Entries from the Blog of the Jewish Museum Berlin

Work in Progress

Since its relaunch in 2016, our website itself has been magazine-like. For this reason, selected entries from our museum blog are gradually being transferred here. In this way, we hope to ensure that relevant, timeless entries are easier to find via the topics presented on our website. Anyone with a particular interest in texts created within the context of the blog can find all of the blog entries that have already been transferred together on this page.

Since 2017, we publish new articles, features, and online projects directly here on the website (show all online projects).

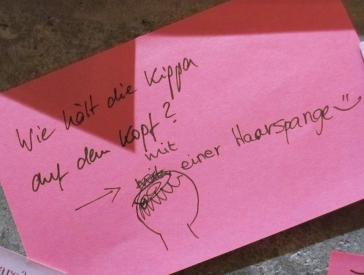

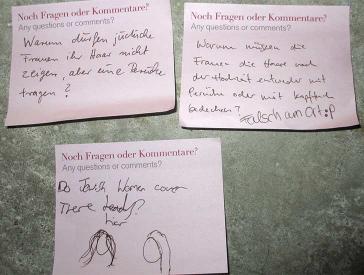

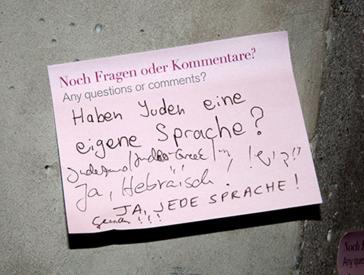

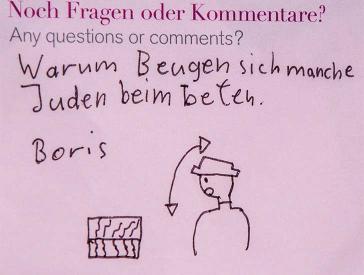

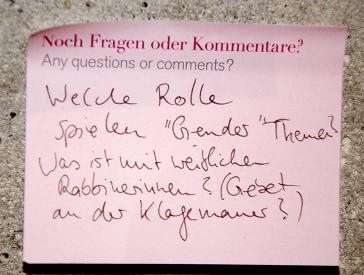

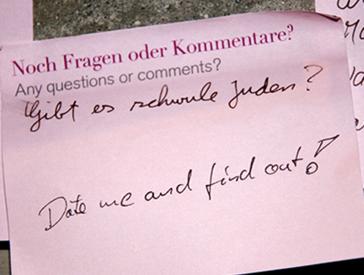

Question of the Month: Everything You Always Wanted to Know about Jews (7)

Holidays: Old Rituals, New Customs (19)

Behind the Scenes: Entries on the Exhibition “Snip it! Stances on Circumcision” (9)

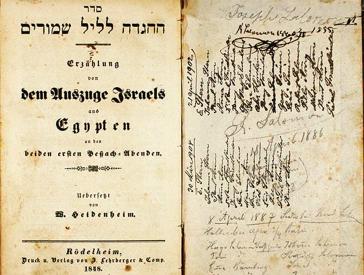

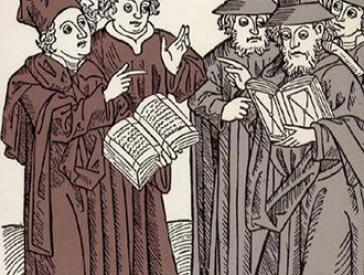

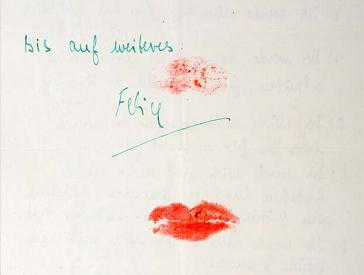

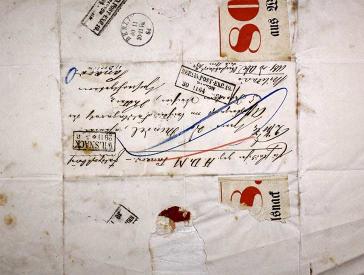

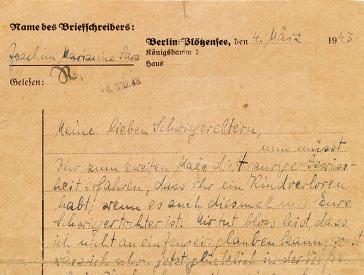

Behind the Scenes: Anecdotes and Exciting Finds while Working with our Collections (22)

Firsthand Stories: A Tour of Tour Experiences (5)

Behind the Scenes: Entries on the Exhibition “Welcome to Jerusalem” (9)

Behind the Scenes: Entries on the Exhibition “The Whole Truth” (7)

Interview Series: New German Stories (12)

Book Reviews: Contemporary Jewish Authors (2)