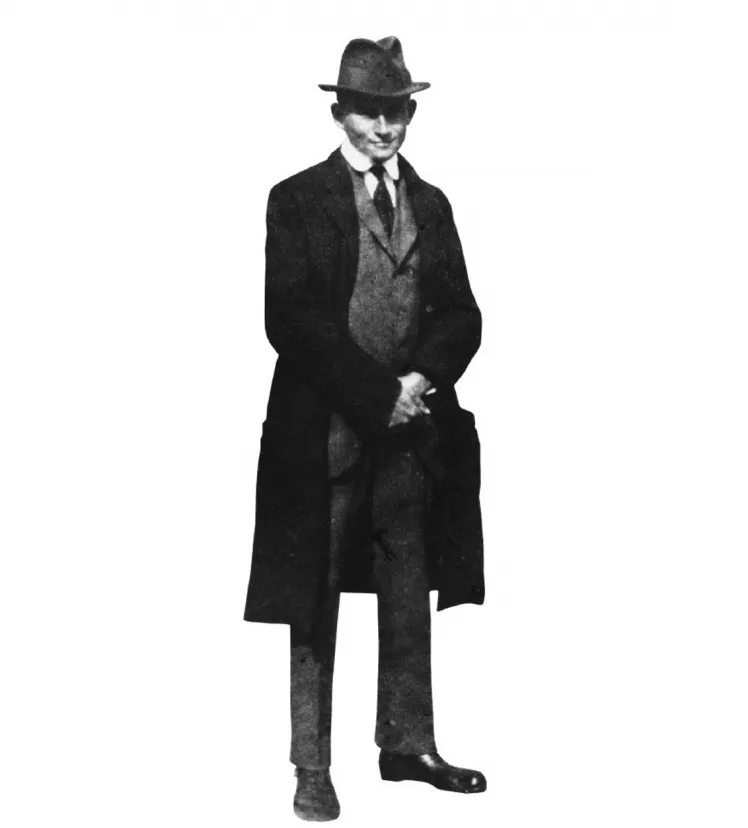

Mary Flanagan, [borders: chichen itza], 2010

Access Kafka

Exhibition

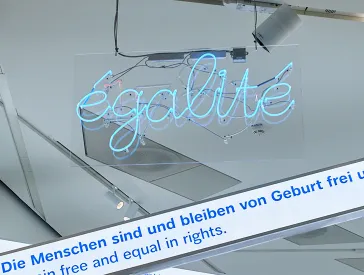

Kafka comes to Berlin! One hundred years after the death of Franz Kafka, the Jewish Museum Berlin is providing new insights into his work with its exhibition Access Kafka: manuscripts and drawings from Franz Kafka’s estate come together with contemporary art by artists such as Yael Bartana, Maria Eichhorn, Anne Imhof, Martin Kippenberger, Maria Lassnig, Trevor Paglen and Hito Steyerl. The focus is on universal and timeless questions concerning access.

Past exhibition

Where

Old Building, level 1

Lindenstraße 9–14, 10969 Berlin

In its broadest sense, the term “access” refers to the permission, freedom and ability to enter or leave a place – including an imaginary or virtual space. Questions of admission and affiliation are a recurring motif in Kafka’s literary texts. His unsettling descriptions of disorientation, surveillance and meaningless rules are relevant in a different way today than they were in Kafka’s era: the boundaries between private and public spheres are blurring in our age of widespread digitization, in which social networks, artificial intelligence and algorithms control access anonymously. These circumstances define the conditions for social participation. The contemporary artworks reflect these questions, also with reference to the role of art and artistry itself. The exhibition Access Kafka and accompanying program invite you to follow, participate in and further develop these reflections.

Artists: Cory Arcangel, Yuval Barel, Yael Bartana, Guy Ben-Ner, Marcel Broodthaers, Marcel Duchamp, Maria Eichhorn, Mary Flanagan, Ceal Floyer, Lynn Hershman Leeson, Tehching Hsieh, Anne Imhof, Fatoş İrwen, Uri Katzenstein, Lina Kim, Martin Kippenberger, Maria Lassnig, Michal Naaman, Trevor Paglen, Alona Rodeh, Roee Rosen, Gregor Schneider, Hito Steyerl

Find out more about the exhibition chapters on this page:

Exhibition Booklet

Download (PDF / 261.67 KB / in English and German / accessible)Access Denied

The refusal of access is everywhere in our society, whether economically, politically, or in private life. In his texts, Kafka – a legal scholar by training – gives tangible shape to that refusal. Josef K. is under threat of a trial without knowing why and by whom; Gregor Samsa, transformed into a kind of “vermin,” is shut out by his family; the man from the country waits in vain “Before the Law” for admission. Kafka himself nearly prevented the almost unrestricted access to his own works that we enjoy today: he instructed that all his manuscripts must be destroyed after his death. Despite the perceived accessibility of art, Kafka’s biography and texts show it is never certain when something becomes art, when somebody becomes an artist – or who decides. Is it the artists themselves? The public? Or the job market?

X

X

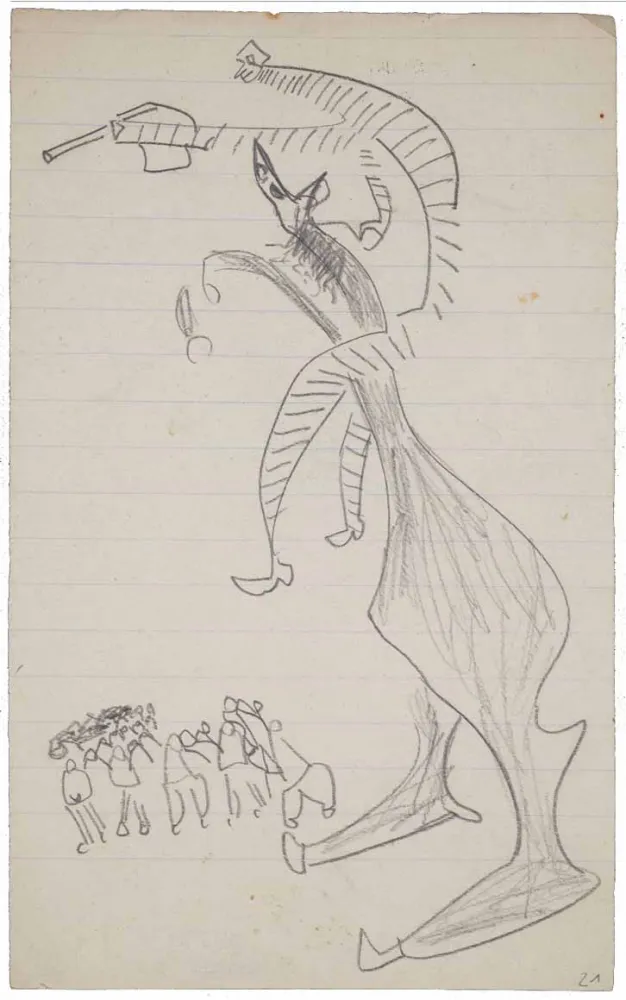

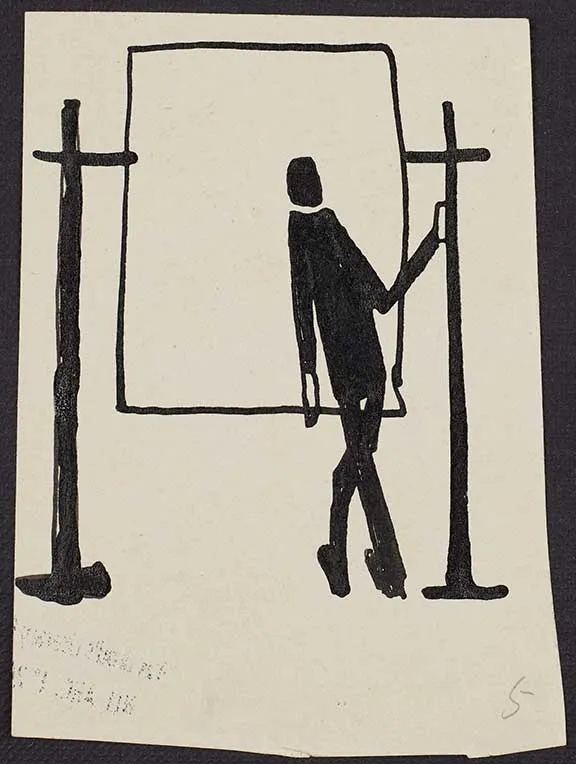

Franz Kafka, drawing, [ca. 1923]; סימול ARC. 4* 2000 05 037, Max Brod Archive, National Library of Israel

Artworks in the Exhibition Room Access Denied

An English translation of “The Great Theatre of Oklahama” can be found in: The Man Who Disappeared (America), a new translation by Ritchie Robertson, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012

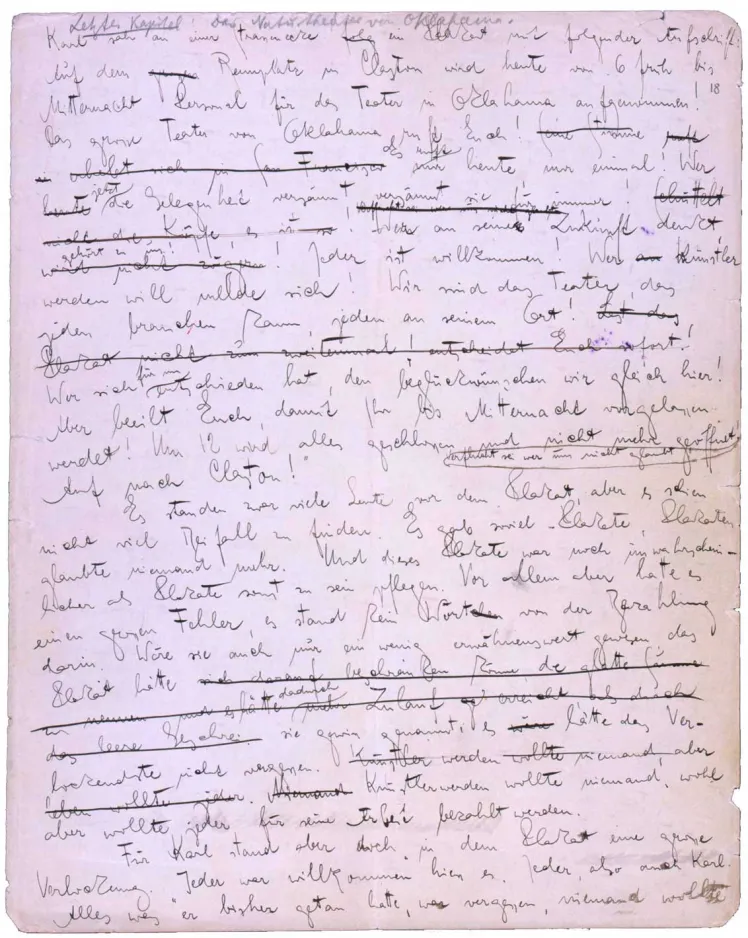

Franz Kafka: Das Naturtheater von Oklahoma, 1914

Karl sah an einer Straßenecke ein Plakat mit folgender Aufschrift: „Auf dem Rennplatz in Clayton wird heute von sechs Uhr früh bis Mitternacht Personal für das Theater in Oklahama aufgenommen! Das große Theater von Oklahama ruft euch! Es ruft nur heute, nur einmal! Wer jetzt die Gelegenheit versäumt, versäumt sie für immer! Wer an seine Zukunft denkt, gehört zu uns! Jeder ist willkommen! Wer Künstler werden will, melde sich! Wir sind das Theater, das jeden brauchen kann, jeden an seinem Ort! Wer sich für uns entschieden hat, den beglückwünschen wir gleich hier! Aber beeilt euch, damit Ihr bis Mitternacht vorgelassen werdet! Um zwölf Uhr wird alles geschlossen und nicht mehr geöffnet! Verflucht sei, wer uns nicht glaubt! Auf nach Clayton!“

Es standen zwar viele Leute vor dem Plakat, aber es schien nicht viel Beifall zu finden. Es gab so viel Plakate, Plakaten glaubte niemand mehr. Und dieses Plakat war noch unwahrscheinlicher, als Plakate sonst zu sein pflegen. Vor allem aber hatte es einen großen Fehler, es stand kein Wort von der Bezahlung darin. Wäre sie auch nur ein wenig erwähnenswert gewesen, das Plakat hätte sie gewiss genannt; es hätte das Verlockendste nicht vergessen. Künstler werden wollte niemand, wohl aber wollte jeder für seine Arbeit bezahlt werden.

Für Karl stand aber doch in dem Plakat eine große Verlockung. „Jeder war willkommen“, hieß es. Jeder, also auch Karl. Alles, was er bisher getan hatte, war vergessen, niemand wollte ihm daraus einen Vorwurf machen. Er durfte sich zu einer Arbeit melden, die keine Schande war, zu der man vielmehr öffentlich einladen konnte!

Und ebenso öffentlich wurde das Versprechen gegeben, dass man auch ihn annehmen würde. Er verlangte nichts Besseres, er wollte endlich den Anfang einer anständigen Laufbahn finden, und hier zeigte er sich vielleicht. Mochte alles Großsprecherische, was auf dem Plakate stand, eine Lüge sein, mochte das große Theater von Oklahama ein kleiner Wanderzirkus sein, es wollte Leute aufnehmen, das war genügend. Karl las das Plakat nicht zum zweiten Male, suchte aber noch einmal den Satz: „Jeder ist willkommen“ hervor.

Franz Kafka

Der Verschollene (Amerika) (The Man Who Disappeared (America)), 1914

Excerpt from the presumed final chapter “The Great Theatre of Oklahama” of the unfinished novel

Picture: Detail from the book cover of Franz Kafka: Amerika. Roman, München: Kurt Wolff Verlag, 1927.

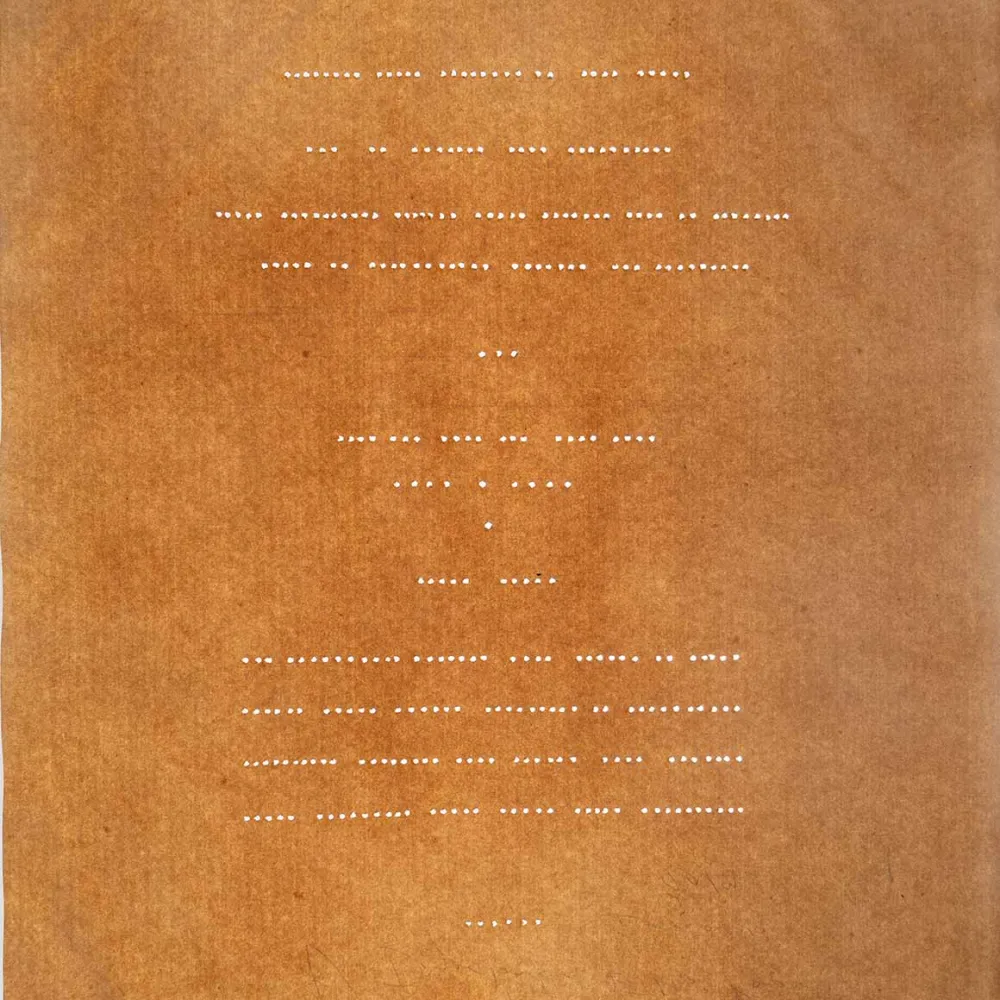

Fatoş İrwen, The Other History: Read, 2019–2020, Paper and pinholes, 21 x 29,7 cm each, and Hevsel, 2022, Ink on paper, red thread, two drawings, 37 x 78,5 cm each; courtesy the artist and Zilberman Instanbul, Berlin, Miami

In one of his fragments Kafka writes about a “ride of dreams,” describing a liberating act that can be linked to Fatoş İrwen’s artistic practice. A Kurdish artist, İrwen created the works shown here while serving a sentence as a political prisoner in Diyarbakır from 2017 to 2020. While incarcerated, she used art to express resistance and document all that could not be said.

Her Hevsel series calls to mind Rorschach inkblots, the interpretation of which reveals more about the psychology of the interpreter than that of the creator. The artist’s ink landscapes, seemingly born of her memories and desires, transcend the prison walls.

The perforated paper in The Other History: Read mimics a text that seems offcial but exists only in the artist’s imagination. Suspecting that the holes represented a secret code, the prison guards grew wary and imposed sanctions on the artist.

The following image was only allowed to be shown here during the exhibition period: Ceal Floyer, No Positions Available, 2007, installation, signs on Wall; courtesy the artist and Esther Schipper, Berlin/Paris/Seoul; VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2024, Foto: Nick Ash

For this large-scale wall installation, Ceal Floyer used signs that are commonly seen in shop windows in North America to advertise job vacancies. When they are no longer needed, they can be turned around, hiding the hopeful “Help Wanted” message on the other side. In the exhibition, provides a contrast to the inviting series of posters recruiting workers for the Theater of Oklahoma in Kafka’s novel The Man Who Disappeared (America). These advertisements read “Everyone is welcome! If you want to be an artist, come along!” Floyer’s signs are crammed together to fll the entire wall and literally leave “no position” between them. The artist transfers the signs’ constantly repeated exclusionary message to the exhibition space, emphasizing its cruelty.

The following image was only allowed to be shown here during the exhibition period: Hito Steyerl, Strike, 2010, Single channel high-defnition digital video, sound, fat screen mounted on two poles, 28 sec., staff: Christoph Manz; CC 4.0 Hito Steyerl, courtesy the artist and Andrew Kreps Gallery, New York; VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2024

The English word “strike” can mean two different things: a strategic work stoppage by employees and a physical blow. In this short video, the artist strikes a fat screen with a hammer and chisel, revealing the outline of its matrix and rendering the monitor unusable for conventional purposes. In Strike, Steyerl uses traditional sculpting tools to deny people access to the consumer-oriented world of media images while at the same time creating a media sculpture herself.

The following image was only allowed to be shown here during the exhibition period: Martin Kippenberger, Untitled, 1991, wood, lacquer, metal, fabric, faux leather, foam rubber, adhesive tape, aluminium, plastic, motor; © Estate of Martin Kippenberger, Galerie Gisela Capitain, Köln, photo: Jens Ziehe

In his works Martin Kippenberger constantly questions the concept of art and his own role as an artist. In this context, the theme of the merry-go-round is highly referential: the colorful rails resemble a palette on which the artist literally goes round in circles. The ejector seat holds out the hope of escape, but the fairy wings attached to it signal that any attempt is doomed to failure. As a metaphor for the life of an artist, this work navigates the poles of security and insecurity, selfdetermination and external control, and fun and misfortune.

Kippenberger incorporated a variation of the carousel into his epic installation The Happy End of Franz Kafka’s ‘Amerika,’ which references Kafka’s unfnished novel . Numerous offce settings are arranged on a sports feld, suggesting a variety of encounters that Kafka’s protagonist Karl—an immigrant to America—might have at the end of the novel. A detailed view of one version of this installation can be accessed at kippenberger.museum-folkwang.de.

Kafka’s Last Will

Franz Kafka died on June 3, 1924, when aged only 40. Kafka almost denied future generations access to his largely unpublished estate. Find out more from this note in his will:

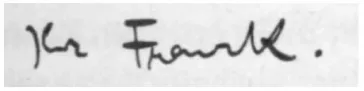

Max Brod (1884-1968), author, literary and art critic, met Kafka as students in Prague in 1902 and became a very close friend. He encouraged Kafka to write and helped him publish his texts. Today he is best known as the editor of Kafka’s estate.

Max Brod, 1914, Dresden; German Literature Archive Marbach

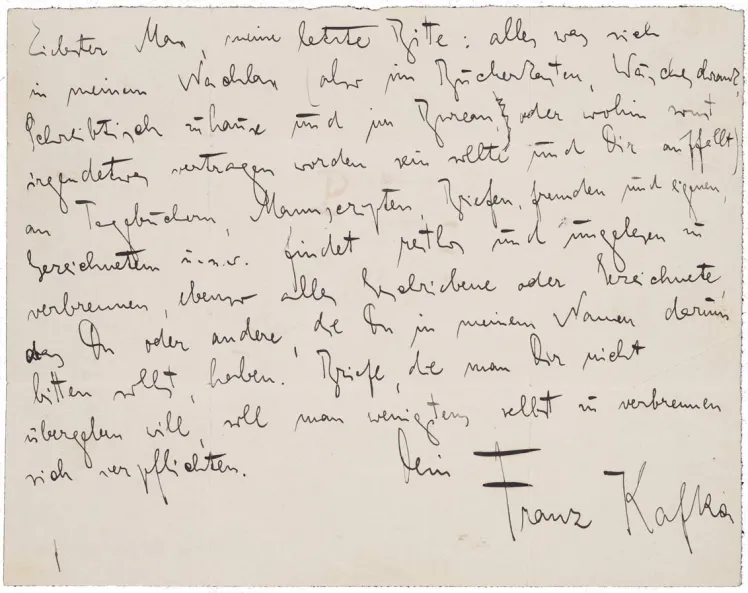

In 1921/22, Kafka left Max Brod two testamentary notes with instructions to completely destroy his estate.

Today, the majority of Kafka’s estate is located here:

- National Library of Israel, Jerusalem

- Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford

- German Literature Archive Marbach

Max Brod ignored this instruction to burn everything unread! This is fortunate—otherwise we would only have access to previously published texts by Kafka. No Castle, no Process!

In 1939 Brod got on the very last train out of Prague as the Germans marched into the Czech Republic, in his luggage Kafka’s manuscripts e.g. the last will.

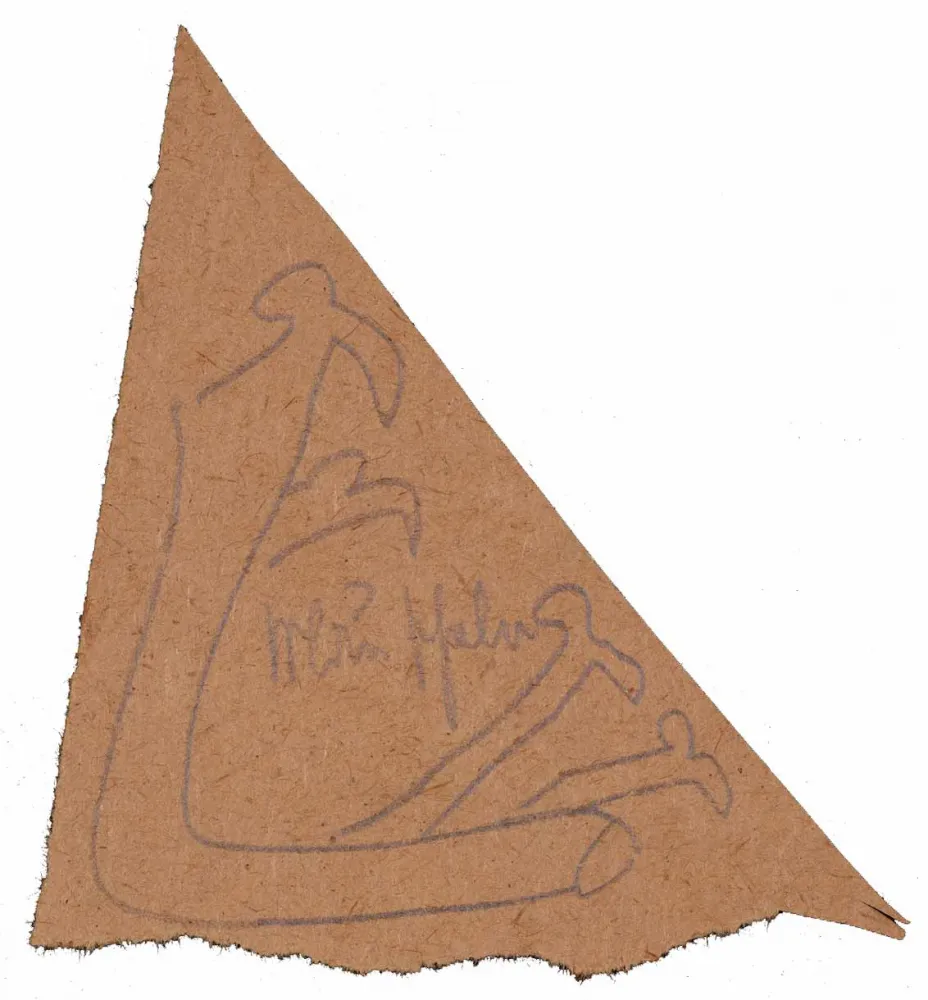

Max Brod cut out this and other drawings to illustrate the Kafka editions.

Figure from a sketch book, from about 1901–7 or later; סימול ARC. 4* 2000 05 037, Max Brod Archiv, National Library of Israel

Did Kafka really want everything to be burned? Would he then have addressed his will to Max Brod?

Testamentary note to Max Brod, from: Franz Kafka’s testaments, 1921-1922; סימול ARC. 4* 2000 05 050 Max Brod Archive, National Library of Israel

Transcription of the testamentary note to Max Brod (1921/22)

“Dearest Max, my last request: Everything I leave behind me (in my bookcase, linen cupboard, my desk both at home and in the office, or anywhere else where anything may have got to and meets your eye) in the way of diaries, manuscripts, letters (my own and others’), sketches and so on, is to be burned unread and to the last page, as well as all writings of mine or sketches which either you may have or other people, from whom you are to beg them in my name. Letters which are not handed over to you should at least be faithfully burned by those who have them.

Yours

Franz Kafka”

Benjamin Balint, Kafka’s Last Trial, The Case of a Literary Legacy, New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 2018.

Kafka’s Work

Franz Kafka was a lawyer by profession. His vocation was literature. He described both as work.

The following manuscript page from the unfinished novel The Man Who Disappeared (America), written in 1914, gives an insight into his work. It is the first page of the presumed final chapter about the protagonist Karl Rossmann's encounters with the Theater of Oklahoma.

Kafka’s novel is about the young Karl Rossmann, who emigrates to America. There he is disowned by his rich uncle and is forced to seek his fortune in the labor market.

The Nature Theater of Oklahoma is looking for artists. Karl Rossmann applies and ends up getting a job as a “technical worker” due to his lack of official documents.

handwritten addition by Max Brod:

“Last chapter: The Natural Theater of Oklahama.”

Kafka was inspired by Arthur Holitscher's travelogue America. Today and Tomorrow, 1912. Kafka copied the spelling mistake “Oklahama” from Holitscher.

Arthur Holitscher (1869–1941) was a Hungarian-Jewish author of travel books. As a socialist, he wrote about the labor market and social injustice in America.

“If you want to be an artist, come along!”

Franz Kafka raises his hand.

“No one wants to be an artist, but everyone wants to be paid for their work.” – Kafka shows solidarity with the working class.

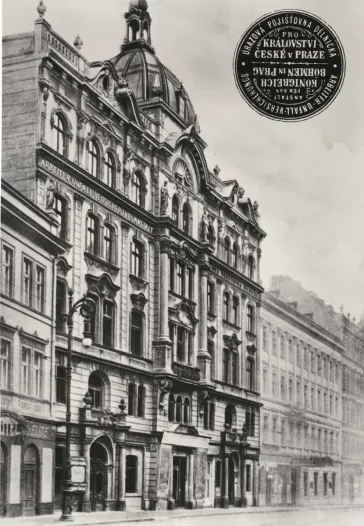

From 1908 to 1922, Kafka worked as a civil servant at the Workers’ Accident Insurance Institute in Prague.

Workers’ Accident Insurance Institute in Prague; akg-images / Archiv K. Wagenbach

First page of the presumed final chapter “The Great Theatre of Oklahama” of the unfinished novel Der Verschollene (Amerika) (The Man Who Disappeared (America)), 1914, ink and pencil on paper, 25 × 20.5 cm; MS. Kafka 42, fol. 18r, Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford

Transcription of the page above: Naturtheater von Oklahoma (in German)

Karl sah an einer Straßenecke ein Plakat mit folgender Aufschrift: „Auf dem Rennplatz in Clayton wird heute von sechs Uhr früh bis Mitternacht Personal für das Theater in Oklahama aufgenommen! Das große Theater von Oklahama ruft euch! Es ruft nur heute, nur einmal! Wer jetzt die Gelegenheit versäumt, versäumt sie für immer! Wer an seine Zukunft denkt, gehört zu uns! Jeder ist willkommen! Wer Künstler werden will, melde sich! Wir sind das Theater, das jeden brauchen kann, jeden an seinem Ort! Wer sich für uns entschieden hat, den beglückwünschen wir gleich hier! Aber beeilt euch, damit Ihr bis Mitternacht vorgelassen werdet! Um zwölf Uhr wird alles geschlossen und nicht mehr geöffnet! Verflucht sei, wer uns nicht glaubt! Auf nach Clayton!“

Es standen zwar viele Leute vor dem Plakat, aber es schien nicht viel Beifall zu finden. Es gab so viel Plakate, Plakaten glaubte niemand mehr. Und dieses Plakat war noch unwahrscheinlicher, als Plakate sonst zu sein pflegen. Vor allem aber hatte es einen großen Fehler, es stand kein Wort von der Bezahlung darin. Wäre sie auch nur ein wenig erwähnenswert gewesen, das Plakat hätte sie gewiss genannt; es hätte das Verlockendste nicht vergessen. Künstler werden wollte niemand, wohl aber wollte jeder für seine Arbeit bezahlt werden.

Für Karl stand aber doch in dem Plakat eine große Verlockung. „Jeder war willkommen“, hieß es. Jeder, also auch Karl. Alles, was er bisher getan hatte, war vergessen, niemand wollte [ihm daraus einen Vorwurf machen.]

Franz Kafka: Der Verschollene (Amerika) (The Man Who Disappeared (America)), 1914 First page of the presumed final chapter “The Great Theatre of Oklahama” of the unfinished novel

Access Word

In present-day communication forms, access is defined by symbols, slogans, codes, and emojis, and script is replaced by pictograms. Words become pictures. Kafka chooses writing and the text as his route to access the world of his imagination – a transit that demands his great concentration. His imagery often involves doors and windows, giving a visible form to experiences of exclusion and intrusion. It is rare for Kafka to describe the external appearance of his protagonists or the setting in his stories. He forbade all illustration of his works, and his own drawings are condensed like symbols. The author concentrates on the essence, leaving embellishments to his readers’ imagination.

X

X

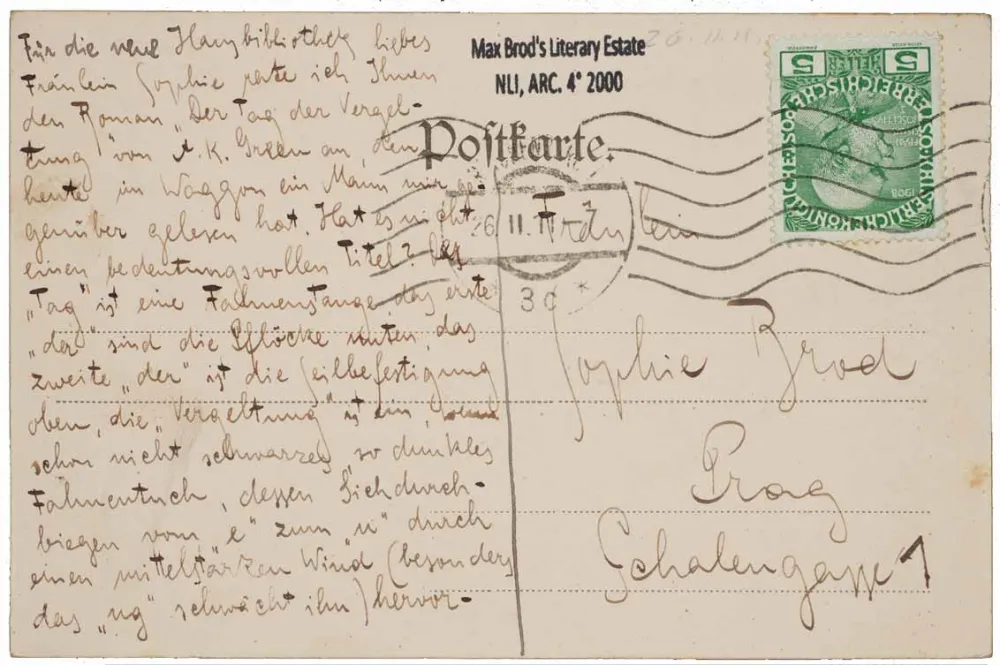

Franz Kafka, postcard to Sophie Brod, 26.2.1911, pencil on printed cardboard, 9.3 × 14.1 cm; סימול ARC. 4* 2000 05 044, Max Brod Archive, National Library Israel

Artworks in the Exhibition Room Access Word

An English translation of “A Little Woman” can be found in: Franz Kafka, A Hunger Artist and Other Stories, a new translation by Joyce Crick, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

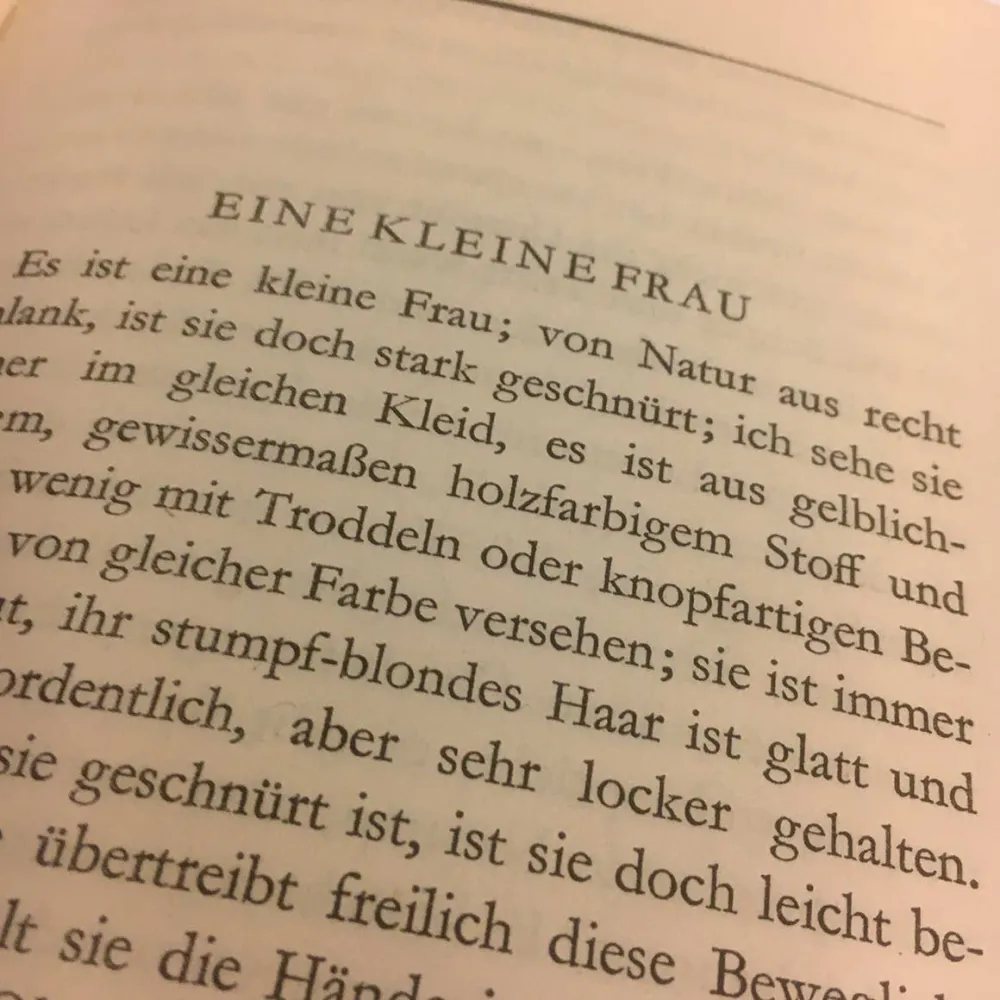

Franz Kafka: Eine kleine Frau, 1924

Es ist eine kleine Frau; von Natur aus recht schlank, ist sie doch stark geschnürt; ich sehe sie immer im gleichen Kleid, es ist aus gelblich-grauem, gewissermaßen holzfarbigem Stoff und ist ein wenig mit Troddeln oder knopfartigen Behängen von gleicher Farbe versehen; sie ist immer ohne Hut, ihr stumpf-blondes Haar ist glatt und nicht unordentlich, aber sehr locker gehalten. Trotzdem sie geschnürt ist, ist sie doch leicht beweglich, sie übertreibt freilich diese Beweglichkeit, gern hält sie die Hände in den Hüften und wendet den Oberkörper mit einem Wurf überraschend schnell seitlich. Den Eindruck, den ihre Hand auf mich macht, kann ich nur wiedergeben, wenn ich sage, dass ich noch keine Hand gesehen habe, bei der die einzelnen Finger derart scharf voneinander abgegrenzt wären, wie bei der ihren; doch hat ihre Hand keineswegs irgendeine anatomische Merkwürdigkeit, es ist eine völlig normale Hand. Diese kleine Frau nun ist mit mir sehr unzufrieden, immer hat sie etwas an mir auszusetzen, immer geschieht ihr Unrecht von mir, ich ärgere sie auf Schritt und Tritt; wenn man das Leben in allerkleinste Teile teilen und jedes Teilchen gesondert beurteilen könnte, wäre gewiß jedes Teilchen meines Lebens für sie ein Ärgernis.

Beginning of the story “Eine kleine Frau”, in: Franz Kafka, Die Erzählungen, Frankfurt a. M.: S. Fischer Verlag, 2024, p. 464–474

Picture: Page of the book Franz Kafka: Ein Hungerkünstler. Vier Geschichten. Berlin: Verlag Die Schmiede, 1924

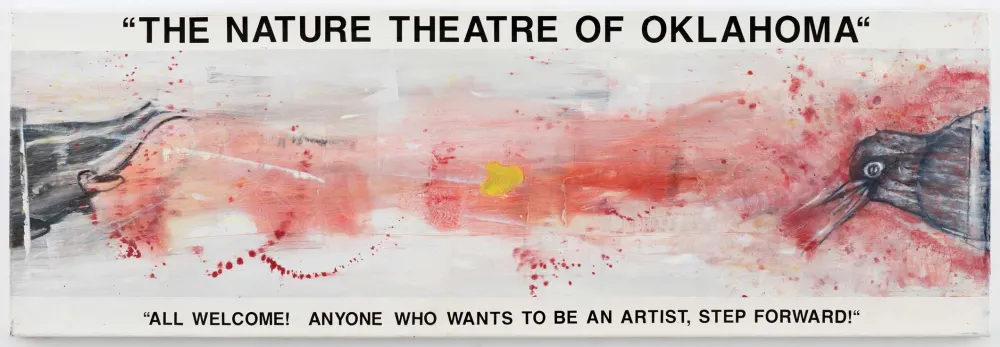

Michal Naaman, All Welcome!, 2021, oil and letraset on canvas, 50 x 150 cm; courtesy the artist and G Gordon Gallery

Michal Naaman’s intense engagement with Kafka is based on her interest in the relationship between words and images. Texts and symbols, which she adopts from cultural and art history, appear either pieced together and pulled apart in her paintings. They raise questions about what is visible and what is hidden.

In her series on the Nature Theater of Oklahoma in Kafka’s unfnished novel The Man Who Disappeared, Naaman follows the call “Anyone who wants to be an artist, step forward!” She quotes passages from the novel in English and Hebrew and presents symbols and words ranging from the meaningful (Wittgenstein’s “rabbit-duck” illusion) to the meaningless (BIM BAM BOM).

The large-format painting is part of a series devoted to the fnal words of famous fgures. The words thought to be Kafka’s last—spoken to his friend, the doctor Robert Klopstock—appear at the center of the canvas. The ambiguous statement “Kill me, or you are a murderer” is surrounded by diamonds formed by masking tape. The artist uses this technique to call attention to the various layers of the painting.

The following image was only allowed to be shown here during the exhibition period: Marcel Duchamp, Boîte-en-valise, 1936–1941, case with approx. 80 editions of various materials, Collection Ulla und Heiner Pietzsch, Berlin, Neue Nationalgalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin; Association Marcel Duchamp / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2024, Foto: Jens Ziehe

In the exhibition, Marcel Duchamp and his radical refections on visual art establish a connection between Kafka and contemporary art. Just as Kafka examined artistic consciousness in the story collection A Hunger Artist, Duchamp—one of the writer’s contemporaries—questioned his own role as an artist and the uniqueness of artworks. For Duchamp, ideas were more important than their execution. He expanded the concept of art by declaring his ready-mades—industrially produced everyday objects—to be artwork. He also created the female alter ego Rrose Sélavy.

As a stand-alone artwork, Boîte-en-valise (Box in a Suitcase) resembles a traveling salesman’s display case and contains miniatures of Duchamp’s works that can be carried about like a tiny museum or catalog. The replicas include works such as Fresh Widow (1920) and La Bagarre d’Austerlitz (1921) that critically refect on the painting style popular in Paris at the time. Duchamp immigrated to the United States in 1942, and Boîte-en-valise has been interpreted politically as a symbol of immigration. Kafka’s manuscripts were also transported in a suitcase— rescued from Prague by Max Brod in 1939.

The title of the catalog NOT SEEN and/or LESS SEEN refers to the act of seeing (or not seeing). For the cover Duchamp chose the same subject as in his 1927 work Porte: 11, rue Larrey. Due to spatial constraints in his Paris studio, he installed a door between two adjacent doorframes, confronting visitors with the paradox of a door that was simultaneously open and shut. The cover design continues the series of works in which Duchamp devotes himself to doors and windows—common themes in Kafka’s writings as well. In the exhibition, the catalog is presented together with the frst edition of The Metamorphosis. Kafka urged his publisher not to illustrate the cover with an insect. As an alternative, he suggested the image of a slightly opened door that would direct the viewer’s gaze to the darkness within.

The following image was only allowed to be shown here during the exhibition period: Marcel Broodthaers, La Pluie (projet pour un texte), 1969, 16 mm-film, black and white, without sound, 2 min., Collection Hoffmann, Berlin; Estate of Marcel Broodthaers, bpk / CNAC-MNAM / Hervé Véronèse, Succession Marcel Broodthaers © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2024, photo: Jewish Museum Berlin, Jens Ziehe

The poet Marcel Broodthaers decided to become an artist at the age of forty, interested in the visual representation of language and the museum as a representative institution.

Un coup de dés jamais n’abolira le hasard (A Throw of the Dice Will Never Abolish Chance) is an artist’s book created by Broodthaers to pay tribute to the 1887 modernist poem by Stéphane Mallarmé. Broodthaers believed Mallarmé was “at the source of modern art” because he liberated language from the conventions of typography and typesetting. When designing his publication, Broodthaers replaced the word “poème” (poem) on the title page with “image” and covered the lines of Mallarmé’s work with black bars. Just as Kafka transformed images into words, Broodthaers visualized language.

In the short flm La Pluie (The Rain), Broodthaers also alludes to his past as a poet. The video shows him writing in a downpour that washes away his words. It presents writing as a tragicomic endeavor.

Kafka’s Picture Riddle

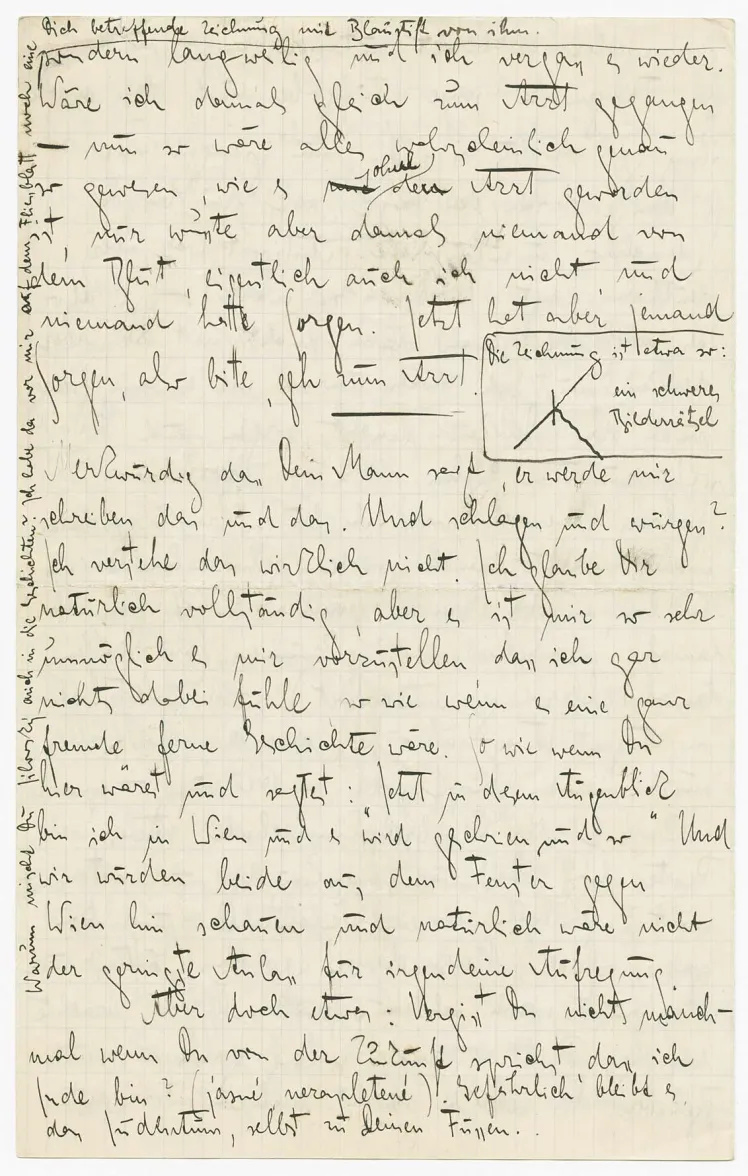

Franz Kafka and his translator into Czech, Milena Jesenská, were good friends and had a brief but intense love affair from 1919 to 1920. Find out more about it in the following letter to Milena dated July 28, 1920:

“but then nobody knew about the blood”

Franz and Milena share some intimate details. He told her about his laryngeal tuberculosis so that she would see a doctor.

Milena Jesenská (1896-1944), Czech journalist, writer, and translator, translated Kafka's texts into Czech.

Milena Jesenská, 1920; akg-images / Archiv K. Wagenbach

„your husband“

During their intense love affair, Milena was also married to the literary agent Ernst Polak.

“Don’t you sometimes forget when you talk about the future that I am Jewish?”

Milena was not Jewish. She was committed to a psychiatric ward by her father in 1917—as he did not want her to marry the Jewish literary critic Ernst Polak.

“Judaism remains dangerous, even at your feet.”

In 1939, nineteen years after this letter, Milena Jesenská joined the anti-fascist resistance against the National Socialists. She helped vulnerable people to escape from Prague.

Milena was arrested by the Gestapo in 1939 and murdered in Ravensbrück concentration camp in 1944.

“The drawing looks something like this: a difficult picture riddle”

The riddle has never been solved. Does the “K” stand for Kafka?

Milena nicknamed Kafka “Frank” because his signature was illegible.

A “difficult picture riddle”, letter to Milena Jesenská, 28.07.1920, ink on paper, 23 × 14.4 cm; DLA, D 80.15/18, Deutsches Literaturarchiv Marbach

Transcription of the letter to Milena Jesenská (excerpt)

To Milena Jesenská [Prague, July 28, 1920] Wednesday

[“...I spat out something red at the civil swimming school. It was strange and interesting, wasn’t it? I looked at it for a while and then forgot about it. And then it happened more often and when I wanted to spit I managed to make it red, it was entirely up to me. Then it was no longer interesting] but boring and I forgot about it again. If I had gone to the doctor right away—well, everything would probably have been exactly the same as it was without the doctor, but then nobody knew about the blood, actually not even me, and nobody was worried. But now someone is worried, so please go to the doctor.

Strange that your husband says he will write me this and that. And hit me and strangle me? I really don’t understand it. I believe you completely, of course, but I find it so impossible to imagine that I feel nothing about it, as if it were a completely foreign, distant story. As if you were here and said: “Right now I am in Vienna and people are shouting and stuff.” And we would both look out the window towards Vienna and of course there would be no cause for any excitement.

But one thing: don’t you sometimes forget when you talk about the future that I am Jewish? (jasná, nezapletená) [clear, uncomplicated]. Judaism remains dangerous, even at your feet.”

Access Judaism

The question of whether Kafka is a Jewish writer is best answered by the author himself. In his diary, he asks: “What do I have in common with Jews?” and immediately replies: “I have scarcely anything in common with myself.” In his texts, Kafka explores belonging and exclusion, communities and individual experiences in a way that is both ambivalent and universal. That makes him surprisingly up-to-date – people’s affiliations with a particular social group, state, or religion are neither clear-cut nor permanent. Kafka himself came from an assimilated, liberal Jewish family. He did not write explicitly about Judaism, but he learned Hebrew and was interested in Zionism. His greatest enthusiasm was for Yiddish theater, where he experienced a sense of Jewish community. His self-reflexive, ambivalent relationship with society finds its place in his art.

X

X

Franz Kafka, Self-portrait, [ca. 1911]; סימול ARC. 4* 2000 05 086, Max Brod Archive, National Library of Israel

Artworks in the Exhibition Room Access Judaism

An English translation of “of Josefine, the Singer or The Mouse-People” can be found in: Franz Kafka: A Hunger Artist and Other Stories, a new translation by Joyce Crick, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

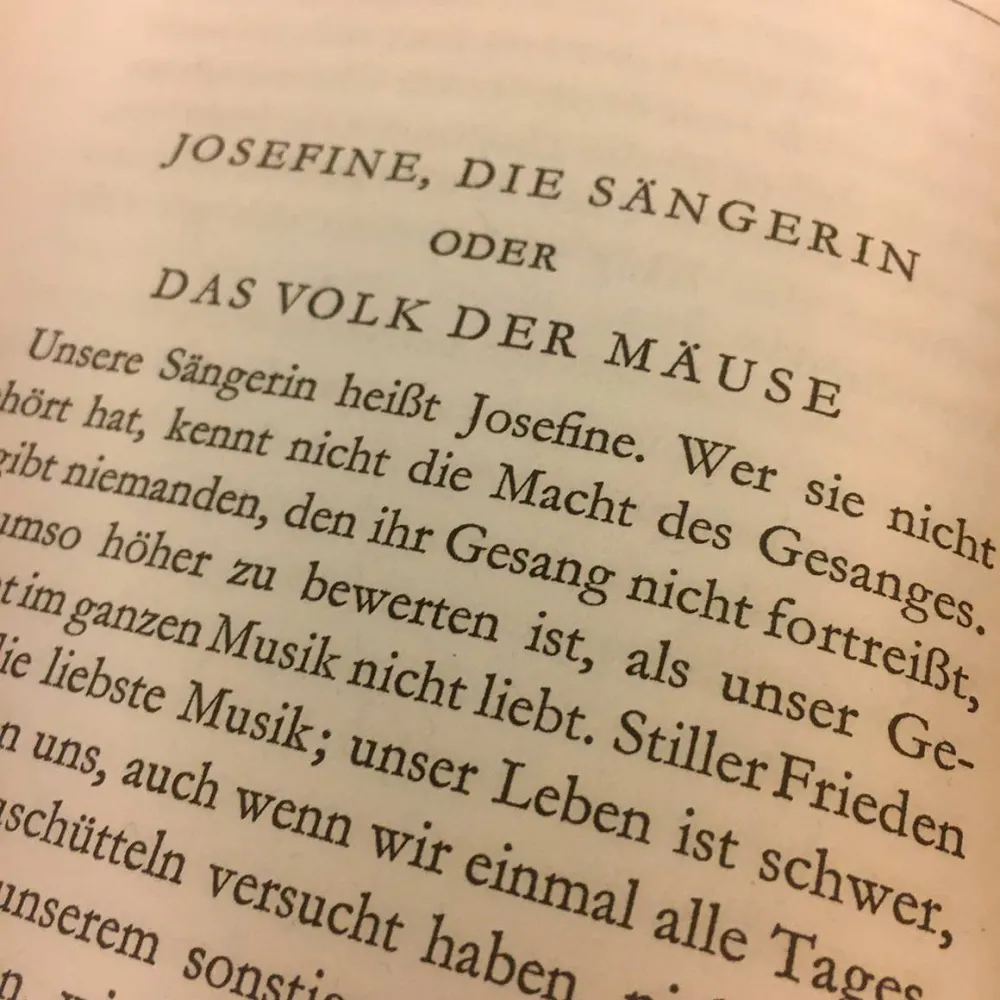

Franz Kafka, Josefine, die Sängerin oder Das Volk der Mäuse, 1924

Unsere Sängerin heißt Josefine. Wer sie nicht gehört hat, kennt nicht die Macht des Gesanges. Es gibt niemanden, den ihr Gesang nicht fortreißt, was umso höher zu bewerten ist, als unser Geschlecht im Ganzen Musik nicht liebt. Stiller Frieden ist uns die liebste Musik; unser Leben ist schwer, wir können uns, auch wenn wir einmal alle Tagessorgen abzuschütteln versucht haben, nicht mehr zu solchen, unserem sonstigen Leben so fernen Dingen erheben, wie es die Musik ist. Doch beklagen wir es nicht sehr; nicht einmal so weit kommen wir; eine gewisse praktische Schlauheit, die wir freilich auch äußerst dringend brauchen, halten wir für unseren größten Vorzug, und mit dem Lächeln dieser Schlauheit pflegen wir uns über alles hinwegzutrösten, auch wenn wir einmal – was aber nicht geschieht – das Verlangen nach dem Glück haben sollten, das von der Musik vielleicht ausgeht. Nur Josefine macht eine Ausnahme; sie liebt die Musik und weiß sie auch zu vermitteln; sie ist die Einzige; mit ihrem Hingang wird die Musik – wer weiß wie lange – aus unserem Leben verschwinden.

Ich habe oft darüber nachgedacht, wie es sich mit dieser Musik eigentlich verhält. Wir sind doch ganz unmusikalisch; wie kommt es, dass wir Josefinens Gesang verstehen oder, da Josefine unser Verständnis leugnet, wenigstens zu verstehen glauben. Die einfachste Antwort wäre, dass die Schönheit dieses Gesanges so groß ist, dass auch der stumpfste Sinn ihr nicht widerstehen kann, aber diese Antwort ist nicht befriedigend. Wenn es wirklich so wäre, müsste man vor diesem Gesang zunächst und immer das Gefühl des Außerordentlichen haben, das Gefühl, aus dieser Kehle erklinge etwas, was wir nie vorher gehört haben und das zu hören wir auch gar nicht die Fähigkeit haben, etwas, was zu hören uns nur diese eine Josefine und niemand sonst befähigt. Gerade das trifft aber meiner Meinung nach nicht zu, ich fühle es nicht und habe auch bei andern nichts dergleichen bemerkt. Im vertrauten Kreis gestehen wir einander offen, dass Josefinens Gesang als Gesang nichts Außerordentliches darstellt.

Ist es denn überhaupt Gesang? Trotz unserer Unmusikalität haben wir Gesangsüberlieferungen; in den alten Zeiten unseres Volkes gab es Gesang; Sagen erzählen davon, und sogar Lieder sind erhalten, die freilich niemand mehr singen kann. Eine Ahnung dessen, was Gesang ist, haben wir also, und dieser Ahnung nun entspricht Josefinens Kunst eigentlich nicht. Ist es denn überhaupt Gesang? Ist es nicht vielleicht doch nur ein Pfeifen? Und Pfeifen allerdings kennen wir alle, es ist die eigentliche Kunstfertigkeit unseres Volkes, oder vielmehr gar keine Fertigkeit, sondern eine charakteristische Lebensäußerung. Alle pfeifen wir, aber freilich denkt niemand daran, das als Kunst auszugeben, wir pfeifen, ohne darauf zu achten, ja, ohne es zu merken, und es gibt sogar viele unter uns, die gar nicht wissen, dass das Pfeifen zu unseren Eigentümlichkeiten gehört. Wenn es also wahr wäre, dass Josefine nicht singt, sondern nur pfeift und vielleicht gar, wie es mir wenigstens scheint, über die Grenzen des üblichen Pfeifens kaum hinauskommt - ja vielleicht reicht ihre Kraft für dieses übliche Pfeifen nicht einmal ganz hin, während es ein gewöhnlicher Erdarbeiter ohne Mühe den, ganzen Tag über neben seiner Arbeit zustandebringt - wenn das alles wahr wäre, dann wäre zwar Josefinens angebliche Künstlerschaft widerlegt, aber es wäre dann erst recht das Rätsel ihrer großen Wirkung zu lösen.

Beginning of the story “Josefine, die Sängerin oder Das Volk der Mäuse,” in: Franz Kafka, Erzählungen von Tieren, Frankfurt a. M.: S. Fischer Verlag, 2024, p. 143–166.

Picture: Page of the book Franz Kafka: Ein Hungerkünstler. Vier Geschichten. Berlin: Verlag Die Schmiede, 1924

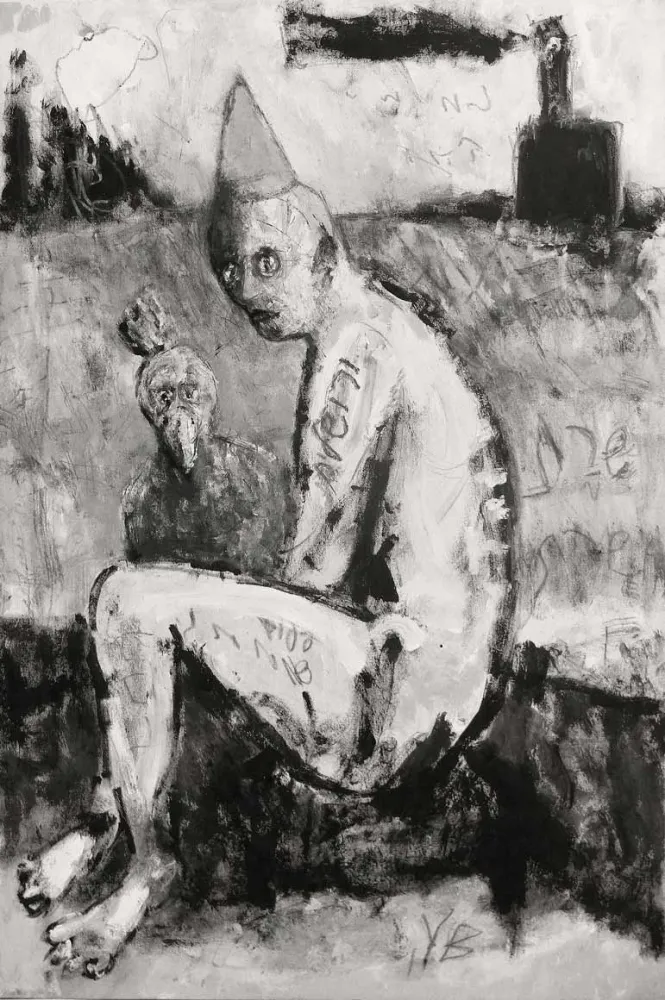

Yuval Barel, Luftmensch Antiexodus, 2020, acrylics and graphite on canvas, 60 x 90 cm; courtesy the artist

In Kafka’s day, German was spoken by a minority in Prague, which cast a critical eye on mainstream society. Yuval Barel’s language is painting. Like the drawings Kafka made in the margins of his notebooks, Barel uses his mother tongue, Hebrew, as a formal device. With his abstract imagery he attempts to rid himself of the representational elements of his art and express himself more fully through painting. His development from representational to abstract artist was triggered by his immigration to Germany. After losing his Hebrew-speaking environment, he concentrated on his primary language, painting. Luftmensch Antiexodus is a representational work. The bleak scene it depicts centers on a human fgure with a bird who is possibly the artist’s alter ego and looks tragically silly and a bit lost. By contrast, the drawings in his Conversations series are focused exercises in which Barel experiments with the language of abstract painting as a way of understanding his own state and that of his environment.

Yael Bartana, Mir Zaynen Do!, 2024, one channel video and sound installation, 11:35 min.; courtesy Capitain Petzel Gallery, Berlin; Annet Gelink Gallery, Amsterdam; Sommer Contemporary Art, Tel Aviv/Zürich; Galleria Rafaella Cortese Milan; Petzel Gallery, New York; Cecilia Hillström Gallery, Stockholm, photo: Jewish Museum Berlin, Jens Ziehe

In her work Yael Bartana explores collective memories and identities and questions the seemingly predetermined affliations that Kafka also found suspicious. In the dilapidated auditorium of the Teatro de Arte lsraelita Brasileiro, located in the cellar of the Casa do Povo in São Paulo, two groups meet in a dream-like encounter: Ilú Obá De Min, an African-Brazilian street music ensemble that draws on Candomblé culture, and the Coral Tradição, a Jewish-Brazilian choir that sings Yiddish songs. The result is a symphony of different diasporic voices. The groups have attempted to maintain their respective West African and Eastern European cultures not only in isolation but also in dialogue with one another and the majority society. Following the title Mir Zaynen Do! (We are here!), they perform, demonstrate their cohesion, and question who will take the stage in the future.

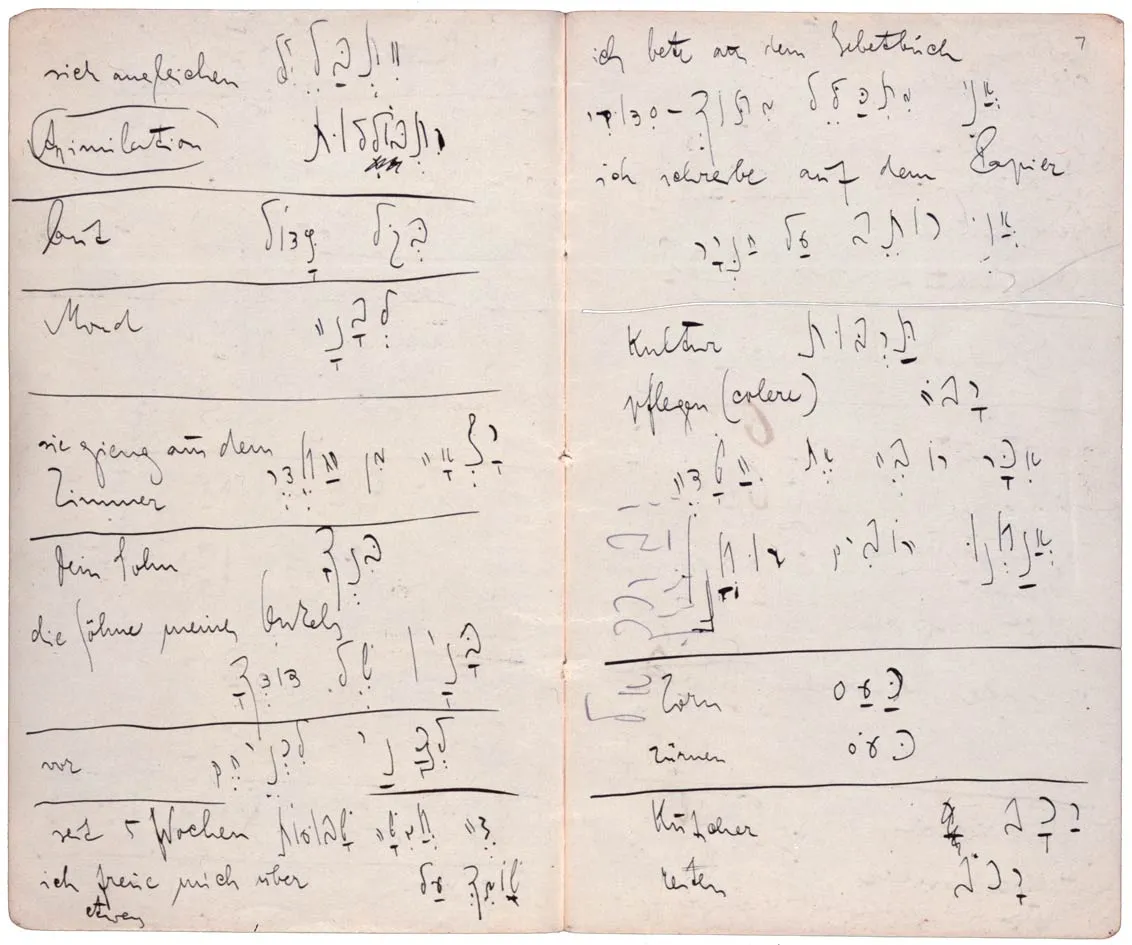

Kafka studies Hebrew

Kafka spoke German at home, among friends, and at university. Czech was increasingly spoken in the family business and at work. Kafka had also been studying Hebrew on his own since 1917. In 1922–23 Kafka attended private lessons with Puah Ben-Tovim (1903–1991). Ben-Tovim was born in Jerusalem and came to Prague to study on the recommendation of Hugo Bergmann, Kafka’s friend and director of the Hebrew National Library in Jerusalem.

There is no clear evidence as to why Kafka studied Hebrew. One of Kafka’s motivations might be that Kafka temporarily considered emigrating to British Mandate Palestine. The words in Kafka's vocabulary book provide information about what he was dealing with:

assimilation

Kafka’s family and most of his friends are assimilated, liberal, German-speaking Jews. Assimilated means culturally adapted to the Christian majority society. Liberal means reformed and not bound to the ceremonies.

culture

In his search for belonging, Kafka deals with Judaism as a culture. In 1909–11 Kafka listens to Martin Buber’s Three Speeches about Judaism in Prague with the following key messages:

- The necessity of a spiritual and cultural renewal in Judaism.

- Judaism is a culture and way of life.

- The community is central to Judaism.

Only Kafka could have made this particular selection of words, on this page for example:

assimilate, assimilation, moon, she went out of the room, your son, coachman, anger, to be angry, cultivate culture, I pray from the prayer book, I write on paper

Examples from other pages of the notebook are:

reality, midwife, bug, louse, bachelor, completion/perfection, flame

or:

that has a proof, cheek, slap, spinach, rice, pond, drink, nose, it is excluded, spinning top, mind

“I write on paper”

Kafka wrote to Milena Jesenská in mid-November 1920:

“I now spend the whole afternoon in the streets and bathe in hatred of the Jews. Prasivé plemeno (mangy race) is what I once heard the Jews being called. Isn't it only natural that one should leave a place where one is so hated (Zionism or national sentiment is not necessary)? The heroism that consists in staying is that of cockroaches, which cannot be eradicated from the bathroom after all. I've just looked out of the window: police on horseback, gendarmes ready to charge with bayonets, crowds screaming as they disperse, and up here in the window the disgusting shame of always living under protection.” (Translation by Shelley Harten)

Antisemitism as one of Kafka’s motivations for considering an emigration to British Mandate Palestine.

Franz Kafka, Hebrew vocabulary booklet, 1922–1923, ink and pencil on paper, 10.2 × 17.2 cm; MS. Kafka 30, Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford

Access Law

Kafka’s story “Before the Law” is about a man who spends his whole life demanding admission to the law. A doorkeeper prevents him from crossing the threshold intended for him. This guardian gives no reason. As a trained lawyer and a civil servant, Kafka brings questions about the law into his art: his work is concerned with meaningless constructions of bureaucratic rules, control by anonymous external forces, invasions into the private sphere, and the inaccessibility of power. In the rooms of what was once Berlin’s Court of Appeal and today is the Museum’s exhibition space, Kafka’s drawing “Guardian of the Threshold” keeps watch. Which responsibility do artists have to cast light on whatever is behind that guarded threshold?

X

X

Franz Kafka, drawing, 1901–1907, pencil on paper, 17.1 × 10.6 cm; סימול ARC. 4* 2000 05 080, Max Brod Archive, National Library Israel

Artworks in the Exhibition Room Access Law

An English translation can be found in: Franz Kafka, “Before the Law,” in: A Hunger Artist and Other Stories, a new translation by Joyce Crick, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Franz Kafka, Vor dem Gesetz, 1914

Vor dem Gesetz steht ein Türhüter. Zu diesem Türhüter kommt ein Mann vom Lande und bittet um Eintritt in das Gesetz. Aber der Türhüter sagt, dass er ihm jetzt den Eintritt nicht gewähren könne. Der Mann überlegt und fragt dann, ob er also später werde eintreten dürfen. „Es ist möglich“, sagt der Türhüter, „jetzt aber nicht.“ Da das Tor zum Gesetz offensteht wie immer und der Türhüter beiseite tritt, bückt sich der Mann, um durch das Tor in das Innere zu sehen. Als der Türhüter das merkt, lacht er und sagt: „Wenn es dich so lockt, versuche es doch, trotz meines Verbotes hineinzugehen. Merke aber: Ich bin mächtig. Und ich bin nur der unterste Türhüter. Von Saal zu Saal stehen aber Türhüter, einer mächtiger als der andere. Schon den Anblick des dritten kann nicht einmal ich mehr ertragen.“ Solche Schwierigkeiten hat der Mann vom Lande nicht erwartet; das Gesetz soll doch jedem und immer zugänglich sein, denkt er, aber als er jetzt den Türhüter in seinem Pelzmantel genauer ansieht, seine große Spitznase, den langen, dünnen, schwarzen tartarischen Bart, entschließt er sich, doch lieber zu warten, bis er die Erlaubnis zum Eintritt bekommt. Der Türhüter gibt ihm einen Schemel und lässt ihn seitwärts von der Tür sich niedersetzen. Dort sitzt er Tage und Jahre. Er macht viele Versuche, eingelassen zu werden, und ermüdet den Türhüter durch seine Bitten. Der Türhüter stellt öfters kleine Verhöre mit ihm an, fragt ihn über seine Heimat aus und nach vielem anderen, es sind aber teilnahmslose Fragen, wie sie große Herren stellen, und zum Schlusse sagt er ihm immer wieder, dass er ihn noch nicht einlassen könne. Der Mann, der sich für seine Reise mit vielem ausgerüstet hat, verwendet alles, und sei es noch so wertvoll, um den Türhüter zu bestechen. Dieser nimmt zwar alles an, aber sagt dabei: „Ich nehme es nur an, damit du nicht glaubst, etwas versäumt zu haben.“ Während der vielen Jahre beobachtet der Mann den Türhüter fast ununterbrochen. Er vergisst die anderen Türhüter, und dieser erste scheint ihm das einzige Hindernis für den Eintritt in das Gesetz. Er verflucht den unglücklichen Zufall, in den ersten Jahren rücksichtslos und laut, später, als er alt wird, brummt er nur noch vor sich hin. Er wird kindisch, und, da er in dem jahrelangen Studium des Türhüters auch die Flöhe in seinem Pelzkragen erkannt hat, bittet er auch die Flöhe, ihm zu helfen und den Türhüter umzustimmen. Schließlich wird sein Augenlicht schwach und er weiß nicht, ob es um ihn wirklich dunkler wird oder ob ihn nur seine Augen täuschen. Wohl aber erkennt er jetzt im Dunkel einen Glanz, der unverlöschlich aus der Türe des Gesetzes bricht. Nun lebt er nicht mehr lange. Vor seinem Tode sammeln sich in seinem Kopfe alle Erfahrungen der ganzen Zeit zu einer Frage, die er bisher an den Türhüter noch nicht gestellt hat. Er winkt ihm zu, da er seinen erstarrenden Körper nicht mehr aufrichten kann. Der Türhüter muss sich tief zu ihm hinunterneigen, denn der Größenunterschied hat sich sehr zuungunsten des Mannes verändert. „Was willst du denn jetzt noch wissen?“, fragt der Türhüter, „du bist unersättlich.“ „Alle streben doch nach dem Gesetz“, sagt der Mann, „wieso kommt es, dass in den vielen Jahren niemand außer mir Einlass verlangt hat?“ Der Türhüter erkennt, dass der Mann schon an seinem Ende ist, und, um sein vergehendes Gehör noch zu erreichen, brüllt er ihn an: „Hier konnte niemand sonst Einlass erhalten, denn dieser Eingang war nur für dich bestimmt. Ich gehe jetzt und schließe ihn.“

Franz Kafka, “Vor dem Gesetz,” in: Zerstreutes Hinausschauen und andere Parabeln, Frankfurt a. M.: S. Fischer Verlag, 2024, p. 59–61

Picture: Detail from the book cover of Franz Kafka: Vor dem Gesetz. Berlin: Schocken Verlag, 1934

Trevor Paglen, UNKNOWN #851111 (Unclassified object in the Orion B Molecular Complex), 2024, dye sublimation on aluminum print, 88,9 x 127 cm; courtesy the artist and Pace Gallery, photo: Jewish Museum Berlin, Jens Ziehe

The oppressive feeling of being watched plays a role in many of Kafka’s stories, but his protagonists are often unaware of who is watching them or what the consequences will be. In the digital age, surveillance is one of the most important tools used by companies and institutions. The artist Trevor Paglen works as an investigator to expose secret control mechanisms, especially those employed by the U.S. military and intelligence services, and to show how these agencies use images. What is the signifcance of the images generated by artifcial intelligence and machines? What does it mean when they take on a life of their own within power structures? These are among the questions addressed in his work.

UNKNOWN #851111: There are around 350 objects in orbit around the Earth whose origins are unknown. The U.S. Air Force publishes data on many of them, but does not track them all. The trajectories of this second category are monitored by other states and amateur photographers. For this technically sophisticated photographic series, Paglen attempted to photograph so-called unids—objects that are normally invisible to the naked eye but are potentially collecting data on all of us.

Seventeen Letters from the Deep State: In the early 2000s, Paglen investigated the CIA’s program to kidnap suspected terrorists around the world and transfer them to secret locations. As part of this mission, the CIA used private aircraft to carry the letters shown here. The documents were meant to inform customs offcials in other countries that they should not board the planes. They are all signed “Terry Hogan,” but each signature looks different. For Paglen, the letters epitomize the aesthetics of secrecy, violence, and bureaucracy.

They Took the Faces from the Accused and the Dead … : In the 1990s, before the advent of social media, mugshots of criminals were a common source of visual data to develop facial recognition software. The American National Institute of Standards, which is responsible for weights and measures, supplied researchers around the world with mugshots in the required quantities. Paglen presents a selection of photos. The white square on the faces functions as a kind of censor bar that returns to the subjects the privacy of their faces.

PALLADIUM Variation #5: With its mirrorized, faceted design, this sculpture was inspired by the fying objects built by military and intelligence agencies to fool adversarial sensor systems. Simulating UFOs, drones, and airplanes, the objects gather information about the technical capabilities of the enemy’s military. Paglen connects these attention-grabbing objects to the minimalist art of the 1960s. His focus is not the objects’ special properties, but the forms of seeing associated with them.

Roee Rosen, The Confessions of Roee Rosen, 2007–2008, video with sound, 56 min.; courtesy the artist

“It is a great torment to be governed by laws one does not know”—in his video Roee Rosen takes this statement by Kafka to the extreme. He presents three women—Roee Rosen 1, 2, and 3—making a comprehensive confession in his name. The women are foreign workers living illegally in Israel and deliver partly fctitious, partly convincing monologues in Hebrew, a language they do not speak but read from a teleprompter. They occasionally mimic the body movements and facial expressions of the real Rosen on the other side of the camera. The confessions are separated by musical interludes performed by the Roee Rosen Confessions Ensemble.

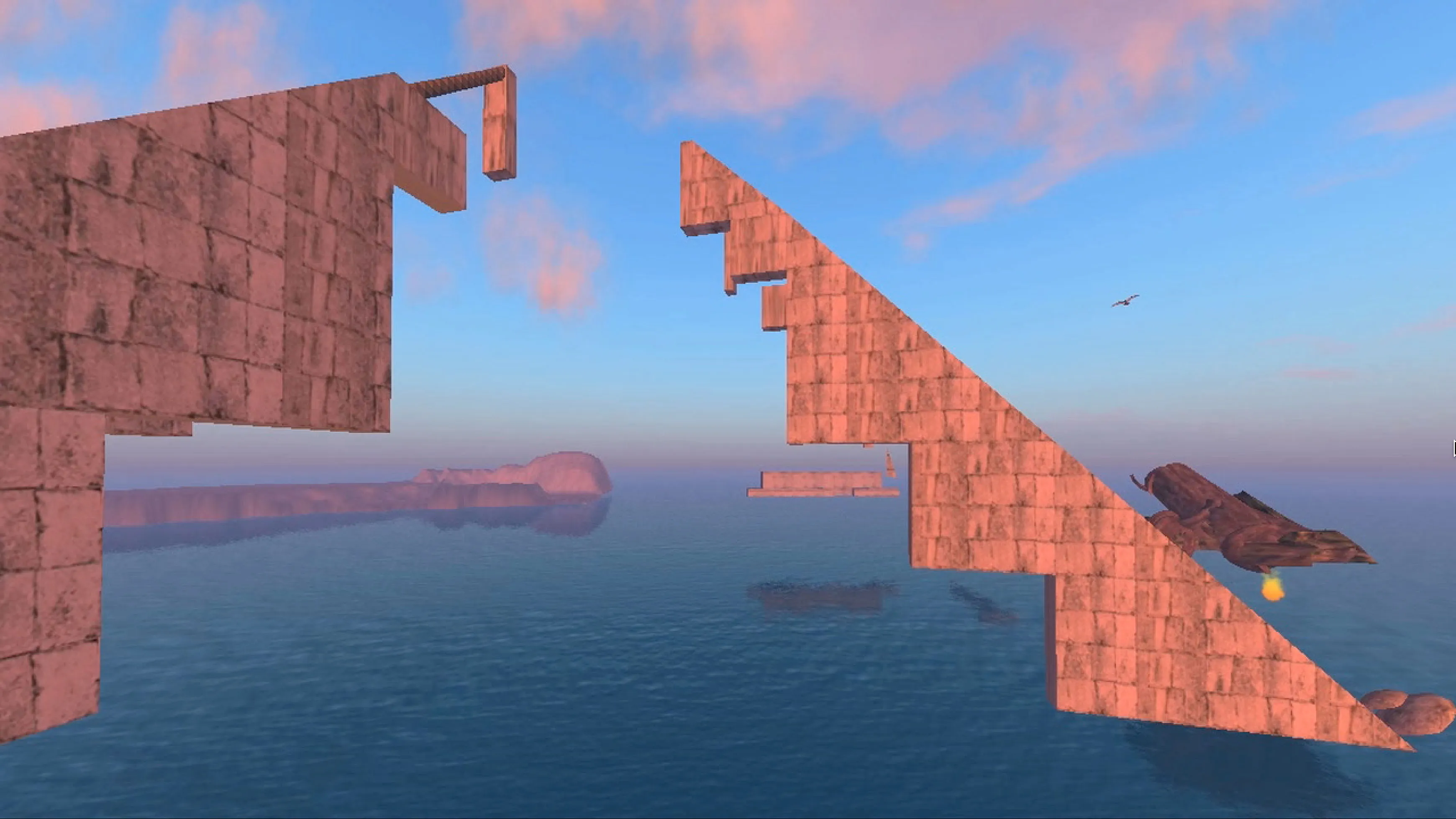

The following image was only allowed to be shown here during the exhibition period: Alona Rodeh, Altars Made of Sand, 2023, CGI 4K video with sound, 3:32 min., 3D modelling: Paulo Schmidt, Siwei Cai, houdini simulation: Paulo Schmidt, sound design: Darcy Adam; courtesy the artist © VG-Bild Kunst, Bonn 2024

Various sources describe how murderers were permitted to seek refuge in the Jerusalem Temple in biblical times. To escape blood vengeance and demand a fair trial, they would hold on to the horns of the altar where animal sacrifces took place. In Alona Rodeh’s computer-generated animation, altars of sand are washed away by the sea. The laws carved into stone prove transitory, and the hope for sanctuary and justice crumbles away. Time gnaws at everything society considers permanent.

Kafka’s Process of The Trial

Detail from the book cover of Franz Kafka: Der Prozess. Berlin: Die Schmiede, 1925.

“‘Like a dog!’ he said, it was as if the shame of it should outlive him.” (Franz Kafka, final sentence of the unfinished novel The Trial)

Franz Kafka does not manage to finish his three novels: The Trial, The Castle, and The Man Who Disappeared (America). The writing process of The Trial is reproduced here according to the findings of Kafka biographer Reiner Stach:

| May 1914 | First engagement of Franz Kafka and Felice Bauer. |

| 12 Jul 1914 | The engagement takes place in the Berlin hotel Askanischer Hof. Kafka describes the event as a tribunal in the hotel. |

| 28 Jul 1914 | Start of the First World War From 1915, Kafka is considered an “irreplaceable specialist” by the Workers’ Compensation Insurance Fund and is not called to serve at the front. |

| 11 Aug 1914 | Kafka begins to write The Trial. The first and final chapters are written first. It is probably an attempt to finish the book at all costs. However, Kafka never completes The Trial. |

| Oct 1914 | Kafka writes the story In the Penal Colony. Kafka writes the chapter on the Nature Theater of Oklahoma for the novel The Man Who Disappeared (America). |

| 30 Nov 1914 | Franz Kafka’s diary entry: “I can’t go on writing. I am at the final limit, in front of which I may have to sit for years.” |

| Oct–Dec 1914 | Kafka writes the doorkeeper legend Before the Law. The story is part of the novel The Trial, but is published separately, first published on September 7, 1915, in Selbstwehr, an independent Jewish weekly magazine, Prague. |

| Jan 1915 | Kafka’s concentration breaks off. He is no longer able to complete The Trial. |

| Jul 1916–1917 | Second engagement with Felice Bauer. |

| 1920 | Kafka writes The Problem of our Laws. The short text is about a small group of nobles who rule “us” through secret laws. |

“... it remains a vexing thing to be governed by laws one does not know.” (Franz Kafka, in The Problem of our Laws, 1920)

Access Space

For some people, globalization and the digital era open up new and unexpected spaces. Others are denied that access. The border between private and public domains begins to blur. Art, too, is no longer restricted to the traditional sites such as galleries or museums. Given that, how do we still recognize art as art? Or has art long since infiltrated everyday life? In his texts, Kafka uses motifs such as doors, gates, windows, thresholds, or buildings to give shape to feelings of hopelessness, disorientation, and unease. Many readers see themselves reflected in the narrative architecture that he creates.

X

X

Franz Kafka, drawing, [ca. 1923]; סימול ARC. 4* 2000 05 037, Max Brod Archive, National Library of Israel

Artworks in the Exhibition Room Access Space

An English translation of “First Sorrow” can be found in: Franz Kafka, A Hunger Artist and Other Stories, a new translation by Joyce Crick, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Franz Kafka, Erstes Leid, 1922

Ein Trapezkünstler – bekanntlich ist diese hoch in den Kuppeln der großen Varietébühnen ausgeübte Kunst eine der schwierigsten unter allen, Menschen erreichbaren – hatte, zuerst nur aus dem Streben nach Vervollkommnung, später auch aus tyrannisch gewordener Gewohnheit, sein Leben derart eingerichtet, dass er, solange er im gleichen Unternehmen arbeitete, Tag und Nacht auf dem Trapez blieb. Allen seinen, übrigens sehr geringen, Bedürfnissen wurde durch einander ablösende Diener entsprochen, welche unten wachten und alles, was oben benötigt wurde, in eigens konstruierten Gefäßen hinauf- und hinabzogen. Besondere Schwierigkeiten für die Umwelt ergaben sich aus dieser Lebensweise nicht; nur während der sonstigen Programm-Nummern war es ein wenig störend, dass er, wie sich nicht verbergen ließ, oben geblieben war, und dass, trotzdem er sich in solchen Zeiten meist ruhig verhielt, hier und da ein Blick aus dem Publikum zu ihm abirrte. Doch verziehen ihm dies die Direktionen, weil er ein außerordentlicher, unersetzlicher Künstler war. Auch sah man natürlich ein, dass er nicht aus Mutwillen so lebte, und eigentlich nur so sich in dauernder Übung erhalten, nur so seine Kunst in ihrer Vollkommenheit bewahren konnte.

Beginning of the story “Erstes Leid,” in: Franz Kafka, Zerstreutes Hinausschauen und andere Parabeln, Frankfurt a. M.: S. Fischer Verlag, 2024, p. 95–99

Picture: Page of the book Franz Kafka: Ein Hungerkünstler. Vier Geschichten. Berlin: Verlag Die Schmiede, 1924

Guy Ben Ner, House Hold, 2001, Video, 22:52 min.; Courtesy the artist and Sommer Contemporary Art Tel-Aviv/Zürich

You’re in a predicament and see no way out, although any onlooker can give you the solution—this is the scenario Guy Ben Ner presents in this video. The artist is trapped behind the bars of a child’s bed and turns to increasingly grotesque measures for survival. The work is typical of Ben Ner’s low and no-budget productions, which radically incorporate his private environment into his art.

Cory Arcangel, Totally Fucked, 2003, handmade hacked Super Mario Bros. cartridge, Nintendo NES video game system, artist software; courtesy the artist

This early work by Cory Arcangel shows an endless loop of Mario, the video game character, stuck on a block in a sea of blue pixels. Arcangel created the animation by hacking a Super Mario Bros. cartridge, released by Nintendo. The character, who usually jumps and runs across the screen, is unable to move because the game’s digital code has been altered. Frustration builds: viewers understand but cannot overcome Mario’s spatial limitations. Like a story by Kafka, the work offers Mario, who is controlled by external forces, no way out of his oppressive situation. Arcangel reveals the technology behind the hack—Totally Fucked can be downloaded as a ROM fle from his website and GitHub account.

Maria Eichhorn, Projekt Hollmannstraße, 1987/2024, Stones and other objects found on the site marked with red paint; pipes and furniture embedded in the ground, photo documentation; Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Jens Ziehe, courtesy the artist

In 1987, the young art student Maria Eichhorn began looking for a place to hold an exhibition in urban space. The district authorities in Kreuzberg, Berlin, placed a large undeveloped site at her disposal. Eichhorn needed to apply for offcial permits, but the process was characterized by openness and trust in her artistic intentions. She marked stones and other objects found on the site with red paint and placed iron pipes and furniture elements in the ground.

Today, the Libeskind building of the Jewish Museum stands on the site. The city archives contain no records of Eichhorn’s several-month project, nor are there traces on the property itself.

In the exhibition, a flmic and photographic documentation provides information on Eichhorn’s project from the 1980s. It is projected onto a concrete surface known as the Void Wall. The empty space behind the wall runs through the entire building, extending from the basement to the roof, and connects the old court of appeals, which can be seen in Eichhorn’s work, with the new building and exhibition spaces. In many of her works, Eichhorn explores the nature and history of places and institutions as well as the rules associated with them. The Hollmannstraße 1987/2024 project was developed especially for the Access Kafka exhibition and creates a link between the former property and the present-day museum by highlighting the signifcance of art in public spaces.

For facilitating the installation Projekt Hollmannstraße 1987/2024 by Maria Eichhorn thanks to FREUNDE DES JMB.

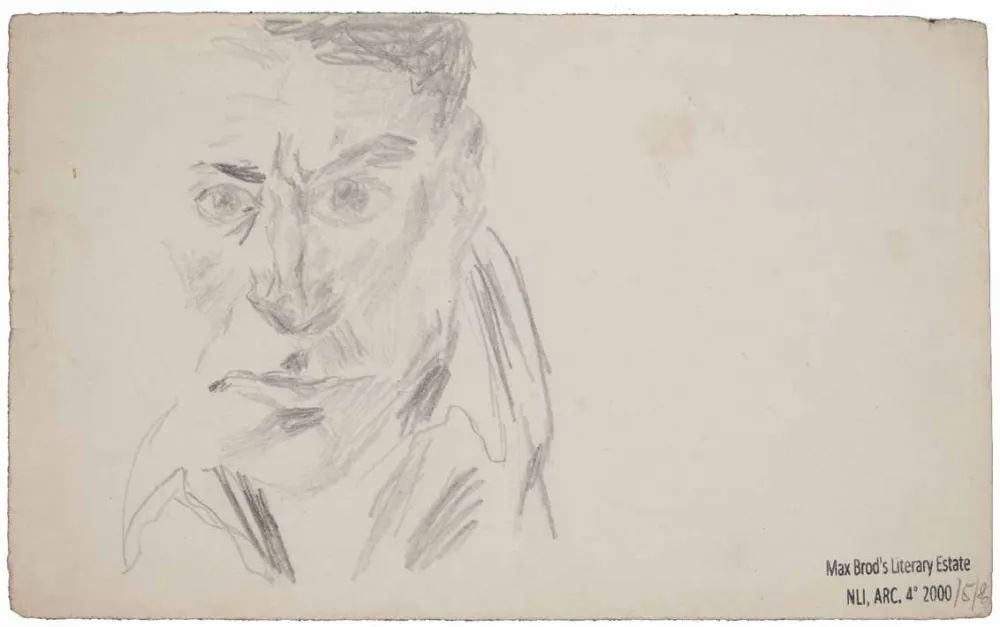

Mary Flanagan, [borders: chichen itza], 2010, video still; courtesy the artist

In Kafka’s unfnished novel The Castle, the land surveyor K. fails to gain access to the center of power in the village. The video by Mary Flanagan documents a series of walks in digital space, where the landscapes seem endless. Flanagan visits a number of publicly accessible virtual reproductions of cultural heritage sites. These include the Mayan city of Chichén Itzá in Mexico, Glengarry Castle in Scotland, the fortress of La Rocca in Italy, and the Great Wall of China. As the player in a computer game, Flanagan wanders along the virtual borders without feeling any desire to enter the actual sites. Her walks raise questions that spill over into analog space. Who has access to culture? Who determines its borders? To what extent are people trapped in their own cultural spheres?

The following image was only allowed to be shown here during the exhibition period: Gregor Schneider, u 24, FLUR, Rheydt 1989–1993, wall in front of a wall, plaster boards on a wooden construction, light yellow, 1 door (332 x 335 cm (W x H), S 10 cm), HAUS u r, Rheydt, Germany 1985 - today & u 24, FLUR, Rheydt 1989–Venedig 2001, wall in front of a wall, plaster boards on a wooden construction, light yellow, 1 door (332 x 335 cm (W x H), S 10 cm), TOTES HAUS u r, German Pavilion, 49. Biennale Venedig, la Biennale di Venezia, Venezia, Italy 10.6.2001–4.11.2001; courtesy the artist © VG Bild-Kunst Bonn 2024

Gregor Schneider’s best-known work—his residence in Unterheydener Strasse in the Rheydt district of Mönchengladbach—doesn’t look like art at all. He has worked on the site-specifc, long-term project since 1985, building rooms within rooms that hardly differ from the original spaces. He has added so many layers to the original house that his earlier “works” cannot be accessed without destroying the newer ones. When exhibiting Haus u r, he either documents or relocates the built-in rooms, essentially destroying the work in order to show it elsewhere. With his reconstructions of a small-town milieu in the Rhineland, Schneider, like Kafka, manages to make the familiar seem oppressive.

The following image was only allowed to be shown here during the exhibition period: Lina Kim, i see the sea_1A, 2022, painting on photograph printed on canvas, acrylic paint, 100 x 140 cm; courtesy the artist

Simplifed representations of eyes are superimposed on the choppy surface of the sea, and a square bracket points outside the image, seeking its counterpart there or in the next picture. It looks as if the artworks show details from the vastness of the sea—a natural, geographical border. The eyes drawn on the photographic prints resemble an undecipherable code that is meant to document or record something.

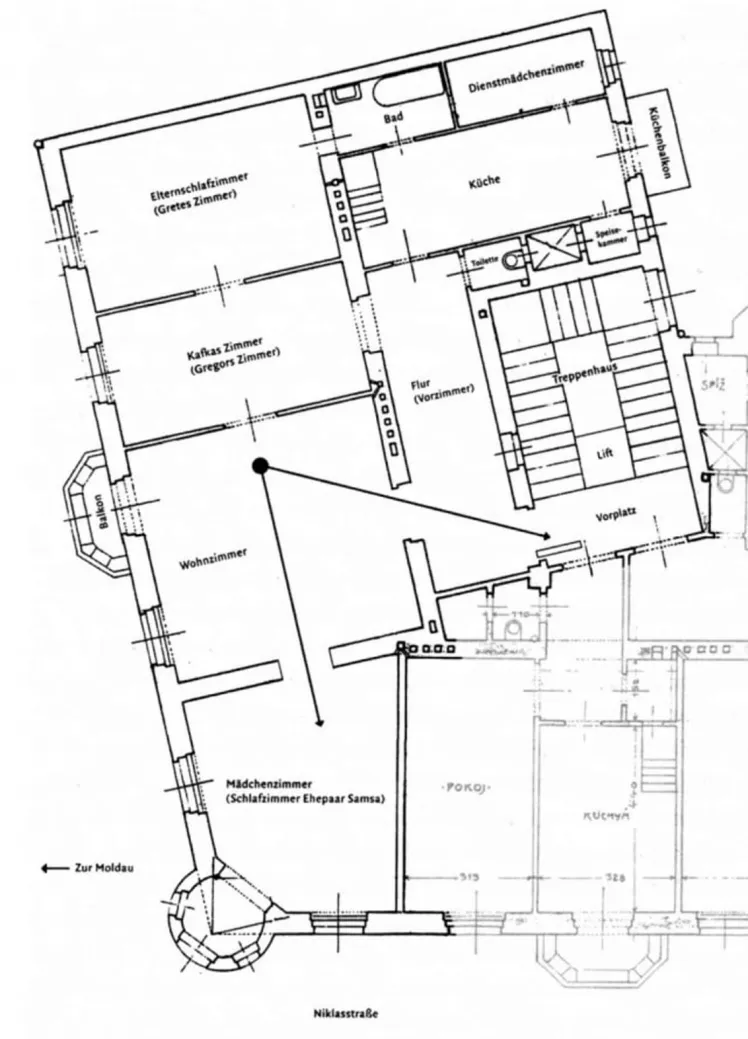

The Metamorphosis of Kafka’s Apartment

Kafka lived with his parents in Nikolasstrasse in Prague from 1907 to 1913. The apartment is on the fourth floor of the Haus zum Schiff. This is where, in November–Dezember 1912, he wrote his most famous story: The Metamorphosis.

The Kafka family’s apartment has the same floor plan as the Samsas’ apartment in The Metamorphosis.

Reality: Kafka has three sisters. The youngest, Ottilie (b. 1892), called Ottla, is his favorite.

In October 1912, Ottla encourages her brother Franz to show more commitment to the family’s asbestos factory. He would rather spend his time writing and feels betrayed, as Ottla usually stands by his side. (Letter to Max Brod, October 7/8, 1912)

Ottilie Kafka, 1910; akg-images / Archiv K. Wagenbach

Fiction: In The Metamorphosis it is in this room, that Gregor Samsa wakes up one morning as a vermin and is then increasingly rejected by his family.

Reality: Kafka is bothered by the noise of the many doors in the apartment:

“I am sitting in my room in the headquarters of the noise of the whole apartment.” Kafka hat drei Schwestern. Die jüngste, (From: Great Noise, 1912)

Fiction: First Gregor Samsa’s sister takes care of him when he becomes a vermin. Then she reveals that he is too much of a burden on the family.

Fiction: From this spot in the living room, Gregor Samsa, for the first time on his “many little legs”, looks after the Prokurist fleeing into the stairwell.

Drawing by the Kafka-expert Hartmut Binder, in: Hartmut Binder, Kafkas Verwandlung, Frankfurt a. M./Basel: Stromfeld Verlag 2004, Abb. 22

Access Body

In Kafka’s stories, bodies are animals, are transformed, are pierced by needles, hollowed out by worms, starved, executed. His own body seems to him to be weak and inadequate, even though it’s what enables him to write – an activity that for Kafka is extremely physical. He often describes art as a performance: his artist figures are performers, whether Josephine the singer, the hunger artist, or the acrobat on the trapeze. The body, as the place where regulations and exclusions are battled out, is deployed in art, especially in performance art. When they consider their sense of their own body, artists often define themselves as the last barrier between art and audience. That connects them to current debates about inclusion, body transformation, and transhumanism.

X

X

Franz Kafka, drawing on triangular paper, ca. 1906, pencil on brown paper, 10.4 × 8.3 × 7.8 cm; סימול ARC. 4* 2000 05 080, Max Brod Archive, National Library Israel

Artworks in the Exhibition Room Access Body

An English translation of “A Hunger Artist” can be found in: Franz Kafka: A Hunger Artist and Other Stories, a new translation by Joyce Crick, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Franz Kafka: Ein Hungerkünstler, 1922

In den letzten Jahrzehnten ist das Interesse an Hungerkünstlern sehr zurückgegangen. Während es sich früher gut lohnte, große derartige Vorführungen in eigener Regie zu veranstalten, ist dies heute völlig unmöglich. Es waren andere Zeiten. Damals beschäftigte sich die ganze Stadt mit dem Hungerkünstler; von Hungertag zu Hungertag stieg die Teilnahme; jeder wollte den Hungerkünstler zumindest einmal täglich sehn; an den spätern Tagen gab es Abonnenten, welche tagelang vor dem kleinen Gitterkäfig saßen; auch in der Nacht fanden Besichtigungen statt, zur Erhöhung der Wirkung bei Fackelschein; an schönen Tagen wurde der Käfig ins Freie getragen, und nun waren es besonders die Kinder, denen der Hungerkünstler gezeigt wurde.

[...]

Außer den wechselnden Zuschauern waren auch ständige, vom Publikum gewählte Wächter da, merkwürdigerweise gewöhnlich Fleischhauer, welche, immer drei gleichzeitig, die Aufgabe hatten, Tag und Nacht den Hungerkünstler zu beobachten, damit er nicht etwa auf irgendeine heimliche Weise doch Nahrung zu sich nehme. Es war das aber lediglich eine Formalität, eingeführt zur Beruhigung der Massen, denn die Eingeweihten wußten wohl, daß der Hungerkünstler während der Hungerzeit niemals, unter keinen Umständen, selbst unter Zwang nicht, auch das Geringste nur gegessen hätte; die Ehre seiner Kunst verbot dies.

[...]

Er mochte so gut hungern, als er nur konnte, und er tat es, aber nichts konnte ihn mehr retten, man ging an ihm vorüber. Versuche, jemandem die Hungerkunst zu erklären! Wer es nicht fühlt, dem kann man es nicht begreiflich machen.

[...]

„Du hungerst noch immer?“ fragte der Aufseher, „wann wirst du denn endlich aufhören?“ „Verzeiht mir alle“, flüsterte der Hungerkünstler; nur der Aufseher, der das Ohr ans Gitter hielt, verstand ihn. „Gewiß“, sagte der Aufseher und legte den Finger an die Stirn, um damit den Zustand des Hungerkünstlers dem Personal anzudeuten, „wir verzeihen dir.“ „Immerfort wollte ich, daß ihr mein Hungern bewundert“, sagte der Hungerkünstler. „Wir bewundern es auch“, sagte der Aufseher entgegenkommend. „Ihr sollt es aber nicht bewundern“, sagte der Hungerkünstler. „Nun, dann bewundern wir es also nicht“, sagte der Aufseher, „warum sollen wir es denn nicht bewundern?“ „Weil ich hungern muß, ich kann nicht anders“, sagte der Hungerkünstler. „Da sieh mal einer“, sagte der Aufseher, „warum kannst du denn nicht anders?“ „Weil ich“, sagte der Hungerkünstler, hob das Köpfchen ein wenig und sprach mit wie zum Kuß gespitzten Lippen gerade in das Ohr des Aufsehers hinein, damit nichts verloren ginge, „weil ich nicht die Speise finden konnte, die mir schmeckt. Hätte ich sie gefunden, glaube mir, ich hätte kein Aufsehen gemacht und mich vollgegessen wie du und alle.“ Das waren die letzten Worte, aber noch in seinen gebrochenen Augen war die feste, wenn auch nicht mehr stolze Überzeugung, daß er weiterhungre.

Beginning and excerpts of „Ein Hungerkünstler“, in: Franz Kafka, Die Erzählungen, Frankfurt a. M.: S. Fischer Verlag, 2024, p. 359–69

Picture: Book cover of Franz Kafka: Ein Hungerkünstler. Vier Geschichten. Berlin: Verlag Die Schmiede, 1924

Tehching Hsieh, One Year Performance 1978–1979, New York, Poster, Statement, Witness Statement, Daily Portraits, Life images; courtesy and © Tehching Hsieh, photo: Cheng Wei Kuong

In the 1970s and 1980s, Tehching Hsieh put on fve radical one-year performances that challenged him physically and mentally and had a signifcant impact on international performance art. In 1986, he implemented a “thirteen-year plan” in which he made art but agreed to not exhibit it. In the exhibition, three of his performances are presented in a documentation curated by the artist. For each performance, the documentation follows the same principle, beginning with a poster and a statement by the artist that can be read as a contract with himself and that specifes the conditions for the year. There are also statements by witnesses and excerpts from photographic and other documentary materials.

In 1978–79, Hsieh locked himself in a cage in his studio for one year. During this period of isolation, he gave up all forms of entertainment and recreation and took a picture of himself every day.

In 1981–82, Hsieh lived outdoors and did not enter interior space in Manhattan, New York. He recorded his daily wanderings on a city map. A flm clip shows police offcers arresting Hsieh and taking him into a building against his will. The judge allowed him to continue his performance, protected by the right to artistic freedom.

In 1983–84, Hsieh entered into an artistic partnership with Linda Montano. Both agreed to be tied together continuously by an 8-foot rope without touching. They recorded their conversations on tapes that were sealed and never opened.

Anne Imhof, AI Winter, 2022, video, colour, sound, 13:56 min., featuring Eliza Douglas, directed byJe an-René Étienne and Lola Raban-Oliva; courtesy the artist and Sprüth Magers, Galerie Buchholz, photo: Jewish Museum Berlin, Jens Ziehe

Like Anne Imhof's oeuvre as a whole, AI Winter focuses on performative action. It shows a shirtless fgure walking briskly along snowy paths in the ruins of Moscow’s Gorky Park. The fgure makes repetitive, machine-like gestures. The title of the flm refers both to the artist's initials and to the terminology concerned with times of low public interest in artifcial intelligence (Artifcial Intelligence Winter). What computer program is controlling the body? How autonomous are its actions? Imhof’s installation, which consists of flm, sound, and spatial elements, incorporates the visitors’ bodies in barely perceptible ways. Imhof draws viewers into an existential struggle between opposing principles: body and machine, power and powerlessness, city and nature, youth and death.

Uri Katzenstein, God/Dog Knuckle Duster, 1991, cast bronze, 8,5 x 13 x 1 cm; private collection, Berlin, photo: Roman März

The small sculpture by the multidisciplinary artist Uri Katzenstein depicts spiked brass knuckles bearing the inscriptions GOD and DOG. When the brass knuckles are worn, the letters dig into the wearer’s palm like pieces of metal type. Weapons are normally confscated by security staff at the entrance to the Jewish Museum Berlin, but this object got inside through a loophole—as a work of art. The potential for violence is palpable, as is our uncertainty about whether everyone will follow the agreed-on rules.

Lynn Hershman Leeson, Seduction of a Cyborg, 1994, video, 7 min.; courtesy the artist, Altman Siegel, San Francisco and Bridget Donahue, New York Hotwire Productions LLC, photo: Jewish Museum Berlin, Jens Ziehe

A blind woman undergoes a treatment that will enable her to see via a computer and transform her into a cyborg. She is gradually seduced by the algorithm and becomes addicted to the computer-simulated world. The technology that was meant to heal her turns out to be a disease that causes her body to waste away and ultimately kills her. Since the 1960s, Leeson has explored new technologies, cyborgs, artifcial intelligence, and questions of gender, privacy, and surveillance. Her works show how access to technology can affect the private and physical realms of people’s lives.

The following image was only allowed to be shown here during the exhibition period: Maria Lassnig, Zwei Arten zu sein (Doppelselbstporträt), 2000, and Krückenbilder (“crutch images”), oil on canvas; Maria Lassnig Foundation / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2024, photo: Jewish Museum Berlin, Jens Ziehe

Maria Lassnig and Franz Kafka certainly would have had a lot to talk about. Both had the ability to look inward and render visible what they found there. Their works establish a link between their perception of their own bodies and their struggle to represent emotion. Questions of access are also relevant. How can the body be portrayed in art or even serve as an artistic medium? Lassnig’s “crutch images” address physical mobility aids, the symbiosis of body and equipment, and, not least, aspects of social participation.

Kafka’s Body

The significance of the body is central to both Kafka’s biography and his literature. As an employee of the Workers’ Accident Insurance Institution for the Kingdom of Bohemia, he has to deal with physicality. Kafka did not hold psychoanalysis in high regard, however, he subscribed to the idea that body and mind are closely linked.

Kafka is 1.82 m tall. He has black hair under his hat.

Kafka ate preferably vegetarian and lived rather ascetically.

Kafka enjoyed eating nuts and goat’s cheese and practiced “Fletcherization,” a mastication technique named after Horace Fletcher that prescribes chewing at least thirtytwo times.

Kafka was sensitive to noise.

Neurasthenia, a nervous weakness and hypersensitivity, was all the rage in Kafka’s time.

Autumn 1917: diagnosis of his tuberculosis. Kafka to Max Brod, September 1917:

“Sometimes it seems to me that the brain and lungs have come to an agreement without my knowledge. The brain said, ‘It can't go on like this,’ and after five years the lungs offered to help.”

Regular stays in sanatoriums. Kafka died on June 3, 1924, aged almost 41.

Kafka’s mindset: truth-loving

Max Brod characterised Kafka as a strict moralist, however also as “of an enchanting wit and effervescence.”

Max Brod described Kafka’s “flashing gray eyes.”

Because Kafka suffered from insomnia, he often wrote at night.

Kafka was circumcised.

Max Brod reports that Kafka said about the story The Judgement:

“I was thinking about a strong ejaculation.”

Kafka never married, but was enganged multiple times, had girlfriends and visited brothels.

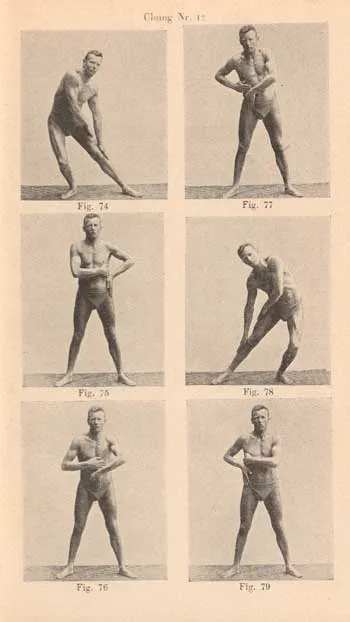

In Kafka’s time, antisemitic prejudices about Jewish masculinity as weakly, ailing, and effeminate stood against Zionist ideas of “muscular Jewry.”

Kafka was sporty: he practised swimming, rowing, walking and hiking.

Kafka “müllered” daily from around 1910: gymnastics according to the system of the Danish Jørgen Peter Müller.

J. P. Müller, Mein System. Fünfzehn Minuten täglicher Arbeit für die Gesundheit, Leipzig o.J. [ca. 1925], S. 107.

Kafka compared writing to giving birth. For him it is more important than food.

Kafka wrote at night, a lot about corporeality, e.g.

- The Metamorphosis

- A Country Doctor

- In the Penal Colony

- A Hunger Artist

Franz Kafka; akg-images / Archiv K. Wagenbach

Kafka’s Animals

Franz Kafka often includes animals as main characters in his texts. In the following picture gallery you will find some examples, illustrated for the exhibition, each with the first sentence of the story (in German):

Kafka’s Animals

Dog

Investigations of a Dog, 1922

“Wie sich mein Leben verändert hat und wie es sich doch nicht verändert hat im Grunde!”

Design: Julia Volkmar, Visual Space Agency

Cat & Mouse

A Little Fable, 1920

“‘Ach’, sagte die Maus, ‘die Welt wird enger mit jedem Tag.’”

Design: Julia Volkmar, Visual Space Agency

Monkey

A Report to an Academy, 1917

“Hohe Herren von der Akademie! Sie erweisen mir die Ehre, mich aufzufordern, der Akademie einen Bericht über mein äffisches Vorleben einzureichen.”

Design: Julia Volkmar, Visual Space Agency

Insect

The Metamorphosis, 1912

“Als Gregor Samsa eines Morgens aus unruhigen Träumen erwachte, fand er sich in seinem Bett zu einem ungeheueren Ungeziefer verwandelt.”

Design: Julia Volkmar, Visual Space Agency

Jackals

Jackals and Arabs, 1917

“Wir lagerten in der Oase.”

Design: Julia Volkmar, Visual Space Agency

Stork

The Stork in the Room, ca. 1917

“Als ich abends nachhause kam, fand ich in der Mitte des Zimmers ein grosses, ein übergrosses Ei.”

Design: Julia Volkmar, Visual Space Agency

Odradek

Odradek, or Cares of a Householder, 1917

“Die einen sagen, das Wort Odradek stamme aus dem Slawischen und sie suchen auf Grund dessen die Bildung des Wortes nachzuweisen.”

Design: Julia Volkmar, Visual Space Agency

Lamb-cat

A Crossbreed, ca. 1917

“Ich habe ein eigentümliches Tier, halb Kätzchen, halb Lamm.”

Design: Julia Volkmar, Visual Space Agency

Battle Charger

The New Advocate, 1917

“Wir haben einen neuen Advokaten, den Dr. Bucephalus. In seinem Äußern erinnert wenig an die Zeit, da er noch Streitroß Alexanders von Mazedonien war.”

Design: Julia Volkmar, Visual Space Agency

Vulture

The Vulture, 1920

“Es war ein Geier, der hackte in meine Füße.”

Design: Julia Volkmar, Visual Space Agency

Marten-like

In our Synagogue, ca. 1922

“In unserer Synagoge lebt ein Tier in der Größe etwa eines Marders.”

Design: Julia Volkmar, Visual Space Agency

Mole-like

The Burrow, 1923-24

“Ich habe den Bau eingerichtet und er scheint wohlgelungen.”

Design: Julia Volkmar, Visual Space Agency

Exhibition Information at a Glance

- When 13 Dec 2024 to 4 May 2025

- Entry Fee 10 €, reduced 4 €

- Where Old Building, level 1

Lindenstraße 9–14, 10969 Berlin

See Location on Map

Exhibition ACCESS KAFKA: Features & Programs

- Exhibition Webpage

- Current page: Access Kafka (13 Dec 2024 to 4 May 2025): Information on the exhibition chapters, artworks and documents

- Publications

- Exhibition catalog: German edition, 2024

- Exhibition catalog: English edition, 2024

- Digital Content

- Access Deferred: Essay by Vivian Liska on Kafka’s Judaism, from the exhibition catalog, 2024

- Kafka in Berlin: Berlin walk on Jewish Places to biographical stations of Franz Kafka, written by Hans-Gerd Koch

- See also

- Franz Kafka, writer: A short biography and further online content on the topic

Sponsors

X

X