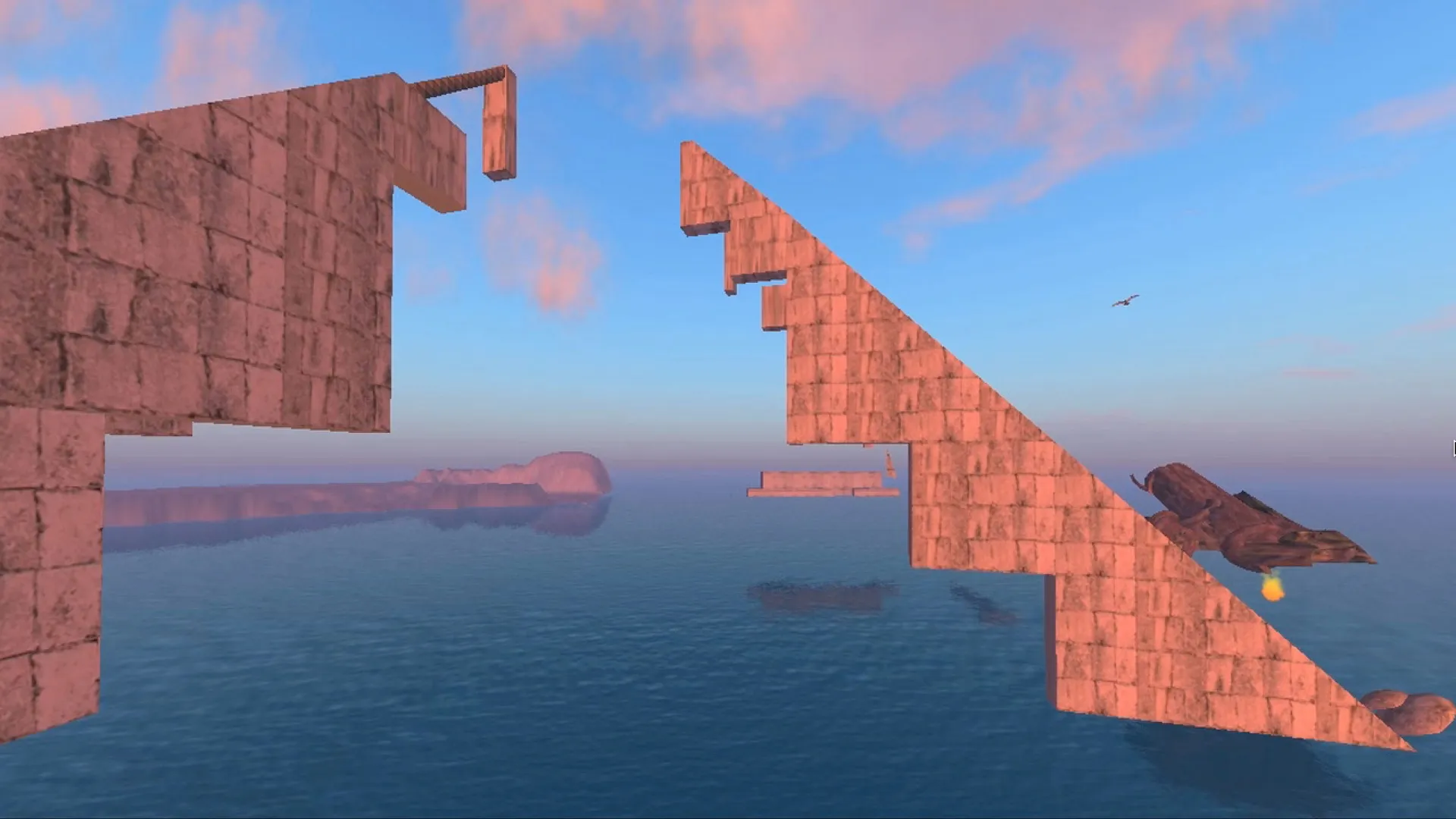

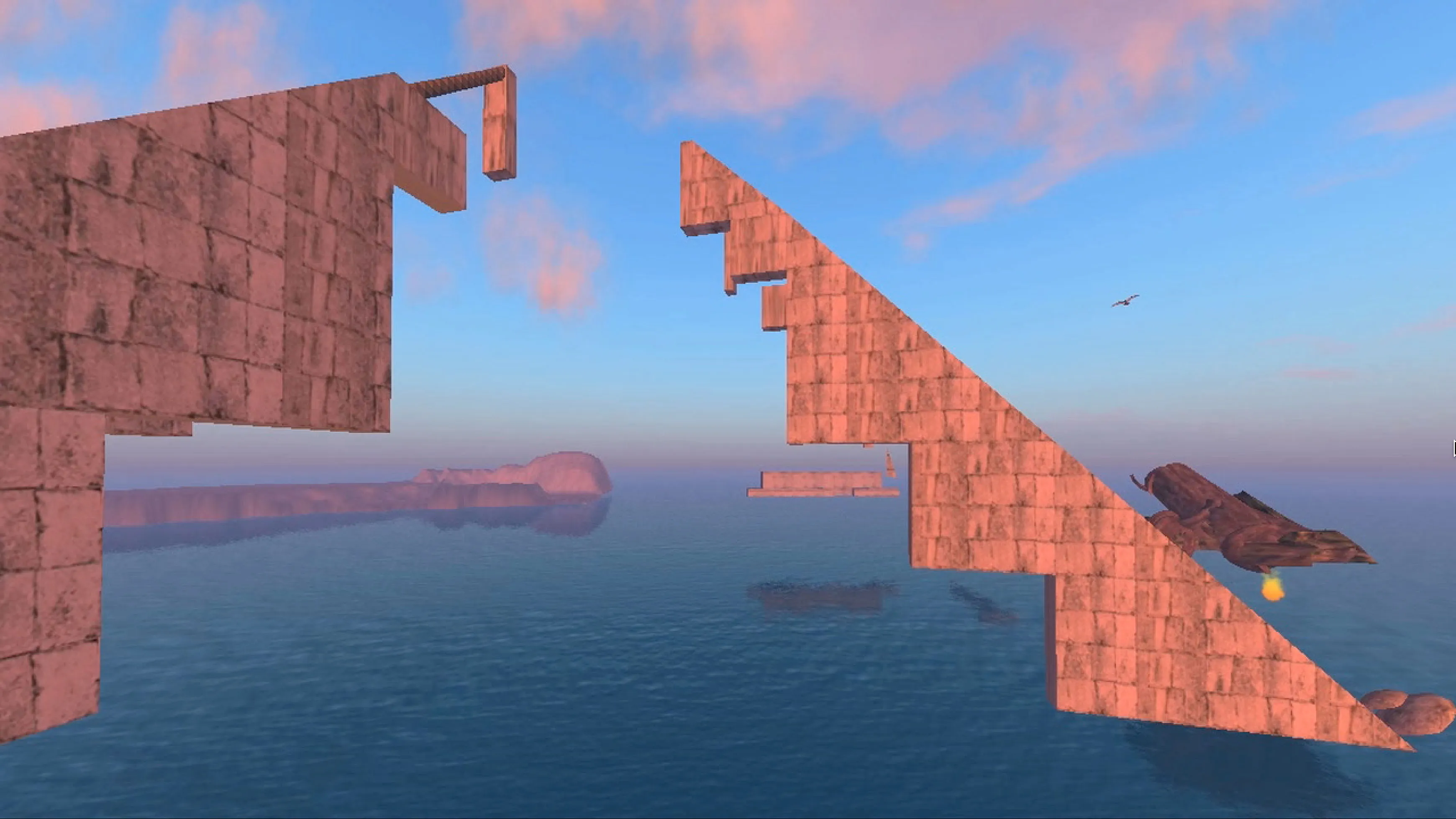

Mary Flanagan, [borders: chichen itza], 2010

Access Kafka

Exhibition

Kafka comes to Berlin! One hundred years after the death of Franz Kafka, the Jewish Museum Berlin is providing new insights into his work with its exhibition Access Kafka: manuscripts and drawings from Franz Kafka’s estate come together with contemporary art by artists such as Yael Bartana, Maria Eichhorn, Anne Imhof, Martin Kippenberger, Maria Lassnig, Trevor Paglen and Hito Steyerl. The focus is on universal and timeless questions concerning access.

Past exhibition

Where

Old Building, level 1

Lindenstraße 9–14, 10969 Berlin

In its broadest sense, the term “access” refers to the permission, freedom and ability to enter or leave a place – including an imaginary or virtual space. Questions of admission and affiliation are a recurring motif in Kafka’s literary texts. His unsettling descriptions of disorientation, surveillance and meaningless rules are relevant in a different way today than they were in Kafka’s era: the boundaries between private and public spheres are blurring in our age of widespread digitization, in which social networks, artificial intelligence and algorithms control access anonymously. These circumstances define the conditions for social participation. The contemporary artworks reflect these questions, also with reference to the role of art and artistry itself. The exhibition Access Kafka and accompanying program invite you to follow, participate in and further develop these reflections.

Artists: Cory Arcangel, Yuval Barel, Yael Bartana, Guy Ben-Ner, Marcel Broodthaers, Marcel Duchamp, Maria Eichhorn, Mary Flanagan, Ceal Floyer, Lynn Hershman Leeson, Tehching Hsieh, Anne Imhof, Fatoş İrwen, Uri Katzenstein, Lina Kim, Martin Kippenberger, Maria Lassnig, Michal Naaman, Trevor Paglen, Alona Rodeh, Roee Rosen, Gregor Schneider, Hito Steyerl

Find out more about the exhibition chapters on this page:

Exhibition Booklet

Download (PDF / 261.67 KB / in English and German / accessible)Access Denied

The refusal of access is everywhere in our society, whether economically, politically, or in private life. In his texts, Kafka – a legal scholar by training – gives tangible shape to that refusal. Josef K. is under threat of a trial without knowing why and by whom; Gregor Samsa, transformed into a kind of “vermin,” is shut out by his family; the man from the country waits in vain “Before the Law” for admission. Kafka himself nearly prevented the almost unrestricted access to his own works that we enjoy today: he instructed that all his manuscripts must be destroyed after his death. Despite the perceived accessibility of art, Kafka’s biography and texts show it is never certain when something becomes art, when somebody becomes an artist – or who decides. Is it the artists themselves? The public? Or the job market?

Franz Kafka, drawing, [ca. 1923]; סימול ARC. 4* 2000 05 037, Max Brod Archive, National Library of Israel

Artworks in the Exhibition Room Access Denied

Kafka’s Last Will

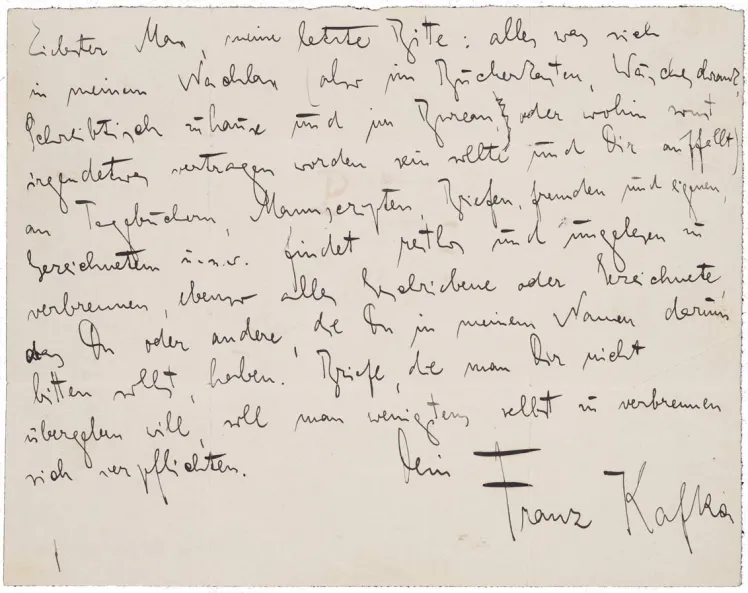

Franz Kafka died on June 3, 1924, when aged only 40. Kafka almost denied future generations access to his largely unpublished estate. Find out more from this note in his will:

Max Brod (1884-1968), author, literary and art critic, met Kafka as students in Prague in 1902 and became a very close friend. He encouraged Kafka to write and helped him publish his texts. Today he is best known as the editor of Kafka’s estate.

Max Brod, 1914, Dresden; German Literature Archive Marbach

In 1921/22, Kafka left Max Brod two testamentary notes with instructions to completely destroy his estate.

Today, the majority of Kafka’s estate is located here:

- National Library of Israel, Jerusalem

- Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford

- German Literature Archive Marbach

Max Brod ignored this instruction to burn everything unread! This is fortunate—otherwise we would only have access to previously published texts by Kafka. No Castle, no Process!

In 1939 Brod got on the very last train out of Prague as the Germans marched into the Czech Republic, in his luggage Kafka’s manuscripts e.g. the last will.

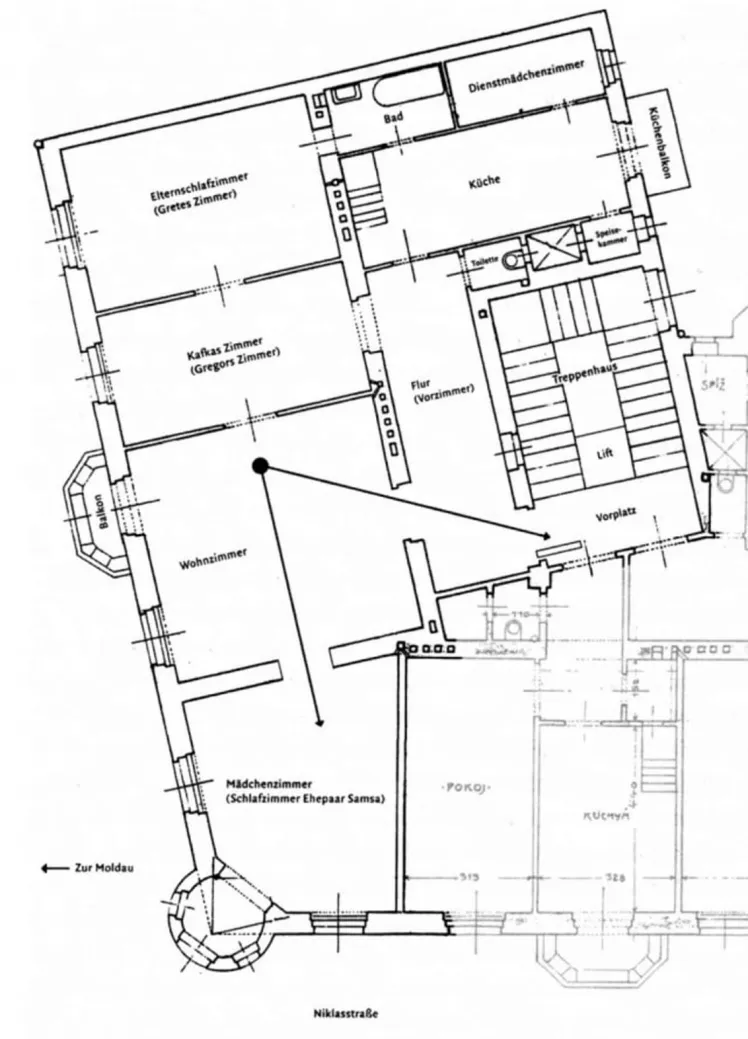

Max Brod cut out this and other drawings to illustrate the Kafka editions.

Figure from a sketch book, from about 1901–7 or later; סימול ARC. 4* 2000 05 037, Max Brod Archiv, National Library of Israel

Did Kafka really want everything to be burned? Would he then have addressed his will to Max Brod?

Testamentary note to Max Brod, from: Franz Kafka’s testaments, 1921-1922; סימול ARC. 4* 2000 05 050 Max Brod Archive, National Library of Israel

Transcription of the testamentary note to Max Brod (1921/22)

“Dearest Max, my last request: Everything I leave behind me (in my bookcase, linen cupboard, my desk both at home and in the office, or anywhere else where anything may have got to and meets your eye) in the way of diaries, manuscripts, letters (my own and others’), sketches and so on, is to be burned unread and to the last page, as well as all writings of mine or sketches which either you may have or other people, from whom you are to beg them in my name. Letters which are not handed over to you should at least be faithfully burned by those who have them.

Yours

Franz Kafka”

Benjamin Balint, Kafka’s Last Trial, The Case of a Literary Legacy, New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 2018.

Kafka’s Work

Franz Kafka was a lawyer by profession. His vocation was literature. He described both as work.

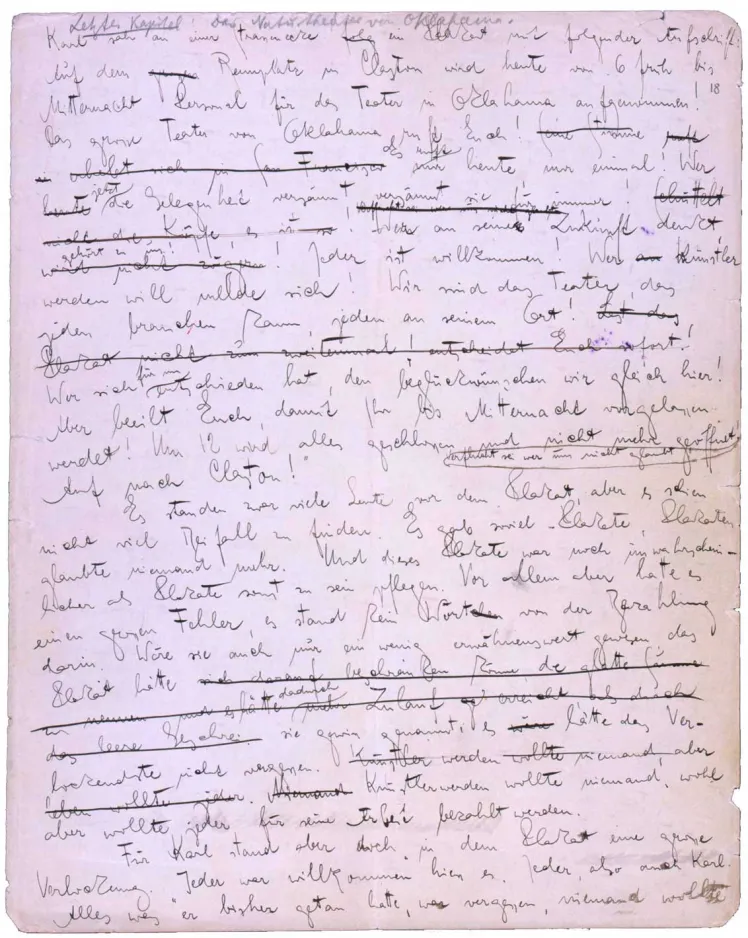

The following manuscript page from the unfinished novel The Man Who Disappeared (America), written in 1914, gives an insight into his work. It is the first page of the presumed final chapter about the protagonist Karl Rossmann's encounters with the Theater of Oklahoma.

Kafka’s novel is about the young Karl Rossmann, who emigrates to America. There he is disowned by his rich uncle and is forced to seek his fortune in the labor market.

The Nature Theater of Oklahoma is looking for artists. Karl Rossmann applies and ends up getting a job as a “technical worker” due to his lack of official documents.

handwritten addition by Max Brod:

“Last chapter: The Natural Theater of Oklahama.”

Kafka was inspired by Arthur Holitscher's travelogue America. Today and Tomorrow, 1912. Kafka copied the spelling mistake “Oklahama” from Holitscher.

Arthur Holitscher (1869–1941) was a Hungarian-Jewish author of travel books. As a socialist, he wrote about the labor market and social injustice in America.

“If you want to be an artist, come along!”

Franz Kafka raises his hand.

“No one wants to be an artist, but everyone wants to be paid for their work.” – Kafka shows solidarity with the working class.

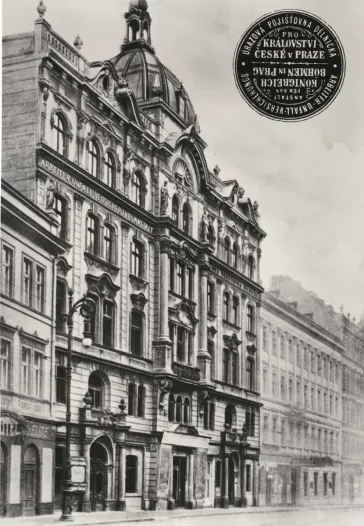

From 1908 to 1922, Kafka worked as a civil servant at the Workers’ Accident Insurance Institute in Prague.

Workers’ Accident Insurance Institute in Prague; akg-images / Archiv K. Wagenbach

First page of the presumed final chapter “The Great Theatre of Oklahama” of the unfinished novel Der Verschollene (Amerika) (The Man Who Disappeared (America)), 1914, ink and pencil on paper, 25 × 20.5 cm; MS. Kafka 42, fol. 18r, Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford

Transcription of the page above: Naturtheater von Oklahoma (in German)

Karl sah an einer Straßenecke ein Plakat mit folgender Aufschrift: „Auf dem Rennplatz in Clayton wird heute von sechs Uhr früh bis Mitternacht Personal für das Theater in Oklahama aufgenommen! Das große Theater von Oklahama ruft euch! Es ruft nur heute, nur einmal! Wer jetzt die Gelegenheit versäumt, versäumt sie für immer! Wer an seine Zukunft denkt, gehört zu uns! Jeder ist willkommen! Wer Künstler werden will, melde sich! Wir sind das Theater, das jeden brauchen kann, jeden an seinem Ort! Wer sich für uns entschieden hat, den beglückwünschen wir gleich hier! Aber beeilt euch, damit Ihr bis Mitternacht vorgelassen werdet! Um zwölf Uhr wird alles geschlossen und nicht mehr geöffnet! Verflucht sei, wer uns nicht glaubt! Auf nach Clayton!“

Es standen zwar viele Leute vor dem Plakat, aber es schien nicht viel Beifall zu finden. Es gab so viel Plakate, Plakaten glaubte niemand mehr. Und dieses Plakat war noch unwahrscheinlicher, als Plakate sonst zu sein pflegen. Vor allem aber hatte es einen großen Fehler, es stand kein Wort von der Bezahlung darin. Wäre sie auch nur ein wenig erwähnenswert gewesen, das Plakat hätte sie gewiss genannt; es hätte das Verlockendste nicht vergessen. Künstler werden wollte niemand, wohl aber wollte jeder für seine Arbeit bezahlt werden.

Für Karl stand aber doch in dem Plakat eine große Verlockung. „Jeder war willkommen“, hieß es. Jeder, also auch Karl. Alles, was er bisher getan hatte, war vergessen, niemand wollte [ihm daraus einen Vorwurf machen.]

Franz Kafka: Der Verschollene (Amerika) (The Man Who Disappeared (America)), 1914 First page of the presumed final chapter “The Great Theatre of Oklahama” of the unfinished novel

Access Word

In present-day communication forms, access is defined by symbols, slogans, codes, and emojis, and script is replaced by pictograms. Words become pictures. Kafka chooses writing and the text as his route to access the world of his imagination – a transit that demands his great concentration. His imagery often involves doors and windows, giving a visible form to experiences of exclusion and intrusion. It is rare for Kafka to describe the external appearance of his protagonists or the setting in his stories. He forbade all illustration of his works, and his own drawings are condensed like symbols. The author concentrates on the essence, leaving embellishments to his readers’ imagination.

Franz Kafka, postcard to Sophie Brod, 26.2.1911, pencil on printed cardboard, 9.3 × 14.1 cm; סימול ARC. 4* 2000 05 044, Max Brod Archive, National Library Israel

Artworks in the Exhibition Room Access Word

Kafka’s Picture Riddle

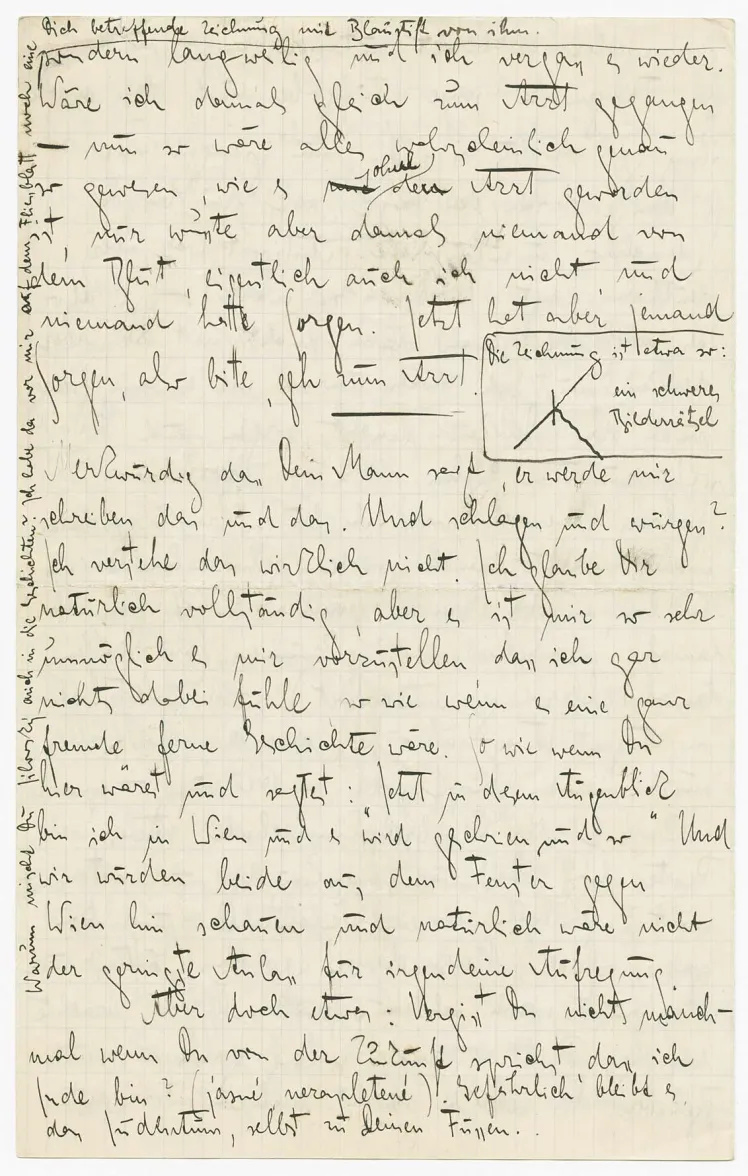

Franz Kafka and his translator into Czech, Milena Jesenská, were good friends and had a brief but intense love affair from 1919 to 1920. Find out more about it in the following letter to Milena dated July 28, 1920:

“but then nobody knew about the blood”

Franz and Milena share some intimate details. He told her about his laryngeal tuberculosis so that she would see a doctor.

Milena Jesenská (1896-1944), Czech journalist, writer, and translator, translated Kafka's texts into Czech.

Milena Jesenská, 1920; akg-images / Archiv K. Wagenbach

„your husband“

During their intense love affair, Milena was also married to the literary agent Ernst Polak.

“Don’t you sometimes forget when you talk about the future that I am Jewish?”

Milena was not Jewish. She was committed to a psychiatric ward by her father in 1917—as he did not want her to marry the Jewish literary critic Ernst Polak.

“Judaism remains dangerous, even at your feet.”

In 1939, nineteen years after this letter, Milena Jesenská joined the anti-fascist resistance against the National Socialists. She helped vulnerable people to escape from Prague.

Milena was arrested by the Gestapo in 1939 and murdered in Ravensbrück concentration camp in 1944.

“The drawing looks something like this: a difficult picture riddle”

The riddle has never been solved. Does the “K” stand for Kafka?

Milena nicknamed Kafka “Frank” because his signature was illegible.

A “difficult picture riddle”, letter to Milena Jesenská, 28.07.1920, ink on paper, 23 × 14.4 cm; DLA, D 80.15/18, Deutsches Literaturarchiv Marbach

Transcription of the letter to Milena Jesenská (excerpt)

To Milena Jesenská [Prague, July 28, 1920] Wednesday

[“...I spat out something red at the civil swimming school. It was strange and interesting, wasn’t it? I looked at it for a while and then forgot about it. And then it happened more often and when I wanted to spit I managed to make it red, it was entirely up to me. Then it was no longer interesting] but boring and I forgot about it again. If I had gone to the doctor right away—well, everything would probably have been exactly the same as it was without the doctor, but then nobody knew about the blood, actually not even me, and nobody was worried. But now someone is worried, so please go to the doctor.

Strange that your husband says he will write me this and that. And hit me and strangle me? I really don’t understand it. I believe you completely, of course, but I find it so impossible to imagine that I feel nothing about it, as if it were a completely foreign, distant story. As if you were here and said: “Right now I am in Vienna and people are shouting and stuff.” And we would both look out the window towards Vienna and of course there would be no cause for any excitement.

But one thing: don’t you sometimes forget when you talk about the future that I am Jewish? (jasná, nezapletená) [clear, uncomplicated]. Judaism remains dangerous, even at your feet.”

Access Judaism

The question of whether Kafka is a Jewish writer is best answered by the author himself. In his diary, he asks: “What do I have in common with Jews?” and immediately replies: “I have scarcely anything in common with myself.” In his texts, Kafka explores belonging and exclusion, communities and individual experiences in a way that is both ambivalent and universal. That makes him surprisingly up-to-date – people’s affiliations with a particular social group, state, or religion are neither clear-cut nor permanent. Kafka himself came from an assimilated, liberal Jewish family. He did not write explicitly about Judaism, but he learned Hebrew and was interested in Zionism. His greatest enthusiasm was for Yiddish theater, where he experienced a sense of Jewish community. His self-reflexive, ambivalent relationship with society finds its place in his art.

Franz Kafka, Self-portrait, [ca. 1911]; סימול ARC. 4* 2000 05 086, Max Brod Archive, National Library of Israel

Artworks in the Exhibition Room Access Judaism

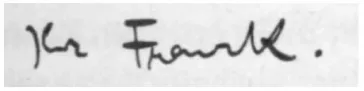

Kafka studies Hebrew

Kafka spoke German at home, among friends, and at university. Czech was increasingly spoken in the family business and at work. Kafka had also been studying Hebrew on his own since 1917. In 1922–23 Kafka attended private lessons with Puah Ben-Tovim (1903–1991). Ben-Tovim was born in Jerusalem and came to Prague to study on the recommendation of Hugo Bergmann, Kafka’s friend and director of the Hebrew National Library in Jerusalem.

There is no clear evidence as to why Kafka studied Hebrew. One of Kafka’s motivations might be that Kafka temporarily considered emigrating to British Mandate Palestine. The words in Kafka's vocabulary book provide information about what he was dealing with:

assimilation

Kafka’s family and most of his friends are assimilated, liberal, German-speaking Jews. Assimilated means culturally adapted to the Christian majority society. Liberal means reformed and not bound to the ceremonies.

culture

In his search for belonging, Kafka deals with Judaism as a culture. In 1909–11 Kafka listens to Martin Buber’s Three Speeches about Judaism in Prague with the following key messages:

- The necessity of a spiritual and cultural renewal in Judaism.

- Judaism is a culture and way of life.

- The community is central to Judaism.

Only Kafka could have made this particular selection of words, on this page for example:

assimilate, assimilation, moon, she went out of the room, your son, coachman, anger, to be angry, cultivate culture, I pray from the prayer book, I write on paper

Examples from other pages of the notebook are:

reality, midwife, bug, louse, bachelor, completion/perfection, flame

or:

that has a proof, cheek, slap, spinach, rice, pond, drink, nose, it is excluded, spinning top, mind

“I write on paper”

Kafka wrote to Milena Jesenská in mid-November 1920:

“I now spend the whole afternoon in the streets and bathe in hatred of the Jews. Prasivé plemeno (mangy race) is what I once heard the Jews being called. Isn't it only natural that one should leave a place where one is so hated (Zionism or national sentiment is not necessary)? The heroism that consists in staying is that of cockroaches, which cannot be eradicated from the bathroom after all. I've just looked out of the window: police on horseback, gendarmes ready to charge with bayonets, crowds screaming as they disperse, and up here in the window the disgusting shame of always living under protection.” (Translation by Shelley Harten)

Antisemitism as one of Kafka’s motivations for considering an emigration to British Mandate Palestine.

Franz Kafka, Hebrew vocabulary booklet, 1922–1923, ink and pencil on paper, 10.2 × 17.2 cm; MS. Kafka 30, Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford

Access Law

Kafka’s story “Before the Law” is about a man who spends his whole life demanding admission to the law. A doorkeeper prevents him from crossing the threshold intended for him. This guardian gives no reason. As a trained lawyer and a civil servant, Kafka brings questions about the law into his art: his work is concerned with meaningless constructions of bureaucratic rules, control by anonymous external forces, invasions into the private sphere, and the inaccessibility of power. In the rooms of what was once Berlin’s Court of Appeal and today is the Museum’s exhibition space, Kafka’s drawing “Guardian of the Threshold” keeps watch. Which responsibility do artists have to cast light on whatever is behind that guarded threshold?

Franz Kafka, drawing, 1901–1907, pencil on paper, 17.1 × 10.6 cm; סימול ARC. 4* 2000 05 080, Max Brod Archive, National Library Israel

Artworks in the Exhibition Room Access Law

Kafka’s Process of The Trial

Detail from the book cover of Franz Kafka: Der Prozess. Berlin: Die Schmiede, 1925.

“‘Like a dog!’ he said, it was as if the shame of it should outlive him.” (Franz Kafka, final sentence of the unfinished novel The Trial)

Franz Kafka does not manage to finish his three novels: The Trial, The Castle, and The Man Who Disappeared (America). The writing process of The Trial is reproduced here according to the findings of Kafka biographer Reiner Stach:

| May 1914 | First engagement of Franz Kafka and Felice Bauer. |

| 12 Jul 1914 | The engagement takes place in the Berlin hotel Askanischer Hof. Kafka describes the event as a tribunal in the hotel. |

| 28 Jul 1914 | Start of the First World War From 1915, Kafka is considered an “irreplaceable specialist” by the Workers’ Compensation Insurance Fund and is not called to serve at the front. |

| 11 Aug 1914 | Kafka begins to write The Trial. The first and final chapters are written first. It is probably an attempt to finish the book at all costs. However, Kafka never completes The Trial. |

| Oct 1914 | Kafka writes the story In the Penal Colony. Kafka writes the chapter on the Nature Theater of Oklahoma for the novel The Man Who Disappeared (America). |

| 30 Nov 1914 | Franz Kafka’s diary entry: “I can’t go on writing. I am at the final limit, in front of which I may have to sit for years.” |

| Oct–Dec 1914 | Kafka writes the doorkeeper legend Before the Law. The story is part of the novel The Trial, but is published separately, first published on September 7, 1915, in Selbstwehr, an independent Jewish weekly magazine, Prague. |

| Jan 1915 | Kafka’s concentration breaks off. He is no longer able to complete The Trial. |

| Jul 1916–1917 | Second engagement with Felice Bauer. |

| 1920 | Kafka writes The Problem of our Laws. The short text is about a small group of nobles who rule “us” through secret laws. |

“... it remains a vexing thing to be governed by laws one does not know.” (Franz Kafka, in The Problem of our Laws, 1920)

Access Space

For some people, globalization and the digital era open up new and unexpected spaces. Others are denied that access. The border between private and public domains begins to blur. Art, too, is no longer restricted to the traditional sites such as galleries or museums. Given that, how do we still recognize art as art? Or has art long since infiltrated everyday life? In his texts, Kafka uses motifs such as doors, gates, windows, thresholds, or buildings to give shape to feelings of hopelessness, disorientation, and unease. Many readers see themselves reflected in the narrative architecture that he creates.

Franz Kafka, drawing, [ca. 1923]; סימול ARC. 4* 2000 05 037, Max Brod Archive, National Library of Israel

Artworks in the Exhibition Room Access Space

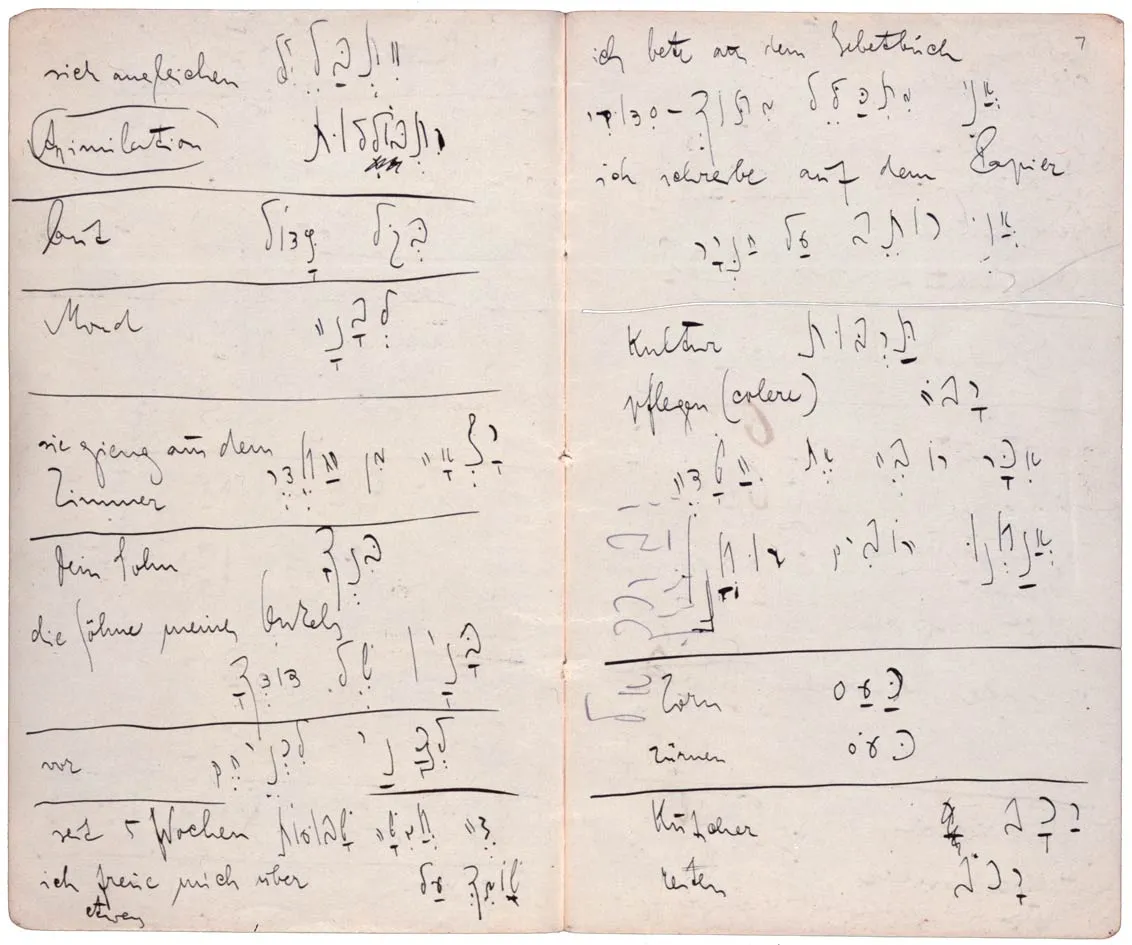

The Metamorphosis of Kafka’s Apartment

Kafka lived with his parents in Nikolasstrasse in Prague from 1907 to 1913. The apartment is on the fourth floor of the Haus zum Schiff. This is where, in November–Dezember 1912, he wrote his most famous story: The Metamorphosis.

The Kafka family’s apartment has the same floor plan as the Samsas’ apartment in The Metamorphosis.

Reality: Kafka has three sisters. The youngest, Ottilie (b. 1892), called Ottla, is his favorite.

In October 1912, Ottla encourages her brother Franz to show more commitment to the family’s asbestos factory. He would rather spend his time writing and feels betrayed, as Ottla usually stands by his side. (Letter to Max Brod, October 7/8, 1912)

Ottilie Kafka, 1910; akg-images / Archiv K. Wagenbach

Fiction: In The Metamorphosis it is in this room, that Gregor Samsa wakes up one morning as a vermin and is then increasingly rejected by his family.

Reality: Kafka is bothered by the noise of the many doors in the apartment:

“I am sitting in my room in the headquarters of the noise of the whole apartment.” Kafka hat drei Schwestern. Die jüngste, (From: Great Noise, 1912)

Fiction: First Gregor Samsa’s sister takes care of him when he becomes a vermin. Then she reveals that he is too much of a burden on the family.

Fiction: From this spot in the living room, Gregor Samsa, for the first time on his “many little legs”, looks after the Prokurist fleeing into the stairwell.

Drawing by the Kafka-expert Hartmut Binder, in: Hartmut Binder, Kafkas Verwandlung, Frankfurt a. M./Basel: Stromfeld Verlag 2004, Abb. 22

Access Body

In Kafka’s stories, bodies are animals, are transformed, are pierced by needles, hollowed out by worms, starved, executed. His own body seems to him to be weak and inadequate, even though it’s what enables him to write – an activity that for Kafka is extremely physical. He often describes art as a performance: his artist figures are performers, whether Josephine the singer, the hunger artist, or the acrobat on the trapeze. The body, as the place where regulations and exclusions are battled out, is deployed in art, especially in performance art. When they consider their sense of their own body, artists often define themselves as the last barrier between art and audience. That connects them to current debates about inclusion, body transformation, and transhumanism.

Franz Kafka, drawing on triangular paper, ca. 1906, pencil on brown paper, 10.4 × 8.3 × 7.8 cm; סימול ARC. 4* 2000 05 080, Max Brod Archive, National Library Israel

Artworks in the Exhibition Room Access Body

Kafka’s Body

The significance of the body is central to both Kafka’s biography and his literature. As an employee of the Workers’ Accident Insurance Institution for the Kingdom of Bohemia, he has to deal with physicality. Kafka did not hold psychoanalysis in high regard, however, he subscribed to the idea that body and mind are closely linked.

Kafka is 1.82 m tall. He has black hair under his hat.

Kafka ate preferably vegetarian and lived rather ascetically.

Kafka enjoyed eating nuts and goat’s cheese and practiced “Fletcherization,” a mastication technique named after Horace Fletcher that prescribes chewing at least thirtytwo times.

Kafka was sensitive to noise.

Neurasthenia, a nervous weakness and hypersensitivity, was all the rage in Kafka’s time.

Autumn 1917: diagnosis of his tuberculosis. Kafka to Max Brod, September 1917:

“Sometimes it seems to me that the brain and lungs have come to an agreement without my knowledge. The brain said, ‘It can't go on like this,’ and after five years the lungs offered to help.”

Regular stays in sanatoriums. Kafka died on June 3, 1924, aged almost 41.

Kafka’s mindset: truth-loving

Max Brod characterised Kafka as a strict moralist, however also as “of an enchanting wit and effervescence.”

Max Brod described Kafka’s “flashing gray eyes.”

Because Kafka suffered from insomnia, he often wrote at night.

Kafka was circumcised.

Max Brod reports that Kafka said about the story The Judgement:

“I was thinking about a strong ejaculation.”

Kafka never married, but was enganged multiple times, had girlfriends and visited brothels.

In Kafka’s time, antisemitic prejudices about Jewish masculinity as weakly, ailing, and effeminate stood against Zionist ideas of “muscular Jewry.”

Kafka was sporty: he practised swimming, rowing, walking and hiking.

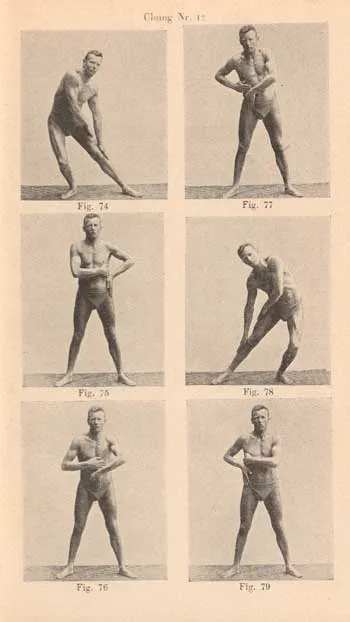

Kafka “müllered” daily from around 1910: gymnastics according to the system of the Danish Jørgen Peter Müller.

J. P. Müller, Mein System. Fünfzehn Minuten täglicher Arbeit für die Gesundheit, Leipzig o.J. [ca. 1925], S. 107.

Kafka compared writing to giving birth. For him it is more important than food.

Kafka wrote at night, a lot about corporeality, e.g.

- The Metamorphosis

- A Country Doctor

- In the Penal Colony

- A Hunger Artist

Franz Kafka; akg-images / Archiv K. Wagenbach

Kafka’s Animals

Franz Kafka often includes animals as main characters in his texts. In the following picture gallery you will find some examples, illustrated for the exhibition, each with the first sentence of the story (in German):

Kafka’s Animals

Exhibition Information at a Glance

- When 13 Dec 2024 to 4 May 2025

- Entry Fee 10 €, reduced 4 €

- Where Old Building, level 1

Lindenstraße 9–14, 10969 Berlin

See Location on Map

Exhibition ACCESS KAFKA: Features & Programs

Exhibition Webpage

Current page: Access Kafka (13 Dec 2024 to 4 May 2025): Information on the exhibition chapters, artworks and documents

Publications

- Exhibition catalog: German edition, 2024

- Exhibition catalog: English edition, 2024

Digital Content

- Access Deferred: Essay by Vivian Liska on Kafka’s Judaism, from the exhibition catalog, 2024

- Kafka in Berlin: Berlin walk on Jewish Places to biographical stations of Franz Kafka, written by Hans-Gerd Koch

See also

Franz Kafka, writer: A short biography and further online content on the topic

Sponsors