“Original Voices Ensure a Diversity of Perspectives”

Interview with Lisa Albrecht about the New JMB App

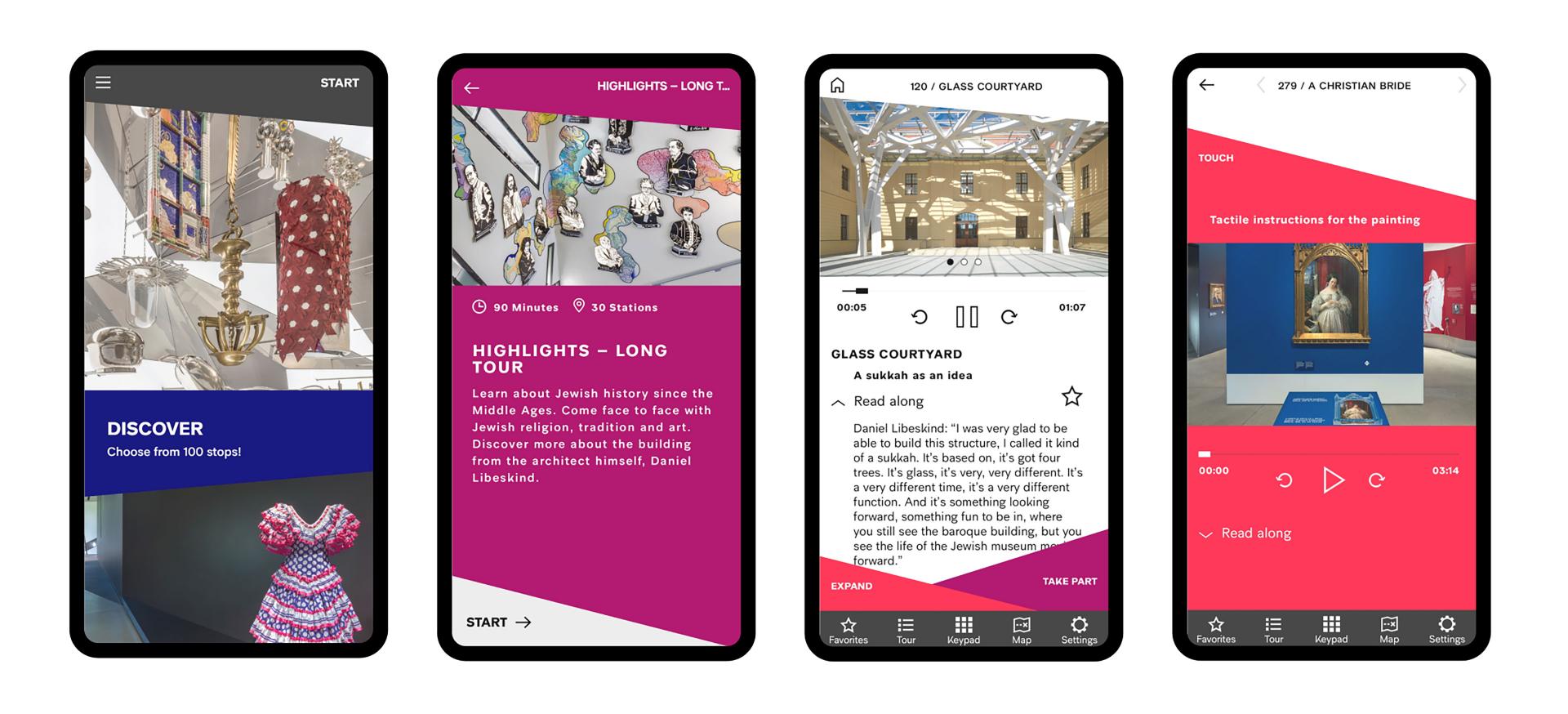

The JMB App launched with the opening of the new core exhibition in 2020. Its 2024 update comprises inclusive features; Jewish Museum Berlin, graphic: Verena Blöchl, NOUS

The picnic tables under the plane trees in the Museum Garden of the Jewish Museum Berlin are nearly empty. Lisa Albrecht is sitting where museumgoers usually stop for a break. She is the project manager of the JMB App, which is being launched in the late summer, parallel to the opening of new core exhibition. How is an audioguide being developed as an app? What methods have been used along the way to make sure the app meets users’ needs? In the sunshine amidst birdsong, Lisa talked about the working process, “design thinking” methods, and her enthusiasm for audio formats.

When the new core exhibition opens, the JMB App will replace the museum’s audioguide. Why is the guide called “JMB App”?

We’re calling our audioguide the JMB App because it’s an app for the whole museum. Besides the core exhibition, it will cover the Axes on the lower level of the Libeskind Building, the Garden, and the architecture. And at some point in the future, we would like to add content for the temporary exhibitions as well.

Why isn’t it a pure audioguide anymore?

Alongside audio, users can also read text, play games, watch videos, and view images. With the app, visitors can see their current location. That helps them find their way around the museum. In another development stage, we could also announce events or sell tickets to the museum. An app is the more suitable way to offer such diverse formats and features.

X

X

After working at the Deutsches Hygiene Museum (German Hygiene Museum) and the Cologne-based public broadcaster WDR, Lisa Albrecht is now overseeing the JMB App; Jewish Museum Berlin; photo: Immanuel Ayx

The author of an older article in the Süddeutsche Zeitung [a major daily newspaper published in Munich] cautions against “weakening the autonomy of the exhibited item” and imagines that the visitors of the future will spend the whole time staring at little screens. How can app developers complement the exhibition experience with the audioguide?

We spent a lot of time thinking about this question. The core exhibition includes many media stations, which we don’t want our app to compete with. That’s why, on the first level, we always offer audio segments. To reinforce the autonomy of visitors and exhibited artifacts, the app doesn’t start playing anything automatically. The visitors decide for themselves how they want to use the app. During the script edits, I deleted any wordings that might influence perception. I was pretty strict about that. The app is a medium that enriches – but doesn’t replace – the experience of touring the exhibition.

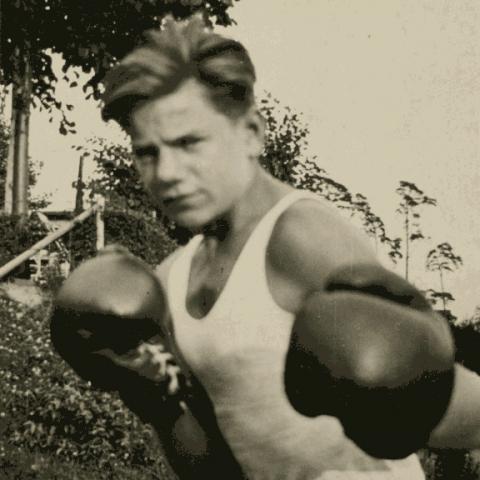

In the core exhibition, the app has various different emphases. For example, it allows visitors to explore the exhibit through the lens of life stories, including the life of Günter Loewinski.

Read along: Günter Loewinski – Boxing as self-defence

Günter Loewinski was eleven years old when his father advised him to take up a sport involving self-defence.

Günter Loewinski: “He said his motto was, ‘Being a Jew means being a fighter.’”

Self-defence? Fighting? Günther Loewinski, born in 1922, didn’t understand what his father meant at first. But he enjoyed his new hobby – boxing.

_Sound: Sounds of boxing training _

Günter Loewinski: “So we went to a boxing club … It was called JBC Berlin – Jewish Boxing Club Berlin.”

Max Buchbaum, a well-known youth trainer, took him under his wing. Soon Loewinski was winning Jewish sports club competitions nationally. At the age of 14, he won a youth boxing championship in Essen. As a reward his trainer gave him a very special trophy …

Günter Loewinski: “He said to me, ‘Here, have one of my trophies. I had your name put on it. You’re the best young fighter in Essen.’”

Loewinski trained as a tailor. Because he had a Jewish father and a non-Jewish mother, the Nazi government considered him a “Second Degree Half-breed” and he was forced to do compulsory labor. One day he was travelling on the subway in Berlin with his girlfriend Hannelore.

Günter Loewinski: “We were going up the stairs from the underground and there was a drunk Nazi paramilitary in full uniform coming towards us. He was really drunk! Hannelore was a First Degree Half-breed and didn’t have to wear her star. And anyway, he tried to molest her and I said, ‘Hannelore, see if there’s anyone on the street.’ And I gave him one under the chin and he fell right down the stairs. Then we got scared of course. We ran into the first good house entrance and stood there for two or three hours. Then I went home and my mother was very upset. My father was happy though.”

You collaborated with a very wide range of departments to produce the content. Was that challenging?

When many people are involved, it takes a lot of communication to incorporate all stakeholders and service providers. I’m glad that the JMB App is a cross-sectional project. In addition to the curators, we also collaborated with Building Management, Marketing, the Website, and two external agencies, Antenna Audio and Nous. We got to know a lot of colleagues that way.

Your team wrote scripts about the core exhibition before it was installed. How did you write about rooms that you couldn’t view yet?

The curators assembled packets of materials about the stations we selected for the JMB App. As well as views of objects, articles, and background materials, we had access to texts about objects that were already on display in the old core exhibition. We arranged the editing process so that the curators would check the scripts. But we also wrote on location when possible. That’s how the parts about the gardens and the architecture were composed.

The audio track about the Jewish Museum Berlin’s gardens includes recordings of landscape architect Hans Kollhoff and the landscape designers Cornelia Müller and Jan Wehberg.

Read along: Museum gardens – Garden behind the Old Building

Hans Kollhoff: “… there is quite a lot going on here in a small space, in contrast to baroque gardens”

Jan Wehberg: “The concept behind the _Paul Celan Courtyard_ …”

Kollhoff: “… red autumn leaves …”

Wehberg: “… to the _Paradise Garden_ …”

Cornelia Müller: “to find peace and contemplation”

Kollhoff: “the evergreen hedges”

Wehberg: “The greater whole and the overall effect are what’s important.”

There are actually two different gardens. One here, by the Old Building, and one surrounding the Libeskind part of the complex. Two museum buildings and two gardens.

The part of the gardens that you now find yourself in was established in the 1980s. The architects Hans Kolhoff and Arthur Ovaska created it for the old baroque building. At that time, the Berlin Museum occupied this building, exhibiting the city’s history. The project was part of the International Building Exhibition of 1987, along with the apartments on the longer side of the garden, to the left of where you’re standing. The Libeskind building didn’t exist yet and the courtyard was not yet enclosed in glass. Hans Kollhoff remembers:

Hans Kollhoff: “It was important for us that when you looked east from the courtyard of the Berlin Museum, there would be a rising relief feature so that you wanted to go behind it, climb the stairs and then look back at the building from above.”

Many larger baroque buildings have a garden next to them and Kollhoff and Ovaska adopted this principle. You might be familiar with other baroque gardens such as those at the Palace of Versailles. They represent mastery over nature, with geometrically trimmed hedges and trees, and fountains and other water features arranged symmetrically. Have a look around the garden now. If you walk through the circular pergola, there’s more garden to explore beyond.

Which content especially captivated you when you were working on the scripts?

The core exhibition is full of many amazing stories. I was especially fascinated by Sylvin Rubinstein’s flamenco dress.

What was so fascinating about it?

At first, the object provoked a sense of irritation. Why would a flamenco dress be on display at the Jewish Museum? On the JMB App, a short track recounts a bit about the man who wore the dress. After the disappearance of his twin sister, flamenco dancer Sylvin Rubinstein performed in dresses to commune with her. They also served as a disguise. Dressed as a woman, he carried out attacks for the Resistance. It’s a very moving story. And the nice thing is that you can easily listen to it while you’re looking at the dress in the exhibition.

In the JMB App, visitors learn more about Sylvin Rubinstein’s extraordinary life.

Read along: Sylvin Rubinstein – Dolores and Imperio

_Flamenco-Music_

Sylvin Rubinstein: “Flamenco suited us better. It’s Sephardic, it’s Moorish, and the Gypsies kept it alive. When I dance it, it’s like my sister is with me.”

Sylvin Rubinstein had an extraordinary life. Born in Russia and raised in Poland, he and his twin sister Maria were a celebrated duo in the 1930s. Under the stage names _Dolores and Imperio_, they danced their way through Europe. When the Second World War broke out, they were living in Warsaw. One year later they were confined in the Warsaw Ghetto.

Sylvin Rubinstein: “We’d only find death there.”

They escaped and, shortly afterwards, were forced to separate. Maria was supposed to catch up with the family but the plan didn’t succeed. Sylvin never saw his sister Maria again. He joined the Resistance, helping prisoners, hiding Jewish children and planning attacks. Disguised as a female singer, he threw two hand grenades into the audience of a restaurant mainly visited by SS and Gestapo members. Shortly afterwards, with forged papers, he fled to Berlin and was liberated here.

Sylvin Rubenstein never got over the loss of his sister. From then on, he took on her role when dancing. He sewed himself Flamenco dresses and performed in cabarets throughout Germany. He was able to build on the couples’ former success but this time as Dolores, alone. He never danced with a partner again.

Sylvin Rubinstein: “But God gave me Flamenco. And when I danced, he always gave me my little sister to accompany me.”

You conducted many interviews for the app. Why is that important?

We already used a lot of recorded interviews in the previous audioguide. It enriched the content and was well-received by visitors. With recordings of original voices, we ensure a diversity of perspectives and avoid a one-sided museum perspective. For example, we interviewed the architect Daniel Libeskind and the artist Yael Bartana.

Daniel Libeskind on the voids that cut through the building of the Jewish Museum Berlin; Jüdisches Museum Berlin 2017

How did it feel listening to voice actors recording the completed scripts in the studio?

It’s an incredibly amazing feeling. When I was sitting in the studio, I forgot about the drafting and editing process, which hadn’t always been easy. Having lots of people involved in drafting and editing doesn’t necessarily make the script better. So it was that much nicer to notice how well the writing flowed out loud. Besides, we have fantastic voice actors such as Heike Warmuth, Elmar Börger, Stephan Buchheim and Robert Frank. I was especially pleased that we were able to get Sandra Hüller on board for the project. She gave the scripts a personal touch during the recording sessions.

Sandra Hüller (more on Wikipedia) during the recording sessions for the JMB App; Jewish Museum Berlin; photo: Heiko Niebur

X

X

Sandra Hüller (more on Wikipedia) during the recording sessions for the JMB App; Jewish Museum Berlin; photo: Heiko Niebur

When and how did you personally discover audioguides?

When I was seventeen, I spent a summer working in Madrid as an au-pair and got bored during my free time. I used to hang out in museums all the time and listened to audioguides to improve my Spanish. Even then, I thought it was a pity that this awesome medium is often implemented so uncreatively.

Did you then choose a degree program in this area?

After graduating high school, I thought about whether to study sound at a film academy, but in the end I decided to study social sciences and linguistics and did internships in radio and some audio projects on the side. I wrote my bachelor’s thesis about an audio walk by the Canadian artist Janet Cardiff, and then for my master’s, I produced my own artistic audio walk Hör-Spuren (Audio Traces) through Ernst Thälmann Park in Berlin.

What advice would you give readers who want to become app developers?

Use and listen to audioguides with a critical ear. For example, there are some great projects by Rimini Protokoll and for a while the platform B-Tour put on a festival of walks.

The Jewish Museum Berlin has a variety of visitors. They come from all age groups and many different nationalities. How did you approach this diversity of potential users in your working process?

We applied the “persona” method from the toolkit of design thinking. In this method, you sketch out possible users, and try to cover the gamut of different museum visitors.

What would one of those “personas” look like?

For the app, one of the personas we developed was a sixteen-year-old named Bruno who comes to the museum with his parents and is bored. Another persona is Gertrud. She is seventy, is familiar with the subject matter, and interested in more in-depth knowledge. By selecting personas that are extremely different from each other, you can consult them during the production process to regularly check whether the app is meeting different users’ needs.

One particularly important audience for the museum and the app are visitors with disabilities. Can they use the app?

For the initial version of the app, we decided to focus on visitors with blindness or limited vision as a target audience. We made sure that the audio tracks would still work even if the visitors couldn’t see the objects. The app also reads all written text aloud and offers instructions for how to feel 3D tactile paintings. For visitors who are deaf or hard of hearing, we offer readable transcripts of all audio tracks. This is a minimal offering that we plan to build on in future versions.

Can you give me an example of a unique format that caters specifically to visitors with blindness or limited vision?

For several stops on our architecture tour, we interviewed the museum guide Jonas Hauer, who is blind. This way we were able to integrate his perspective of the space into the voice recordings. This is a bonus for sighted visitors as well.

For blind visitors, the Garden of Exile is one of the most intuitive places. Our museum guide Jonas Hauer, who is blind himself, explains why.

Read along: Garden of Exile “The most manageable place”

Jonas Hauer: “The Garden of Exile, yes, that was always the point where sighted and non-sighted visitors were actually separated. I know that for sighted visitors, it’s a very confusing place. For blind visitors, however, it’s very manageable. That’s because sighted people obviously orient themselves with their vision and because everything is tilted, at some point you don’t know what is actually at an angle – the columns? The floor? You? It’s very hard to orientate yourself.

For me, the structure is fantastic, because the columns are all the same size and have the same space between them. The garden has a square ground plan and it’s tilted – even tilted again on itself. The lowest point is at one of the corners, which is great for me because I know that when I want to leave, I just have to head downwards. The one thing that’s a bit disturbing is the ground. It’s very uneven. If that was smooth, it would be the perfect structure for me.

For me it was always a beautiful place. I could always relax in this garden. For sighted people it’s the opposite – the other extreme. It’s great because it illuminates exile in a completely different way. I mean I don’t really know about exile myself, but I can imagine that things like this can happen in exile. That through a new orientation, perhaps, you experience a new stability that you don’t perceive in the place you’re from or in your everyday life. For other people looking from outside, or maybe experiencing it with another sense, it’s much easier to perceive.”

I am a particularly impatient museumgoer. Does the JMB App have any tours I can complete in a short amount of time?

The exhibition encompasses more than 3,000 square meters (32,000 sq. ft.). Looking through the entire exhibition would probably take a museumgoer all day. And that’s why we developed short tours for visitors with less time to spend. You can also stroll through and just listen to the audio tracks that catch your interest.

What does kashrut mean? This audio track explains Jewish dietary laws.

Read along: Kashrut – Dietary Laws

_Jingle_

What does …

… kashrut mean?

Kashrut is a set of dietary laws which regulate the purity of food or what is kosher and can be eaten.

The kashrut is founded in the Torah. There are many rules about what is allowed to be served and what isn’t.

All fruits, vegetables and cereals are allowed. Meat and fish, however, are more complicated.

Kosher (meaning “suitable”) meat comes from ruminants with split hooves such as beef or lamb. But it is allowed under only one condition: The animal must have been slaughtered in a kosher way, i.e. with only one slash of the knife.

The meat of pigs and rabbits, for example, is not kosher. Poultry and fish do not appear randomly on the menu either. Birds cannot be scavengers and animals living in the sea must have bones and scales if they are to be eaten.

The Torah also says, “Thou shalt not cook a kid in its mother's milk.” That’s why meat and dairy products are not eaten together. Cheeseburgers and lasagnas, for example, are taboo.

The core of your identity is impacted by how seriously you take the kashrut and how strictly you follow it.

Why should visitors download the JMB App to their smartphone before they get to the museum?

There are several advantages for visitors of bringing their own devices and headphones. Most people know their way around their own devices well. Also, the app shows them tallies of the stations they’ve visited, the centuries they’ve traversed, the games they’ve played, and how many minutes they’ve listened to so far. Users also have the ability to save favorites so they can check out stations at home that they didn’t have time for in the exhibition. And the app is free of charge, by the way.

The interview was conducted by Immanuel Ayx, July 2020

Citation recommendation:

Immanuel Ayx (2020), “Original Voices Ensure a Diversity of Perspectives”. Interview with Lisa Albrecht about the New JMB App .

URL: www.jmberlin.de/en/node/7143