Ludwig Guttmann, Vater der Special Olympics

Ein Pionier wie Robert Koch, ein Visionär wie Coubertin

2012 wurde im englischen Stoke Mandeville eine große Bronzestatue zu Ehren eines jüdischen Arztes aus Breslau enthüllt, der trotz seiner bewegenden Geschichte, seinen Pionierleistungen und der internationalen Bedeutung seines Werkes in Deutschland nahezu unbekannt ist: Ludwig Guttmann, der Vater der Paralympischen Spiele wie auch der Special Olympics. Mehr als zweieinhalb Millionen Zuschauer werden ab dem 29. August 2012 in London den über 4.000 Athlet*innen bei den Paralympics zujubeln. In Großbritannien ist Guttmann berühmt, er wurde mit dem Orden des British Empire ausgezeichnet und die BBC widmete ihm einen Film mit dem Titel The Best of Men.

Ludwig Guttmann kam 1899 als Kind einer orthodox-jüdischen Familie im oberschlesischen Tost zur Welt. Er verbrachte seine Kindheit und Jugend in Königshütte, wo er am dortigen Krankenhaus erstmals mit Querschnittsgelähmten arbeitete. Nach seinem Medizinstudium in Breslau und Freiburg spezialisierte er sich ab 1924 auf die noch junge Disziplin der Neurochirurgie, und bald galt er als einer der führenden Ärzte auf diesem Gebiet.

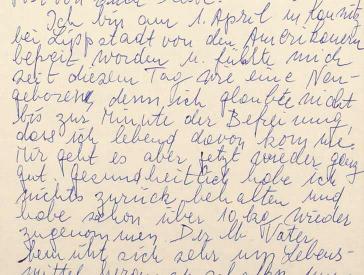

Nach der Machtübergabe an Hitler 1933 durfte er nicht mehr an einem öffentlichen Krankenhaus praktizieren. Trotz mehrerer Angebote aus Amerika verblieb er in Deutschland und ging als Facharzt an das Israelitische Krankenhaus in Breslau, später übernahm er als Direktor auch dessen Leitung. Während des Novemberpogroms 1938 wies er sein Personal nach Bekanntwerden der Gewaltexzesse an, alle Geflüchteten ohne Prüfung in das Krankenhaus aufzunehmen. Trotz einer Gestapo-Untersuchung am Krankenhaus konnte er so 60 jüdische Bürger*innen vor der Inhaftierung und Verschleppung in ein KZ bewahren.

Im Frühjahr 1939 verließ er mit seiner Familie Deutschland und emigrierte nach Großbritannien. Mit der Hilfe von Fachkollegen konnte er in Oxford seine medizinischen Forschungen zu Querschnittslähmungen fortsetzen, die er sein ganzes Berufsleben lang betrieb. 1943 bat die britische Regierung den als Koryphäe bekannten Exilanten, ein Nationales Zentrum für Rückenmarksbehandlung aufzubauen. Im folgenden Jahr wurde bereits das Stoke Mandeville Hospital unter seiner Leitung eröffnet, das vor allem Kriegsinvaliden betreute.

X

X

Marc Schuh, Rennrollstuhlfahrer (Mittelstecke), Teilnehmer der deutschen Mannschaft bei den Paralympics London 2012; Behinderten-Sportverband Berlin e.V.

Guttmann sah es als seine vorrangige Aufgabe an, den Querschnittsgelähmten nicht nur eine körperliche Rehabilitation zu ermöglichen, sondern auch ihr Selbstbewusstsein mit der dauerhaften Behinderung zu vereinen. Bis dahin war die Behandlung dieser „hoffnungslosen Fälle“ fast ausschließlich auf das Krankenbett beschränkt. Der emigrierte Arzt und Pionier nahm verschiedene Therapieansätze auf und brachte die Invaliden wortwörtlich und übertragen wieder „in Bewegung“. Als er später seinen Patienten im Rollstuhl bei einem selbst erdachten Ballspiel zusah, erkannte er die Bedeutung des Sportes auch für den eigenen und fremden Umgang mit Behinderungen: Statt als „Krüppel“ sollten sie als selbstbewusste und arbeitsfähige Mitglieder der Gesellschaft das Hospital verlassen, und die körperliche Aktivität sah Guttmann als Brücke dahin. Schon bald gehörte Sport zum festen Programm der Rehabilitation in Stoke Mandeville und ist es bis heute geblieben.

Aber Guttmann ging weiter auf seinem Weg. Als Pionier einer ganzheitlichen Therapie erkannte er die Möglichkeit öffentlicher Anerkennung und das Motivationspotenzial des Wettkampfsportes für Behinderte. Drei Jahre nach Kriegsende organisierte er zeitgleich mit den Olympischen Spielen in London erstmals die Stoke Mandeville Games, die heute als die Geburtsstunde der Paralympics gelten. In den kommenden Jahren wuchsen die Wettkampfspiele unter Guttmanns Leitung immer weiter, und 1960 erfüllte sich dessen Vision: Parallel zu den Olympischen Spielen in Rom fanden unter dem Schirm des IOC die International Stoke Mandeville Games statt. Seitdem gehören die Paralympics zu Olympia und wurden zum sportlichen Weltereignis. Nach diesem Erfolg gründete Guttmann 1961 den Britischen Behindertensportverband. Für seine Verdienste erhielt er zahlreiche internationale Ehrungen und wurde 1966 in Großbritannien zum Ritter geschlagen.

Sir Ludwig Guttmann verstarb 1980 in seiner Exilheimat. Seinen zahllosen Patienten und Paralympioniken blieb er als ihr „Poppa“ in Erinnerung, der Sportwelt als Begründer und Vater der Paralympics. Das Jewish Museum London nannte ihn in einer Ausstellung den „Coubertin der Gelähmten“.

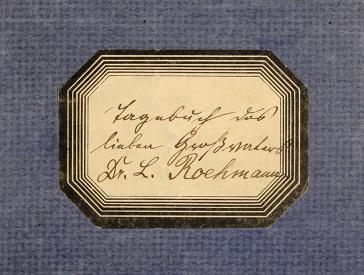

Manfred Wichmann, Archiv

Zitierempfehlung:

Manfred Wichmann (2012), Ludwig Guttmann, Vater der Special Olympics. Ein Pionier wie Robert Koch, ein Visionär wie Coubertin.

URL: www.jmberlin.de/node/9645

Blick hinter die Kulissen: Anekdoten und spannende Funde bei der Arbeit mit unseren Sammlungen (22)